Very big, very Black, and very blind, with a passion for honking on several woodwinds at once, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, aka Roland Kirk, originally Ronald Theodore Kirk (1935–1977), evolved album to album, in the words of critic (and occasional scribe for The Tonearm) Dave Segal, aka DJ Veins, in conceptual leaps tantamount to the Beatles'. But where the Fab Four tended to shed skins morph by morph (at least through the end of their psychedelic era), Kirk rolled history and his private passions into one great sphere, displaying sides, facets, to fuel his interior visions. A New Orleans–style strut could flip into swing, then bebop burbling, ending in free-jazz freakfeast with all hands on deck boat-whistle hooting—which sounded uncannily like the New Orleans–style strut, joining Alpha and presumptive Omega of jazz history in a floppy-knotted loop.

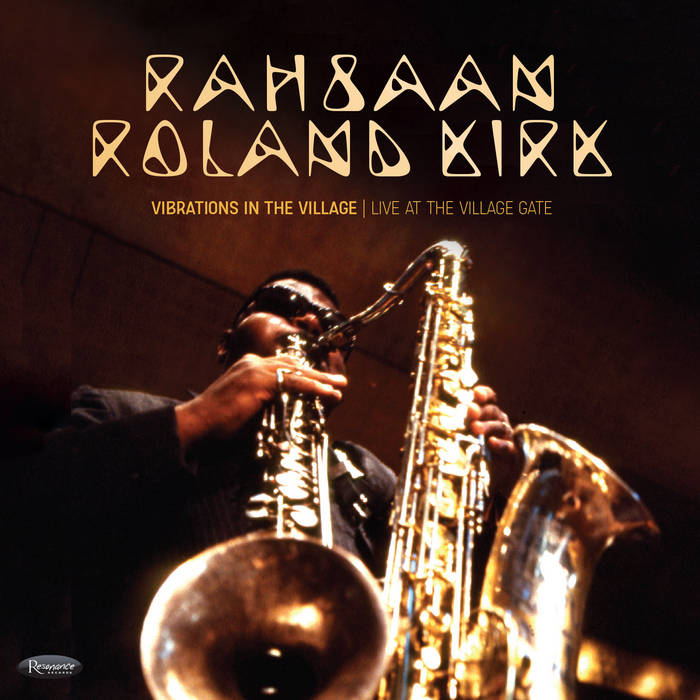

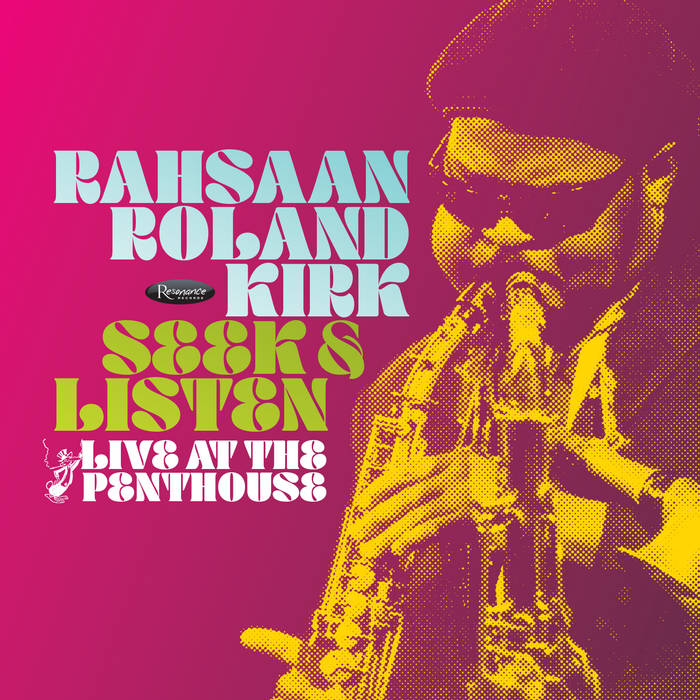

Two newly released archival live sets, Vibrations in the Village: Live at the Village Gate and Seek & Listen: Live at the Penthouse, recorded in New York City in 1963 and in Seattle in 1967, respectively, find what the sightless Kirk termed "bright moments" in abundance, even with cultural commentary tossed brazenly into the salad. "Ecclesiastics," penned by Rahsaan's old bandleader Charles Mingus, leads off with his multiple horns invoking a heavy church organ. Mingus (with Kirk backing him up) on his 1961 session screeched, grunted, and rent his throat in the name of Our Lord; two years later in NYC, Rahsaan shelves God for a presumably facetious poke at Governor George Wallace down in Alabama. Give Wallace your money, calls out the bandleader in his broad, flat voice, Wallace needs your money. He's needy.

I say presumably facetious because we've got a Black man calling out a white man who proclaimed, at the dawn of 1963, "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever"—lines written for him by Ku Klux Klan organizer Asa Earl Carter. Easy enough to call . . . except Kirk's tone comes across curiously tender. Almost like he wished to hold that hateful lunatic to his chest, to hushabye and coo him to slumberland.

Other Vibrations highlights include "Oboe Blues," Kirk, after the intro, laying aside his saxes for the snake-charmer nasal tonalities of the titular horn; a sweet and icy flute for the standard "Laura," complete with that overblowing and singing through the instrument that would spark Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson; and Rahsaan standby "Three for the Festival," spearheaded by fleet-fingered pianist Jane Getz, anchored by bassist Henry Grimes, climaxed by a further-out flute workout. Indeed, our man self-duets here on flute plus nose flute—a favorite stunt during which he'd sometimes praise the erudition of his own proboscis.

Quoth Adam Dorn, son of Kirk's frequent record producer Joel Dorn, "My father would say time and time again, 'They're going to be talking about Rahsaan 300 years from now.' My father knew and took very seriously that he was the trusted co-creator and steward of the vision Rahsaan had in the studio. This was uncommon in the jazz record-making work often characterized by the ubiquitous 'set up the mics and simply record' manner."

"[Kirk] was a beautiful cat," recalls his frequent sideman Steve Turre (not, alas, included on either of these archival sets), "but he'd tell it like it is. When we played 'Satin Doll' at the club, afterward he said, 'We're playing Duke Ellington. Don't be playing no J.J. Johnson. We're playing Duke Ellington. Don't be playing no bebop.' He told me, 'As far back as you can go, determine how far forward you can go. You got to know where you're coming from, to know where you're going.'"

Ellington's quite in evidence, though, upon the Seek & Listen set—a sprawling Ellington medley featuring "Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye" into "I've Got It Bad (And That Ain't Good)," into "Sophisticated Lady," into, yes indeed, "Satin Doll." The flute from "Goodbye" slides into the anxious lament of a vocal in "Got It Bad," then more flute, then a dry sax jumping to the front. "Satin Doll" signals the return of the more-horns harmonizations, followed by solo outings on a few instruments. Etching a gandy-dancer's line between Ellington elegance and a touch of the gutbucket (then back to a swirling flute)—Kirk keeps to Kirk's words. He plays no bebop.

Another medley, probably a set-ender, mushes Rahsaan's own "Blues for C & T" with "Happy Days Are Here Again" and "Down by the Riverside." Playful avant-garde rules the roost in a flash, with lips-to-mic vocalizations, shimmery hand percussion, and a little rootie-tootie flute. Then the blues portion in fleet, tearing tenor runs, dry drum breaks courtesy Jimmy Hopps; from there, a marching-band-on-acid approach simpatico with Kirk's contemporary Albert Ayler—those simple, rousing tunes in wavering woodwind lines bolstered by Hopps' backbeats. Our leader gyrates off-mic, but his gospel shout of "I ain't gonna study war no more!" comes across. Then a short stretch of "The Star-Spangled Banner," so we'll ponder our nation studying war, for sure.

"Roland was psychic," in the words of Penthouse sideman Steve Novosel. "They say unsighted people have that sixth sense. Once we were in England, riding in a cab, and Roland says, 'Hey, cabbie, you made the wrong turn.' Now, how the hell did he know that? He knew. The cabbie had made the wrong damn turn.

"We were playing in the [Village] Vanguard and in the middle of the set, Jimmy Hopps said, 'Roland, there's a guy back there with a tape recorder.' [Kirk] reached in his [customized] cane and pulled out that .38. He said, 'Where is he, Jimmy, where is he?' He ran back there and snatched the tape recorder out of the guy's hand, came back on the bandstand, and gave a long speech about bootleg recordings. While he's doing that, he's stomping on the tape recorder, just destroying it. He did things like that."

Zev Feldman, who prepared both Kirk sets for release, acts as co-president of Resonance Records, the releasing label; he's also a consulting producer on archival and historical recordings for the Blue Note label. A dedicated archivist and passionate about bringing previously unreleased material to light, he worked on a jaw-dropping 26 releases in 2016 alone; Stereophile magazine dubbed him "the Indiana Jones of jazz."

Feldman's work includes acting with the estates of prominent jazzers, including those of Bill Evans and Wes Montgomery. He helped bring to light two prominent archival recordings from Thelonious Monk: Les Liaisons Dangereuses, recorded in 1959 for a French film but not released until 2017; and Palo Alto, a live set from a California high school in 1968, recorded by the janitor, kept by the teenager who booked the show, and not released until 2020.

On top of all that, Feldman runs his own archival label, Time Traveler Recordings, with recent releases from Roy Brooks, Kenny Barron, Carlos

Garnett, and more to come. He was kind enough to take some questions over email.

Andrew Hamlin: What are your earliest memories of listening to Rahsaan Roland Kirk—which albums, standout tracks, etc.?

Zev Feldman: For me, the very first album I had was Kirk's Work on Prestige with the great organist Jack McDuff. I bought it at the Tower Records in Rockville, Maryland, when I was about 18 years old and just getting into jazz. Someone at the store recommended it. I really enjoyed it, although I don't think I got the full message of Rahsaan's greatness at the time. It also introduced me to all these different instruments like the stritch [a straight-bodied alto sax] and manzello [a modified soprano sax with an upturned bell].

After that, when I was working in the mailroom at PolyGram, they had an employee discount purchase program, and I used it to purchase the Rahsaan: The Complete Mercury Recordings of Roland Kirk box set and really grooved on that one a lot. I especially loved the stuff recorded in Europe. I loved all eras of Rahsaan's music, although I'm not an academic, and others can speak to his greatness much better than me.

Another memory I had was when I was about 17 or 18 years old, I saw the Supershow, which was a concert film that had Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, and others, and Rahsaan played on that with Buddy Guy and Jack Bruce. It was a moving experience for me.

Andrew: How did your views on Kirk's work grow and change over the years?

Zev: As I listened to other recordings, I could tell there was an evolution in his music, as those first records I heard were some of the earlier recordings. He had so much to offer.

Andrew: How did the Kirk tapes in the two new archival sets come to your attention?

Zev: I've known about the Penthouse tapes for fifteen years or so, when I first met Jim Wilke [jazz radio host and longtime Penthouse tape archivist] and Charlie Puzzo, Jr. [son of Penthouse founder Charlie Puzzo Sr.], and have long wanted to put them out for a release.

The Village Gate recording came to me by way of audiophile speaker maker and engineer Jeff Joseph, of Joseph Audio, who was friends with Ivan Berger, who recorded the music. There was a documentary filmmaker who was working on a documentary about Rahsaan and hired Ivan Berger to record audio of the show to be included in the film, but the filmmaker died before the film was finished, and we don't know what happened to him. But Mr. Berger kept the audio tape he had all these years.

Andrew: The Gate set features three different pianists—Horace Parlan, Melvin Rhyne, and Jane Getz. Do we know why Kirk switched pianists three times in a two-night stand? How do the pianists compare and contrast?

Zev: We do not know why he had that many pianists there at the Gate, but according to Jane Getz, she was likely just hanging out there because she was friends with Henry Grimes. Perhaps he was auditioning people? Your guess is as good as mine, and it would be hard for me to say.

Andrew: Any thoughts on Kirk's other sidemen from these sets? I found Henry Grimes' bass playing on the Gate set a little hard to hear, but fascinating.

Zev: I think all the sidemen are terrific. For the Village Gate recording, I think it's amazing that you have all these musicians in the band. It was special to hear Melvin Rhyne on piano, as he's most well known as an organist with Wes Montgomery. All the other contributions were great. I don't know a lot about the drummer, Sonny Brown. For the Penthouse recordings, there's a special cohesiveness with Rahn Burton, Steve Novosel, and Jimmy Hopps. They were a working band that sounded great together.

Andrew: What are your personal favorites from each archival set, and why?

Zev: I love "Three for the Festival" off of the Village Gate recording. It's one of my favorite Rahsaan tunes, and anytime I get to hear a new version of it, it's awesome. From the Penthouse, I love "Alfie" and the medley with "Happy Days Are Here Again."

Andrew: Was any tape left over from either the Gate or the Penthouse? Anything you regret not including?

Zev Feldman: No, and no regrets.

Andrew Hamlin: What are your plans for 2026? What can we look forward to?

Zev: I'm going to have 11 releases coming out in April that will be announced at the Record Store Day announcement sometime in February. Stay tuned! I have lots of great and exciting projects I can't wait to share news on.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmBill Kopp

The TonearmBill Kopp

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments