Brazilian percussionist Rogerio Boccato has spent decades collaborating with some of jazz's most respected artists, including Maria Schneider, John Patitucci, Brian Blade, and Kurt Elling. His work appears on three Grammy-winning albums and countless acclaimed recordings. But his latest project, the trio Cardume, strips away the familiar structures of jazz performance to create something more elemental: three musicians listening so intently to each other that their music becomes a real-time conversation, shaped entirely by what happens in the moment.

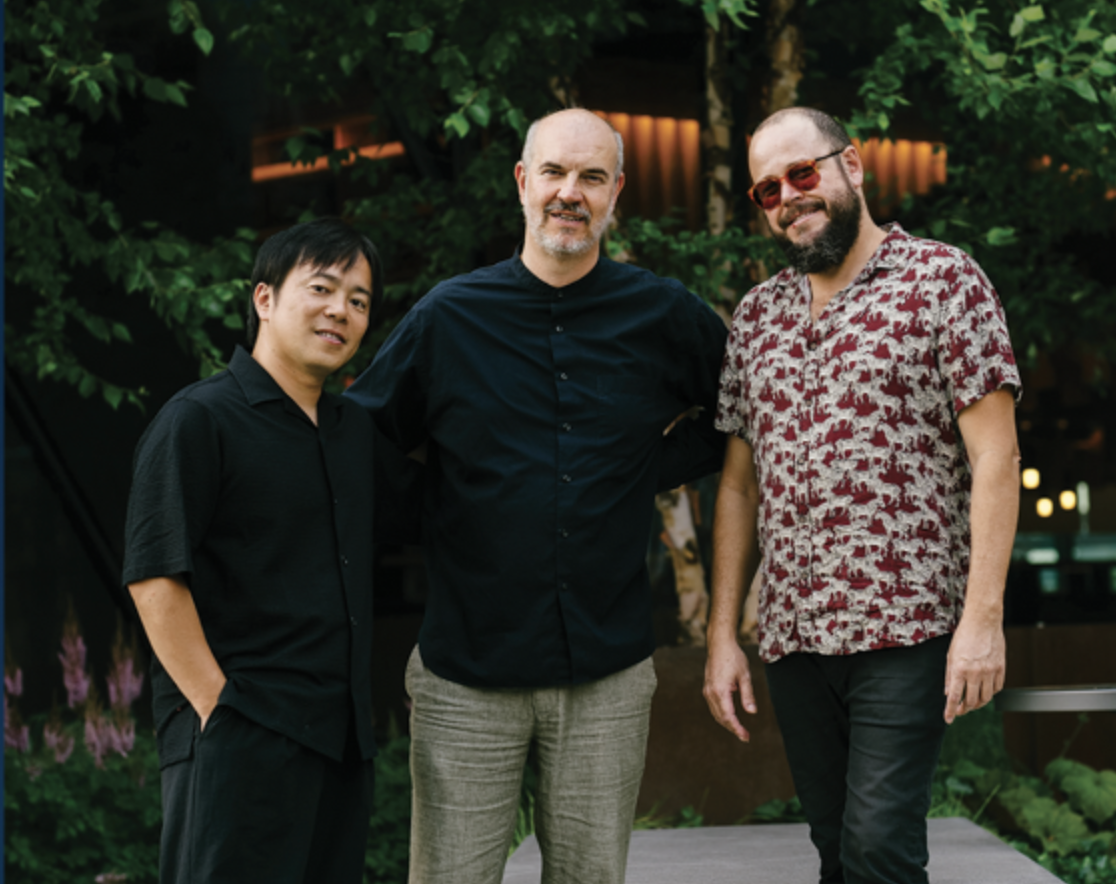

The name Cardume comes from Portuguese, meaning "school of fish." No leader directs the group, yet they move as one organism, each individual responding to subtle shifts in pressure and motion around them. One fish changes direction, and instantly the entire school flows with that movement. Boccato's trio with Keita Ogawa and Cleber Almeida works the same way: someone plays a sound, and that gesture prompts an immediate response that sends the music somewhere new and unplanned.

Lawrence Peryer: How does the ‘school of fish' concept work in Cardume’s music?

Rogerio Boccato: I think it's a good description of what happens when we get together to play. I have these two friends and very close companions in this project. Every time we play together, there's this easy connection. We just play, smiling at each other the whole time because we're in this conversation.

I play with Keita Ogawa here in New York—we are part of many projects together, and he plays the drum set and a lot of percussion. Sometimes, when we are together, we build a gigantic percussion set instead of just drums and percussion.

When I visit Brazil, I meet my friend Cleber Almeida in São Paulo, and we also share a similar connection. My dream was to put these two duos together. This started this vision of the cardume—the school of fish. When you see fish moving in the water, it seems like something happens that prompts a response, and everybody goes this way or that way, and it's immediate.

I noticed, when I started listening back to the recording we made, that exactly what was happening was happening. Someone made a sudden move, played one sound, and that generated a different direction. Everybody is now going in this new direction, and it’s very subtle, but when you listen back, you think, "Okay, this is the cardume moment." You can clearly hear that at that moment, something happened and everything changed immediately, like a drop of a dime. So when I started listening to that, I said, "Okay, this is a very good image to describe how we play."

I have to say that connection and trust are there, even when we go on stage, "Okay, what's gonna happen?" Then something happens that prompts us to move, and we're listening to each other very intensely. That's the story of this group. That's how it works.

Lawrence: When the three of you step on stage, do you know how it's going to begin? Who starts? Who makes the first sound?

Rogerio: Every night we have a context. For instance, we were at The Chelsea Music Festival, which was our first concert of a week-long tour. We played in this beautiful German Lutheran church here in Chelsea. So Ken Mazur, the director, and Melinda, his wife, are announcing the program and about to bring us on stage, and we are like, "Okay, how are we gonna start this? Oh, maybe we can just start clapping. Let's just start with the clapping sound." Then Cleber said, "Okay, but then we come in, everybody's gonna be clapping, we just keep clapping, and then we take a seat, and that's it." So in that moment, we just decided, "Okay, that's how we're gonna start."

But through the concert, I make the choice. Sometimes it's "Okay, Cleber, why don't you start this one?" or "Keita, why don't you start?" Sometimes I just start—I don't have to ask permission—but each of us will have the freedom to choose a sound, to choose a vibe, based on a contrasting situation of what happened before.

So there’s always a context, right? At the next concert in North Adams, Massachusetts, we had a beautiful dinner before the concert, like incredible food. So we were walking to the concert thinking, "Oh man, I feel heavy. It’s time to sleep." We look at each other, "How are we gonna start this?" And the word was ‘slow.' Everybody felt slow. So that's how we started. So it's always based on what's happening in the moment.

Of course, we're always looking for something new that we haven’t done before. We have the same setup, we have the same instruments, but many different sounds, textures, and colors. It's like a limited palette, but the combinations, the context, and all these inputs from what’s happening in the moment —that's what shapes it.

Lawrence: It sounds like it’s really about the moment and the mood. There's such a small gap between your lived experience and what you're creating on stage.

Rogerio: Yes, totally. It's a good description, and I feel like this is true improvisation. It takes a long time to train and master the art of playing over changes, forms, and standards. But it's very different than if we start a conversation. You start from scratch. It will be something unique.

As I said, we have the same instruments, but it’s always a whole different experience. What happens in the studio is the same idea—it's a conversation we're having now. I feel that this is the true form of improvisation, and it relies on trust. We know that we will be able to make something happen here. We will come up with a story and a theme.

When you say something is totally improvised, people go, "Okay, I know what's gonna happen, like noises and free crazy people going in different directions.” That’s possible, but it doesn't describe what we are doing. We're complimenting each other and listening so hard to each other, which is the point.

On this tour, I was bringing this message of, "Okay. What we are doing here is an act of resistance. We are really listening to each other intensely." I can tell you so many times that when I had a plan—“Oh, now I'm gonna go here in this piece”—something changed in the music. That's why it works, because the three of us share the same spirit of trying to build something together and are open to letting go of our own ideas when it makes sense.

Of course, we love each other. We are friends. Yes, we want to build something together. So there's all this positivity, all these connections, and that's why it works, because nobody's there saying, "I have this great groove that I wanna play and show everybody.” There's nothing like that. So it works because everybody's respectful and open to what's going to happen. There's no agenda, there's no preconceived conversation, just like we are in this conversation. So, bringing anything pre-made doesn’t work because it’s going to sound totally out of context.

Lawrence: You've had such a fascinating career, whether it's the work you did in Brazil, playing with João Bosco, or in New York with Maria Schneider, John Patitucci, and countless others. Sometimes you're a band leader, sometimes you're there in the service of someone else's vision. Could you talk about how you transition between being part of someone else's thing as opposed to leading an ensemble?

Rogerio: First of all, I'm very grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate and be together with the list of people that you mentioned. Those are my musical heroes, and I'm just always in awe that I can look back and say, "Wow, I was listening to Patitucci when I was like eighteen, and then we were doing this thing." So many times I've pinched myself thinking, "Wow, this is happening."

In my projects as a band leader, collectively composing and creating is very central. I have another project, a quartet: piano, bass, drums, and saxophone. We are playing other people's music. So, let’s say standards, although I chose Brazilian composers, but the spirit's the same. We have to be in the space recomposing that music—not just playing it like the original or any pre-made arrangements. It's always with this spirit of creating together. I want to hear the melody; I want to hear those compositions, right?

When I'm in a position of a sideman and supporting other artists, I go with their vision. Most of the time, it's a more traditional setting where you have a tune they wrote, and there are roles to be filled. You need to play this kind of groove or color here—ideas that are preconceived. It's a lot of talking, a lot of charts written, and I'm okay with all that. I mentioned that to me it's way more fun to be creating in the moment, but I have a deep respect for people who are masters in this tradition of playing over forms and chord changes.

Now, in terms of the geography. I feel I should point out that I'm from Brazil, which is a country that has an immense musical tradition, especially in the percussion area. So a lot of our music is based on African music because Brazil is the most Africanized place in the Americas. The majority of the people who were brought from Africa to be slaves were in this area. So it's in the culture, it's in the food, in the language, it's in the music. As a percussionist, this is a big part of who I am, but it didn’t start this way for me. I started playing drums based on American music like jazz and rock, like anyone else in the world—everybody's listening to American music.

So I'm really loving jazz and swinging straight ahead with that kind of stuff. But eventually, some friends of mine saw my path and said, "Look, you need to start looking at your own music and your Brazilian background." I was like, "No, I love Elvin Jones and Philly Joe Jones and Jack DeJohnette and all those guys." But being born and growing up in São Paulo, which has eighteen million people, I didn't grow up with traditional regional roots, like you do in different parts of Brazil. It's like growing up in New York—my roots were a mix of everything because in São Paulo you have contact with everything. So, I was there at every jazz concert they brought to São Paulo, soaking in and drinking from that water, while also being exposed to a lot of Brazilian styles, without even noticing. In São Paulo, we were exposed to everything.

So, for a while, I was thinking, "Man, I don't have any regional roots." But when I moved to New York, I looked back and thought, "Wow, what I have is a mix of everything, including jazz." I think that's what made it possible for me to interact and relate to the jazz artists that I've been playing with. Because I have an understanding of their language, I bring something more personal in many cases.

It's not because I'm from Brazil that I am in this band or that band, but because of this amalgam of all these styles and influences. In some other situations, they need someone who can play pandeiro in this specific Brazilian samba style. But maybe eighty percent of what I do is based on this mixing of all these styles, rather than just bringing the Brazilian flavor to the table.

Lawrence: How has teaching affected how you think about your own playing?

Rogerio: I learned more about Brazilian music when I moved to New York than in my whole life in Brazil. That is because of the teaching. Let me ask you this: How do you produce the sound of the "th" in English?

Lawrence: Put your tongue and your teeth and breathe hard.

Rogerio: Exactly. That's the situation that I was put in. I come here and was asked, "Yeah, but how do you do this?" I didn’t know how to put it into words. So I had to do a lot of research on my own music and background to understand what was happening, to have a real grasp of the cause and effect—what made this music sound like that, to be able to transmit that to other people.

Because of my teaching here, I had to learn a lot more about Brazilian music than I ever researched in Brazil. Because you speak English, that “th” comes naturally to you—the sound, you just don't think about it. That's how I was playing. Eventually, I had to stop and think about it, and think, what are the reasons that we do this and not that? I had to do deep research, listening to many records and trying to find the patterns. Not necessarily musical patterns, but what was common to define a style. So now people ask me, "Okay, so what makes samba?" I have an answer. I can give you a two-hour lecture on that because I researched it. "So this is what makes samba."

I love sharing and the teaching aspect. I'm not one of the musicians who have a teaching gig because I need a steady income. I really love it and I like it when it's balanced, right? I have like fifty percent of my time teaching and fifty percent playing, performing, and recording. And it definitely informs how I play, because once I started researching and finding those conclusions, I was like, "Oh, so if I really wanna play somebody in a traditional grounded in the tradition, I have to do this." So it cleared up my mind and opened up a lot of possibilities for me.

Lawrence: Being an ensemble of three percussionists—how do you make room for each other?

Rogerio: I observed something during this tour because we spent six days together, and it was the first time the three of us had the chance to do that. I rented this minivan to load all our gear, and it's just the three of us in the car.

We drove for a good amount of hours. I observed that in many instances, there was a long period of silence while nobody was saying anything. Sometimes we would listen to music and make comments about it, discussing what was going to happen in the next town or reminiscing about something that had happened at the previous concert. Of course, we had many conversations of all kinds, but many instances were just silence. Nobody was saying anything. Nobody felt the need to fill the space with words. That caught my attention because I've been in many vans throughout this country and other places, and sometimes I think people feel the need to fill the space; silence can be awkward.

There's something cultural about it, too—that you just feel uncomfortable if nobody's saying anything in a group of people. But I noticed that the three of us just felt so comfortable in the silence. I think that translates directly on stage. For example, I’ll turn to Keita and say, "Keita, please start us on this tune." We're just waiting, and he has a minute or whatever. We just wait until we feel it,

We have some video recordings from a concert we did last summer in the Chelsea Music Festival. I’m watching the videos, and many times I’ve observed Cleber just waiting and looking, waiting for the time to come in. Or Keita, where there was no need to say something immediately. This confirms that we are on the right track, because in a conversation, you cannot speak the whole time, even if you have great things to say. A natural rhythm and flow are needed. With this trio, everything goes really naturally. We don't need to force anything.

Lawrence: Somebody who can be a great conversationalist is a wonderful thing to have around. Somebody who could sit in silence is a pretty wonderful person, especially on a long trip.

Rogerio: Exactly. We had both—we had many meaningful conversations and also listened to music, and that was the other thing that was really interesting because Cleber was like, "Okay, Keita hit us with some nice music.” He landed on a beautiful record by the Peruvian singer and composer Chabuca Granda. Wow. What a beautiful record. The whole record, all the tunes in the record, beautiful orchestration, beautiful playing, and the compositions and her singing. We were in awe.

So it was nice to have that kind of shared moment, and then I said, "Okay, I have this other incredible album where every track is amazing." That was the theme. The albums that are like a whole album that you can listen to, and every tune is great. There was a lot of sharing, but then again, good conversations were followed by some silence, which is great because it's all balanced. I must say, I feel it was a very successful tour.

Lawrence: Are there any specific instruments or collaborators that you'd be excited to have interact with this ensemble?

Rogerio: I think more about people than instruments in general. I think about Danilo Perez, the great pianist. We have collaborated in the past, and I know he shares the same spirit of jumping in. For this first album, there was one tune that, when I listened back, I thought, ‘Oh, it’d be nice to send this to Danilo and just say, ‘Look.’ We just created this in the moment. Just put the headphones and play whatever you hear from minute two to minute four or something.'" I had that kind of idea, but based on the people more than the instruments.

Also, Lionel Loueke, a great guitarist from Benin. We have collaborated in the past, and we’re considering other projects for the future. He's the most percussive guitarist on the planet. Just amazing what he does with rhythm. So I think about people more than the actual instrument. It doesn't really matter because I'm sure that if the person has the right spirit and the right mindset, it’s going to work, no matter what kind of sound.

Lawrence: What do you hope a listener takes away from these recordings? Are you seeking to entertain, educate, or enlighten them? Or do you not think about the audience?

Rogerio: I'm going to speak from the performance perspective, which is where we had people in front of us, and interaction was very important. I really want them to experience the possibility of three different people using color, sounds, and texture to create something that has a shape, that has a story, that has a beginning, middle, and end. The audience is a big part of that experience because there's an expectation and an energy that happens in the room.

We’ve found that our listeners are engaged in our process, so I created a few prompts to involve the audience. For instance, I said, "Okay, is there a nurse or medical doctor in the house?" When somebody raises their hand, I said, "Okay, what's the easiest way to find our pulse, the heartbeat?" They demonstrate how to do this on your wrist or throat. Then I said, "Okay, everybody, find your pulse. Lightly start tapping. I know it's going to be this confusion of tapping, but stay your ground. Keep it going. Don't follow other people—feel your own pulse and bring it. We're gonna play on top of that." The people got engaged, and they kept it going. It was like a percussion section in front of us, and we just played over that. We did this twice, and in one case, everybody caved into one pulse.

In other situations, we had this amazing gong that Keita brought—a Korean gong. It had a clear pitch, like a very clear tone. I invited people to sing. I said, "Okay, when you hear this, sing whatever note you're hearing.” It was like this beautiful drone. Again, we played on top of that, and it was a moment of connection because I said, "At least for a minute, we are gonna sing the same thing. We're gonna be connected here." It's something that translates hopefully to the experience of each other outside of that concert moment. Those are examples of direct engagement, but I also feel like in this collectively improvised situation, our energy on stage is so strong that it brings people in. They notice that we are there creating something out of nothing, and that is something that brings them in because it's an experience that is happening now.

Lawrence: Is there a percussion tradition that you see as one you'd be interested in exploring or that you feel, "Ooh, that looks good to me." Is there an instrument you'd love to pick up and play with?

Rogerio: There are many. In Africa, like in Senegal, there is a tradition called sabar. It’s different drums, actually, and it's always connected to a dance. They have long phrases that they create, memorize, and play in unison. It’s very strong and powerful. They also improvise, following the dancers. It's similar to a style that we have in Brazil, but for Carnival, because it's three hundred fifty drummers playing in a group of four thousand people dancing, and you have twenty to thirty of those groups, parading through Carnival.

They have a tradition in Senegal where they use one stick and one hand for those drums. That is also something that happens in this one particular drum in the samba tradition. So I see some connections, and it's just incredible how they can come up with all those phrases. Because also in Brazil, the master of the drum section comes up with phrases that the whole ensemble plays in unison. It's complex, but those people are not musicians in the sense of professional musicians who went to school and trained. No, they are just normal people like a plumber or a post office guy or any kind of profession that they have, and they do that in their spare time. But when they see them playing, they are the specialist of that style and the way they can memorize three-minute long arrangements. It's really fascinating.

So that's just one example. But there are many other African styles, like in Nigeria and Ghana.. Each of those places has numerous traditions, and I’m always researching. With the advent of YouTube, it has become a little easier to be there without physically being there. But, of course, being there, talking to people, and having the chance to ask questions or observe in person would be way more interesting.

I had the chance to play with a Korean musician many years ago—probably around thirteen years ago. She exposed me to classical Korean music. I had no idea what that was—the instruments and the whole mindset. I became fascinated. It's such a deep tradition and very different from things that I am familiar with. So I'm always intrigued by so many other traditions in the world. There's so much interesting music happening, and I see connections to my own process. But with Korean music, there is very little connection, but I am still interested in exploring.

When I have students from Korea here in Manhattan School or NYU, I always ask them, "So are you aware of the traditional Korean music?" And some of them are not, like I wasn’t into Brazilian music in my early days—I didn’t know what was happening when I was growing up.

But then, eventually, I'm thankful that somebody older came to me and said, "Look here, you gotta research this. You gotta be aware." I've had some students who did that with Korean music, and that transformed their process, too. I think it’s very important to look into our own backgrounds and context, and try to build from there, not just exclusively, but definitely as part of what makes you unique and brings something uniquely to the table.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

The TonearmMiguel Angel Bustamante

Comments