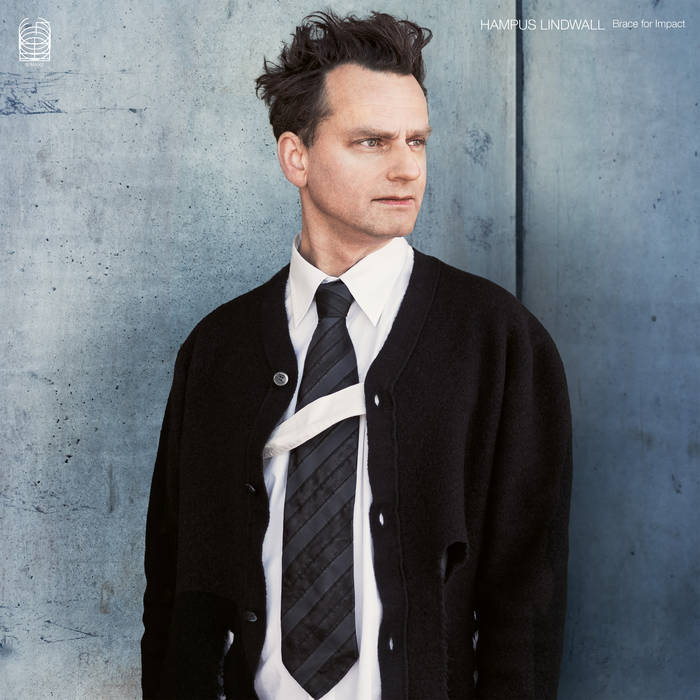

Hampus Lindwall has served as organiste titulaire at the Church of Saint-Esprit in Paris since 2005, occupying the same position the legendary Jeanne Demessieux once held. But his own music reaches well beyond liturgical duties. Lindwall’s new album, Brace for Impact, released through Stephen O'Malley's Ideologic Organ label, pairs centuries-old acoustic machinery with algorithmic processes, nineties rave and metal aesthetics, and the raw force of contemporary experimental music. Recorded on the seventy-eight-stop organ at St. Antonius Church in Düsseldorf, the album features O'Malley's electric guitar on the title track as Xenakis-inspired glissandos collide with metal riffage. Boomkat called it "post-internet organ music . . . informed by algorithmic processes."

Lindwall grew up in Stockholm during the nineties, absorbing the city's exploding club scene while learning guitar through copying Steve Vai solos from records. He soon discovered how the precision of metal virtuosity could meet the textural possibilities of electronic music. Lindwall’s horizon was further expanded through studying with Rolande Falcinelli, a mentor who moved easily between Greek literature, Italian cinema, and organ technique. He’s collaborated regularly with Cory Arcangel, Phill Niblock, Tarek Atoui, and Susana Santos Silva, and Londwall’s many recordings appear on Blank Forms, SUPERPANG, Matière-Mémoire, and Clean Feed.

Lindwall treats the organ as a living instrument rather than something set in stone. He uses iPad-based composition software and MIDI interfaces to generate music that is too complex for finger work. Every weekend, he improvises for hours during Mass at Saint-Esprit, turning the liturgy into an ongoing testing ground by subtly incorporating electronics, algorithmic patterns, and textures borrowed from experimental music. Through Lindwall’s efforts, an unusual feedback loop has formed between sacred tradition and sonic experimentation.

Lawrence Peryer recently hosted Hampus Lindwall for a conversation on the Spotlight On podcast. The two discussed the algorithmic and computational innovations that informed Brace for Impact, the surprising connections between metal guitar solos and baroque organ temperament, and why the organ (an instrument with roots stretching back to the third century BC) continues to speak to a generation of artists working at the edges of contemporary sound.

You can listen to the whole conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for flow, length, and clarity.

Lawrence Peryer: I'd love to start by talking about the new record, Brace for Impact. What is this idea of post-internet organ music?

Hampus Lindwall: I didn't come up with this. It was Robert Barry who wrote the text for the album. I was kind of skeptical to try to put some label on it, and I am not really sure what is considered the post-internet generation, because it’s the people who grew up with the internet already existing. So I'm a little bit too old for that. I think he thought it was influenced by so much internet media, internet art, and internet ways of working with algorithms and computers that it made sense. So I didn't protest, actually. I thought it was okay. I was also looking forward to seeing what kind of debate this could lead to later.

Lawrence: Has it stirred anything up?

Hampus: No, most people just repeat the phrase. You're the first one who really asked about it. (laughter)

Lawrence: I mean, to me, it's like a 'post-organ' album. It's almost a redefinition of what the organ can be and do.

Hampus: Yeah, that's what I wanted to do.

Lawrence: Tell me a little bit about Stephen O'Malley and that collaboration. The title track is such a powerful opening to the record, especially if someone approaches it thinking, "Oh, it's a record of organ music."

Hampus: I think it was a good piece to start with because, as you say, it's pretty definite that you're going to hear something pretty new. What's important to know is that I never consciously thought, "Oh, I have to renew any language.” It's not like research that I'm doing. It's just that this is the outcome of my whole work, my world, and my involvement with the art world and many artists that I work with, and all my own influences.

This piece is inspired by riffs coming from time to time that give impulses, and then "Metastaseis" by Xenakis, which has this incredible opening sequence where they do long glissandos on the violin. My initial idea, fifteen years ago, was to do this with violins, but that never happened.

I was invited to compose something for a festival, and together with a colleague who was doing the other pieces, we said, "Yeah, let's go back to our childhood passions," with techno on one side because it was the nineties, and also all this heavy metal. So I thought, "Why don't I try it with guitar?" When I wanted to record this, I asked Stephen O'Malley because he lives in Paris, too. He could record the guitar parts. It was kind of fun because he didn't know what it was going to be. I just asked him, "Can you play from F-sharp to D-sharp glissando, and it should take fourteen seconds? Then can you take from this note to this note, and it should take nine seconds?" I had the score, and it was very precise, so I could just patch everything together on the computer.

Lawrence: You've opened the door a little bit to my next question, which was going to be about the influences you moved through musically in your development, whether it was some of those heavy metal guitar players—Steve Vai, Yngwie Malmsteen, Eddie Van Halen—and then you mentioned Xenakis and others. From the outside, those are very different musical universes. From the inside, from your perspective, is there any connective tissue you've experienced through all that?

Hampus: Yeah. I grew up with a lot of music around me. My brothers were also playing instruments, so I always listened to many, many types of music. I was never interested in having a hierarchy where classical music is the best and pop and rock are less good or something. That was never an issue, the same with all types of culture that I consume. I have the same love for Visconti as for B-movies from the seventies. Is it good? It can be good in so many different ways. You have maybe different parameters to measure if a Bruce Lee movie is good than you have when you watch something else, or the same with music—you just have a different set of rules on how to analyze stuff. But quality is always the most important thing, and that’s what counts in the end.

Lawrence: Talk to me a little bit about the algorithmic process, where that comes from for you, how you translate a modality like that onto an acoustic instrument.

Hampus: That's a difficult question. (laughter) I think since the early 2000s, it has been a great tool for composers. At this research center in Paris, IRCAM, they started early to develop software for assisted composition. This influenced many of my friends who were working, studying, or teaching there. That actually influenced me, even though I was never a programmer, so I couldn’t really use this in the hardcore way they could. They code stuff, and then it comes out as notes. But there was more like a vibe that was interesting to me in the beginning. Then, as soon as I got an iPad with more ‘dumb’ applications that I could use—you know how it goes—I could start using this for my own work.

The most complicated is on "À Bruit Secret" where I use a tool called Gestrument, which is a composition-assisting tool where you can define a number of rules, like a scale or different chords, or different rhythms. Then, from what you have defined, you can paint or draw the music on the iPad. It was developed by a composer called Jesper Nordin, who is a Swedish composer. He built it for himself as a tool, and it has now become quite successful for others across all types of music, too. You can do pop songs or whatever with it.

Lawrence: Is there anything about the pipe organ from your perspective that makes it especially suitable for this sort of computational or algorithmic thinking? Or is it just that this happens to be your instrument and the approach you've chosen?

Hampus: I would say both. For me, it was natural to use all these tools, so I would have done it on any instrument. But a good thing is that over the past ten or fifteen years, there have been many pipe organs with MIDI. You can easily play them from the computer, which lets me compose things I couldn’t play with my own hands, so to speak.

Lawrence: I don't know why I never thought about the fact that there'd be a MIDI interface for a pipe organ.

Hampus: It's a perfect match. You can't have it on a flute, for instance, but for an organ, it's the best because it's already so mechanical. It's just like a huge machine.

Lawrence: There's something steampunk about that. (laughter) As I was listening to the Brace for Impact, every track I would say to myself, "Oh, this is my favorite one. I love this." It really builds and takes—there's definitely an arc. The track I come back to the most is "Swerve," though. That piece really stands out for me. But how did you approach the structure and the flow of the album? Were you telling a story?

Hampus: It's more pragmatic than this. Since it's also on vinyl, you have to count minutes on each side. So that leaves you with only a couple of different combinations. Then we thought, "Yeah, one strong one, then a bit mellow after”—how you sequence stuff normally. I don't even know if I did it or if Stephen O'Malley did it in the end.

Lawrence: I love this idea. It comes up a lot that the dominant medium at any given time ends up influencing the music and the composition. The example people use all the time is the limitations of the old seven-inch single and how pop songs took that two-to-three-minute convention. But it's also fascinating to me that you relinquished the sequencing. Not all artists do that, you know?

Hampus: But I think when you listen to it now and everything is going one after the other, it functions really well. I think it was a natural way of putting the tracks. I couldn't imagine them in another order now.

Lawrence: You mentioned earlier that Stephen recorded first, and you conducted him. I didn't realize his parts weren't entirely improvised. Was everything written? Were the organ parts written, or did you give him his piece?

Hampus: Yeah, I wrote everything first. It was just the easiest way to do this. He wanted to have timeframes and the pitch to bend, but he didn't know what type of music it was or anything. He didn't have a clue until I recorded the organ parts and put everything together.

Lawrence: Do you remember his reaction when he heard it?

Hampus: No, I didn't see him. I sent him the tracks.

Lawrence: What do you get from these collaborations? What insights do you come away with that you might not get by just working alone?

Hampus: I've learned so much from all these incredible people. I've collaborated with so many incredible musicians and artists. You learn a lot about the other person, but you learn a lot about yourself. It's when you come to another country—often you learn about the other country, but you actually learn more about your own country in contrast.

I've been collaborating a lot with composer and visual artist Cory Arcangel. That's been a great collaboration because when you work alone, you have so many questions, especially about your own work. I can work on it for a long, long time, and then I feel like I should just scrap everything. When we work together, we are always very easy-going with everything. We try to be more like Fluxus artists and follow what we think is good. I think that's been helping me a lot in putting together this album. Some of the pieces even come out of some of our collaboration concerts.

Lawrence: So you carry that sort of inspiration from those collaborations? They're not siloed into those?

Hampus: No, definitely not. Also playing with other instruments—Susana Santos Silva, who's an incredible trumpet player, I've been playing with a lot. As soon as I hear what she’s playing, I try to match something on the organ, and those things stay with me afterward. I incorporate a lot of things into the work. Otherwise, you know, also in the church where I play—not everybody knows this, but I play in this church in Saint-Esprit, which is very active. So I play at least four masses per weekend there, Saturday and Sunday, and I have around fifteen hundred people per weekend coming.

Then there are the more decorative parts where the organist is playing pieces that fit with that particular Sunday. Most organists, particularly in France, have this tradition of improvisation because you don't really know how long anything will take. There can be more or fewer people at the communion. You have an older priest who walks more slowly. Pieces are always tricky because they’re either too long or too short, so most organists improvise.

Lawrence: That's a fascinating bit of insight to understand what the organ player's experience has to be, the adaptability you have to have.

Hampus: So that's the thing. I have a small TV, so I can see what’s happening downstairs, and I need to know when the priest is sitting down or if something else is happening. So every weekend I'm improvising there during the mass, and that's many hours of music. I've been doing this for twenty years in the church now, and I play all types of music. I do stuff with electronics, and also with my iPad. People have also started to get curious about new music, and they gain a different way of listening from having heard so much of it. So that's also my room of experimentation, my experimentation studio, a little bit during the mass.

Lawrence: For lack of a better way to say it, the organ is having a moment. There's so much contemporary music being done, whether it's in the ambient world or modern composition. I first became aware of it maybe a decade ago. John Zorn really embraced the organ for improvisation, and that's some exciting music. So we have this ancient technology in this hypermodern context. I guess my question is, why?

Hampus: I think it's a combination of things. I mean, these are always cycles. So in five years, this moment will be over, but it also spurs a new generation. They seem to be all female artists, starting in Sweden with Ellen Arkbro. She released a record called For Organ and Brass, which is really incredible. She came to the organ not because she was interested in the organ; she came to the organ because she was interested in the tuning, and these baroque organs had this special temperament. She was studying just intonation with La Monte Young, so she wanted to explore this and the organ because the baroque organ could reproduce some of those sounds. Then this became a little bit like a trend.

So there are many others. There are several from Sweden, but also Kali Malone. There’s also Kara-Lis Coverdale and Sarah Davachi. They are also working in a similar way. There are also these people building some kind of strange organs with particularities. For instance, there are these artists doing it in Berlin—Sollmann Sprenger, who's built a more drone-like organ. They have also been doing experimental bass pipes that are based on loudspeakers from techno clubs that can produce really low and intense bass sounds.

Then there is another group, a collective called Gamut Inc., also in Berlin, who are working with organs automated with MIDI. Then there is Fujita from Japan, who has a very ritualized way of playing the organs. I guess that's part of the culture. I think many of those things emerged somewhat independently. There are just so many people doing exciting things now.

Lawrence: You have an interesting perspective, I think, because of the music you grew up with and around. You mentioned the club scene of the nineties, the techno scene, and, of course, the classical and conservatory training. You sit at this fascinating place where you can observe essentially the cultures of innovation and the cultures of tradition. I wonder what resonates for you across those cultures? Do you view it as a spectrum?

Hampus: Yeah, there's definitely a general fascination for the organ, for the instrument, from all these different groups. Then sometimes, you know, these experimental pipes may have more in common with electronic music. This neo-minimalism has more in common with pop or old minimalism, and it's a reiteration of this type of music. I don't know if they're so related to each other, but the music is related just because of the instrument, but not necessarily in how it's composed. But it's a great group of people, actually, and everybody's friends, which is really fun.

Lawrence: Yeah, I would imagine. Tell me a little bit about the next iteration of your collaboration with Stephen. Tell me what High and Low is and how it builds on what you've already done together.

Hampus: We were talking about this in the beginning, about high and low culture. We got an invitation to a commission for a new piece for organ and guitar. Then I just thought of this Kurosawa movie, High and Low, which is about a rich businessman who gets his son kidnapped, and it turns out that the kidnapper took the wrong kid, so he kidnapped his butler's kid instead. Then the whole movie is about the dialogue between high and low, in terms of the rich person, the butler, the kidnapper, et cetera.

When we got the invitation, I suggested we think about this movie and maybe get inspired by it. I think "high and low" also corresponds so well—for many reasons, actually. The organ is high up, the guitar is—we stand downstairs and play. We have the idea of high culture and low culture. There are the pitch things that we can play with in the piece as well. So it embodied all our concepts for this piece. That's how this title came about. [High and Low premiered after this interview was conducted, on September 30, 2025]

Lawrence: For someone who comes across your work for the first time, what do you hope they come away with in terms of understanding the pipe organ and sort of what it is and what it can be? Are you an advocate for the pipe organ as a contemporary instrument?

Hampus: Yeah, I would say so. I mean, if you come across this music and you like it, then I think there are big chances that this person is going to dig deeper into the organ and its music. The next step is that I hope people will discover other organ music. So I think of all the music that I love—we talked today about Xenakis or Steve Vai—and that this can influence people to go and listen to more music, discover things, and just get a broader perspective of music.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments