I'm reminded of the movement and fluidity of sound and creation when I think of Sessa's third LP, Pequena Vertigem de Amor. I think the São Paulo musician embodies this idea in a way. In the music video for the second song off the album, "Nome de Deus," directed by Rollinos, Sessa's fluidity and movement are captured vividly. The camera switches to a multitude of views of him playing different instruments, such as the piano, bass guitar, percussion, as well as singing with a rectangular microphone in his hand. His head is always bopping, flowing with the music, and most of all when he's singing. In these shots, his body moves sometimes to the cadence of the lyrics, sometimes to the beat of different instruments, and sometimes, this movement feels ethereal or spiritual, infused with the music. This movement and fluidity are prevalent in Pequena Vertigem de Amor, making it a versatile listen that feels like recognizing all the little moments in life.

In the first song off the album, "Pequena Vertigem," the guitars strum like floating on a tube down a slow river surrounded by endless tall trees and an open blue sky, and the drums are slow, too, and patient. There are these crazy strings that trill, sometimes like birds, sometimes like a small, fervent string ensemble, in and out of the song. There is a sense of slow swelling of emotions, a fluttering. Sessa's vocals are drawn out, as if he's taking his time to feel and express. "Vale a Pena" gives some similar sensations as "Pequena Vertigem." This warmth and aura is a continuation of the movement and fluidity of the album. Even when it's slow, it's nice and comforting.

And in contrast, there are tracks like "Nome de Deus" or "Dodói," which are upbeat, containing intentional driving heartbeats that encompass evocative rhythms. And maybe the kind of rhythm is something that drives this album, as there is not nearly the same amount of nylon guitar played with melody. Instead, it serves more as a rhythm, and when the flutes, saxophone, or strings come into conversation with Sessa's voice, the layers feel different from those on previous albums. And maybe that's a little bit related to what we talked about. It makes me think of the fluidity and movement of rhythm when separated by the distinctive melody and tone of a nylon guitar. I'm not arguing that one is better, but I'm wondering what the shapes and colors feel like in contrast. Pequena Vertigem de Amor is making me want to dream, and sometimes dance, and sometimes let life come as it comes.

Jonah Evans: I can translate a little bit of the album title, something about a little bit of love. What does Pequena Vertigem de Amor mean, and what is the title about?

Sessa: It's 'A Little Love Vertigo.' It's a feeling between scare and attraction, that you feel in the stomach, when love hits. And "little" has another connotation; [the title track] was the first song I wrote after my son was born. He was really small. And those days, it's like being submarine where you don't know what's day and night. But you are also impaled with this big change and this feeling of love and dedication that comes with it.

Jonah: So, when your son was born, it was like vertigo. It was a little bit scary. But you're also just inside of it.

Sessa: Yeah, it's disorienting. A lot of things change, and you have to mature quickly, but it's moving and savage and attractive and very mundane as well. Just taking care of the diapers and the day-to-day; it was a big change for me. I've been a traveling musician for most of my life, and I didn't really have a house before I had a kid. All these things were happening, and despite time becoming a precious matter, I would try to register the ideas and the melodies, the verses, around that time. And this is a song that I was piecing together little by little in the very early days.

Jonah: So it's not as if the whole album is necessarily about you having your son in this new experience. What other topics do you explore?

Sessa: I think that the album, in an abstract way, deals with change and how things are changing around us all the time. Everything changes, and we stay in this position of a little bit of nostalgia and reluctance, attachment, and also to just embrace what's happening with this. It's informed by my early fatherhood, but also by this sense of change in a new phase of meaning, of love in this new moment. It's this ambiguity of things being so extraordinary—seeing the development of life in front of you—but also really ordinary—cleaning, making food, giving baths, putting him to sleep, and repeating.

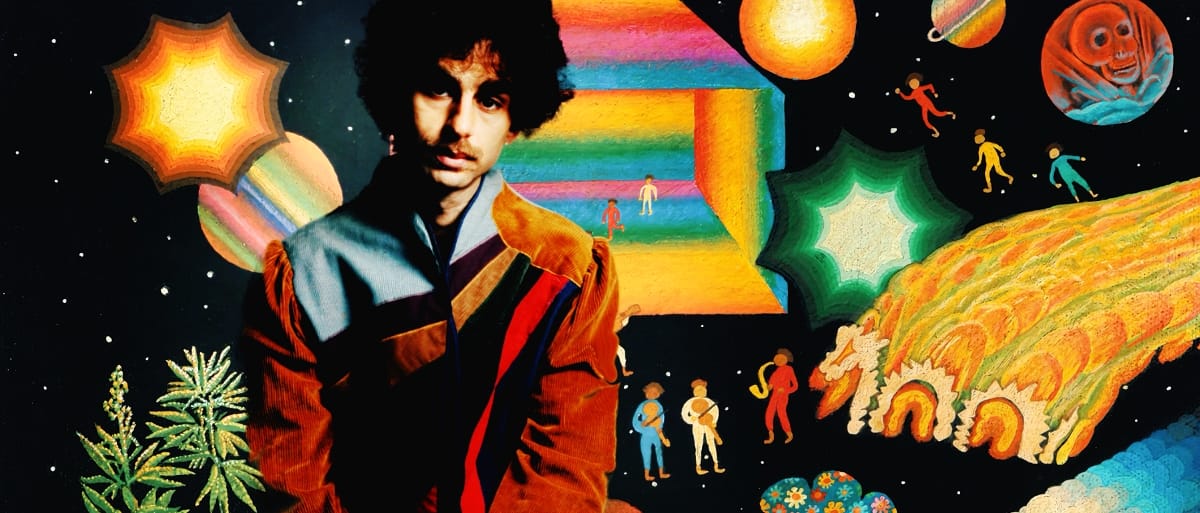

There are two registers of, like, looking down and caring for him, but the mind is also expanding, like some psychedelic trip. That's how the album cover came about, the sort of cosmic image—realizing your insignificant place in the cosmos at the same time that you're experiencing something very meaningful.

Jonah: In a couple of interviews, you talked about connecting to nature and appreciating touch and body, and just these little things. So, having another tactile thing enter your life must have been an interesting journey when thinking about change.

Sessa: Yeah, totally. And also the challenges of formulating what I was gonna talk about, right? Because there are insecurities and challenges that hover around change. I used to write about sex and skiing and relationships and partnerships between lovers, but when I managed to access the element of ambiguity, it really opened things up for me. Then I felt that I was used to writing about those things—the push and pull of attraction and the sort of love and hate of sharing your life with somebody. There's also this connection with someone that is very profound, you know?

Jonah: How do you think that translated into some of the songwriting process in this album versus previous albums?

Sessa: My first record, I had all my life to write, no one was waiting for it. I had the songs for years and years before I put them down on tape, and then between the first and the second record, I had leftovers, and all of a sudden, there was a pandemic. I had so much time to formulate and conceptualize. It was very different because, for this record, from those early days when my kid was born until I went to mastering, I spent about three years writing, recording, mixing, and mastering. So, it's just the last two and a half years of my life that are registered there. There's something cool about it, because I feel like a lot of my arrangements and production ideas were very conceptualized and strict, with very few elements—empty, minimalistic.

Some of it was just the circumstances. I was making my records pretty DIY, but part of it was like, "Okay, this is an acoustic record. It's just nylon guitar, lots of voice, and percussion. And then every now and then comes a loud free jazz band. That's my palette—no more, no less." It also has to do with the fact that after years of having equipment everywhere [in different cities and houses], I managed to get it all together because I was more stable in a place. And Biel [Basile], who plays drums and co-produces the album with me, we officially started our studio, so this stuff was all there. So there are more colors and a bit more play. There's a wider cast of musicians involved, but I still made it in chunks; it's like maybe five sessions across, a bit under two years. I didn't have a full batch of songs before I went in.

Jonah: So, you would write, and when you recorded, you would invite musicians to come decide if there should be keys or something else on the song.

Sessa: More or less, yes. There are two keyboardists on the record. One is Marcelo [Maita], who plays acoustic piano, and the other is Alex Chumak, who plays electric piano. I had a couple of songs that really needed this particular Brazilian late-night Rio club sound. They are "Nome de Deus" and "Dodói." And so somebody introduced me to Maita, who's like a local legend and played with everybody. I had these ideas about arranging the songs, but this actually just happened during the session. You start to get a sense of what the person is capable of, and you ride the wave. Those are legendary sessions in my humble life. Like, you walk out of the studio floating on the music that you created, you know? So it's more like the chicken and the egg: did the sound come from the idea, or did the idea come from hearing the sounds?

Jonah: What's it like leaving the studio with that magical feeling versus being unsure?

Sessa: Usually, in the same session, you have both. There were things that I didn't use with Maita. I know when it's right and when it's wrong. Sometimes I'm confused, and I let it sit for a bit and try pushing a bit more. And then you need some space because studio days are long, and in the end, you want to crash out.

For the more electric piano, the synths, that's Alex. He's a Belarusian musician with the band SOYUZ. They make pretty good music and have a Brazilian feel, a special fusion sound. We became pen pals, and he arranged for my previous record and for this one. He came to São Paulo to make a SOYUZ record. So he was around, and he did sessions for me on my record, and it's just a bit of a different feel.

Jonah: You've talked about how you're interested in the mess of music, how it can be informed from all over the place, in a way.

Sessa: Yeah, how music travels, and things influence things. Sometimes in my process, I want a song with a certain sound because I love another piece of music, right? I just listened, fell in love, and need to get it out of my system, like to make something with it. Just listening is not enough.

So there's a need to figure out how they create that energy. The music is air-moving. How did they move the air in this way? So you aim there, but you usually land somewhere else. Something gets lost in translation, but it becomes yours. Those things are really exciting for me. That's part of my process.

Jonah: How do you think you draw from São Paulo in your music?

Sessa: I made the previous record in Ilhabela, which is a city four hours from here on the coast. For this record [in São Paulo], people were around, and you could call in players to a session. I really took advantage of that. But in more general terms, the city's huge. It's the third- or fifth-largest in the world. [Ed: It's currently sixth. That's still huge!]

There are a lot of things I don't know about Brazilian music—there are people interested in song and tradition, but they're always also pushing. There's a lot of good music happening. It's not easy—it's art, it's culture. I'm not going to say we are a priority, even though there's a lot to be proud of in Brazilian culture, but it's good, and it's exciting to be here.

Jonah: You mentioned something about tradition and some of the music in the scene that you're in. What does that mean to you, or what does that look like?

Sessa: When I say tradition, I think about the lineage of songwriting, which in Brazil is a very rich, sophisticated art form that has many phases, but I guess all of that could exist under the sort of MPB [Música Popular Brasileira] umbrella, right? Brazilian popular music, which has echoes of the sixties and seventies productions by really important artists, all these big figures, but there's also a huge world that expands beyond.

The Brazilian guitar is something I've studied and try to operate in that tradition, and I'm so keen on teachers and players, and I really try to understand how they get the sound and how to record it. That's the work of the musician.

Jonah: You have some intentionality of those sounds by studying in that way, it seems.

Sessa: Yeah. I studied a lot of Brazilian guitar, like the nylon string and the classical guitar. This record is actually a bit of a . . . crisis is a very strong word. I played a lot of guitar on my first two records and on all the tours, and I really like the way I front a band and think about a sound; everything is through the nylon guitar. When I was making this record, I started to feel like I was out of ideas on the instrument, sort of like, you know, I've done it too much. I had no space from it. And at some point, that's where the keyboards come in, and also, the first records have more of a technique, and this last record, I play with more of a full hand strum. It's more rhythmic, and things get pushed a bit on that front.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmJonah Evans

The TonearmJonah Evans

Comments