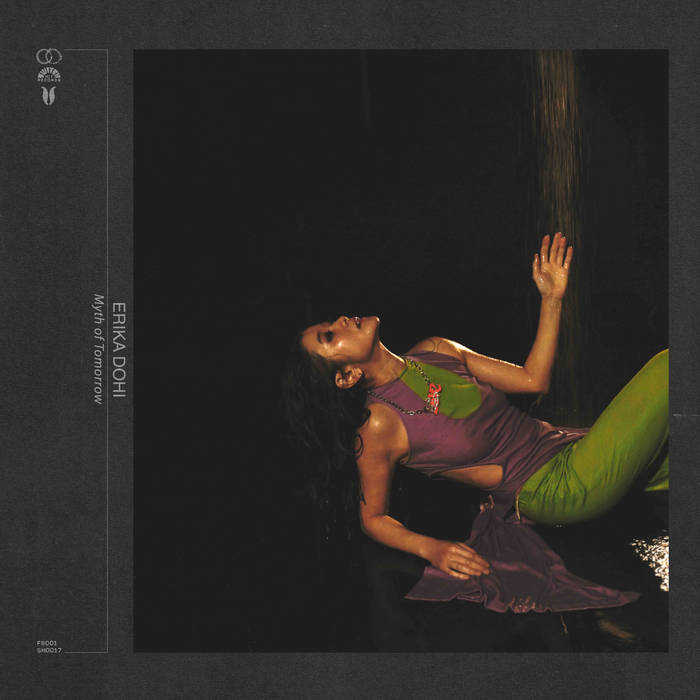

On the cover of songwriter, composer, and pianist Erika Dohi's sophomore album, Myth of Tomorrow, there is an image of her running, arms mid-swing, legs mid-stride. Her face is somewhat out of focus, and her expression is strained; her deconstructed outfit is a flash of purple and green against the black night, with only a few moonlit ripples suggesting that she is rushing past some waterside location. It's a dramatic portrait, all in the secondary colors of Halloween, made even more dramatic by its orientation: sideways, as if she's headed straight into that dark night sky. It's the titular theme of the album manifested visually: tomorrow is a myth, and yet we, like the Dohi we see, strain and toil and care so much.

It feels important to discuss the visual component of this work, given Dohi's cinematic scale and vision. Spoken word, in English, Japanese, and Spanish, is often a component (singing is a new addition, but the words are no less crucial in either context). Grand celestial references are woven in, and field recordings add life to her pieces while collaborations broaden them beyond what Dohi alone can accomplish. The textures present can shift from acoustic elements or antique electronics (see the Ondioline that she used to create many sounds on Myth of Tomorrow) to fully digital explorations within the span of a song. It all communicates how much she cares about the work she creates and her compassion for other beings she meets as she continues pushing forward to the next tomorrow.

Dohi is based in New York City now, a fact that finds its way into her compositions, and we spoke through virtual channels about how her music manages to combine spiritual meditations, musings on place, and elements of play into one cohesive message.

Meredith Coons: One of the things that I found interesting, right off the bat, was that you used the Fairlight CMI a lot on this recording. It was just recently the 40th anniversary of Kate Bush's Hounds of Love.

Erika Dohi: Oh, no way.

Meredith: Yeah. And she was famously a huge devotee of the Fairlight.

Erika: That's really good to know. When we were using the Fairlight, we were told that that's the most important instrument for that record.

Meredith: So what inspired you to use it? What qualities does the Fairlight CMI possess that made you want to incorporate it into Myth of Tomorrow?

Erika: The reason why we brought it in is that my record is funded and deeply tied to the Forgotten Futures residency with Figure 8 Recording. Forgotten Futures is a foundation that Gotye, the pop artist, launched. He has these extremely rare instruments in his studio upstairs from the Figure 8 Recording Studio, where I had the residency. One of the instruments that he owns is the Fairlight. Honestly, I didn't really know about the instrument until my producer, William Brittelle, mentioned it. The look of it, too, is really iconic. It looks like an old computer. It's a massive instrument.

The result was kind of like bringing in another artist. It has its own personality; it's nothing like another synthesizer. I got an opportunity to use and experiment with a lot of other synthesizers, but Fairlight is its own unique thing. We had John Blackford, who is an expert on that instrument. Forgotten Futures brought him in, and he educated us on how to use it. That's the reason we were able to incorporate it. And then the funny thing is, the Fairlight kind of sounds different every time we hear it. We recorded it, and then we'd come back and listen, and it's like, "Okay, something happened to it. We played the same thing. I don't know." (Laughter) It's one of a kind.

Meredith: Tell me about some of the other stuff that they had there that you got to experiment with.

Erika: The first instrument that I got to experiment with from their instrument collection was the Ondioline. It's a French instrument from the 1940s.

Meredith: Wow.

Erika: Yeah. One of the first synthesizers that was invented. It's a monophonic instrument. You can create different timbres using these levers, but on the back, it's a tube. It was made by Georges Jenny. This is really the biggest thing this foundation does: preserving the instrument and its legacy, because not many people know about it. Everyone knows the theremin, but this one is not really known. Sometimes it can sound like a flute, it can sound like a violin. It's really beautiful.

Meredith: So then what were some of your old favorites that you were excited to bring back to this collection of songs?

Erika: Well, I bought myself a Prophet 6 in 2021, or something like that. On my first record, I got to experiment with that. I kind of had to have it. It was expensive, but I really fell in love with the Prophet, so I bought it. It's one of the main sounds that are on "Ame Onna," "Aratani," and "Myth of Tomorrow." I wanted to write on the Prophet, just to have sounds I can replicate and toy with. You know, Radiohead's “Everything In Its Right Place”, I think? It has a super iconic opening with the synthesizer. Everyone knows it right away. It's that kind of thing, where I wanted the sound to be unique to myself. I actually wrote those three songs mostly on Prophet, and then we added layers of synthesizers, including the Fairlight, on top, basically orchestrating the piece using the Fairlight. And then the other guest artists were wonderful.

Meredith: What drew you to those collaborations?

Erika: I really picked my favorite musicians that I like to play with, ones that I have improvised with before. Kaoru Watanabe is a taiko player and a Japanese flute player. I've been a fan of his for a long time, but this was a new collaboration. And then Miyama McQueen-Tokita, she's a koto player who's also on the record. This was also a new collaboration. Including Japanese instruments was a new idea. But Adam O'Farrill, who plays the trumpet, I met in Banff in 2013 when we were students there. I've always loved his playing. And Lauren Cauley is a dear friend of mine. She's a violinist, and we have collaborated a bunch at this point. It was natural for me to want to have her on board.

A lot of the process of making these records is just being in the studio and creating together. I don't take all the credit for the compositions because they were a big part of it, too, especially with "Saturn Square Venus," which is the violin and piano track. I did the piano part, and then I sent it to Lauren, and she wrote the violin melody. That was complete collaboration.

Meredith: So she was responding to what you had recorded on the piano and adding the violin on top of it. Did you have the concept for the title of that track going in, and you sort of knew the relationship that you wanted those instruments to have to each other, based on that suggestion: "Saturn Square Venus"?

Erika: Yeah. Are you familiar with astrology?

Meredith: Yes. (Laughter)

Erika: As you can see, I'm very into that. And, yeah, I wrote the piece when that transit was happening. Saturn is a planet of restriction, orders, discipline, and Venus is beauty, art, and music.

Meredith: Connection.

Erika: Yeah, all the good things. (Laughter) When Saturn squares Venus, there's restriction to that, but then within that, there's so much beauty. I wrote it when I was struggling a little bit, love-life-wise. Venus is, of course, related to love and lovers and all that stuff. So it's that feeling of not being able to let go completely. Or there's some restriction there.

Meredith: Like, boundaries?

Erika: Yeah, boundaries.

Meredith: The piano on "Saturn Square Venus" immediately registers as romantic. That's the Venus element, right? And then the strings come in, and they are the boundaried element?

Erika: Well, I mean, we didn't really talk about it like that. I didn't tell Lauren to be Saturn. (Laughter) It just kind of came out that way. But also, the piano part being romantic—beautiful, but also ephemeral—there is a sadness or something under that, a struggle as well, within the piano part.

Meredith: That's true. They're both sort of serving both functions.

Erika: Yeah, exactly.

Meredith: Now I see. I love the concept of that and the execution of it. It's fascinating to me how suggestive your titles are. They serve as these guideposts for what the song could help you to imagine. I would love to hear a little bit more about that part of your process.

Erika: Sure. I would say the titles might not directly sound like it, but all of my compositions and lyrics are deeply derived from my yoga and meditation practices. Astrology, meditation, yoga: those are all kind of the core of my being these days. I mean, "Ame Onna," that's "the rain women." That's the direct translation of the title in Japanese.

Onna means girls, and ame is rain. It means women who bring rain everywhere we go. It's folklore from Japan. Traditionally, it was a yokai, which is like a monster, that creates rain and snatches babies out of their mothers. But then, in modern days, Ame Onna is said to be a person who brings rain everywhere. I was that person. I mean, I still am sometimes. (Laughter) On any outings and/or important events, it would be raining. I used to get so upset about that, but now, it's like, "Okay, well, that's just how it is." But in the lyrics, I talk about how the preserved flower doesn't wilt, yet it accumulates dust. That really talks more about the ephemeral quality of the living thing. Why would we change something impermanent? And it's also about permission to cry when you want to cry. It's tied to that a little bit, using the term "rain women."

Then "Aratani" is a song I wrote when I was back in Japan. My grandfather was alive when I got there, but he was really sick. I mean, he wasn't really even sick at that point; he was just dying. We knew it was happening. And I happened to go to Japan at that time. I didn't know he was so close to death. But I made it to his final days, and I was able to see him.

For me, the feeling of going to Japan is very nostalgic, and also kind of tender. I left home, my hometown in Japan, when I was 15. I get to go home maybe once a year or something, but that time is so limited, so every memory that I have is vivid. If you see something every day, then you kind of don't see the changes, right? But if you don't see it every day, you really see, "Oh, this person is so much older now; this building is so much older." You see all the changes so vividly. It just appears.

I wrote the lyrics when I was back in my hometown, Osaka, when my mom and my grandma were rushing to the hospital, and I was on standby, waiting to hear back. I was sitting on my grandfather's chair, contemplating all of the memories, basically.

Meredith: Thinking about impermanence, what you're able to preserve as memory and what isn't guaranteed, that's such a theme of this album. And it's called Myth of Tomorrow, because tomorrow is not guaranteed. What you're saying definitely makes sense and feels very much a part of what you're communicating with this work.

Erika: Thank you. "Myth of Tomorrow" is the title track. The lyrics are like, "I care so much," because I struggled in 2020 when I started this album. It was a big moment for everyone, but it was a really transformational time for me, because I was going through a divorce. And then divorce meant separation. I was in Texas with my ex. I wanted to go back to New York, because Texas wasn't for me. So I went back to New York to freelance as a pianist, and then COVID happened, and the scene was gone. It was really tough, I was like, "Alright, now I'm alone, and I don't have money, I've got no job."

Everything just went upside down for me. But then that meant to really go within, and that's when I dived in, heavy, on meditation. My teacher at the time, Jared McCain, had a yoga school in Brooklyn. He had to close it because of COVID, but he shifted yoga and meditation online, so I was able to do meditation with him regularly. I clung onto that because I was just so lost. My biggest fear was being alone. That idea was so horrifying for me, but that's when I started meditating every day.

Meditation is really facing your biggest fear, because you're not distracted by outside things. You have to sit with your uncomfortable feelings. You don't have to feel when you're busy doing things. But if you are alone, sitting with your thoughts, you have to face them. And then I realized that I just keep running from problems. I mean, that's the reason why I moved back to New York, because I couldn't sit still or something. And then I blamed my unhappiness on other people, like my ex-husband; it was not his fault. I just couldn't find my peace within.

"Myth of Tomorrow" talks about that, like, "If you end up with this person, you'll be happy; if you gain this thing, you're going to be happy. That's a mistake."

Another thing that saved me during the pandemic was small interactions with my neighbors, people that I just say “hi” to on the street, or the owner of the pet shop, or the bus driver. The smallest interactions saved me. Just to even get a little smile from somebody, you can't take that for granted.

Meredith: Yeah. I feel like there's almost a stigma that some people have around "pandemic albums," and culturally, it almost feels like we're being forced to move past that time, like we're supposed to just kind of get on with it, get over it, and it really feels like you're challenging that. Especially in the final track, which seems pretty direct in its references to the pandemic. "1111 / First Responders April 29, 2020"? Am I correct in clocking that final field recording as the pots and pans from the balconies?

Erika: Yeah, exactly. That recording represented everything about the album, really. I recorded that on that day in April. I was improvising on the piano, so the piano parts that you hear are me. And I was so sad when I was playing, like, "Oh, my God, I don't know what's going to happen." There was no rush to go anywhere. I was so lonely. My way to express myself was all I had. I didn't even have friends uptown at that time, where I live. Then, "Okay, well, I guess I'll do some improvisation." And then my neighbors just started hitting the pots and pans, and they were so loud! (Laughter) I know they were doing it for the first responders, but I got so much courage from that. It felt like cheerleading for me. It felt like, "Oh my gosh. I'm not alone." It turned out that I was recording what I was playing, and then it turned out that I was able to record them as well, which was nice.

Meredith: That's amazing. And it really does end the album on such a note of hope. Maybe it's just because I was able to figure out that context, what that sound was, but you can also hear the people cheering in it, and you can hear that it's kind of celebratory, you can hear the space in it, that it's this outdoor, collective moment.

Erika: They must have been pretty loud, because I was in the living room, and the windows are not right next to it. Also, it was April, so it wasn't the beginning of the pandemic. At that point, it had become their ritual. It was just so solid. It went on for a few minutes. They really just went for it every day. Sometimes my neighbor would bring out a speaker and then start playing Frank Sinatra's "New York, New York." (Laughter) It was fun. It was kind of like a party.

Meredith: That's very cool. I appreciated you being more direct in that reference, because it feels like people try to dodge it, and they shouldn't.

Erika: Yeah, it's pretty direct, for sure. I mean, it says it all.

Meredith: It's like meditation and sitting with it. It all ties into that practice.

Erika: Exactly.

Meredith: Is there anything that you haven't shared that you really want to share?

Erika: Well, I just want to mention one track with Shahzad. Shahzad Ismaily is an amazing musician and also the studio owner of Figure 8, and I had an opportunity to improvise with him. So that's the track that we have, "Shahzad + Erika." It was such an inspiration to play with him. Sometimes you get to have those moments with incredible improvisers, and I feel like the track kind of captured that.

I'm so grateful to him for having me for the residency. That studio is part of this record. I had 21 days of residency with Forgotten Futures in partnership with Figure 8 Recording. That's how the record was made, with the residency. So, just being in the studio with my producer, William Brittelle, and Michael Hammond, an excellent engineer, and having that time there, I was able to really experiment. Before the residency, I wasn't singing. I got to do something completely different because of the time, space, and openness they provided.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMeredith Hobbs Coons

The TonearmMeredith Hobbs Coons

Comments