Four decades after their formation in the famed industrial port town of Liverpool, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark remain one of electronic music's most vital and pioneering acts. Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys have sold over 40 million records with OMD, and Bauhaus Staircase, released in October 2023, finds the duo at their most politically engaged and sonically adventurous in years. It’s a continuation of the duo’s four-decade artistic dialogue and a sharp commentary on contemporary global upheaval.

During the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom, OMD frontman Andy McCluskey "rediscovered the creative power of total bloody boredom," writing the majority of what would become Bauhaus Staircase. The album takes its name from Oskar Schlemmer's 1932 painting Bauhaus Stairway, reflecting McCluskey's longstanding fascination with visual art and its role in political resistance. The record was inspired by world events and politics over the past couple of decades; songs like "Kleptocracy" take aim at contemporary autocratic leaders, while "Anthropocene" and "Evolution of Species" grapple with ecological crisis. Meanwhile, the messages are all delivered through OMD's signature blend of accessible melodies and sophisticated electronic arrangements.

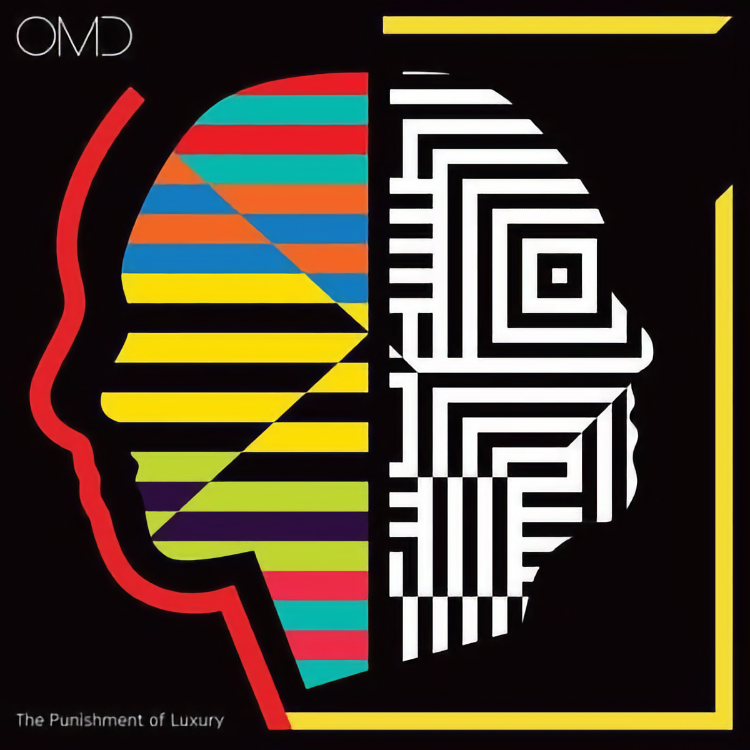

Since their 2006 reformation following a sixteen-year hiatus, OMD have established themselves as elder statesmen of electronic music while avoiding nostalgic victory laps. Their recent output—including 2010's History of Modern, 2013's English Electric, and 2017's The Punishment of Luxury—continues to propel the band forward in terms of sound, style, and ideas. "We've stopped being the forgotten band of the late seventies, eighties, and actually people say lots of nice things about us, like we're iconic and influential," McCluskey says. "And so finally, when we feel like we've got a place in the pantheon recognition, the last thing we want to do is make shit records."

I spoke with Andy McCluskey in late May 2024, just before the start of an extensive US tour that was unfortunately postponed for several months due to McCluskey’s requirement for knee surgery. McCluskey was was great spirits and a joy to talk to; there was much laughter even though we touched on some dark themes. We discussed his enduring creative partnership with Paul Humphreys, his thoughts on art as resistance to authoritarianism, the visual influences that continue to shape OMD's aesthetic, and how the band maintains relevance without sacrificing their distinctive sonic identity.

This conversation originally appeared on the Spotlight On podcast. You can listen to the entire chat in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Michael Donaldson: I’ll start with a little story. I was having an under-the-weather day and decided to watch two BBC documentaries back-to-back for a couple of hours worth of just sitting on the couch and enjoying myself. The first was Krautrock: The Rebirth of Germany, and it ends with Kraftwerk basically about to take over the world. As soon as that ended, I immediately started watching Synth Britannia, which begins with Kraftwerk playing Liverpool. So it was funny watching those together because it was like one documentary, sort of leading to where we are now.

Andy McCluskey: Well, I mean, essentially Krautrock led into the British synth explosion of the late seventies and early eighties. So they belong together.

Michael: Absolutely. And of course, you and Paul had the life-changing moment of seeing them in Liverpool.

Andy: Now, Paul wasn't allowed out by his mother. Paul was only fifteen.

Michael: Oh, so it was just you?

Andy: Yes. He's been so pissed off about that ever since. (laughter) And, effectively, it became a symbiotic relationship. I would go to Liverpool on Saturday morning with my paper round money and buy German imports, usually Kraftwerk, from a single rack of twelve-inch vinyl in Probe Records in Liverpool, which was the cool shop in the city. And then I would come back to where we lived in a suburb on the other side of the river. Paul, who was studying electronics and was an electronics geek, had built himself a stereo. I only had my mother's old sixties mono record player, but Paul had a stereo. So that was it. I had the records, he had the stereo. That was how we started listening to music together in his mum's house on a Saturday afternoon when she was at work.

Michael: What brought you to the German imports? How did you discover those at a young age?

Andy: I think like a lot of English teenagers in the seventies, I was looking for something new, looking for something different. I wanted something that was mine. I didn't want something that reflected what I already perceived as Anglo-American rock clichés. And of course, if you want to avoid Anglo-American rock clichés, then you discover Kraftwerk. And I heard "Autobahn" on the radio in the summer of 1975. It was everything I could possibly have wanted. It was new. It was different. It was musical to my ears. I thought it sounded fantastic, but it was completely different from everything else I'd ever heard before in my life. And so that was it. I then started going and buying their records. And then, when I had exhausted all the ones of theirs that I hadn’t previously purchased, I started buying Cluster, Neu!, Can, and all the various other German bands.

A certain type of teenager—I think it's different now because we're in the postmodern cultural world—but at the time, everything was perceived as linear. This is in fashion; therefore, that's out of fashion, and then the new fashion becomes old-fashioned and something new takes its place. I was looking to define myself by the three markers: music, haircut, and clothes. And Kraftwerk was my music. I liked a few other artists, but again, they were towards the more interesting end of the spectrum, including people like David Bowie, Roxy Music, Brian Eno, and the Velvet Underground. I mean, quite frankly, outside of my German bands and those ones I just mentioned, everything else was shit as far as I was concerned. (laughter)

Michael: Here's a dangerous question to ask someone from Liverpool: Do you think Kraftwerk are the most influential band?

Andy: Oh, I'm on record as saying that throughout the history of modern popular music post–Second World War, Kraftwerk are the most influential band in the world. The Beatles were very, very, very good songwriters. The path they took was quite remarkable. The changes in their music, from the early poppy days to the surrealist and acid later days, were remarkable. But, essentially, it was still variations on the Anglo-American blues-rock theme. Whereas Kraftwerk completely detonated all the clichés and did something totally new, as far as I'm concerned. And they heralded the advent of electronics in music, for better or for worse. The use of computers and digital technology. Kraftwerk are the most important band in the history of popular music.

Michael: So you've known Paul since he was seven, right? I'm just always fascinated by artists who have been in a working relationship with each other for that long, like for over fifty years, for you two. What is that like?

Andy: It is strange. I'm not close to any of the other friends I was at school with, except for Paul, because we started the band together. We started making music together when he was fifteen and I was sixteen. We're very different people. It's not always plain sailing. We've had our disagreements. And in fact, the band split up from 1990 to 2006.

When we fit together, we bring to the table what the other one doesn't have. Paul is an incredibly gifted musician. He's a brilliant writer of melodies. He also knows more about musical theory than I do, which is good. He's much more technically gifted and patient than I am. So he does the mixing. I, on the other hand, am full of intensity, full of ideas. I was going to do a fine art degree. He was going to do an electronics job. You know, there's the difference between the two of us, but it fits together. So I guess I was just blessed with the one great thing about Paul, which was fortunate for me—he’s a very creative musician, but he's not overly precious or egotistical. He would allow me to make whatever I wanted out of his ideas, as well as my ideas. It was a double blessing for me. We have joked as well that we are different characters, and two Pauls would get nothing done, and two Andys would kill each other. (laughter)

Michael: I've read your nicknames for each other, 'the butcher' and 'the surgeon.'

Andy: Yes, they hold up.

Recent examples of Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark's stylish design aesthetic.

Michael: So, the fine arts degree that you talked about. What was your focus within the visual arts?

Andy: By the time I got old enough to apply to university, it was more sculptural installations and conceptual. I was quite fortunate to just pass my A-level art, which is the end-of-school art exam. I wasn't particularly gifted at drawing. The painting I did used a lot of cut-up bits of magazine and newspaper, which they decided wasn't legally allowed. And I wrote my thesis piece about Dada in the style of Dadaism, which made it largely unreadable. So I scraped through with the lowest grade you can get. (laughter)

I got a place at Leeds to do sculpture. I chose Leeds because they had a recording studio. I could do audio installations as well. I took a gap year and that was when Paul and I started Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark in October 1978.

Michael: I love the fine arts thing because the visual is something that is a major part of the OMD aesthetic, right from the beginning. Is Paul part of that, or is that mostly your direction?

Andy: It's mostly mine, if I'm honest. I was working with Peter Saville, who, of course, was the art director at Factory Records and then became the art director at Dindisc, the subsidiary of Virgin that we signed to. Unbeknownst to us, Peter and ourselves ended up accidentally at the same record company after Factory, which was brilliant. Peter said he enjoyed working with me because I had a good understanding of art history. If he referenced futurists or Picasso or pop art, I knew what he was talking about, so I had the frame of reference. So generally, I would be more involved than Paul. And particularly recently, since we reformed, a lot of our music, titles, and themes have been influenced by artwork.

Michael: I remember, as a teenager, seeing records in the bins—especially any of the Peter Saville stuff, really—and I used to describe it as like receiving messages from outer space. Here I am, this kid in rural Louisiana, and I see these album designs, and I'm just like, "What is this?" Those were the wonderful days of buying records without hearing them, simply because of the cover.

Andy: The amazing thing was that I used to take the train to Liverpool and come back on the train, and I was sitting on the train with the record cover, opening it up, looking at the artwork, pulling out the inner sleeve, reading the lyrics, reading the song titles. And all of this in the hour to forty-five minutes before I got it on the turntable—it was like record sleeve foreplay, you know, before you got to the main event. (laughter) You'd already been absorbing the sleeve and getting yourself so excited by it.

Michael: Let’s talk about Bauhaus Staircase. This record's great, and I want to delve into what you mentioned earlier about art’s influence on the title and lyrics, and so on. I looked up a description of the Bauhaus Stairway painting by Oskar Schlemmer. There was a listing from The Guardian, and I'll just quote it because I thought this was interesting. It says, “[The painting looks] back at the Bauhaus as a utopia rooted in everyday life. These are ordinary modern young people. Hair and clothes in contemporary fashions, walking purposefully, intently. They believe in what they are doing. They have the rounded, simplified geometrical bodies that Schlemmer created in his ballets as they ascend to the higher state of modern marionettes."

Andy: Very good description.

Michael: One thing I find really great about that is that he's basically talking about people becoming robots. But, like Kraftwerk, it seems like a positive thing.

Andy: Obviously, Oskar Schlemmer, who painted the painting several years earlier, had done the incredible costumes for the Triadic Ballet. If you see them now, they're in the museum in Stuttgart, and they still look unbelievably crazy and futuristic, despite being over a hundred years old. I mean, essentially, what Schlemmer is trying to do there, for the sake of simplicity and clarity, he's trying to reduce forms down to simple shapes. It's reductive, but beautiful. In no way is he suggesting that people should be robots or that they should be minimized or reduced to robotic ways. As you say, they were actually young people who were exploring an interesting new future.

The amazing thing about the Bauhaus art school is that from 1919 to 1933, when it was closed down by the Nazis, it was an applied art school. It wasn't esoteric. It wasn't art for art's sake. It was the practical application of art for form, function, design, and architecture. And even so, the Nazis still shut it down. Totalitarian dictatorships are prone to do so with art because they're scared of it. They don't understand it. They fear that it might be saying something they don't understand about them. And often it is. Of course, I called it 'Staircase' because 'Stairway' was too soft. 'Staircase' had a nice punch to the rhythm of it. It needed that second syllable emphasizing.

Michael: I love the lyric, "I'm going to kick down fascist art." That might be my favorite lyric of the year.

Andy: That one just came out. Obviously, I was thinking about Bauhaus and I was thinking about Nazis, and you know what, the funny thing is, don't tell anybody, I have a soft spot for fascist propaganda art. The Russian posters and the Chinese...

Michael: Oh, I am a fan of Soviet-era graphic design.

Andy: Would I want to live in one of those totalitarian states? No, but my God, the art. It was stunningly powerful and beautiful, but of course, you had more people like Kazimir Malevich, who was one of the very first abstract artists, who had to go back to doing art that was recognizably, specifically figurative, because otherwise his art would have been banned by Stalin and the communists. So yeah, "I want to kick down fascist art" is also the idea of toppling statues, which we've seen several times over the last few centuries of those dictatorship statues being knocked down or put into statue parks to remind us of our history.

Michael: So does art help us maintain democracy, do you think?

Andy: Good question.

Michael: Well, I have this idea of creation as resistance. I tell this to a lot of my artist friends who are, understandably, upset about the state of this country and the world, and have horrible people living rent-free in their heads. They don't create because it's hard to find the mood. Which, again, is understandable, but my idea is that creation is inherently optimistic. You're making something for an audience that does not yet exist for that piece. It helps put one in the mindset that there is a future where someone enjoys your creation, and I see that as a resistance to fascism’s promotion of its inevitability. To paraphrase something I read from Brian Eno that really hit home, one responsibility of an artist, if they choose, is to envision worlds that we want to live in so that we can better imagine arriving there.

Andy: I think you have a strong case. I mean, how effective it is in terms of actually changing the world… I'm not sure that art deals hammer blows against problem situations. However, it is very good for reflecting, for engaging people to have an alternative mindset to what you might feel are situations that are not positive. That's obviously why I love Dada, because it was a response to the slaughter and horror of the First World War. What was scary was that some of the English vorticists and the Italian futurists were excited about warfare—they thought, "Oh yes, this is going to clean the slate, it's dramatic and powerful and shattered and strong and engineering." Of course, what came out of it was that Dada went, "If this is the future, if this is where technology leads us, we don't want any part of this. If this is what intelligent minds lead us to, then let's be stupid. Let's go boing boong chack and da da da!” It's as nonsensical as the sense that led us to the slaughter of the Great War.

Michael: As we get into this political arena, I have to remark that "Kleptocracy" is the happiest song about all these subjects I can imagine.

Andy: Did you ever hear "Enola Gay"? (laughter)

Michael: Exactly! There is a history that I’m sure you might be familiar with, dating back to “Enola Gay” and the concept of delivering serious messages through danceable songs. It's about not necessarily hiding the messages. It's almost like a movie that covers serious subjects, but does so in an entertaining way that not everyone picks up on, yet some people do, and it gets under their skin. Are you aiming for that tension with these songs?

Andy: There was no conscious endeavor when I wrote "Enola Gay" to sweeten the pill. If you try to be overly didactic, one, you end up making shit music because the lyrics don't rhyme properly or there's no melody or anything, and you're just beating people over the head with your words like a sermon. And secondly, yeah, it's a lot easier to get the medicine down if you put some sugar on it. But it honestly was not conscious. In fact, some people were quite horrified when "Enola Gay" was released. They were like, "Hang on, how can you have such a jaunty tune about something that was so terrible?" And I was like, "Yeah, I didn't intend it to be that way, but it kind of works." Because my fallback defense invariably was, "It's not as weird and fucked up as naming an airplane after your mother and then dropping an atom bomb and killing 150,000 people. That's fucked up."

I found, as I say, obvious moralizing can be very clunky and ineffective. I have often preferred to couch my feelings and ideas in metaphors, which sometimes can cloud them to the point where people don't understand what the hell I'm on about. And there are millions of people to this day who don't know what "Enola Gay" is about. But it was an opportunity, at least, to put the peg in the wall and then hang the ideas on it, and discuss them using the song as a kind of leader.

You can sit down with an idea about where you want to go and what you want to write. And when you're making a piece of art, it takes on its own life. Sometimes it goes off in a direction—you just go, "Holy shit, didn't expect it to go this way," or "This is not what I'd intended," or "This doesn't seem to be what I wanted to say, but you know what? It works better this way as a piece of music," so I have to go with the flow.

Michael: There’s another thing that I think you balance really well with Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark in 2024. Without naming names, many bands have been around for quite a while who have ‘modernized’ and no longer sound like themselves. They just become kind of homogeneous. Then you also have other bands that try too hard to sound like they did back then, which can make it sound very retro and nostalgic.

Andy: Yeah, it's like a pastiche tribute band of themselves.

Michael: Yes. And what I really love about what you and Paul are doing with this album is that you balance somehow in the middle to me. There are very few bands that have been around as long as you guys that effectively do that. I think that's very remarkable that it doesn't sound retro, but it sounds like OMD, if you catch what I'm saying.

Andy: Well, then again, we're hitting our mark. One, we were determined that if we were going to release new music, it would be good. It had to be strong lyrics, strong melodies, strong ideas. Both of us have continued to make music after the band split up, and we learned new studio and programming techniques. So we had a handle on how to make modern music. We weren't just locked off in our ivory tower back in 1983 or something. I think we were both able to employ those elements. But when you get to a certain age and you've made thirteen, fourteen albums, it's really hard to come up with new ideas. It's hard to come up with a melody you haven't done before, or a beat that doesn't go, "Oh, that's the same drum patterns, blah, blah." So you have to work hard at it. I like to think that, more than anything else, there's hard work that goes into it. It's not just like, "Yeah, yeah, we went in the studio and we threw together the first ten things that came and the good, the bad, the ugly, there it is. There's a new album." And it sounds like us because it is us.

As Paul likes to say, many bands release a new album because they need a logo for the new tour T-shirt. (laughter) It’s not because they want to make new records. They just need a new brand for this year's tour, you know? We are proud of the way we used to make music because when we started, we didn't know the rules. We weren't even consciously trying to break rules. We just didn't bloody know them, so we just did our own thing. "Oh, that sounds all right." And people subsequently said, "Did you realize that you were doing this and then you had a diminished fifth or something, and finally, you put the fifth note on it and completed the chord." I went, "Really? Okay. I had no fucking idea. Thanks for that." (laughter)

Michael: I think people appreciate and respect that mindset. I love this quote I saw from you, "Playing a hit single is not like going to the fucking dentist." (laughter)

Andy: I never understood why bands moan their ass off about, "Oh, I'm so bored of playing that song." Oh, what, the song that got you all the money? The song that's still played on the radio? The song that everybody loves, and you want not to play it, or even worse, do a stripped-down acoustic version at half speed? Have some fucking respect, you know?

Michael: You're finding a lot of younger, new fans when you play now, right?

Andy: We are. And it comes down to a couple of things. You know, we alluded to this earlier, this kind of postmodern era where nothing's in fashion, therefore nothing's out of fashion. And if you're considered to be seminal or iconic or just of value within a particular genre, then people will find you, and there's always a new generation of young people who get into electronic music because it's generally the most interesting music that's being made. There are only so many things you can do on a guitar, bass, and drums. Whereas computers, synthesizers, and samplers give you a much broader palette to explore. And I think that younger bands have credited us as being influential, so their fans have discovered us. People go down wormholes on YouTube and streaming, and, “If you like this, you'll like that." Yeah, it's fantastic to see the age demographic changing. It's wonderful.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments