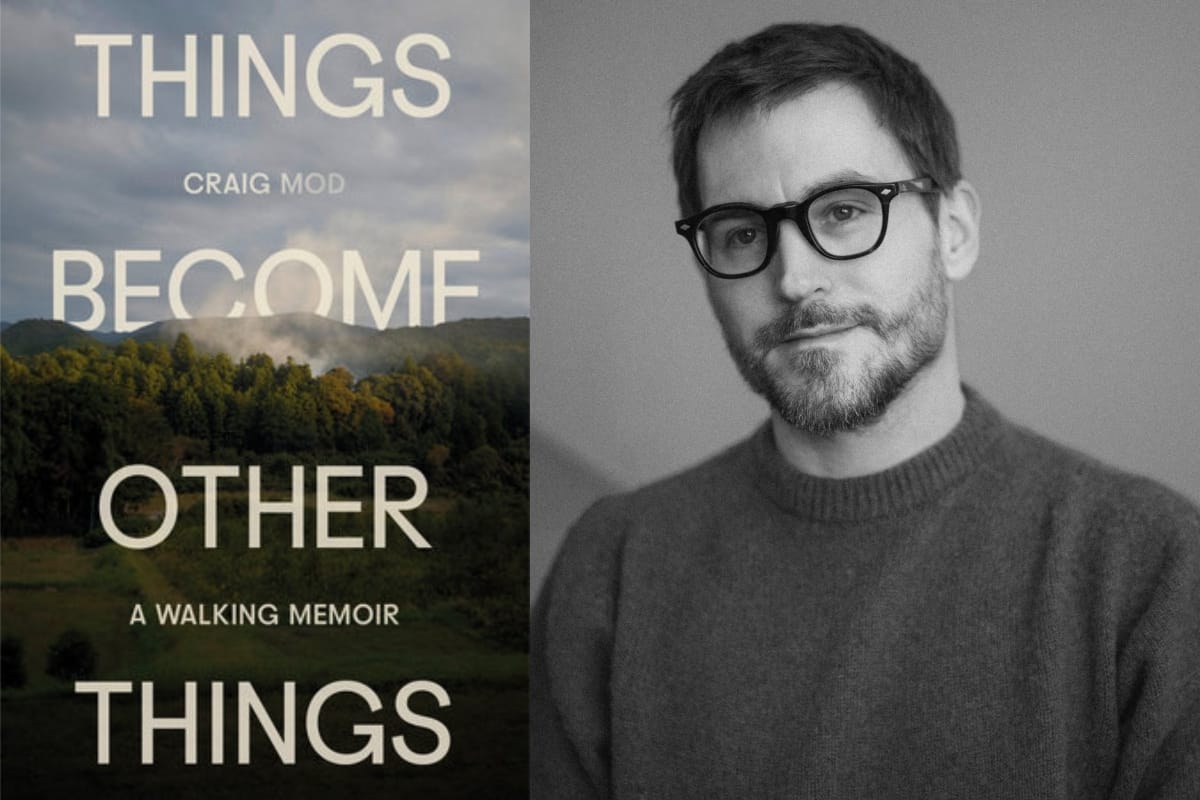

Craig Mod navigates the physical and digital worlds with rare intention. As a writer, photographer, and publisher, Mod has created an interconnected suite of creative outlets that free him from editorial constraints. Since 2019, his SPECIAL PROJECTS membership program has enabled him to pursue writing that interests him most, while supporting public-facing work available to all—a blueprint we’re very much interested in here at The Tonearm. This model of creative independence has yielded some of his most productive years, resulting in books like Kissa by Kissa (2020), which chronicles his walk along the Nakasendō from Tokyo to Kyoto, and now his latest work, Things Become Other Things.

The rhythms of walking thousands of kilometers across Japan since 2013 have become central to Mod's creative process. These long-distance journeys along ancient highways and pilgrimage paths serve multiple purposes—meditative practice, historical exploration, and cultural discovery. Through projects like Koya Bound (2016), a photographic collaboration with Dan Rubin and Leica Cameras documenting the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage routes, Mod has established walking as both subject matter and methodology. This physical movement generates the mental space where ideas can develop and collide, away from digital distractions and algorithmic inputs.

For Mod, physical books represent the ultimate creative artifacts. "I've landed on the digital stuff isn't real," he noted in conversation. His commitment to print reflects a belief that books demand complete attention in ways other media cannot match. They require finalization in a permanent form—a pressure that digital publishing lacks—and they endure physically in ways that online content may not. This reverence for the printed page exists alongside his extensive digital practice, which includes newsletters, podcasts, and photography. Mod doesn't reject digital tools but sees them primarily as means to produce lasting physical work.

Craig Mod joined host Lawrence Peryer for a fascinating episode of the Spotlight On podcast. In this conversation, Mod discusses the unexpected origins of his latest book, Things Become Other Things, which he self-published as a boutique ‘Fine Art edition’ before its reworking and mass publication through Random House. Mod also dives into his processes and the relationship between memory and friendship that forms the book's emotional core. He shares insights about finding one's unique voice through persistent practice and the courage required to embark on creative projects without guaranteed outcomes. "I have five books I want to do. I know the next five," Mod told us, demonstrating the clarity of vision that sustains his varied artistic pursuits, whether walking Japanese pilgrimage paths or establishing a dedicated studio space for the first time in his life.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Be the Only

Lawrence Peryer: I was listening to Rick Rubin interviewing Malcolm Gladwell the other day, and they had a little piece of their conversation that made me think of you. Ruben asked Gladwell, “Do you ever have projects or themes for your books that don't flesh out?"

Gladwell answered that he has so many outlets that it’s rare for him to be unable to use an idea. He has numerous vehicles and outlets—from podcasts to essays, book chapters, and so on—he can effectively convey his ideas through one of these outlets.

Craig Mod: That's interesting. Like Gladwell, I also now have enough outlets that I've deliberately concocted on my own. That's why the membership program exists. I mean, that was essentially a response to not having an outlet. I was deep in a year of working on an essay for The Atlantic, and then it got kind of canned—I got ghosted. It just didn't work out, and that's what catalyzed the start of the membership program and the Ridgeline newsletter. I didn't want to be in a position where I felt beholden to some random editor's whims on the other side of the world.

Since then, I've been lucky in that I can usually find a place for something if I need to. But until six years ago, I struggled with not finding homes for things or having to abandon certain projects. That was probably for the best to a certain degree, because these things weren't necessarily the greatest versions of themselves.

I've talked about this before—from 2011 to 2017, I spent time working on a novel that was based on burying my dad. That didn't get published, which was probably for the best, and it was rejected many times; however, it allowed me to participate in all these writers’ residencies. So that project got me into all those things. Even though it didn't have a classical piece of output in the sense that it didn't become a published book, it was a very useful tool for almost all of my thirties. It was a great training ground, and I met a bunch of interesting people and still have good friends to this day through that project.

So even the things that don't make it out into the world in the forms you expect them to, obviously have a lot of good, and this was one of them.

Lawrence: Yeah. You'd be very hard pressed to call that a failed endeavor.

It's interesting that you tell that anecdote, though, because I've had instances in my own life where younger people have asked for advice about getting into creative fields. I've always said, just make your own work. And that could be like a 30-second short—you don't have to make a feature film—but just have something that you can start and finish. At the very least, you've practiced with your tools, which is invaluable. But you've also learned how to finish something, and that's pretty powerful for someone who wants to be creative.

Craig: It's everything. And that's what most people don't experience because it's so easy to talk yourself out of finishing stuff. Kevin Kelly has a great quote. He says, "Don't be the best. Be the only." And I love that. So, that’s another thing to keep in mind—if you’re working on something or feel overwhelmed creatively, stop trying to be the best illustrator or the best Miyazaki-style illustrator or animator. Figure out what your weird, unique overlapping of skills and life experiences can make you the only of.

I think exactly like you say: choose projects that you can complete. There's a reason they call it a practice. That's all you're supposed to be doing, essentially, until you're dead. Just keep practicing, practicing, practicing. So I think that's really good advice.

Lawrence: I wonder if Kevin Kelly got that quote from Bill Graham. That's what he used to say about the Grateful Dead. They're not the best at what they do. They're the only.

Craig: Yeah, he probably did. It's a great line. Although I don't think Kevin was a Deadhead, but he was certainly in the scene peripherally at that point.

I think for young artists, creators, it can be so hard to have that kind of faith to commit to a project and believe that something interesting is going to come out of it. The reality is, for the most part, interesting things aren't going to come out of your projects.

There's the Ira Glass quote about taste and skill, taste and talent, where your taste, when you're young, always outstrips your talent. You spend a lot of your time as a young artist trying to rectify, trying to pull up your talent to match your taste. But it can be so discouraging early on. A lot of people just get frozen and stop there. So I empathize when I think about my twenties and the work I did in my twenties—it was a huge constant struggle of not being able to hit the taste points that I wanted to hit, but you just have to put in the practice.

Where the Heart Feels Pulled

Lawrence: It’s striking in a lot of your work how the themes reveal themselves to you. So specifically with Things Become Other Things, this sort of intersection of walking and memory and friendship, the veracity of memory, or the reliability of memory. Do these things emerge and you recognize them, or do you have this conscious intention that you want to craft a narrative that conveys this?

Craig: I would be hard pressed to say it was a conscious, deliberate thing. I think a lot of it comes from what I’m reading, who I’m inspired by, or what books I feel moved by or drawn to. There’s also something about the voice. So it's almost less about themes explicitly and more about where the heart feels pulled towards.

That sounds very woo-wooey, but I've just spent a lot of time reading all sorts of different books, and certain things speak to me more than others. Annie Dillard, in the way she writes about nature and writes about being in the world, is a huge influence. I don't think she has a deliberate process. When she was writing Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, she was just there. She was also really young. She was around 25 or 26 when she wrote that.

So I think I'm more drawn in that direction. Standard narrative has always been really hard for me. I'm uninterested in plot. I'm uninterested in explicit story. That's why a lot of what I do is vignettes. For me, it’s not about, “Oh, are we hitting these plot points, and does it take the reader to this place and that place?" It's more about just the energy and the feel of almost each sentence and then chapter by chapter, rather than necessarily the whole.

I think Things Become Other Things is probably the most cohesive thing I've ever written, in the sense that there is a clear story and a distinct reveal happening. There is a certain structure to it in terms of acts. However, it was a very organic and unexpected process.

I think the walks are beneficial for me as well, since having all the logistics set up allows me to be one hundred percent focused on just walking, and I don’t have news, social media, podcasts, or anything else running in the background. As I walk, that physical act just gets the mind moving, and stuff tumbles out. As I walk, I dictate. I'm constantly dictating. And that's how I'm able to do two, three, 4,000 words a night after walking for eight hours. Then, out of that, you can start to find themes.

I remember when I started working on Things Become Other Things, about four and a half years ago now. I went through all the writing I had done during the walk and printed it out. Then, I literally cut out sentences and paragraphs from the printouts that felt most resonant to me. I just put them all on the ground and shuffled them all up, and started going through them again. That allowed me to look at the themes that were naturally emerging during the walk in a way that was kind of divorced from the explicit linearity of the walk itself.

So I was just trying to get fresh eyes on what we were feeling, what things were kind of burling up as we were walking. And that became the genesis for some of the first drafts. Then, [my close friend from my teenage years,] Bryan, started to sneak his way in more and more. An editor I was working with for the [original] Fine Art edition, Ali Chance, really started helping me pull on that thread. That's when that expanded into more of a thematic part of the book. Then Molly Turin, my editor at Random House, really helped flesh that out even further.

The way the Random House edition opens is that it begins with a chapter I don't get to in the Fine Art edition until three-quarters of the way through. I think to get to that chapter took me all the way to that point, and then realizing that chapter felt like a pivot for the Fine Art edition.

Annie Lamott, in Bird by Bird—all these books about writing, On Writing by Stephen King—it's like, if you have something great, play that card immediately. There was a certain energy I was getting from that shift in the book, three-quarters of the way through the Fine Art edition. I was like, "This is how the book should just start. This whole book is just a letter to Bryan."

That's kind of what happens. I'm tiptoeing, tiptoeing, tiptoeing in the Fine Art edition. Then, three-quarters of the way through it shifts to this letter to Bryan, and then the whole last quarter is kind of facing him. And I was like, "The whole book should be facing him. Screw this. That energy—I want to imbue the whole book with it." Once we did that, which was like this major surgery, it gave the book space to be so many other things.

Lawrence: It's interesting because it doesn't sound convoluted to me. It sounds like a very unique and special experience to be able to revisit a work, rework it, re-engineer it, expand it, and rediscover it.

Craig: No, it wasn't a disaster, but it was just so ‘improv jazz,' you know? Nothing was planned. It was just tap dancing here and there and avoiding these pitfalls and these traps. I think you can over-revisit something, too. That was always top of mind. I would say there's a 0.00000001% chance—I won't say there's no chance, but there's almost no chance I would ever want to come back to this and do something with it again. I am so sick of this manuscript and so sick of this story, I think, and that's actually how you want to feel when you launch a book. That means you have just wrung and wrested from it every drop you could possibly get from it.

Lawrence: That process makes it feel like the book is a piece of your soul, a piece of your intellect, like your lived experience. It's fascinating.

Craig: Yes. And at the same time, I'm trying to be as flexible as possible and not be like, "Okay, these are the only things I can do." I'm also trying to build in these different timeline-scaled projects. I’m now working on a new self-published photo book called Other Thing, and I’m going from shooting it to having it in people’s hands in two and a half months, which is pretty cool. I love that I’m doing that, and that just makes me think, "Why am I not doing at least one of these a year?" with other scale things happening in the background.

Lawrence: Sitting here and watching you speak about this process and what’s going on with the photo book, it’s clear that you come alive talking about it. One can feel the enthusiasm you have for the project. It's very palpable.

Craig: Well, I think what's exciting is it's surprising to me. This didn't exist three months ago—none of it. It was just this impulse. It was like, "Yeah, I should probably go do this." I didn't have time to do it. I had every excuse not to do it.

Other Thing is dedicated to my friend Enrique, who passed away in November last year, who was my roommate when I lived in California in 2010, 2011, and 2012. He was just 38, so really young. His memorial took place while I was on the peninsula shooting for the book. I had just brought my stepdaughter to boarding school in New Zealand a couple of weeks before, in January. I was exhausted from that.

I felt so bad about it because I wanted to be there with everyone celebrating Enrique's life. So, what I tried to do was, when I was shooting the photo book, I just tried to keep Enrique in mind and embody his positivity, joy, love of life, and connection. I tried to think about that while I was shooting all these people, and I felt really bad to miss the memorial. So the photo book is dedicated to him. I think Enrique would be psyched that I was doing that, and he'd be like, "Dude, don't—I'm dead. You don't need to come to my memorial."

So anyway, just the fact that this project has all these different facets to it, whereas three months ago it didn't exist—it's exciting. There's always something like this right there to be done. It's almost theological—you have to build up this belief system that you can go out there, you can do it, you can find it, you can shoot it. If you put in the energy, you're going to find something interesting.

Going to the peninsula, doing this project two months ago, was a huge act of faith. I didn't know who I would see or meet, or if we would get any good photos. I was shooting mainly with film, too, for the first time on a big project like this. That was terrifying, not knowing if the cameras were even working properly. Are the shutters firing off in the right way? You can't check anything in the moment.

So just having this tremendous amount of faith going into it, and then also keeping Enrique in mind and all that stuff—it was pretty powerful. And then to come out of that, have a bunch of work I'm proud of, forming these new relationships with photo studios and the scanner around the corner for me and all that stuff—it's exciting.

We're Making Books

Lawrence: Talking about physical books and the Fine Art edition has me curious about your relationship with or thoughts on analog and digital mediums.

Craig: For me, I've landed on the digital stuff isn't real. Nothing happening on the internet should be considered permanent or should be considered in and of itself a final artifact. That's why, with my members' stuff, I always say, first and foremost, whenever I run a board meeting, the purpose of this program is two things. We're making books, physical books—that's the number one purpose of this program. And then number two is education. That's why I run the board meetings and stuff like that, but education directly comes out of doing things that make me better at making the physical books.

The reason I've landed on "the only thing that matters is the books" is because that really does feel like the place to have the best conversation. By focusing on the books, I want people to engage with this stuff with their full attention. I want to have conversations with folks who are totally present. And I think a physical book is still maybe the best way to do that, even more than a movie, because you turn a movie on, and people are still reaching for their phones. You can have the ambiance of a movie, and you're still doing all this other stuff with your attention. Whereas a book, if you're not fully in it, you're not in it. You can't multitask with a book.

And so I think it’s a perfect, focused piece of technology or media. In that way, it's exciting. All of this other stuff is supplementary in my mind, and all of this other stuff will be gone. It will disappear. The archives, the digital stuff, are so tenuous. Still, if you put a thousand printed books out in the world, unless someone really hates you and hunts down every copy and burns every copy, chances are that artifact is going to be in the world forever, for hundreds of years. And I don't think there's any other piece of media that you can say that about.

End-to-end, books force you to collate your thinking because they are so final. There isn't a way to go back to them and revise them in the form that they're in. Yeah, you can do things like I've done with the Random House edition and kind of do additions and stuff like that. But that's it for that form of the thing. Because of that, it creates this sense of deadline and a sense of refinement that online stuff, digital stuff, doesn't bring to the table. It doesn't bring that sense of urgency.

That also makes it exciting for me, in the sense that this is the best version of this thing I could have possibly done. And here it is, immutable. Here it is in the world, in thousands of copies, hopefully tens of thousands for this Random House edition. It's probably going to be here forever. That feels like it respects the project in a way that many digital-only things don’t.

When I think about YouTube and the people on YouTube, I think about how much effort is going into these channels and how much time and production are being put into them today. It kind of breaks my heart that there is no real archive of this stuff. With DVDs and Blu-rays, at least you had some physical media, even though it's not very robust. With prints, such as 35-millimeter prints, if they are archived properly, they can last a long time. But a lot of this YouTube stuff is just creative energy going to this place where it sort of evaporates.

Lawrence: It’s even worse with TikTok and anything you create in-app.

Craig: Yeah, I think the only way to think about those mediums is to assume they're temporary. I'm friends with Derek Mueller from Veritasium, and Derek has created this incredible TV show entirely on YouTube. And I do wonder, is there a way we could archive this? Is there a Veritasium book that he should make, somehow distilling many of these great videos and the amazing infographics he’s produced into a printed archive? That feels like it would honor the work he’s done in a way that simply existing on YouTube doesn't.

The scale is different, obviously, and you have to think about that, and you have to keep that in mind. Derek's reaching hundreds of millions of people on YouTube, but what is the quality of that attention? What is the quality of that conversation? I think those are important questions to ask.

For me, I'm grateful to have this analog practice, which I've been doing my whole life, or my entire adult career, with physical books. And so for me, it's really intuitive, and I do think physical books are kind of a perfect analog instantiation. I think they’re a perfect piece of technology to a certain degree, and we’ve really dialed in, perfected it. And we’re lucky to have the postal system.

It's insane to me that, for all of the fractured nature of politics today, the world has agreed on postal systems functioning everywhere that basically isn't a war zone. For $30, I can teleport this object that weighs almost a kilo, kind of big and onerous, and it arrives in perfect mint condition anywhere in the world. It's essentially a teleportation device.

Lawrence: You’re currently on a US book tour for Things Become Other Things. When that ends, you go back to Japan, you sit down, you exhale. Then what?

Craig: I have no idea. I just know I'm going to need recovery time. I'm setting up a new studio, and that's directly in service to my next projects. And so that's sort of my goal for July and August, and to do as little travel as possible. I hope to get this new studio space dialed in in a way that it's all—look, I could do these projects in a closet if I needed to. I don't need a perfect workspace to get these things done. I think it’s important to acknowledge that.

But it would be amazing—this would be the first time in my life that I have a true, fully dedicated project space. I'd like to have some quiet time where I’m not working on a book, not doing interviews, and I’m just getting the studio space built out in a way that feels great, reflecting on these last few months. So we'll see.

Visit Craig Mod at craigmod.com and sign up for his newsletters Roden and Ridgeline. Purchase Things Become Other Things from Bookshop.org, Powell's Books, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, or Apple Books.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments