The interview I did with Jens Kuross took place about an hour before he had to leave for the airport in Boise, Idaho, to fly to London and work with a band he's worked with before. He's a multi-instrumentalist who has a degree in performance, another in jazz drumming, and, of course, he sings beautifully and produces as well.

Something that stood out to me was how fast Jens talked. He's also an energetic person with a strong sense of humor, and I remember thinking in the moment of how Crooked Songs swiped right on my emotions of loneliness, iridescent melancholy, and this unavoidable desire to self-reflect on countless things. Yet there's a sense of hope in the album as well, and I think that the contrast of Jens over Zoom and Jens on Crooked Songs might represent how well he's able to sit with the music he creates, and how he lets it be right where it needs to be.

In his solo work before his latest album, Crooked Songs, you can hear the multitude of layers of production in songs like "Spiraling" and "We Will Run." Bells, drums, many vocal tracks, samplers, and generally at least an amount of production that shaped and commanded the aura of the songs well beyond the rawness of a live sound. Crooked Songs is antithetical to the way Kuross made much of his music before. The album is naked and sparse, only containing Kuross's sullen voice and an electric piano that leans on warm organ-like sounds.

Jens grew up mostly in Ketchum, Idaho, had started piano lessons when he was four, and started drumming when he was around ten. He spent a good amount of time living in Los Angeles as a session musician and songwriter, though he left after souring on the L.A. music scene. Believing that he'd never find an audience there, he returned to Idaho.

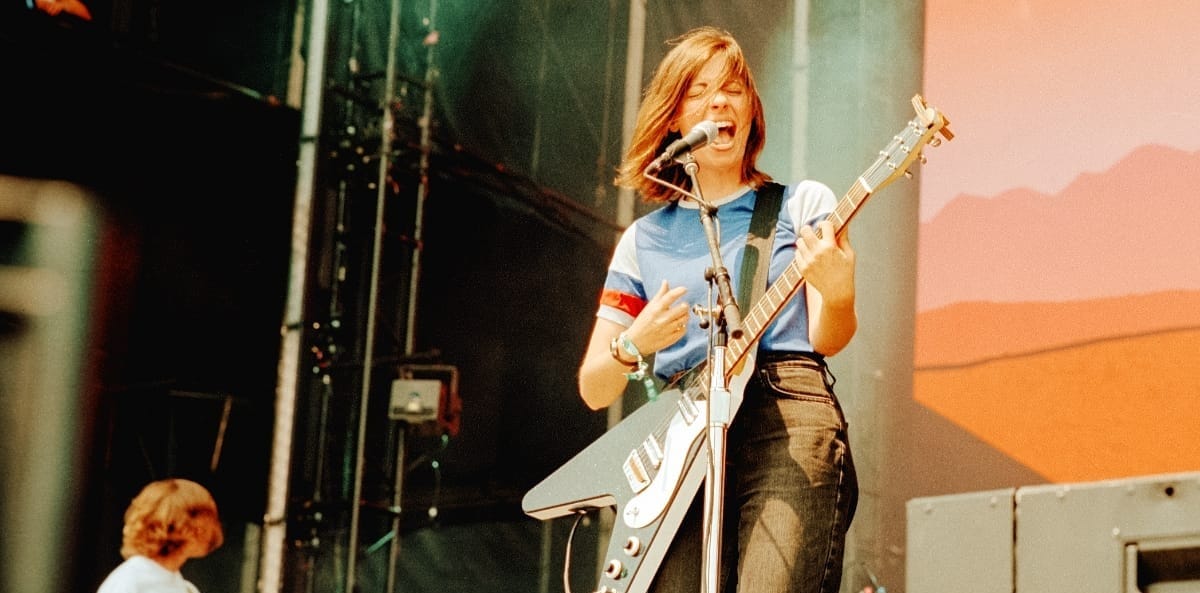

In December 2023, musician and producer Hayden Pedigo met and saw Jens play in the basement of a Shriners lodge in Boise, Idaho. Pedigo said of the performance, "Jens played these beautiful, touching songs that sounded like something like Arthur Russell meets Harry Nilsson. By the second song, I was in tears. It was the first live performance that ever made me cry. At the end of his set, I told my wife that it was the single best live performance I had ever seen." Reading what Pedigo said, I wanted to be in that room for that performance, to be engulfed in that music at that moment.

Pedigo reached out to Jens a few days after the performance, listened to his previous albums, which didn't sound like what he heard that night, and proposed recording an album just like that. Jens agreed. It's easy to feel that rawness, the heaviness of reflection and retrospection in Crooked Songs.

Jonah Evans: Hi, Jens, thanks for being here today. What are you getting up to? What's on the docket?

Jens: I'm actually about to fly to London. There's a band out there that I've done a bunch of work with in the past, touring, and I'm working on their next record with them. So they're flying me out there to write and record with them, which is very nice.

Jonah: So you're going there to produce?

Jens: No, I'm just playing keys and contributing ideas. But I think there'll actually be a producer there.

Jonah: Okay, that's fun.

Jens: I don't know if it's obvious or if you noticed in my bio, but my day job is being a musician, and my artist career is also being a musician. So I do a lot of music work that's just blue-collar music work, playing on people's records and, you know, sort of keeping a roof over my head.

Jonah: That's cool that you're able to play music in various ways. And I saw that you'd spent a little bit of time as a session drummer as well.

Jens: Yeah, yeah.

Jonah: So you grew up in Boise, Idaho, yeah? Just Boise or in different places as well?

Jens: I grew up in a town called Ketchum, Idaho, which is about two and a half hours from Boise up in the mountains. I live in Boise now.

Jonah: What was your relationship to music growing up, and when did you realize your connection to music?

Jens: You know, my dad was always a big music fan. So he was always listening to records, and he was kind of an amateur pianist, guitarist, singer—in the best sense of the word. He really loved it, so there was always music in the house. I started piano lessons when I was four, and I don't know how well I remember what was going through my head when I was four, but I do remember just loving sitting at the piano and making stuff up. You know, they have videos of me improvising songs on the piano. They're just complete gibberish, but it brought me a lot of joy. And then we moved to Idaho and had to leave the piano behind, so I stopped piano lessons and focused on drums, starting around the age of ten, which I really connected with as an instrument.

It's difficult to say when I knew I had a connection to music, because when you're a ten-year-old, it's just fun. So maybe something clicked around that age, but it was happening on a level that I wasn't aware of. My whole musical trajectory, starting from when I was four to now, has been a relationship with music that's gradually increasing in intimacy, depth, affection, and profundity, just very slowly. It's not like a lightning bolt moment here or there, you know. It's just a gradual increase in depth and magic.

Jonah: I like how you outline that it's gradual. It's almost kind of like a natural experience of something and wanting to be a part of it, and you just keep doing it, learning and growing as a person—kind of a convergence.

Jens: Yeah, it is. I'm not the kind of person who thinks that there is necessarily fate or destiny, those kinds of things. In the same way, I don't really believe in soul mates, but I do think that some people are more predisposed to certain careers than others. Music was something I was predisposed to do, even though, at the time, I just wanted to be a rock drummer. I knew music was important, but that grew and changed. And then I fell in love with jazz. I wanted to be a jazz drummer, and I studied jazz really intensely in college and grad school, and then work kind of took me out. You know, it's obviously damn near impossible to make a living as a jazz drummer. There are probably about a dozen people in the world who can really do it.

Jonah: I didn't realize that. That's incredible, because jazz drummers are the craziest drummers.

Jens: (laughs) In a number of ways, yeah. But, you know, music was kind of always the North Star, or I don't know, music, beauty, art, something like that, something that's difficult to define, is the star, and it kept me on the track of music. But I was always rock drumming, jazz drumming, composing for singer-songwriters. I've done a lot of work in Berlin, like with deep house producers and stuff like that, which is random, because it doesn't seem like the record you're asking me about, Crooked Songs. I'm sure it sounds nothing like that music at all. They don't seem particularly well related, but I've just been all over the map with music.

Jonah: Hayden Pedigo first saw you in Idaho in 2023 when you just played with just your voice, Wurlitzer, and ambient sounds. He said that your older songs are more polished and missed the weight and sincerity he'd heard in that live performance. And in Crooked Songs, there are these audible moments, mostly at the beginning and end of songs, where I can hear you taking a breath using only an electric piano and your voice. What kind of discussions did you and Hayden have, or did you have with yourself, about this record and this minimalist approach, allowing the songs to breathe this way? (No pun intended.)

Jens: Well, Hayden was moved by my live performance, like really moved by it, like I've never experienced anyone connect with my music like that before. I didn't think it was possible. He was so insistent that the proper way to present my music was like that, because he had such an incredible response to it, and it affected him so deeply. He talked me into recording songs like that. And so I just went back to my living room, and I'm like, "Okay, well, how do I best recreate that?" Because when you're recording and when you see someone live, there are all kinds of stuff you hear that isn't the actual music, and it's difficult to say how much of that is important, and how much that's contributing to Hayden's response.

And so I decided, "Well, I'm just going to record the sound of a room. I'm just going to put up room mics and play the songs in a room because that's what Hayden heard, and I'll see what that sounds like." I mic’d it so you could hear the whole room, and not just the vocals and the piano, and it seemed like the right thing to do. When I listened to that one song, I thought it was really good. I liked the way it sounded. I liked the fact that you could hear my chair squeak and you could hear my breath, like you said, and all the keys clicking. It just made it so much more personal. And I'm like, "I think this is it." And I sent it to Hayden. He's like, "Yeah, that's definitely it, that's definitely it."

I was kind of skeptical that it would be possible. You go to shows, and sometimes there are just magical shows, and you shouldn't try to recreate them. You should just take it as there was a moment in time, it was beautiful, and we connected to this, and it was cool. You just let that go. I thought, "Well, that was a good show, but I’m not sure I can recreate it." I came close, though. I haven't listened to Crooked Songs in quite some time, but the last time I did, I remember thinking it was very special. It made me nervous because it was so raw and unpolished, so warts and all. I thought, "People are really going to like this, or they're just going to ignore it." It felt like a risk.

I'm still kind of nervous about it, because I have a whole other record that I made before Crooked Songs, that I made once I moved back to Idaho, in this living room, and it sounds great. The songwriting is great, and the production is much more nuanced. On it, I'm interfacing synths, pianos, drum machines, and acoustic drums, and I’m really proud of it. But something about it seems kind of dull to me now. I listened to it, and it doesn't seem particularly magical in the same way it used to. And I think part of that is just because it's old now and I've moved on.

I listen to most music now, and it feels pretty un-magical, certainly most new music. It seems too narcissistic. It seems too like, "I'm trying." An artist is making an album, and that artist just wants people to think they're cool, and that's why they're making an album, and something about that I find incredibly off-putting. I don't know. So that record is probably never going to be released. (laughs)

Jonah: It's interesting you said that because I watched one of your interviews when you had a residency at Idaho State University. It was a mini-documentary thing. You were teaching there. You said, "I am very much a proponent of the idea that limitations are kind of a prerequisite of creativity. You need those challenges to work around, because creativity in one sense is problem solving, so if you have infinite choices, you don't really have a problem, and if you don't have a problem, you don't have to be creative." And it feels like this record is a challenge, but it also seems like you’re reaching some of those theories and marrying those ideas. Crooked Songs is so minimalistic, but there are still layers.

Jens: Yeah, very true. Because of the nature of recording technology, I can have any instrument, in any room with any reverb, any combination of random effects, and on any microphone. It's like it's too limitless. This record didn't take as long to make as the previous one, but there's still a lot of sitting there, as in I need the song to grow in such a way. And it's like, you have this part that isn't hitting hard enough, so we can add another drum thing here. This part needs to lift more, so we can add some pads in the chorus. You have all those tools available to you.

On Crooked Songs, all I did was play the piano and sing. And if it didn't hit hard or lift here, I just have to play it again until it does. So, that was very simple, but it was difficult. Most of those songs probably had ten to fifteen takes over multiple days before I found the one that I thought really hit home. Some of them might have come quicker, but I would imagine ten takes is pretty average. I live in a house that is not particularly well insulated, but fortunately, the neighborhood is relatively quiet. I have to do all my recording either early in the morning, before people start driving around, or late at night. So, I’d have a recording session in the morning, get as much done as I could, and then listen to it. If I didn’t get it, I’d have to hit it again late at night or the next morning. I think most of the takes ended up being early morning takes.

Jonah: What are some ways you think you attacked the layers in Crooked Songs using so few instruments? How do you think you reached the sound that you made?

Jens: Do you mean like the tone of the piano or the voice?

Jonah: I'm thinking, you only used an electric piano and voice to make a record. It feels like the record has those layers, or more layers, and you can feel the songs and oscillation of emotion and sonic resonance throughout the album.

Jens: I think the answer to that question, then, might be kind of unsatisfying. It just takes me a long time to write a song, a long time, mostly because of the lyrics. But then, once I’ve written it, I play it over and over and over and over and over and over and over again to really familiarize myself with it. Where does it lift? Where does it pull back? Where does it jump forward? What are the parts that really hit home? All this kind of stuff, and maybe those layers you're referring to are just a consequence of being so intimately familiar with the music.

Jonah: Intuition and repetition could be part of it?

Jens: Yeah. You learn a lot about a song after playing it a thousand times, which is really cool. I think most music is written kind of quickly. I was in L.A. briefly. I had a publishing deal, and they would send me to co-writing sessions. You’d get in a room with one or two other people, and they’d just try to write a song, writing, writing, writing. And I'm like, I can't. Everyone's trying to get two percent of a song that's going to end up on the next Rihanna record or something. It's a very dirty, uninspiring. Everyone's just throwing ideas at the wall. I think it's fine that some people work fast, but I like to sit with something and marinate in it for a couple of years before I record it. I want to write a verse and sing it over and over and over and over and over again, and then, maybe a year later, change two words. You sit with a piece of art for a minute, and you really marinate in it; some parts of it are revealed to you. You're like, "Oh, this part of the verse actually is antithetical to the rest of the song, and I need to change that." And that's not really obvious when you first write it, you know?

I'm not being prescriptive. This is just how I work. I take time. If you forgive the word, it's a very sacred process. And I don't want to rush it. Everything gets revealed to me in time, over long periods of time. And some of the songs on this record are five years old, six years old. Some of them are new. Some are maybe a year old.

Jonah: It feels like you actualize that spacing though, like with those breaths and in the last song of Crooked Songs, where you actually stop playing, you get up and you walk away, which can be heard, and you're actually letting the song sit in the moment of you performing the song. I thought that was cool how you did that.

Jens: I know "Crooked Song" has maybe a minute at the end of just the room sound. And I think every song had a good twenty to thirty seconds of silence after it. But the record label, and I'm not denigrating them, it's a very good label, and I'm very grateful to be signed, but they were like, "That's not going to work on streaming. You can't have a minute of silence after each song." There was a difficult conversation, so now there's maybe ten seconds of silence in between each song, or something like that. I tried really hard to keep it because I thought it was good. I thought you'd play a song, sit with it, and listen to the breath for a moment. If you were able to see someone play live, they'd play a song, and there would probably be some silence as they kind of shifted around and prepared for the next song. That's kind of what I wanted to get across in the album, too.

Jonah: I think it's there.

Jens: Thank you very much.

Jonah: You said you weren't going to release that other record, but how do you think you'll approach the next record after doing this one and stripping so much back?

Jens: That's a very good question. I've thought about it a little bit, but not tons. This whole record has been such a gift, such a whirlwind. I didn't think anyone was ever going to care about music again. I’m really surprised that this record has gotten some attention and people are asking me about it. I'm thrilled with it, so I'm trying to just sit with this record. I have thought about it a little bit, to your question, but I have no answers yet. I think it's a big question I have to ask myself, for sure, and I haven't quite. I'm not ready to really figure out what that answer is yet.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments