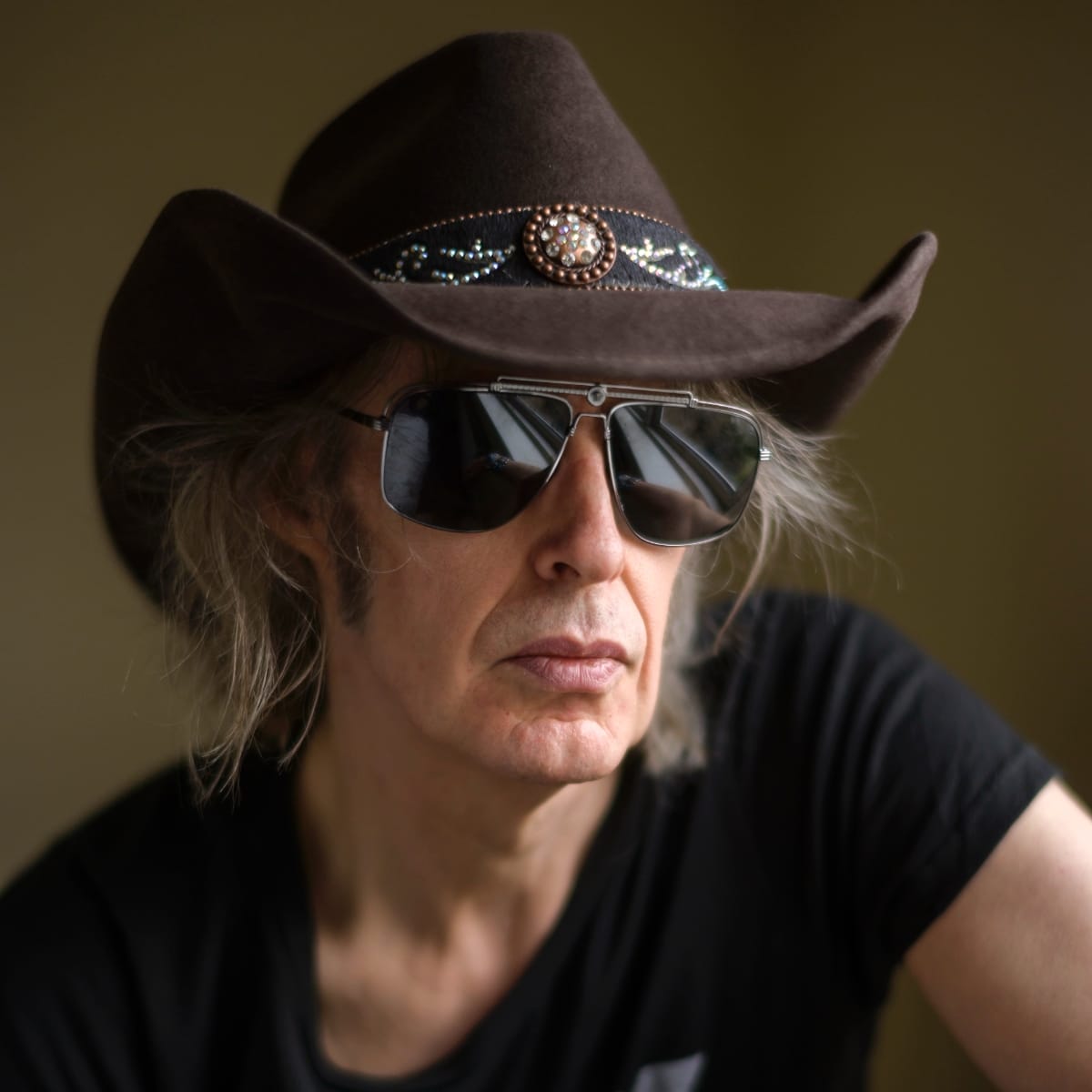

In the four decades since Mike Scott first formed The Waterboys in 1983, the Scottish musician has proven himself a restless creative force. From the majestic 'Big Music' that defined early albums like This Is The Sea with its enduring hit "The Whole of the Moon," through Celtic-influenced folk revivals on Fisherman's Blues, to ambitious literary adaptations like 2011's An Appointment With Mr. Yeats, Scott has continually reinvented The Waterboys while adamantly maintaining his artistic vision.

The band's discography reflects Scott's expansive musical interests and a journey that has encompassed rock, folk, soul, and spoken word, always centered on a poetic sensibility and an insatiable curiosity. Scott has remained the band's only constant member, describing The Waterboys as "myself and whoever are my current traveling musical companions." (Ed: That's a lot more eloquent than how Mark E. Smith described The Fall.)

Now, Scott and his latest incarnation of The Waterboys have created Life, Death, and Dennis Hopper, a sprawling 25-track concept album that chronicles the extraordinary life of the iconic American actor, filmmaker, photographer, and countercultural figure. What began as a chance encounter with Hopper's photography exhibition, “The Lost Album,” at a London gallery in 2014, blossomed into a four-year creative odyssey for Scott, who became fascinated with Hopper’s artistic output and the actor’s life as a mirror reflecting the cultural transformations of late 20th-century America.

The album's scope is as vast as its subject. Scott documents Hopper from his childhood in Kansas through his breakout in Rebel Without a Cause alongside James Dean, his revolutionary directorial triumph with Easy Rider, his lost decade of addiction, and his eventual redemption as a respected Hollywood character actor. Scott approached the project with characteristic thoroughness, including instrumentals for each of Hopper's five wives and recruiting an impressive roster of collaborators, including Bruce Springsteen, Fiona Apple, Steve Earle, and emerging vocalist Barny Fletcher. Scott calls the result "the whole strange adventure of being a human soul on planet earth."

Alongside Scott's core Waterboys lineup—featuring Brother Paul on keyboards, "Famous James" Hallawell on piano and guitar, Aongus Ralston on bass, and Eamon "Rimshot" Ferris on drums—the album moves through various musical styles that subtly reflect the eras of Hopper's life. From the Americana-tinged opener "Kansas" (sung by Steve Earle) to the psychedelic sounds of "The Tourist" chronicling Hopper's photography in the Sixties, to the raw post-punk energy of "Ten Years Gone" reflecting his lost decade, the music provides historical context while remaining quintessentially Waterboys throughout.

We were honored to have Mike Scott as a recent guest on the Spotlight On podcast. In his revealing conversation with host Lawrence Peryer, Scott discussed the creative universe he has built around Hopper’s life, drawing parallels between his own artistic struggles and Hopper’s, comparing the experience of making Fisherman's Blues to Hopper’s The Last Movie. Scott also comments on the cyclical nature of artistic success and failure, the creative resilience that defined Hopper's career, and the spiritual dimensions that emerge when examining a life devoted to art in all its expressions.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, flow, and clarity.

Inhabiting a Role

Lawrence Peryer: I've been immersed in the world of Mike Scott and Dennis Hopper for the last few days. But you've been immersed in that world for the better part of a decade to one degree or another.

Mike Scott: Well, four years making the record certainly.

Lawrence: It almost seems like a method acting approach to making music. I'm curious about your channeling of another personality that way, and if it's different from how you usually write. I understand it's story-driven music, or you're telling tales and songs, so there's always an element of character, but what's it like to have an extended narrative like that?

Mike: It was wonderful to work on it, and it was such a lot of fun. Inhabiting a role while recording is something I’ve been doing more of and becoming very comfortable with, and I do a character on half a dozen of the tracks on the Dennis album. I think there are a couple of spoken bits on “Memories of Monterey." I'm the character in the Pathè Movie Tour news character in "Transcendental Brewing Blues." I'm the “Freaks On Wheels” guy. I'm Dennis a couple of times as well, and in "Frank," the track with the f-word as almost the sole lyric, it's me being Dennis, being Frank, the character in Blue Velvet, so it's a double act.

Lawrence: I’d like to know the genesis of your sort of, for lack of a better way to say it, your fascination with Dennis.

Mike: Well, I was in London, it was in 2014. I was on Savile Row, a street renowned for its tailors. And I was probably browsing through shirts, jackets, or something. When I reached the bottom of Savile Row, I came across a large art gallery called the Royal Academy. As I passed its window, I saw a poster for something called "The Lost Album" by Dennis Hopper.

And I was doubly confused because "Lost Album" sounded like a record album. And then there was Dennis Hopper, who wasn’t a musician; yet, this was an art gallery, so was he a painter? I walked in to find out, and, of course, it was an exhibition of Dennis’s photography. I had no idea that he was a photographer, let alone a great one.

And so I walked around the exhibition, soaking up the hundreds of beautiful black and white images that captured the spirit, events, and personalities of the 1960s, particularly in California. And I was drawn into Dennis's world. Those photographs found me from a completely fresh perspective.

I had no preconceptions about Dennis's photography. If I'd even planned to go, I might have had some expectations, but because I just walked in off the street, the photographs just hit me, bang, bang, bang. I became fascinated by Dennis, and there was something about his photography—the way he seemed to capture people's spirits and moments in time.

And also, why was it only 1961 to 1967? Why were there no photographs after 1967? It was fascinating. So I started reading biographies of Dennis and I bought myself a book called Dennis Hopper Interviews, which went right through his career and quickly, I learned all about Dennis's life and of course what I began to realize was how present he was at so many hinge moments in the development of popular and youth culture from its Big Bang, really, when he acted with James Dean in Rebel without a Cause, right through the fifties, sixties, and seventies.

Lawrence: Something that is very striking to me about the project is that, as a listener, if you had no context and just put it on, it’s like, ‘ Man, what a vital, vibrant rock and roll album for the 21st century. ‘ We don't get a lot of those anymore. However, there’s also an adult element to it. It's so musically adventurous. But where it's relevant to the life of Hopper, I think, is that there's a real parallel in the music. Did you sit down and make a map? Could you discuss the process a bit, in comparison to its organic nature?

Mike: My interest in Dennis developed as I read the various biographies, and as I began to piece together the whole picture of his life and his career.

And I found that I liked him. He could do really stupid things, and sometimes success went to his head and he would make all these ridiculous quotes, like, “We're gonna be the most creative generation in 2000 years." But he was lovable even at his most hubristic. So I felt I liked him. And it was natural for me to write a song about him because I often write songs about people that I like and people who I find fascinating. You know, I wrote a song about Hank Williams. I've got a song about Elvis.

And so it was easy to write a song about Dennis, and terrific fun. It came out in an album about five years ago. It was just called "Dennis Hopper." And every line rhymed with the word 'Hopper,' which was a nice songwriting challenge. But I wasn't finished clearly, and I don't know how much of the story you know, but my band members recorded some instrumentals and sent them to me in a zip folder with a note saying, “Can you put lyrics to these?” As I was thinking about Dennis and reading about Dennis, the lyrics came out as Dennis Hopper biographical histories, and I think the first one that came out in that way was "Hopper's on Top" when he's at his peak, when he's just at the success with Easy Rider.

And then another one happened and another one happened, and suddenly I'm looking at these songs, thinking, what am I gonna do with these? In comic books, when you get the light bulb above the head and it switches on, at some point, I must have had that moment and realized it's the album of Dennis Hopper's life story. After that, it was a case of just identifying which episodes belonged in the story. What episodes did I have to document to provide a cohesive account of his, not just his life, but his presence in modern culture?

The Fool's Game

Lawrence: You're telling these different stories across time. It lends to that feeling for me, as a listener, of something big and sprawling. I thought of Physical Graffiti—it covers so much ground, with some songs having this massive grandeur, and others being just little interludes. It's really in the fine tradition of the ambitious rock album.

Mike: I think if there's any precedent that influenced me in that way, I don't mean musically influenced, but in terms of the scope of it would've been Tommy and Quadrophenia by the Who.

Lawrence: Yes.

Mike: Because you get these big, massive songs like "See Me, Feel Me" or "Amazing Journey." But you also get "Tommy's Holiday Camp" or in Quadrophenia, you get "Bellboy" and I love that.

Lawrence: It seemed like a real opportunity for you to almost like survey your musical life as well. I mean, there are so many of those elements there. There's the bombast of the Who, I can hear the Kinks in there. And then you have some almost like show music. And how important is that sort of stylistic panoply to you?

Mike: Well, I like to be free to do whatever kind of music I want. In the 1980s, I battled with record companies and managers and even rock journalists and fans to get the right to make the music I wanted to make, to step out of making what people called ‘big music,’ such as “The Whole of the Moon" and This is the Sea. I wanted to explore roots music, such as Americana, country and western music, or Celtic music. And I feel I won the right to do that and to play any kind of music I want. And anytime people try and put the Waterboys in a box, it's kind of a fool's game. It can't be done. And I've always loved artists like Neil Young or The Beatles or Dylan, who would do the same thing, play whatever kind of music they want.

So it's not so much a new thing for me to do this, but certainly the Hopper record with its span over four decades chronologically in the story, allows for that and allowed me to have a sort of grand slam of all different musical styles, even though I didn't set out to do that. But I noticed quite early on that each song seemed to be taking on the character of the music that was popular at the time of the lyric that I was writing. So, when I’m writing about Dennis in 1970, making The Last Movie down in Peru, I thought it sounded kind of like The Who. When the guitar comes in, it's very Townshend-ian. And once I noticed that, I didn't set out to do it. I didn't think, "Oh, I'm gonna make it sound like the Who here." It just happened. But after I noticed it, I didn't mess with it. I allowed it to be, and I think that was important.

Lawrence: What’s interesting, as I've learned more about this project, is what I'll call the creative universe you've built around it with the sleeve notes and the short film. It's a wonderful experience to move through all that and to hear you tell the tales and anecdotes. I’m curious about some of the personal bits about Hopper's struggles around The Last Movie and some of the parallels you've drawn with different parts in your career, specifically around Fisherman's Blues. What was going on for you there?

Mike: I should say that I don't think Dennis Hopper and I were similar as characters at all—very, very different personalities. But there were things that happened in his life that reminded me of myself, and one was when he made The Last Movie, he got bogged down in the editing. He just had his first success, and it was as if he couldn't do anything wrong, yet he got completely dug in and lost his perspective.

That reminds me of when I made Fisherman’s Blues in the mid-to-late 1980s. I had my first little beginnings of success with This is the Sea, not comparable to Easy Rider, but in my world, that was a breakthrough for me. I won the right with the record company to do whatever I wanted for the next record. And, much like Dennis going off to Peru, I went off to Ireland and made this epic record. And then I got bogged down and lost perspective on finishing it. So when I read about Dennis in The Last Movie, I thought, well, it's like me and Fisherman's Blues.

So that was part of it. And then, when it went wrong for Dennis and he released The Last Movie, the film studio pulled out because they thought it was a failed movie, and it flopped. As a result, Dennis blamed the movie business for some time. That reminded me of me as well, not with Fisherman's Blues, but when I was very young.

I had a record deal with Virgin Records in London. We recorded an album, but they didn't want to release it. And I was so upset about that and I blamed the music business for that for about six months of my life with "fucking music business, this fucking music business." Then I realized, “Wait a minute.” The record wasn't very good. It was partly my fault. I kept doing what the producer told me I shouldn't do. So I grew out of it in the same way that Dennis did, but it reminded me of myself, and I thought, "God, I know how that feels." I know how Dennis felt when that happened.

Lawrence: There's something almost universal there, in terms of the artist who has the big success and has earned the right to do it their way. It seems like it’s inevitable when given that freedom, and you see it in film and music, and I'm sure in other fields. What is it about the artistic temperament?

Mike: I think more than anything else is the lack of people telling them "no." I know from my own situation that when I made the first few Waterboys records, I had a relationship with the record company that was very fractious. We were always arguing. We would never agree on which songs should be included in the album and how they should be finished.

But out of the fighting, the albums emerged, and by arguing with me, the record company showed me what I didn’t want, which revealed to me what I did want. So, it was a very productive process. When that tension is removed, and the artist suddenly has a hundred percent right to do whatever they want, with no guardrails or limitations, then the artist loses their frame of reference.

I'm 66 years old now, and when I make records, there isn't any record company that's gonna tell me what to do and what not to do. But because I'm older and experienced, I know how to maintain perspective, and I know when I need to ask people what they think. I'll send the work in progress to a very experienced former A&R man, which I did with the Dennis Hopper record, in fact. And I'll take on board what I'm told.

I have these tools for maintaining perspective, but when I was in my mid-twenties, making Fisherman’s Blues, I didn’t have any of them. And it was almost a matter of self-identification that I didn't ask people, and that I found a way to make all my own decisions. Of course, without any limitations, I quickly ran into trouble. And I think that's definitely what happened with Dennis with The Last Movie.

History from a Child's Perspective

Lawrence: There's a certain romanticism of that era that Hopper's adult life encompasses, but there's certainly a dark underbelly through a lot of it. Whether it's the hippie era turning into the hard drug era or just the way youth culture evolved into—whatever it is we're still dealing with now, as the boomers maintain their places on the stage. What perspective did you arrive at about that era, and has that perspective evolved as you've immersed yourself in so much of the history and the tales?

Mike: It was something I was already immersed in. I'm fascinated by the counterculture and the development of popular culture. I was a child in the sixties, and I remember all the events from a child’s perspective. I remember "All You Need Is Love" on the global telecast the night it happened. And I remember Magical Mystery Tour on the TV, the night that it was broadcast, "Hey, Jude," on the TV, the Rolling Stones playing "Jumping Jack Flash" on the television.

For me, the changes in consciousness and political awareness in the 1960s are something very precious. Personal freedoms that were gained, for example, for homosexuals, Black people, or women. And those are crucial, crucial advancements. And building on previous advancements, like political liberation, when everybody got the vote or the freedom of thought and spirituality that's been part of the 20th century.

You know, when people were born in the 1890s or early 1900s, they did what their parents did, and they worshiped like their parents did, and they were ostracized if they went against that. But we now have this spiritual independence and freedom to be who we want to be, and that's a wonderful advance or evolution that was made possible by human endeavor in the 20th century. And there are those now who would take that away, and they won't succeed because you can't put toothpaste back in the tube. So, I have been interested in these developments and the counterculture and popular culture as a vehicle for human freedom for a long time.

I also see that the hippie generation had a lot of flaws built into it. There was a lot of misogyny in that generation. They weren't exactly good about treating women well. Also, in spirituality, it’s essential to intentionally integrate spiritual experiences when they occur. Someone once said that for every year you spend learning spiritually, you have to spend seven years integrating what you've learned. The hippie generation learned a lot spiritually, very, very quickly from about 1965 to 1969 through acid and consciousness-enhancing drugs and communal mass experience that was incredibly powerful for them. But because it had been arrived at in large part through drug means and drugs that perhaps should have been taken in a reverent way, but which were mainly taken recreationally, they didn't integrate the wisdom. And so it quickly flipped to a much darker expression.

And that's how you get that great quote of David Crosby's: "We were all gonna hold hands and sing to God. And we ended up with guns outside the drug dealer's door." The darkness of the sixties, the late sixties, and Manson and Altamont and all that. But I don’t think that undoes the greater gains of that period, including the gains in consciousness and personal freedom. And I think we're still learning from that time and still exploring those breaking of limitations. It's in the information technology; it’s in the information-rich, information-saturated society we're in now.

Lawrence: We're sort of in real-time living with the repercussions of the speed of technological transformation, and it reminds me a lot of what you just said about that '65 to '69 period, which is our transformations right now are so rapid. It's near impossible to integrate them in a meaningful way. We're just reacting.

Mike: I think humanity is a sturdy beast. I think we'll be all right. But it could take time, and some of it won't be pretty.

Lawrence: The word 'sturdy' speaks to something else I wanted to ask you. Hopper experienced these cycles, which most humans do, and indeed most artists do, of massive success and deep failure, both commercially and artistically. Did you draw lessons of artistic resilience from his story, or had you learned those lessons already?

Mike: I suppose I've learned some of those lessons already, but Dennis is an excellent example. He burned out for about 10 years after his failure with The Last Movie, but he still came back. It's so wonderful. He came back, and he got himself straight. Though I think he was a pot smoker till the end of his days. But he swore off drink and hard drugs, and he turned himself into a reliable elder of Hollywood. It's an incredible transformation. He came back from the brink, and I find that very inspiring, very lovable as well. I see pictures of him in his later days, with a twinkle in his eye. So wonderful.

Lawrence: Did you learn much about what the spiritual component of his life was?

Mike: No, and I'm not sure there was a whole lot of spiritual component, as you put it. He wasn't a big reader, for example.

Lawrence: That surprises me.

Mike: He was not a big reader. He would talk about film and art, but was never a big reader. And as far as I know, never involved in any particular spiritual discipline or religion, or system. There's no Buddhism in there, no spiritual practice that I can find—his art was a spiritual practice, I think.

Lawrence: There was a quote of yours about the album capturing the whole strange adventure of being a human soul on planet Earth. What were you most interested in illuminating? What excites you artistically when you think about sort of the human condition?

Mike: I never think about it like that, as far as what excites me most. While making the Hopper record, I just noticed that I got to say a lot in the songs about what it's like to be alive, like at the end of “Golf, They Say”: "Man or woman looks back cold, and weighs the work that's done.”

I think storytelling has that power to touch into the larger story of humanity, and I think, toward the end of working on this Hopper record, I realized that I'd done a bit of that, and that's really what that quote refers to.

At the start of the record, even though we know now that he could never really lose the Kansas that was inside of him when he was a kid, he just wanted to get away from Kansas and leave it. And that's a normal human condition to be able to escape and transcend your background and where you came from, and invent yourself.

Lawrence: It was so powerful in the short film when you went to his grave. I had no idea, I mean, that was so unexpected. Such a humble final resting place, yet so beautiful.

Mike: Yes, indeed. A Mexican graveyard.

Lawrence: How did that come to pass, do you know?

Mike: I don't know. I haven't read him specifically stating why he wants to be buried in Taos, but I guess that’s where he felt most at home. He thought it should be his resting place, and it's clearly his decision.

Visit Mike Scott and The Waterboys at mikescottwaterboys.com and follow The Waterboys on Patreon, Bluesky, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. Purchase The Waterboys' Life, Death and Dennis Hopper from Sun Records or Qobuz, and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments