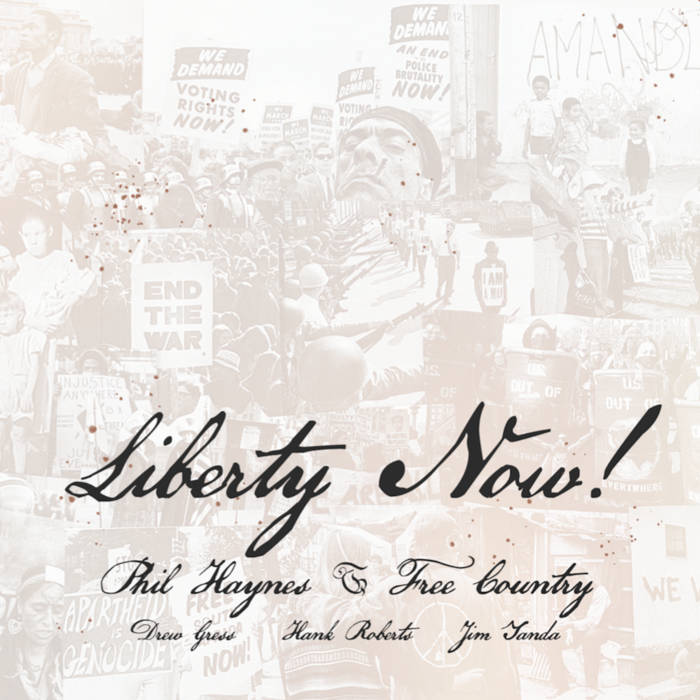

Drummer Phil Haynes formed the string band Free Country in 1997 with cellist Hank Roberts, guitarist Jim Yanda, and bassist Drew Gress, creating what one reviewer called "jazz-grass"—a hybrid that brought improvisational intensity to folk traditions. Their American Trilogy traced the nation's sonic evolution: pre-1900 ballads and Stephen Foster on the self-titled debut, Aaron Copland through Hollywood cowboy soundtracks on The Way the West Was Won, then the turbulent 1960s on '60/'69: My Favorite Things, veering from Coltrane to The Beatles. After completing that cycle in 2014, Haynes thought the band had exhausted its purpose.

Ten years passed. The sound wouldn't leave him—that particular chemistry, four players who had learned to showcase each other with unusual generosity. Haynes planned a return focused on original compositions rather than historical interpretation, and the quartet gathered at Electric Wilburland Studios with that intention. Then two shocks arrived in rapid succession. The 2024 presidential election delivered results that left the group reeling. And hours before the first session began, they learned that trumpeter Herb Robertson, a friend, collaborator, and transformative influence on each member, had died.

Liberty Now!, released via Corner Store Jazz, carries both griefs. Disc one presents twelve new pieces that Haynes later recognized as an inadvertent protest record filled with political urgency and personal loss inseparable from the performances. Disc two gathers the most pointed material from three decades of recordings, constructing an alternate history lesson that includes "To Anacreon in Heaven" (the drinking song that became the national anthem), The Beatles' "Revolution," and "What a Wonderful World" stripped down to its raw emotion. The title updates Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite for this moment when liberty requires defending.

Phil Haynes recently returned to The Tonearm Podcast for an impassioned conversation with host Lawrence Peryer. Haynes reflected on Herb Robertson's death and its effect on the album's sessions, the political themes embodied in Liberty Now!, and how the band considers which traditional songs they could authentically perform.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the audio player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: When Free Country went into the studio at the beginning of this project, you thought you were making a different record. Could you tell me about the album you thought you were making and how it transformed into the album you made?

Phil Haynes: Well, I thought ten years ago Free Country had run its course. We'd completed our American Trilogy—Free Country in 1997 with pre-1900 music, The Way the West Was Won covering 1900 through the 1950s, and '60/'69, the decade of the sixties, everything from Burt Bacharach to Coltrane. It was meant to be a band that could communicate jazz ideals in a really NPR-friendly kind of way.

But of course, I picked the right guys so that there was honest romanticism in everybody in the band. It grew, and it became clear from the beginning that we had to have political discussions about it all. I remember I used to think that if it was a good melody and it was American, well, then we ought to do it. And then Hank Roberts said, "Do you really think that four white guys ought to be recording certain of these tunes?" I was like, "Oh no, that's right. We probably cannot." So this band was a political awakening, I think, for all of us, because you can imagine the conversations that went on.

Anyway, without major label support—I'd always hoped somebody would pick up the mantle—I thought it was over. And then the sound of the band for the last ten years never went out of my head. Reflecting on COVID, trying to figure out what I could do, and as I searched for very much younger-generation collaborators, I realized that the only thing I could do immediately was to take on some unfinished business. And I had always thought that if we were ever to make another record, it would be of our music, instead of being a cover band, which the band was brilliant at. Let's take that sound, let's take that heritage, let's take that chemistry, and turn it to our own tunes. So it was supposed to be Free Country, quote unquote, our music.

And that's what we went into the studio to do. And then, of course, the election intervened, and personal loss—Herb Robertson passed away. We literally found out as we were loading into the studio, one thing after another. But I don't think I realized it was a protest record until a couple of months later, when I started going through the material.

Lawrence: You've said there's Phil Haynes before Herb Robertson and Phil Haynes after. You're loading into the studio, and you get the news of his passing. How does that impact what results?

Phil: Well, you can imagine it was huge, because each of us—Hank, Drew, Jim, and I—had all recorded with Herb individually over the years, over decades. He was not only a close friend and colleague, but also the first important person in my generation to pass. He helped to change our generation in such a way that now it doesn't seem to matter whether you're into avant-garde jazz, avant-classical music, progressive rock, hillbilly music—everybody knows about open improv.

When I got to New York in the mid-eighties and met Herb Robertson, it was like, "Oh, that's what free is." I had been labeled 'free,' but I didn't know what that meant. He could take the most common, literally dime-store toys never meant to be instruments, and he saw their potential and then revealed them as serious musical instruments. He called it ritual music, not free music, because he thought that we needed to come to it out of silence, out of respect, trying to become vessels for something greater, to get ourselves out of the way. That greater community, of course, is accessible through the subconscious.

And it wasn't just that you came out of silence, it was the quietest sounds. And all of a sudden, things that I had been doing when I was in hotel rooms trying to not be heard, all of a sudden, these things that I had been doing that I just thought were experiments and ways to keep myself creative in restrictive circumstances, all of a sudden they were opened as this—it was like this magic curtain opened. He opened that for many of us.

Well, anyway, I used to joke that if the worst happened and there was only a burning hulk of the Empire State Building left, and Herb Robertson was there, he could play a solo concert on it and people would come around and cheer. He had the ability to take anything and make music with it. I never saw anything like it.

Lawrence: When you describe what you saw in free music for him, it seems like there's a willingness to be vulnerable, because that's kind of scary to pick up an object and decide it's going to be musical.

Phil: Yes. My whole life, I've been trying to frame sounds—because percussionists are sound generators and orchestrators—so that it's musical, not just as a sound effect, but as lyricism, as harmony, as part of the main story. Trying to raise the percussive arts in my own small way to be an equal with these amazing composers, horn players, and pianists.

But you said it, vulnerability. My buddy Jim Yanda in Free Country, he always feels vulnerable. And I said, but that's what's so great about your playing. You do find yourself taking chances, and it isn't easy for self-acceptance. And yet when it's that human, when it's that sincere, when it's got that kind of earnest wisdom, real romanticism instead of some kind of schmaltzer looking back and, "Oh, isn't that cute?" No, you know, this is who he is. And I mean, this is what you try to strive for as an artist. Can I be completely translucent, completely vulnerable, and completely inspiring to others to be their best?

This band has done that for each of us. Hank Roberts or Drew Gress are on so many great things. I don't think you'll ever find them on anything better. Oh, it's different, but they play brilliantly, as does Jim with this band. Each of us managed to frame each other in our most flattering ways, and that doesn't always happen. You know, you try to put friends together, you try to put colleagues together, you try to—what's the sound going to sound like before we put it together? But you never really know until you do.

When Herb passed, and we all got the news, none of us felt like playing. And yet we knew we had to. This project had been postponed twice for various reasons. And so this was the time we were all here, and Herb would've wanted us to play. And then what came out has a vulnerability and a translucency, too. It isn't common. You know, we're all professionals. I'm going to bring my craft to bear and honor this composer, whether it's the guys in the room or whoever it is. And next thing you know, you're stripped down to your basic humanity, and that can be inspiring when it's right.

Lawrence: Correct me if I'm wrong—everybody's seeing the news, hearing the news, processing the news. So it was in the air. There was no conversation about bringing it overtly into the music.

Phil: No. It's interesting because it is pretty much the first thing that you talk about when you get off the bandstand. Once you get past, "I'm sorry I missed your second ending," you know? (laughter) That goes by pretty quickly. You're consumed with grief about Herb. You're really consumed by the disbelief. And then, I also had this great illusion, and I think many of us did when Obama was elected—I thought we'd finally matured as a country. And we watched what seems, in retrospect, to be a backlash.

What's interesting is that the vulnerability we talked about before can be beautiful or close you down artistically. I don't think we closed down. It was not an easy session. And all of a sudden, when I was producing at the end, what I heard instantly was, oh my God, the pathos in losing Herb and this election, this disbelief, is in the music. It's in every take. It might have been hinted at by the themes, the harmonies, or the title, but it's in there. Can you ask any more of artists? I mean, it's what we all dream of: being able to communicate time, emotions, and relevance. And it became clear to me—is this a failed record, or is this, oh, you actually have a work of art? So I took these, and I put them in what I thought was the only sequence that came to me pretty quickly. It's one of my superpowers, they say. And I noticed, you know, "Situation Ethnics," "Past Time," . . .

Lawrence: "Past Time" is a great track.

Phil: Right? And it's like we're in this time where every ethnicity, if you're not white, is under attack. And some people would have you look back to past times as if we had it together. And then I went on, and my working title for "Strands of Liberty" was just "Strands." And it became clear to me what it was about, because everybody has their own part. They're making up their melodic content. I only gave them the rhythms and the shape of their counterpoint. You can hear us trying to make sense of this. And because of how I structured it compositionally, there's Jim's cadenza toward the end, you can hear it just come apart. And that's how it feels when your liberties are questioned—you're losing control. And I couldn't believe our band's collective subconscious. It was as if it had been planned, and it was not, and yet there it was.

Lawrence: Can you tell me about the dialogue in the title "Liberty Now!" with Max Roach's "Freedom Now Suite"? Or maybe even I'll broaden the question—you add the exclamation point, which makes it a demand or a call, or it adds a . . .

Phil: Insist! We insist!

Lawrence: And you know, for the longest time, I had a hard time understanding the definitional difference between freedom and liberty. And it's only been very recently that I realized freedom is about your ability to do what you want, and that liberty is the responsible application of that freedom, living in or with freedom.

Phil: Well, it absolutely reflects on Max's work. The sixties were our last social revolution. And obviously, the raised brother fist, freedom now, Black power—all of those things that were part and parcel of the Black and the American experience in the sixties, and Max's incredible work—yeah, it's a landmark. It's one of those things that we as jazz musicians point to, let alone many other Americans. And so 'freedom now' didn't quite work, or 'we insist.' I had this tune, "Strands of Liberty." I look at this, and it's like, oh, it's Liberty Now! instead of 'Freedom Now' because, as you say, you're trying to parse what your rights are versus your action in public. And you know, your rights are supposed to stop at the next guy's nose, and boy, is that being questioned lately. We need liberty and everything that it implies because we seem to be giving it away. Some people don't realize what's going on, or they've been hoodwinked, and the rest of us are horrified that it can go this quickly.

Now the rules have changed. We grew up thinking and saying these things because we assumed we were born into the freedoms of speech, due process, and all of it. The rules, as of about nine months ago, were all but thrown out the window after 249 years of established tradition and norms, and it looks like it will only get worse unless something unforeseen happens. I don't think Superman's coming. And I don't think the rapture's coming either. It's like we are at this point, this Liberty Now! point.

We're going to have to find ways to rebuild an America that we can all be proud of. It's going to take a massive amount, and of course, it's above my pay grade to think I know what it's going to take. But I do know that we have to spread the good to start with, and that starts with being able to treat people in our family whom we don't agree with on religious or political grounds. We have to bring them back in and remind ourselves of what we all believe in, and that those things are more than our differences. We're not on opposite sides; we have differing opinions, but we share the middle. Because consensus is one of the things they're trying to say no longer exists. It isn't valuable anymore. And that's the cornerstone of democracy, finding consensus, that messy middle. It may not be efficient, but it keeps you from going too far, one side or the other.

Lawrence: I wanted to turn back to the record for a moment. Something that landed for me earlier today was the way you've constructed the album with the new material and then the second disc of what I would call curated material from throughout Free Country's catalog. You said earlier that one of your superpowers is in sequencing a record, and it seems you're bringing that to bear in this collection. What was going on there, and what were the through lines you were trying to bring to the surface for listeners?

Phil: Well, at first, there's just a simple craft thing. I have this album of new material, and I thought it was strong but also vulnerable. It alluded to the theme of Liberty Now!, but the band, over almost thirty years, had actually been hitting the nail on the head. We've always been a politically aware band. So I felt like, oh, a lot of people probably don't know the band's back catalog. I'm not going to put out a seven-disc set retrospective—that's just not going to get listened to. It was like, here's this album that alludes to Liberty Now! I can take one, two, or three tracks from each of our earlier records and make a compilation that underlines it.

That's a kind of liberty—we have the ability to do our own material, but we chiseled it from covers of Americana, from the Revolutionary War through the sixties, through today. This band didn't just blink and make one nice record. This is the fourth studio record and the fifth recording overall.

One reviewer was kind enough already to say that the album doesn't tell you what freedom is—it takes you through all these emotions and landscapes, just like real life. Freedom is not one thing, but it asks you to ask yourself, let alone your nation, what is liberty? What is freedom? What is it to be American?

We have to not just raise red signs but also pass on the good, build community, starting with your family and your neighbors, and hold your representatives' feet to the fire. And especially when truth and facts are under siege and being gaslit—most of those people know that they're lying. It's just—it's so overwhelming. It's such an overwhelming time. And how can we not stick our hands up and say something? And even when we weren't trying to say something, the whole band was relieved that we weren't tone deaf.

You know, I'm free-associating and, yeah, emotional venting. People would say, "I really can't talk about it. It just drives me crazy." And it's like most of us need to be able to talk about it so it doesn't become a pressure cooker that explodes. You have to let off steam and make sure the other person's okay, even though none of us are right now.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

Comments