In the obsessive world of record collecting, comedy record enthusiasts tend to be regarded as the low men on the vinyl totem pole, that is, if you chart such things. Walk into almost any record store and ask for the Comedy section, and you're bound to find yourself whisked away to a dark and dank corner littered with ring-worn Moms Mabley and Bob Newhart LPs, yearning to breathe free. That's if you're lucky and don't get shown the door in response to your query.

That may sound a bit harsh, and I'm taking some liberties here. As someone who collects a multitude of genres of music and does have a longtime fascination with comedy records—the more obscure the better—I know that the majority of the population couldn't care less about comedy vinyl. Outside of a few big names, the kids of today aren't exactly circling the shops for copies of the umpteenth Woody Woodbury album or appreciating the bizarro brilliance of Murray Roman.

When I started collecting comedy records several decades ago, I didn't have a specific yen to amass them. Rather, like so many records, I appreciated the fact that they existed and would pick up anything that looked interesting and unusual, the more obscure and curious the better. This is a trait I still follow when record shopping in all genres. Yes, I love plenty of mainstream music, but I've long been attracted to the fringes of obscurity, be it a private-press psychedelic opus or a lounge singer direct from a Holiday Inn in Podunk, USA. Whatever catches my eye and ear, I'm attracted to.

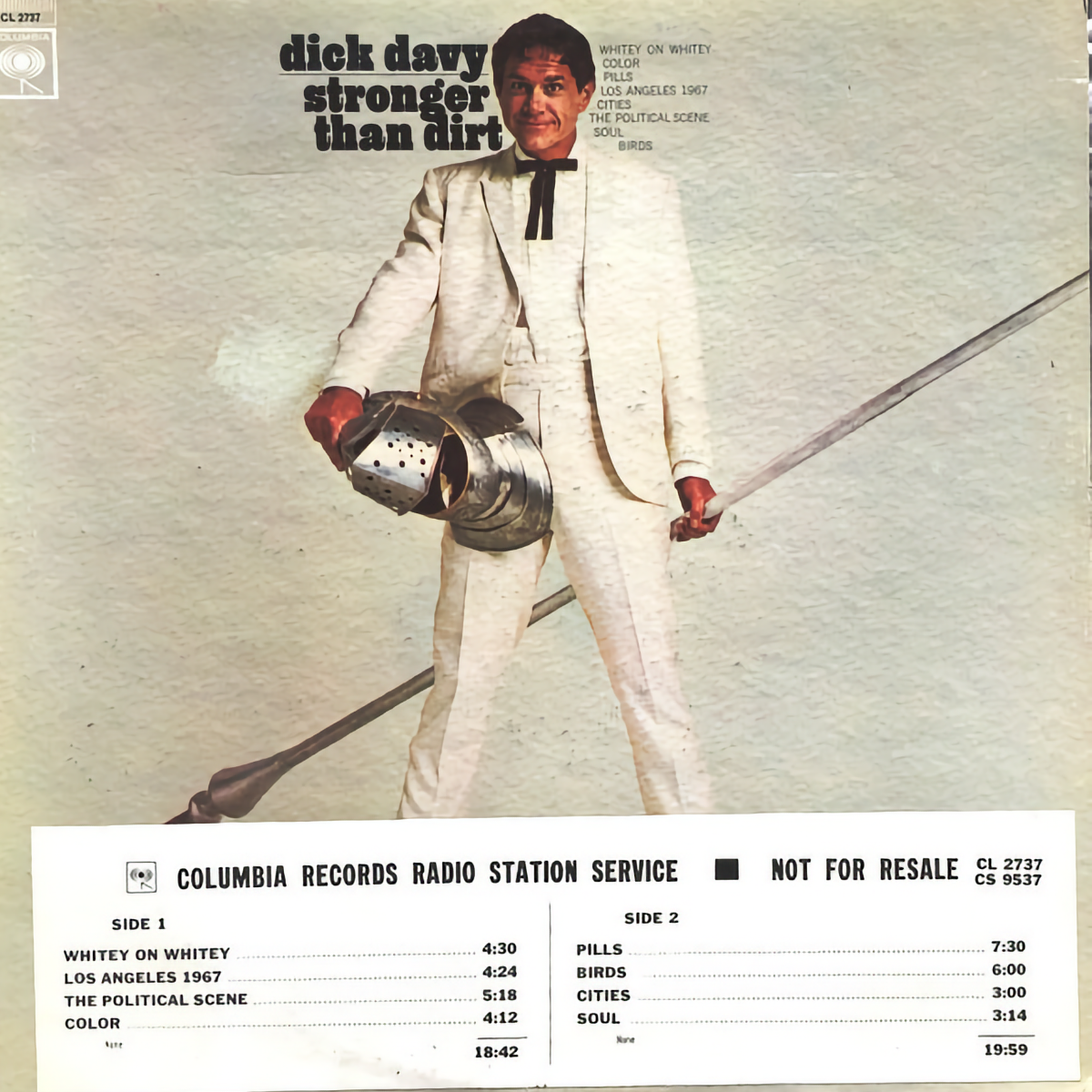

That explains how I first came across comedian/personality Dick Davy's debut comedy album, You're a Long Way from Home, Whitey. Released by Columbia Records in 1966, it features Davy on the cover looking like a confused bar mitzvah boy who got left behind at a civil rights march on the way to shul.

Things get stranger still when you read the cover and note that the album was recorded at the Apollo. They can't be referring to that Apollo Theatre, the iconic home of rhythm and blues, soul, and jazz—a place that birthed countless generations of Black talent?

Sure enough, it's one and the same. Back in the fall of 1965, comedian Davy found himself sharing a bill at the venerable theatre with crooner Brook Benton, pop group the Orlons, and the dynamic Ike and Tina Turner Revue. With no eyewitness accounts of how he went down with the presumably largely Black audience, we're left to muse over a Variety review of the affair, at which the reviewer seems rather bemused by Davy's comedy schtick.

And what a strange schtick it was. Portraying himself as the "Arkansas Fellow Traveler," Dick Davy appeared to audiences as a new transplant to the big city of Manhattan, a wide-eyed white boy who sounded like a Black man who wandered into the civil rights movement, poking fun at racists and the Ku Klux Klan while musing on the current state of social justice and politics in an aw-shucks manner. Even in the sizable world of stand-up comedy that was booming in the sixties, Davy was charting a path uniquely his own.

A lot of the intrigue that surrounded Dick Davy—and those fascinated with him—is due to so little being known about him until recently (and even then, there are plenty of blanks to fill in). Thanks to Davy archivist and producer Jason Klamm, the public knows a bit more about the life of the comedian. Born Richard Davy, he grew up the son of a rabbi in Utica, New York. Later, the family moved to NYC, a world away from his supposed origins in Arkansas.

As a young man, he became interested in folk music and the civil rights movement, touring folk clubs as a singer and comedian, as well as joining Students for a Democratic Society and the Freedom Riders. But in the large folk circle of travelers, it must have seemed clear to Davy that he needed a gimmick, something that was unique and expressively his.

It's not clear when or how the cityfied Richard Davy became Arkansas-bred Dick Davy, but we can now get a glimpse of his early transmigration thanks to Presenting . . . Dick Davy, a new vinyl LP from the Stand Up! label. The bulk of the material on the album comes from a pair of acetate discs found amidst Davy memorabilia that had previously belonged to his brother Daniel Hoffman, which were in the possession of Davy's niece, Sharon. After album producer and comedy archivist Klamm connected with the niece, she graciously allowed fellow archivist (and overseer of the Firesign Theatre archives) Taylor Jessen to digitally transfer them.

The recordings, made in 1962 at the Bitter End, show Davy working on his persona. One recent reviewer called it "Smothers Brothers–type with a Jewish and Southern mix," which is as good a description as any. Davy comes across as a balladeer mixing humor into the fray. A highlight for me is "The Bar Mitzvah Dude Ranch," a sly Southern-styled telling of a dude ranch for Jews. With the breakout success of writer and comedian Allan Sherman and his Jewish-themed parodies of pop and folk songs, suddenly ethnic humor had crossed over to the mainstream. Sherman's label, Warner Brothers, was shocked to find his albums selling like challah bread in middle and southern America. Suddenly, the idea of Dick Davy doing a pseudo-Texan Jew dude ranch bit doesn't seem so out of place.

But rather than sticking to strictly Jewish humor, Davy decided to climb headfirst into the civil rights movement, positioning himself as a Will Rogers–esque bumpkin for the changin' times. By giving himself into this persona, Davy seemingly transformed into his aw-shucks character, a confused yokel in New York City. It's not clear how long Davy was working the clubs before he signed a deal with Columbia, but needless to say, it was a big step up.

Dick Davy's two Columbia albums, produced by John Hammond.

Regarded as the pinnacle of the establishment record industry, Columbia Records had made its name largely as the home of classical and pop artists. Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and Rosemary Clooney were some of their biggest sellers in the fifties, along with Broadway cast recordings. Head A&R man Mitch Miller made his disdain barely hidden for rock 'n' roll, considering it nothing more than a passing fad that needed to be stomped out. On the opposite end, producer and talent scout John Hammond was deeply involved in rhythm and blues, jazz, and folk music. As history has shown, seemingly every great name Hammond signed up and produced became a legend, though not always at the time (Bob Dylan was referred to as "Hammond's folly" in the hallowed halls of CBS after his debut album flopped).

It's surprising, then, that the venerable Hammond produced both of Dick Davy's Columbia albums, released in 1966 and 1967, respectively. I'm not aware of John Hammond producing any other comedy acts in his long career. To be fair, though, Columbia wasn't exactly known as a comedy bastion to begin with. Before Warner Bros. hit the comedy jackpot in the early sixties, comedy and humor records were the stuff of independent labels; the majors couldn't be bothered with them. Even with the comedy record boom, CBS seemed to lag behind. Worse yet, they had absolutely no idea how to promote what funny talents they had. Luckily for Davy, he had a good manager, and TV talk show host Merv Griffin took a shine to him, having him as a guest on numerous editions of his show and even penning the liner notes for his first album.

One of the reasons that Dick Davy isn't better known is because of how short his professional career was. After Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination in 1968, Davy retired his racial comedy, focusing on more hippie humor. An appearance on the Bitter End show featured on Presenting and, together with his earlier pre-Columbia recordings, manages to allow for a bookending of his comedy career.

By the dawn of the seventies, Davy had seemingly retired from comedy, working full-time as a teacher in Manhattan. Outside of a solitary 1975 interview for writer Phil Berger's stand-up comedy anthology The Last Laugh, he kept a low profile. Even his romantic partner for the latter part of his life knew nothing about his previous career until Davy died in 2007. Eventually, she unearthed scrapbooks of his from his prior life and began to learn about his stand-up years.

Through hosting his Comedy on Vinyl podcast, Jason Klamm began delving into the life and times of Dick Davy, learning about him after tracking down Davy's older brother. All the years of research and work have led to the unearthing of these fragile acetate discs, which listeners can now enjoy on the new vinyl offering from Stand Up! Records.

For younger generations that have grown up in the decades after the civil rights movement, it may seem strange or uncomfortable listening to Dick Davy's comedy—and it seems to me that Davy enjoyed that element of discomfort and used it against audiences in a savvy way. Listening to his Apollo recordings, you can hear that he'd clearly won over the audience. And maybe sixty years later, he can still get a new audience.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments