Bill Kopp has spent decades chasing stories as a music journalist, building a career on thousands of published pieces that dig into the artistry behind the sound. His new book, What's the Big Idea: 30 Great Concept Albums, showcases this acquired expertise and Bill's ongoing fascination with music's most ambitious and audacious storytellers.

I fell for concept albums at an early age. I often liked my rock and roll bombastic and with a touch of pretense. Concept albums fit that bill. But as I grew older and my tastes evolved (and I became both more and less critical of the rock music genre), I could no longer deny that albums like Dark Side of the Moon, Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Quadrophenia, and the like were touchstones I returned to. And that rock music could have both a head and a heart.

In What's the Big Idea, Bill extracted fresh insights through conversations with the artists who contributed to the records, rather than relying only on research and existing interviews. He spoke with progressive rock pioneers, indie innovators, hip-hop storytellers, and comedy troupe visionaries. This breadth shows his recognition that the impulse to tell stories through music is universal, crossing stylistic lines and generational divides.

Kopp appreciates both the grandiose and the intimate. He approaches Pete Townshend's rock operas with the same careful attention he brings to The Hold Steady's character-driven indie rock narratives. He understands that ambition takes many forms. The same impulse that gave us Tommy's sweeping mythology is also evident in Poe's Haunted. His writing recognizes that the "big idea" can be as expansive as a space opera or as focused as a meditation on loss and memory.

With streaming culture privileging individual tracks over album experiences, Bill makes a compelling case for the enduring power of sustained musical narratives. His book reaches across time, from 1967 to 2024, showing that conceptually unified works are not some past relics. The form has adapted to new technologies, new audiences, and new ways of understanding the relationship between music and story.

What's the Big Idea is one music lover's meditation on the need to transform experience into narrative, and music's unique power to make those narratives resonate in ways that words alone often cannot achieve. Bill shows that concept albums, at their best, represent music's highest aspirations, the moment when popular art reaches beyond entertainment toward something approaching literature, theater, and personal revelation all at once.

Lawrence Peryer: You've written that, as a kid, you knew you wanted to be a rock journalist. Can you trace that impulse back to a specific album or moment? Was there a concept album in your early listening that planted this particular seed?

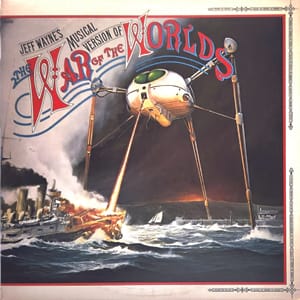

Bill Kopp: I started off buying singles, but quickly graduated to the role of ‘album consumer’ by about ten years old. From a very early age, I had been reading album reviews and was struck by the manner in which those reviews were as entertaining as they were enlightening. Thus inspired, those reviews led me to the direction of some more ambitious releases. The first conceptually oriented album I knew of was (no surprise here) Tommy. The first concept albums I purchased, though, were probably Klaatu's Hope (1977) and Jeff Wayne's War of the Worlds (1978), both released before I turned 15. Not at all coincidentally, both of those albums are featured in my new book.

Lawrence: After chronicling the rise of independent music with your 415 Records book and examining Pink Floyd's experimental years, what drew you to the concept album as a subject worthy of book-length exploration?

Bill: The albums explored in my book are a wildly varied lot in terms of genre, style, tone, and manner of execution, and those differences—the malleability of the concept format—have always intrigued me. I was interested in talking with the creators of those works to find out what they might have in common. And because I'm restless, I wanted to embark upon a project that was very different from my first two books.

Lawrence: How did your early experiences in marketing and advertising shape your understanding of how artists communicate ideas through albums?

Bill: When I was in the corporate world—and then slightly outside of it as a consultant—I used to quip that the ‘world's oldest profession’ is advertising and marketing! In some important ways, the practice of artfully winning an audience over to your way of thinking is shared by artists as much as it is by writers of ad copy. The methods and mechanics are different, but the goals aren't worlds apart. To take on another cliché, ‘build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door’ is utter nonsense. You have to make an appealing case. And with its big ideas, a concept album has to make a case for its own existence. The best ones do that.

Lawrence: In preparation for our discussion, I tried to find a comprehensive survey of concept albums, which led to Wikipedia's List of Concept Albums. A couple of things struck me: Jesus Christ, there are a lot of so-called concept albums, but also, many of them are ‘on the bubble’ in that they were either never declared a concept album by the artist (David Bowie's ★, pronounced "Blackstar," for example), while for others, I struggle to determine their distinction between a concept album and a record with some thematic through-line (like, say, the first Arctic Monkeys record). In your introduction, you mention that you are broadly inclusive in your own definition. Tell me about that decision.

Bill: On one level, a concept album is whatever the artist says it is; that decision is up to him/her/them. From my perspective as a listener, anything that holds together (or, at least, that's intended to hold together) in a unified manner—that's a concept album. Maybe the concept is a musical motif; maybe it’s Private Sorrow’s life story. Maybe it’s a band pretending to be another band (see: Beatles, Turtles, and yes, even “Chris Gaines”). It stands at the opposite end of the spectrum from “Here’s the most recent twelve songs I’ve written.”

Lawrence: You've chosen albums from 1967 to 2024—from psychedelia through hip-hop. What was your selection process? I love that you chose the Ghostface record, but I would have loved to have read you chopping it up with MF DOOM about MM..FOOD.

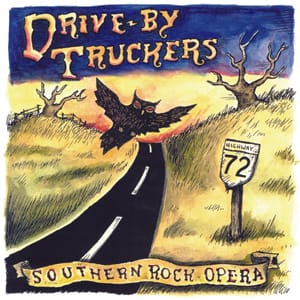

Bill: First, I chose albums that I truly enjoyed; I’m not here to make a case in favor of music I might respect but that doesn’t give me joy. Second, I made sure not to focus on a particular era to the exclusion of another; that’s why more than a third of the albums featured in the book are from 2000 and later. And there are even two from the ‘90s, a time when nobody wanted to know; just ask Pete Townshend and Captain Sensible!

Lawrence: Can you walk me through your research and interview process for one particular album in the book? How did talking with the artists change or deepen your understanding of their work?

Bill: In every case but one, I spoke with the primary artist who made (wrote, recorded) the album. The exception was Joe’s Garage. Zappa died in 1993, and I had met and interviewed Ike Willis many times and knew he’d be a great source of stories and context. In general, I’d schedule an interview, nearly always via Zoom, so we could look each other in the eye. I’d start by outlining my book’s er…concept to the interviewee, and then let the conversation go wherever it wanted to go. I had plenty of questions to fit most every eventuality. Some wanted to talk about the sessions; others, the inspirations, or the songwriting. A few asked me for a follow-up interview to dig even deeper into the subject. Along the way, I gained a better understanding of what the artists wanted to communicate, and why, and how. I hope the book is enlightening to readers interested in the same things.

Six of the albums featured in "What's the Big Idea'

Lawrence: I give a talk on the history of creativity and innovation, and when I am speaking to a music-knowledgeable audience, I ask if anyone knows the first concept album. The Wall, Dark Side of the Moon, Tommy, and Quadrophenia always come up. Sometimes Ziggy Stardust. Never In the Wee Small Hours, but the audience is always tickled to hear the story. Tell me about Frank Sinatra and the birth of the concept album, as well as his repeated return to the genre. Bonus points if you can talk about Watertown while you're at it.

Bill: Ah, yes...Watertown. In fact, that and another album were left out of the book for overlapping reasons. In 1968, Frank Sinatra – as you point out, arguably the originator of concept albums – released Watertown. A song cycle of ruminations upon love lost. “Saloon songs,” as Sinatra called them, collected together for an album’s worth of reflection and misery. It’s a shame that Sinatra was rewarded with critical and commercial indifference when he made Watertown. These days, it’s undergone a well-deserved reassessment. Shortly thereafter, The Four Seasons – by most measures, an equally unlikely source of conceptual material—made The Genuine Imitation Life Gazette. At the creative center of both albums were Bob Gaudio and Jake Holmes; they’re also pretty much the only surviving personnel from those projects. Though I was persistent, neither of them was available even once during the time I was working on the book. Maybe next time.

Lawrence: When you spoke with Captain Sensible, he recommended the concept album format to all musicians as "a massively creative and fun way to make a record." Having now interviewed artists behind 30 of them, do you see concept albums as a natural evolution of artistic ambition or something more fundamental about how humans tell stories?

Bill: Yes, I really do see concept albums as a sturdy medium, or platform/structure, upon which to tell a story. Even short pop songs can be stories; look at Elvis Costello's “Welcome to the Working Week.” And it’s only 82 seconds long! But for bigger ideas, concept albums provide an expansive metaphorical canvas upon which to paint. Conversely, while some artists have approached the form as a vehicle to legitimize themselves (Kilroy Was Here, I’m lookin’ at you), those sorts of ham-fisted and self-conscious endeavors are often risible disasters. “Domo arigato” indeed.

Lawrence: You've written extensively about reissues and the importance of physical media. How does the concept album format interact with modern streaming culture, where albums can be shuffled or played piecemeal?

Bill: You’re shining a light on a serious conundrum here. Some of the artists I’ve interviewed (for the book and well beyond that project) despair of the listening public’s return to a singles mentality. Some have even pledged to abandon the idea of making concept albums – or even albums of any sort – in favor of one-off track releases. At the other end of the spectrum, you have Steve Kilbey, who only recently entered the concept-album world with The Hypnogogue, The Church’s 26th album. He told me that going forward, he’ll probably only make concept albums. Like any artistic medium, concept albums are not for every taste. But I believe there will always be an audience for the form.

Lawrence: I am curious about your work on live events, listening to and talking about albums and music movies. How has this work informed your writing, and vice versa?

Bill: I never did a live event prior to 2012, and my second one was six years later. In recent years, I’ve done dozens, and I love it. There’s a delightful give-and-take that happens during in-person events, and experiencing that has informed the way that I think about my writing. More specifically, I have a tendency in my writing and speaking to insert interstitials – you know, like this one here – that (some say) interrupts the flow of thought and clear communication. Since I’ve made public speaking a bigger part of what I do, I employ those bits less frequently now. But perhaps still too often.

Lawrence: Having written thousands of pieces about music, how do you maintain fresh ears and genuine curiosity after all these years?

Bill: Two ways. First, I try to maintain my enthusiasm for discovery. That means seeking out artists and music that are new to me. In preparing this book, I listened to several albums for the first time and discovered that there was quite a bit more depth to them than I would have expected. And second, I approach even familiar music from new angles. That often means finding the story behind the music.

Lawrence: What concept albums are you hearing in contemporary music that suggest the form's future? Are there artists working today who you think will be in the sequel to this book 20 years from now?

Bill: There are many, many current artists making intelligent, effective use of the form. The Mountain Goats did one not long ago. Janelle Monae has done a few. I believe—and hope—that new concept albums will arise as long as the album format exists.

Lawrence: After immersing yourself in all of these concept albums and their creation stories, what is the Bill Kopp Unified Theory of the Concept Album? What makes this construct so enticing that artists keep returning to it?

Bill: I think that Pete Townshend summed it up best when he told me about an interchange in the early days of The Who. Fans met him outside a club in Shepherd’s Bush and explained to Pete how much his lyrics meant to them. He remembers thinking, “Wow, they have found something—something far, far more vital and important and moving than I intended—in this deliberate vagueness of the story that I wrote in a song lyric.” At that moment, he decided he wanted to be more than a songwriter; he wanted to be a storyteller. And concept albums provide that opportunity in a way that an individual song can’t always accomplish.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmBill Kopp

The TonearmBill Kopp

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments