For more than two decades, Justin Hicks has moved fluidly through the worlds of music, theater, performance, and sound art—sometimes as a singer-songwriter, sometimes as a conceptual sound-maker, always guided by an instinctive curiosity about voice as both a physical and emotional instrument. A longtime fixture of New York's experimental and interdisciplinary scenes, Hicks has worked across noise rock, multimedia performance, theatrical song cycles, and collaborative projects, including Grammy-winning work alongside Meshell Ndegeocello and Chris Bruce. He is also one-third of the HawtPlates, a theatrical vocal trio known for blending humor, intimacy, and compositional rigor.

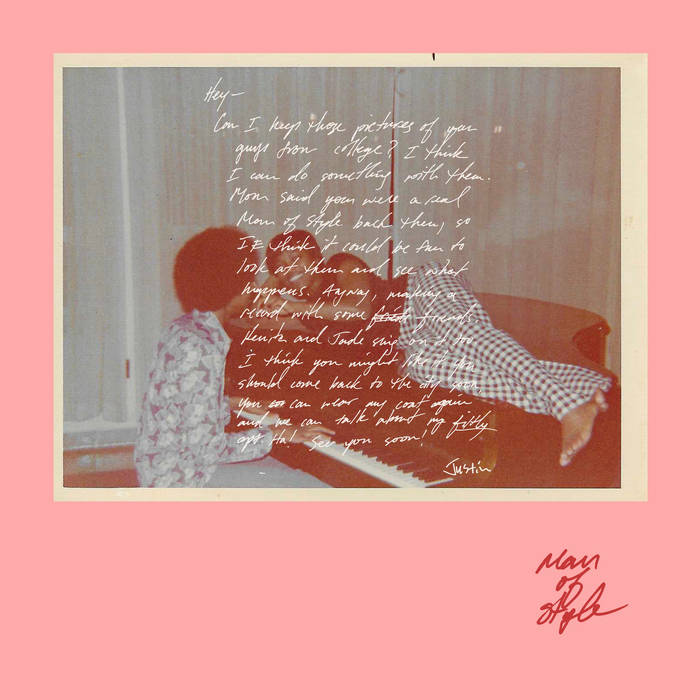

Despite this expansive résumé, Man of Style marks Hicks's first full-length release under his own name—a record that distills decades of lived experience into something deceptively simple and deeply personal. Recorded almost entirely over two days and shaped by long-standing creative relationships, the album explores voice as a site of discovery, tension, and tenderness. In this conversation, Hicks reflects on multiplicity, collaboration, ambiguity, and the quiet power of song as a way of meeting listeners where they are—and inviting them in.

Arina Korenyu: The press release describes Man of Style as a "biography of a voice exploring its own edge, and its beating heart." What does that phrase mean to you personally?

Justin Hicks: It's interesting. When I hear something like that, I think of it as a poetic way to describe the experience of listening. I can agree with parts of it.

In my own pursuits, whether I'm writing or singing, I'm definitely searching for discovery. And when we talk about voice, that's not just the physical voice—it's my heart, too. It's where the physical voice and my emotional and psychological voice meet, and that meeting point is where discovery can happen. That's the edge I would describe.

I think the edge depicted in that statement is similar: it's the place where the comfort and ease of the physical voice meet something less comfortable—something closer to heartbreak or falling apart. That kind of moment can feel startling, like standing on a precipice. There's an intensity to it that feels very alive.

Arina: The album was recorded almost entirely over two days. How did you cope with the speed and intensity of that process?

Justin: I'll say this first: the music on this record is very lived-in. Some of the songs were written nineteen or twenty years ago, while others came together just months before we stepped into the studio. That range reflects a long-held understanding of what I always wanted to do with certain songs, and how the newer ones grew out of that earlier body of work and fit alongside it.

The recording itself was intense in a very specific way. We were in the studio all day for two days straight, but I had my family around me. The way Meshell, Chris, and I work together is deeply family-oriented as well.

Meshell is especially good at knowing when the right people need to be in the room—and when they don't. Even if we were all there, she would gently say, "Okay, you need to step out for a few minutes while we do some things, and then you can come back." That kind of awareness made the process feel playful instead of pressured.

We self-produced the record, which meant there wasn't a single voice cracking the whip the whole time. We had clear goals and stuck to them. The time constraints were real, but the record itself is pretty minimal—there aren't many layers, voices, or instruments. I think the densest track might have ten layers at most.

There were a few moments of studio magic after the main sessions wrapped. Brandee Younger contributed to "Creator Plan Upstairs" while she was in LA. During mixing, we realized we might want to add just a little more in certain places. One of those additions was Levon Henry's horn arrangement on "Man of Style." Adding horns expanded the scale of the song and gave the album a more orchestral feel—it made everything feel bigger.

Other than those outside contributions and a few minor retakes—which we didn't really do much of—all the vocals and core performances were recorded in those two days. I wasn't on edge, worried things might fall apart—we just pulled it off.

That said, the engineer, Hector Castillo, probably had a different experience. I asked him for a quote about what it was like working together, and he joked that it felt like pulling teeth. That's often the engineer's reality. But Hector is a class act—he works incredibly hard and still manages to make everyone feel comfortable.

Arina: The title Man of Style is an acknowledgment of multiplicity. What aspects of your identity or artistry were you hoping to make room for within this project?

Justin: I've spent many years working across multimedia—art, theater, performance—often as a sound-making body or a sound-making brain. Against that backdrop, there's something beautifully simple about being a singer-songwriter: I have a song. I'm going to sing it. Someone might listen. It's clean and direct.

I remember opening for Meshell at Koko in London a couple of years ago. My banter was very straightforward. I said something like, "Hey, I'm Justin. You probably haven't seen me play before unless you've heard the Baldwin records or Omnichord." I mentioned that I was a chef for a while, that I was always playing music, that I'd been in bands, made noise rock, and collaborated on all kinds of projects over the years.

I told the audience that when I started moving more deeply into media projects and collaborative work, I thought the singer-songwriter part of me—the part that quietly guides all those other projects—might fade away. But I've come to realize that it never did. At the core, I'm still just someone who wants to sing songs. Even when I'm making experimental sound installations or working on something non-vocal, that's still who I am and who I'm presenting to the world.

The challenge is that in high-art environments, that simplicity—the grounded, colloquial nature of songs—can sometimes get overshadowed. The conceptual or formal elements can take precedence, and the song-self drifts into the background.

What I'm trying to do now is acknowledge and reacknowledge that part of myself, and even reintroduce it—to myself as much as to anyone else. The song-self never went away, but looking back while choosing tracks to record, I had this moment of recognition: Wow, this is who I am. This is who I was. And this is who I can be again. All of those things at once.

When I use the word 'style,' I don't necessarily mean 'adventurous,' but I do have a meandering ear and eye. I'm inspired by many different ways of making sound, singing, and expressing ideas. This record feels like a first pass—almost a brushing over of those influences. I think the next pass will go deeper, settling into one of those niches more fully.

Arina: You've mentioned being more interested in the work of singing than in the pleasure of it. How does that philosophy change the way you perform?

Justin: I feel that ebb and flow in the middle of a song all the time. Sometimes it's like: you're a singer—sing the heck out of this, really feel it through your voice. But other times, when you're saying something specific, you just have to say it.

A friend once told me, "Sometimes it just takes a singer to hear a word." He said that in relation to "Man of Style," specifically the line where I sing, "That's grief." He pointed out that every once in a while, that's what singing really is. It's not about wailing or making something beautiful—it's about clarity. A sad idea can land more clearly when a word is sung. It's drawn out just enough, highlighted in a way that makes you really hear it.

Another friend of mine, a wonderful theater artist, talks about 'embossing' words—how your sound can emboss a word and give it dimension. I love that way of thinking about singing.

Singing is obviously physical, so there's an awareness that you're doing work. But it's a strange kind of work—like patting your head and rubbing your stomach at the same time. You feel different every day, both physically and emotionally. For me, singing becomes a way to work with the same ingredients over and over and make something different each time.

Arina: You often allow lyrics to 'hover' rather than resolve. What draws you to that ambiguity?

Justin: I think that on Man of Style, there are moments that feel a little opaque or mysterious. But I do feel like I'm setting a stage that's very close to the emotion I'm experiencing—one that the listener might also be feeling, or that I want them to think through.

I'm not sure this is something to lock into completely, but I look at a lot of dance and used to be a huge admirer of Pina Bausch's work. She talked about how, in dance—especially her kind of work, which was often wordless—you can only indicate or suggest. You set the stage, and the audience has to meet you halfway.

That isn't entirely true with songs, because I'm using words. I'm singing something specific and trying to draw you in by stretching those words across notes. Still, I believe that what exists between the notes—along with a feeling or a loose statement—is often enough to pull someone inward, even toward themselves.

It's interesting how many different interpretations a single song can have. That's always true, but especially with my work. I think there's enough wiggle room, enough openness, for people to find themselves inside the song. There's space for the listener to be the song.

For me, songwriting is the clearest way I can communicate with a large group of people I don't know—people who may or may not love me, who may or may not like how I look, or any of that. When they're listening to the songs, none of that matters. Of course, there's a part of me that wants to be heard—but more than that, I want people to hear themselves in the work.

Arina: Your single "Poly" explores different approaches to love. What conversations do you hope "Poly" encourages among listeners?

Justin: It's kind of funny—some friends would say, "Hey, great track, I love it," and then a day later they'd check in like, "Are you okay? Are things alright with you and your wife? What's going on?"

My own life is pretty traditional. We're married with a child—a very straightforward setup. It's not especially unconventional, certainly not in the way people tend to imagine polyamory or nontraditional relationships.

What I love, though, is that the song opened up a conversation about something I don't have to be an expert in or personally live through. That lyric came from one of my closest friends. At the time, he was going through something very deep, and because we were close, we were all going through it with him. Situations like that can really populate your life in a different way. It's not just about you and your lovers—it involves friends, community, people who know what's happening. In his case, it wasn't always fully consensual, which made it even more complicated.

I think there's something meaningful about examining the inner workings of choices like that. There are so many ways to describe how people relate to one another—sexually, physically, emotionally. Some people are polyamorous in a physical sense, some emotionally, some both. My hope is that people can hear the song without judgment.

At some point in my life, I probably wasn't judgmental, but I knew it wasn't how I could live—it felt too complicated. At the same time, when we step outside tradition and really look at what works for people, it can be eye-opening. Growing up, my mom had a friend—someone I didn't know well, just saw around town—who had two husbands. She had a child with each of them, and the three of them built a house together. They were incredibly happy.

Arina: You've collaborated with Meshell Ndegeocello for years. What was different—or especially meaningful—about working with her and Chris Bruce on your own debut?

Justin: It feels like the culmination of a long period of working together. Over the last ten years, we have been constantly collaborating—on Meshell's releases, on shared projects, and on side things that grew organically over time. And now, especially since I'm not touring with them as much anymore—we still have some Baldwin one-offs coming up—it feels like the collaboration is shifting into a new phase. An exciting one.

Meshell is producing a lot right now, and people are asking her to produce their records. To be part of that larger trajectory—to be included in that moment of her career—feels like a real honor.

And Chris—Chris is a force. He's the deep cut behind so much music that people love, especially Meshell's. Chris is the unseen connective tissue in a lot of people's favorite records.

We all came together originally around one very specific project with a strong literary core. It's rare to play the same songs with people for a decade and still discover new ways to feel them, hear them, and shape them—to keep wanting to return to that place.

This record isn't a document of that history—it's very much my record—but it does mark a moment where Chris and Meshell are really flexing their producer muscles. The same goes for me. We truly collaborated on the production. I brought in demos and said, "This is the map—you can follow it or diverge from it—but we need to find what makes sense to focus on in these two days." We spent weeks narrowing down the track list from a huge pool of songs I kept sending them, figuring out what belonged on the record.

That process deepened our collaboration and added new nuance to how we communicate. It's shifted our relationship. I feel more connected to them now. I don't feel like the guppy in the room anymore—I feel like a more formidable songwriting and producing force. That confidence comes from being around peers who are experienced, tested, and deeply skilled.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmDee Dee McNeil

The TonearmDee Dee McNeil

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments