Ahoy, fellow newsletter aficionado! Welcome to this week's Talk Of The Tonearm newsletter, where I, your pal Michael, enthusiastically guide you through some of our recent stories and a whole slew of snazzy recommendations. More rock, less talk—let's get on with it:

Queued Up

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

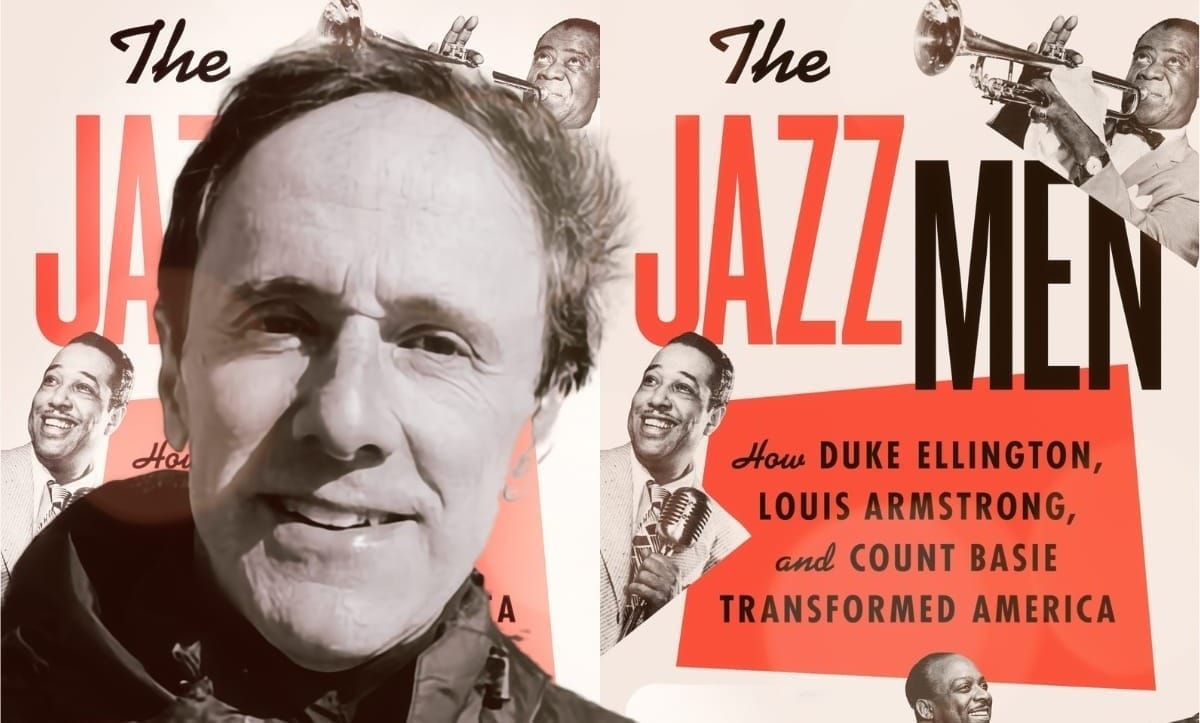

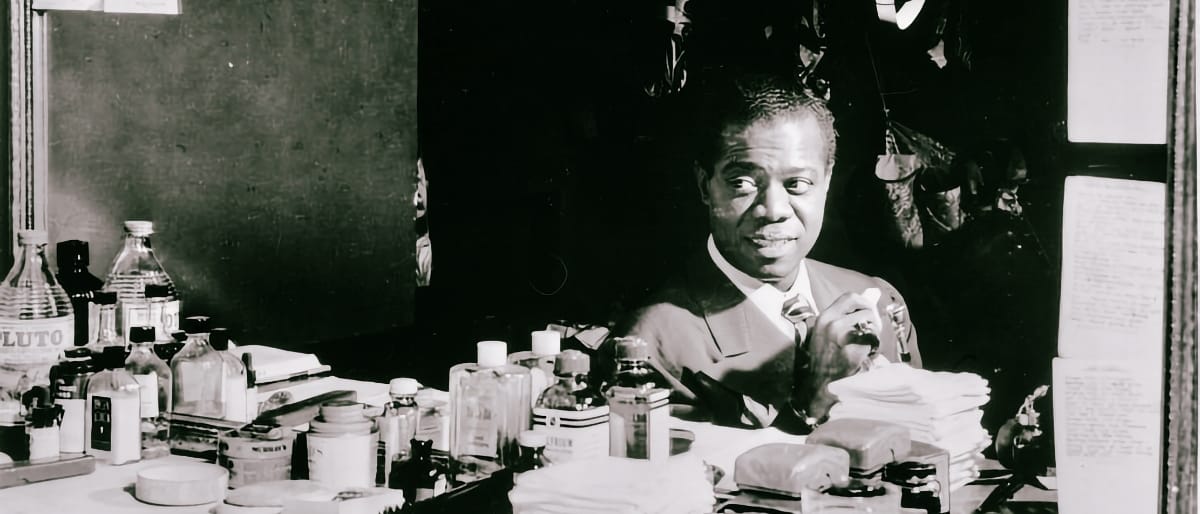

Among its many fascinating anecdotes, Larry Tye's The Jazzmen relates the story of a politically consequential hotel room interview with Louis Armstrong. A young journalist knocked on Armstrong's door in 1957, requesting a comment about the Little Rock school integration crisis. Armstrong's impassioned response reverberated from the White House to the Kremlin and may have changed the course of civil rights history. Despite his carefully maintained image as an unopinionated ambassador of American music, Armstrong pointedly called Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus an "uneducated plowboy" (though his exact words were not appropriate for family-read newspapers) and President Eisenhower "gutless."

The timing could not have been worse for American foreign policy. Armstrong was scheduled for a Soviet tour as part of the State Department's jazz diplomacy program, designed to counter Communist propaganda about American racism. Oh, the irony—the US government was using Black artists to promote American freedom while those same artists were denied basic rights at home. Armstrong turned this 'jazz diplomacy' against itself as his criticism exposed this hypocrisy on a global stage. Furthermore, Eisenhower genuinely loved Armstrong's music and had hosted him at the White House, making the betrayal both political and personal.

What made Armstrong's statement especially powerful was how it shattered expectations. For years, younger civil rights activists had dismissed Armstrong as an accommodationist, while white audiences cherished his playful persona. Armstrong seemed trapped in a performance of docility, and that was eating away at him. When he finally broke character, commenting on Little Rock, Armstrong's words sent shock waves across the nation.

Federal troops arrived in Little Rock days later. Tye can't prove direct causation, but he believes the president was responding, at least in part, to being called out by the man he considered America's greatest musical hero. Budding celebrity activists take note (and I wish they would): criticism is most effective when it feels like betrayal, especially if your loyalty wasn't previously questioned.

Playback: That Obscure Object — Marko Ciciliani's Speculative Sound Stories → Composer Marko Ciciliani rewrites history to expose gendered assumptions embedded in musical culture, thus exercising political critique through speculative storytelling. Like Armstrong's provocative remarks, Ciciliani's work challenges dominant narratives, though his approach uses artistic fiction rather than direct political statement.

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

Darol Anger enjoys nerdy conversations at the merchandise table. "I get off the stage and can go over to the merch table, and I can talk about fiddling," he says. "Somebody comes up and asks about playing in a funny key, or how you get your fourth finger working properly." For Anger, this is just an aspect of the community that gathers around his music, one that evaporates the relationship between performer and audience. "The people that are on stage doing the stuff are just sort of doing R&D for the audience," he observes about bluegrass and acoustic string music. "We're just actually doing research and development for them—'Here's something you might want to try, try playing this with your group.'"

Anger analogizes this with one of "the great American hobbies": car clubs. "It's like car clubs where people who work on cars also drive cars," he explains. "Bluegrass is like any kind of scene where all the people involved are kind of doing it at some level." Consider the early days of hip-hop, where block party audiences regularly grabbed the microphone, becoming participants in real time, or rave culture, where DJ, producer, and dancer were often one and the same. Then there's the Grateful Dead, who encouraged tape trading and turned their audience into an unofficial archival network. Deadheads documented, categorized, and redistributed shows, creating value beyond the band's official releases.

This might explain why certain musical communities stick around while others fade away. "Most of the people who like this and are fans of the people who play this kind of music are musicians," Anger says. "They play an instrument, or they sing, or they do something." This goes against the hero worship that dominates mainstream music culture, instead cultivating the sharing of knowledge and collaborative elevation. Anger's latest album tested these community bonds; the recording sessions featured twenty-four musicians maintaining collaborative spirit despite physical separation. "I think everybody was just happy to have something to do, something to play with," he says. We learn that even in isolation we can forge strong connections.

Playback: Buzzing with Zen — Steve Holtje's Improvisational Honeymoon → Steve Holtje finds Brooklyn's Bushwick/Ridgewood noise scene supportive in a way that's similar to Anger's description of bluegrass culture. Both offer an environment where mutual support flourishes and competitive hierarchies are distrusted. Exploration is valued over technical prowess, resulting in what Holtje calls the most open and loving musical community he's encountered.

The TonearmDee Dee McNeil

The TonearmDee Dee McNeil

In our interview with drummer Nate Smith, he repeatedly sings the praises of Prince's Sign of the Times over the more commercially recognized Purple Rain. Smith says the catalyst of his latest album, LIVE-ACTION, is the 1987 double album's blend of psychedelic rock, funk, and jazz. There's a genre-ambiguity throughout Smith's album—Lionel Loueke's West African vocals merge with JSWISS's hip-hop vernacular and Lalah Hathaway's sublime pop music tribute. Prince's Paisley Park sessions taught artists like Smith how the studio could be a genre-agnostic workshop where experimentation supported emotional truth.

There's a cultural lineage from Prince through D'Angelo's Voodoo sessions to Flying Lotus's cosmic hip-hop, Thundercat's liquid bass work, and contemporary artists like Solange and Frank Ocean. They all seem to embrace Prince's psychedelic production ethos, which amplified R&B's capacity for vulnerability rather than diluting its directness. In other words, sonic flash doesn't have to detract from soulfulness. Sign of the Times confirms that Black artistic expression could be experimental and uncompromising without sacrificing its emotional core.

Nate Smith's idea that "there's space for everybody to play, but it still sounds cohesive" echoes Prince's vision of musical utopia. Smith is treating creativity as more than a commercial project, so his identification with Sign of the Times makes perfect sense. The album advocates for artistic ambition over hit-making, and for the long view that Prince's masterpiece provides: creativity thrives when genres collide and transform.

Playback: Rhythm and Echo — Adrian Sherwood and Style Scott's Dub Revolution → Adrian Sherwood thinks of the mixing desk as "an instrument of time and space,” which sounds like something Prince would say. And Sherwood's application of dub production techniques across genres follows in Prince's spirit of style-blending as creative innovation.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Adam Weinert reconstructed Ted Shawn's lost choreography through agricultural labor, tapping into a radical tradition of American artists using manual work in their creative practices. Shawn insisted that his all-male dance company spend hours each day working the fields at Jacob's Pillow, setting a philosophical foundation for American art. The 1930s brought widespread cultural anxiety about authenticity as the Depression shattered faith in industrial progress and intellectuals questioned whether American culture was far removed from its roots. Thus, Shawn's rejection of ballet as a "bourgeois, Eurocentric tradition" was aesthetic and political. He grounded his art directly in American soil by having his dancers clear fields and tend crops.

Shawn wasn't alone in his thinking. Black Mountain College adopted similar ideas, requiring students such as future collaborators Merce Cunningham and John Cage to participate in farm work as part of their artistic education. Cunningham later developed Shawn's ideas through his focus on everyday movement and ordinary gesture. Martha Graham, who studied with Shawn, maintained his emphasis on the body's connection to earth through her revolutionary "contraction and release" technique that pulled dancers down toward the floor. Both Graham and Cunningham rejected the theatrical while connecting their art to lived experience, and the farm-as-artistic-field-work model reappeared throughout American cultural history, from 1960s communes to contemporary artist-farmer movements.

Weinert's research brought him to the same soil that Shawn's dancers had worked. His insight that he "should get into some of this farm work to try to embody what they had embodied" implies that accessing these traditions requires physical experience. Weinert is now an arts administrator at Hudson Hall and carries on this notion of place-based artistic practice. His concept of the "terroir of the performing arts" treats creative work like wine, where the final product bears the characteristics of its geography and community.

Playback: The Beautiful Debris of Sam Sadigursky's 'The Solomon Diaries → Composer Sam Sadigursky's work looks to the ruins of Catskills resorts as inspiration, using these locations as the bedrock for his work. Likewise, the handwritten folk tune collections inherited from his Soviet émigré father are a different kind of "terroir," one where culture, tied to specific places and communities, passes through generations.

The Hit Parade

- This week, the Spotlight On podcast features a delightfully fun and casual conversation with songwriter/composer Robin Holcomb and cellist Peggy Lee, recorded with host LP in-person at Seattle’s The Royal Room. It’s a musical Pacific Northwest meeting of the minds, and you’re welcome to eavesdrop.

- I had asked Ethan Miller (he of Orcutt Shelley Miller) for something he loves, and he just asked me to plug the debut album from Julie Beth Napolin, titled Only the Void Stands Between Us and released on Miller’s Silver Current Records. OK, I’m listening now and am happy to report that it’s indeed worthy of a plug. The album is firmly in that psych-folk Velvet Underground kind of mode with its “ethereal, buzzing acoustic riffs, helix of resonant drones, and vocal delivery that often sounds like an ancient form of prayer." Yep!

- I’ve also had Lucretia Dalt’s new one, A Danger to Ourselves, resonating in my headphones all week. And in the headphones is where this one performs best: Dalt’s twisted vocal layers, the tuned percussion, and strange little details are things you might miss out on otherwise. I’ve been a longtime fan of Dalt’s exotica-tinged, Spanish-infused, electronic-hybrid output for a while, so it’s nice to see this album getting her some extra attention. And Dalt and David Sylvian are apparently now a ‘team’ which is both incredible and not entirely unexpected.

- But what if you want to listen to ‘the classics’ but you’ve got a bit of decision paralysis holding you back? How about taking the 1001 Albums Generator for a spin? Sign up on the site, and each morning you’ll be assigned a random album from the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die for your listening pleasure and/or education. You’re also prompted to write something about and rate each album, which helps push this beyond casual listening. I love stuff like this.

- Short Bits: Here’s a gift link to the NY Times obit for the incredible Brazilian composer and musician Hermeto Pascoal. What a life. • NPR fondly recalls Dee Snider’s testimony before Congress against the PMRC as we approach the event’s 40th anniversary. • A back-handed compliment all-timer. • A brand new Tortoise song, album imminent. • And, finally, there might be a few of you out there who are excited to hear about this Swell Maps release.

Well, Hello Dolly!

Sign up to get Talk Of The Tonearm in your inbox every Sunday, no questions asked—I mean, except for 'what's your email address?'

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Run-Out Groove

This one's shorter than usual as I've got a lot to do and would like to enjoy the beautiful weather for at least five minutes today. Oh, and yes, 'Surface Noise' is missing—thanks for noticing, regular reader. I'm stealing it for something else, and, to be honest, 'Queued Up' makes more sense for that section anyway. Huzzah!

Thank you for reading and, as we newsletter people like to say, please forward this email to a friend or five who you think might enjoy it. You're also welcome to post the 'View in browser' link at the top all over the friggin' place. That's a big help as we expand our sprawling media empire (sic). And what do you think? Please respond to this email with your thoughts and comments, or contact us here. Our CEO (sic) will get back to you straight away.

Have a wonderful week. It's extra weird out there lately, so don't dawdle. Or do dawdle—sometimes dawdling is the best we can do, and that's okay. I appreciate you, dear reader, and I will see you again here next week. 🚀

Comments