Ahoy, email fanciers! This is your weekly Talk Of The Tonearm newsletter, filled with the joy of discovering music through history and context, combined with unabashed link-clicking. That's the modus operandi in these parts, and, as there's a lot to cover, I shall delay you no further from the task at hand. Enjoy!

Queued Up

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

In college, Robin Holcomb studied "Degung, which is West Javanese Gamelan music." That casual reference in our interview links Holcomb to a quietly radical academic experiment in American music. Lou Harrison became the unlikely stateside prophet of a Gamelan movement in the 1970s, hammering out his own metallophones and gongs to recreate Indonesian musical concepts. His obsession coincided with universities like UCLA, Wesleyan, and Wisconsin establishing intensive Gamelan programs. Composers studying under these programs learned to think in cycles, layers, and metallic textures rather than harmonic progressions. Students like Holcomb discovered that music could prioritize the decay characteristics of metal over piano attacks, and that compositional logic could arise from overlapping cycles rather than chord changes.

We could call the fruit of this academic network the 'texture generation,’ made up of composers who treated sound differently than their predecessors. Holcomb's description of creating "music that didn't come from changes" and letting "harmonic progressions kind of emerge" turns traditional songwriting on its head. Rather than harmony driving content, she works from texture and rhythm, allowing harmonic implications to surface naturally. At the same time, Peggy Lee's cello work demonstrates this philosophy in practice, using her "whole vocabulary" to create rich musical settings that sound "very full" without conventional harmonic density, emphasizing timbral relationships over melodic or harmonic roles.

The alternative-to-harmony movement offered American experimental music an escape hatch from jazz chord structures and European classical compositional techniques. Gamelan revealed an organizational system based on cyclical thinking and resonance rather than traditional harmony. For artists seeking to break free from bebop changes or twelve-tone serialism, Indonesian music offered a third path. Holcomb and Lee's twenty-year collaborative work continues to patiently explore these ideas, allowing meaning to accumulate through texture rather than theory.

Playback: Leo Chadburn Broadcasts a Radiophonic Lullaby of Industrial Decline → Leo Chadburn's use of shortwave radio, prepared piano, and bowed vibraphone to create "slowly revolving harmonies" explores the same texture-priority methodology. Also, Chadburn's academic background (he mentions his PhD thesis on speaking voices in music) suggests exposure to his own experimental music networks, possibly ones descended from collegiate Gamelan influences.

The TonearmCarolyn Zaldivar Snow

The TonearmCarolyn Zaldivar Snow

Don Buchla rejected the keyboard when he built his first synthesizers in the mid-1960s. The piano interface, he argued, imposed "the limitation of the piano" on electronic music, forcing new sounds through old patterns and reducing the imagination to eighty-eight keys. In defiance, Buchla created touch plates and random voltage generators that responded to pressure, movement, and the unpredictable electricity of human contact. His instruments demanded presence rather than precision, asking musicians to abandon muscle memory and respond to the machine's suggestions.

Fifty years later, Briana Marela spends her days at Buchla's Oakland facility, soldering reissues of those same groundbreaking instruments. But Marela's relationship with the Buchla goes deeper than a day job—her performances are a bold extension of Don Buchla's original vision. Equipped with a wireless microphone and reactive bodysuit, Marela moves from the stage and through audiences. "As you know, playing electronic music live is tethered by your tables and wires," she explains. "But this is a more human element… Just being untethered." Marela's wearable instruments respond to gesture and touch, turning her entire body into a controller that relies on the quirks of human-ness, much like Buchla's original touch-sensitive surfaces.

We can't ignore the word "untethered." Buchla's instruments were designed to untether music from Western harmonic tradition and the composer's conscious control. Marela's practice extends this liberation to the performer's relationship with space, audience, and self-worth. Her latest album, 'My Inner Rest,' features Marela repeating affirmative phrases like "I am the brightest star," signaling a personal transformation on par with the technological one. Thus, in performance, Marela trusts gesture over technique and lets vulnerability become strength.

Playback: From Soundribbons to Shoreline Symphonies — Knox Chandler's Creative Transformation → Knox Chandler's Soundribbons technique isn't too far off from Marela's untethered performance practice. Using iPads to process guitar in real time, Chandler creates what he calls "a meditative practice and a philosophy, requiring the musician to remain entirely present in the moment." Chandler states his goal was getting "back to what was truly me" after decades of collaboration. He found his authentic voice through technological release.

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

Spencer Cullum discovered pedal steel the old-fashioned British way: through liner notes rather than Nashville tradition. Cullum traced credits on Elton John and Rolling Stones records and followed the breadcrumbs to renowned session players. This led him to B.J. Cole, the London-based pioneer who famously took pedal steel outside of country music's confines. Cole became Cullum's teacher and unwitting guide into a musical underground that had quietly reshaped an American instrument's possibilities.

Cole's own origin story begins with his family’s television set. Watching the Perry Como show in 1963, seventeen-year-old Brian John Cole heard Santo & Johnny perform "Sleep Walk." The duo's dreamy instrumental was a hit with British audiences and bypassed Nashville entirely, offering Cole pure sound without genre baggage. He promptly traded in his model trains for his first steel guitar. Cole started playing London pubs with The Country Ramblers, but even this early 'country' context was uniquely British: mandolin, banjo, and pedal steel in smoky venues to audiences more familiar with skiffle than honky-tonk.

The breakthrough came in 1971 when Cole played on "Tiny Dancer," establishing him as the go-to pedal steel player for British artists seeking his ethereal twang. Throughout the seventies, Cole's credits accumulated across Marc Bolan, Scott Walker, and The Stranglers, each session pushing the instrument further from Nashville conventions. Cole then experimented with MIDI interfaces, ring modulators, and electronic effects, entirely throwing tradition out the window. Cullum's ambient-adjacent trio Shrunken Elvis is the latest chapter in this lineage, applying British pedal flavors to kosmische influences while working within Nashville's studio system. The pedal steel that Spencer uses for his ambient tones carries traces from that 1963 television moment, decades of London studio experimentation, and a commitment to hearing what the instrument could become.

Playback: Rolling Bones — Sylvie Courvoisier, Mary Halvorson, and the Art of Risk → Mary Halvorson's relationship with effects is in line with Cole's pioneering use of electronics. Halvorson also mentions how when her pedal board broke during a Geneva performance, "something was missing." Effects had become integral to her compositions, much like Cole's electronic experimentation became essential to his sound identity.

The TonearmElsa Monteith

The TonearmElsa Monteith

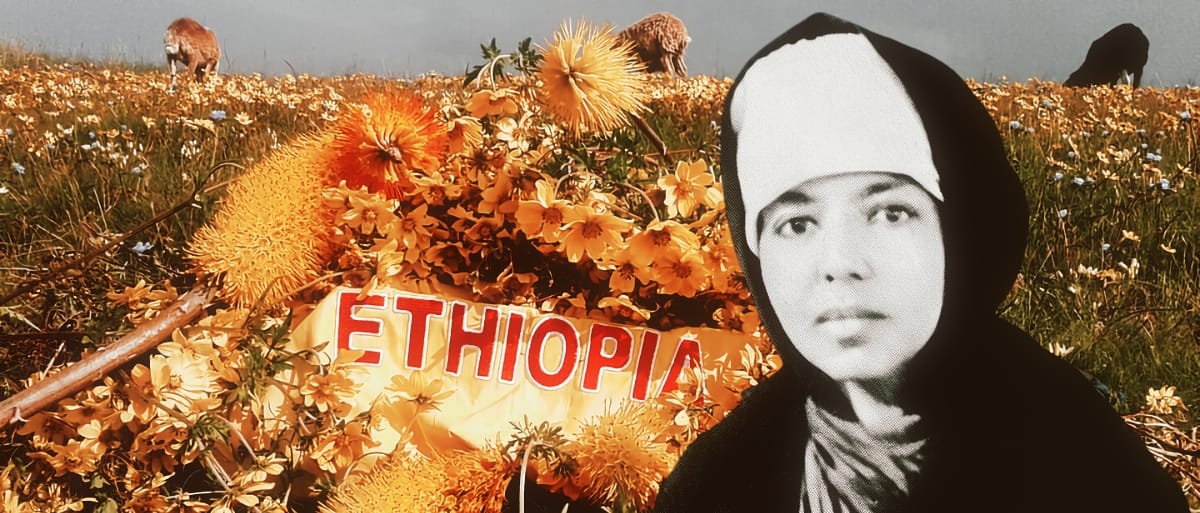

Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou recorded Souvenirs in the dead of night between 1977 and 1985, preserving her culture on magnetic tape. Meanwhile, the Derg regime recognized music's power to excite and inspire an oppressed populace and dismantled "Swinging Addis" to sever Ethiopia's connection to its musical identity. Emahoy, recording in shadows, fused together European classical forms with Ethiopian kignit scales as a kind of sonic camouflage. To censors, here was a nun playing recognizably Western piano, yet hidden within were the anchihoye, tizita, bati, and ambassel modes that formed Ethiopia's musical heritage.

Previous generations required studios and orchestras, but Emahoy needed only a piano and a cassette recorder. Those tapes became a product of her surroundings, capturing the creak of floorboards, distant birdsong, and the particular acoustics of rooms where Ethiopian culture remained. Her "elastic" tempo and mid-piece time signature shifts could be seen as an adaptability needed for survival under oppression. The music moved with fluid, unhurried resistance to rigid authoritarian structures. Free jazz, though obviously different than Emahoy's music, was likewise seen as subversive by repressive governments for the same reason.

The "ambient sounds of open windows and birdsong" become acts of preservation. Each recording is a time capsule, safeguarding entire ways of hearing the world. Nature itself is resistance, a reminder that small-minded evil-doers can’t legislate everything. Emahoy's recordings document the dream of a free Ethiopia beneath the notice of censorship, the promise of cultural resilience.

Playback: Dirt in the Machine — Hiroki Chiba Joins Hinode Tapes for 'Ita' → Piotr Kaliński's observation about art connecting rather than dividing countries applies to Emahoy's preservation of Ethiopian identity across cultural fractures. Hinode Tapes's incorporation of field recordings from Japan creates another parallel. Environmental sounds become part of the documentation process, just as Emahoy's recordings captured ambient room tone and birdsong as integral elements of Ethiopian sonic memory.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Andrew Staniland's JADE instrument converts dancers' brainwaves into spatial audio, building upon a largely forgotten lineage of adaptive music technology. Tim Roth's Soundbeam system converted movement into MIDI data during the 1980s, allowing wheelchair users to deliberately compose music through gesture and involuntary movements. Hugh Davies quietly developed instruments responding to breathing, eye movement, and skin conductance. Rather than forcing disabled musicians to approximate "normal" techniques, Davies created new forms of expression. These pioneers understood that different neurological configurations could become creative advantages rather than obstacles.

Staniland's "subconscious method of music making" opens avenues that neurodivergent musicians have explored for decades. Autistic musicians often possess perfect pitch and pattern recognition operating below awareness. Hypersensitive individuals detect microtonal variations unheard by neurotypical ears. Synesthetic musicians experience sound-color relationships that could be adapted to spatial audio mixing. Staniland credits his metal guitarist background for his willingness to explore these tangents, giving him an ethos of "if you don't create your own stuff, you don't make it." His classical music training, in contrast, often withholds "permission to tinker." This plays powerfully to his work in adaptive music, which mostly happens outside institutional structures.

But there is a troubling economic contradiction. Bio-responsive instruments like JADE benefit musicians with limited performance abilities, yet these same individuals often lack access to expensive technology. The disabled community has been hacking together solutions for decades through circuit-bent toys, Arduino sensors, and software that converts screen-reader navigation into rhythm. These grassroots innovations often prove more musically interesting than commercial counterparts because musicians who understand their own creative needs develop them. Staniland's vision of working with "neurodivergent creative artists" and "musicians who can't play anymore" opens important possibilities, but expect other exciting innovations from musicians who never played traditional instruments in the first place.

Playback: Enlightenment is Easy — Constructing Amina Hocine's Breathing Machine → Amina Hocine's PVC pipe organ responds to the performer's breathing, body tension, and attentiveness in ways that sound like bio-responsive instruments. She also describes how the instrument seems to scream with emotion if played forcefully or inattentively.

The Hit Parade

- This week's episode of the Spotlight On podcast features a terrific conversation with Matt Piucci of the legendary band Rain Parade. This one's tailor-made for fans of recent music history as Matt spills the beans on the early '80s independent music scene in Los Angeles and the rise of the 'Paisley Underground.'

- I'm skipping straight to the Short Bits: British comedian Stewart Lee writes about his love for the guitarist Derek Bailey and is then caught showing off on the telly. • If you're of a certain age (old like me), you'll remember when you could cut playable records from cereal boxes. Here's an article about that (NY Times gift link). • TIL Bad Seeds and Dirty Three member Warren Ellis owns an animal sanctuary in Indonesia. • Kate Bush's Hounds of Love album turns 40. "I still dream of Orgonon" remains one of the best lyrics to open a song. • Laurie Anderson talks about "O Superman" with nuclear policy expert Dr. Zia Mian. • Last Tuesday was The Tonearm writer Miguel Angel Bustamante's birthday, so you should revisit his excellent article on The Haunting Echo of Rubén Blades's 'Desapariciones'.

A Shout from the 'Sky

Experience the Joy of Newsletter.

Possible side effect: ecstatic truth. Apply now for your weekly dose.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Run-Out Groove

There you go! This one seems a little shorter, but there are five stories queued up for you. Why is that? Well, because we have many amazing new writers making debut appearances on The Tonearm this month. You should check them out (and our entire list of exceptionally good-looking contributors) and look for many new stories coming your way soon. We've got a lot of top-notch stuff planned. I'm shaking with excitement (and coffee).

Two asks: Firstly, please forward this email to a pal who would like to see the kind of cool things you're reading, or you can copy and post the 'View in browser' link at the top on your social media simulacrum. Next, drop me a line. I'd love to know what you think and if there's anything you'd like to see in our digital pages. Respond to this email, drop us a comment, or contact us here.

This week's going to be an especially busy one. Can you feel it, too? Hold on tight. As some Greek philosopher said, it's better to run alongside the cart than to be dragged behind it. Whatever that means. OK — I'm signing off. I'll see you here again next Sunday. 🚀

Comments