Kramer—when you hear the name, get it right. We're talking about the musician who was one of the central figures in the Downtown scene 30 to 40 years ago. He was shaping and defining the musical culture of the era from both the front and the back. He was a member of post-punk/no-wave/avant-garde bands Shockabilly and Bongwater; he played with John Zorn, he toured with the Butthole Surfers, Ween, and Half Japanese, and those are partial credits. Behind the scenes, he founded the Shimmy-Disc imprint, took over and ran the Noise New York recording studio, and was instrumental to the careers of Daniel Johnston, Galaxie 500, GWAR, Low, and other bands and artists.

This was never easy nor lucrative, though through the trials and tribulations of the decades, Shimmy-Disc and Kramer's music-making have survived. For a time, he even worked at the James Randi Educational Foundation, which debunks claims of psychic phenomena. Shimmy-Disc has recently released a duo album with Laraaji, revived and redone Allen Ginsberg's album The Lion for Real, and just this year Kramer himself has his name on three scintillating new releases: Skantagio from the Squanderers trio of Kramer, Wendy Eisenberg, and David Grubbs; and the dream-like albums Interior of an Edifice Under the Sea with Pan American, and his solo ...and the crimson moon whispers goodbye, a gorgeous, enveloping ambient soundscape of waves of drones, murmuring voices, what seems like the shaking and motion of objects, and more.

A recent interview about that last album turned into a discussion about audience perceptions, Daniel Johnston and Morton Feldman, the nature of musicianship, the mysteries of "why," and much more.

George Grella: I'm gonna do my best to confine this to the topic at hand, because your career is just . . . there are too many things to follow!

Kramer: Yeah, I think that's the problem.

Grella: We should all have these problems . . .

Kramer: Still, it would be so nice to earn a living. And I'm also trying to make films now, and for the last ten years. Just this past year alone, I've come very close. In fact, as soon as I get off the phone with you, I have to call Bruce Dern to catch up with him on a film we're trying to make, and this is the worst time for film financing in decades.

You and I have adjacent experiences in getting our work out. You know, I always think, "This [forthcoming] record I just made with Thurston Moore is going to change my career." And I thought the same thing when I produced [the Urge Overkill recording of Neil Diamond's] "Girl, You'll Be a Woman Soon" for the Pulp Fiction soundtrack. Instead, it was the beginning of the end of my major-label relationship! And I'll tell you that very quickly, I had three different managers after Pulp Fiction came out, and they all dropped me within a few months. And the third one, a good friend of mine, said that, "There's nothing I can do for you. I can't keep taking 15% of your earnings if I'm not getting you any significant paying work." And I said, "Okay, no problem, we're still friends, but since we're friends, tell me what the fuck is going on?"

He said, "Well, you produced something that sounded exactly like it was recorded in 1966," and I said, "Yeah, that's what I was trying to do!" And he said, "Well, the problem is that it's 1994 and they're not looking for things that sound like they were made in 1966, they're looking for the next Butch Vig." That wasn't just a great song in a great movie . . . it was the song in the fucking movie! And it killed me. It just did. It ruined the little major-label work that I was getting.

But let's not talk about the music business. Let's talk about music. They're two different things.

Grella: Relevant to that and the new album, and also this recent flurry of music that you're putting out, what's the challenge of trying to get people to understand what you do?

Kramer: Oh, I don't want them to understand it. I want them to experience it. If I understand things completely, I get bored. And with all of the great music that's happening nowadays—I'm not talking about the music industry, but about the arts—so many doors have been opened up. There are people who were working in diners and at the post office 10 to 20 years ago who are now earning a living making experimental music, doing festivals, tours. And I think it's amazing what's drawing audiences now, listeners are getting more demanding and more interested in hearing things unlike anything they've ever heard before.

To me, they're not trying to figure it out; they're just wanting to experience something. People don't come up to me after shows and ask, how did you do that? I want them to wonder, why did I make that choice? And if you ask those kinds of questions, the answers really come from within. I don't know if any of that makes sense, but I'm really into just presenting things that are different, and nowadays I'm doing that.

There are so many artists now working with field recordings, and I love what they're doing, but I have no personal interest in introducing field recordings into my work. I still want it to be instrumentation. I want musical instruments as a starting point. And that means pretty much everything. So those are the kinds of things that interest me the most. Now, if you're talking about ambient music, that really started with John Cage and "4'33"." It's not site-specific work, but site-sensitive; the sound of the environment is the music. And Morton Feldman did Rothko Chapel. When I found that LP when I was just a kid, I thought, this is it. This is what I want to be involved with in music.

I was playing with Zorn for many years, improvisational settings, and then he got very active and complex, and he began to require the kind of musicianship in his ensembles that I couldn't really offer him. You know, I'm a failed classical organist and a self-taught bassist and guitarist. Dexterity is not really my forte. I'm a thinker. I think about silence. And then La Monte Young, and of course, Pauline Oliveros, who took it to its apex. If I had to drop a few names, those are them, and Gavin Bryars, of course.

Grella: Have you been doing a lot of live performing recently, where you're encountering these audiences?

Kramer: Well, more in the last year than I had in the last twenty. I've been lucky to be able to perform in front of deep listening audiences, with [Squanderers] and solo. I've been composing, recording, playing, pretty non-stop for the last few years.

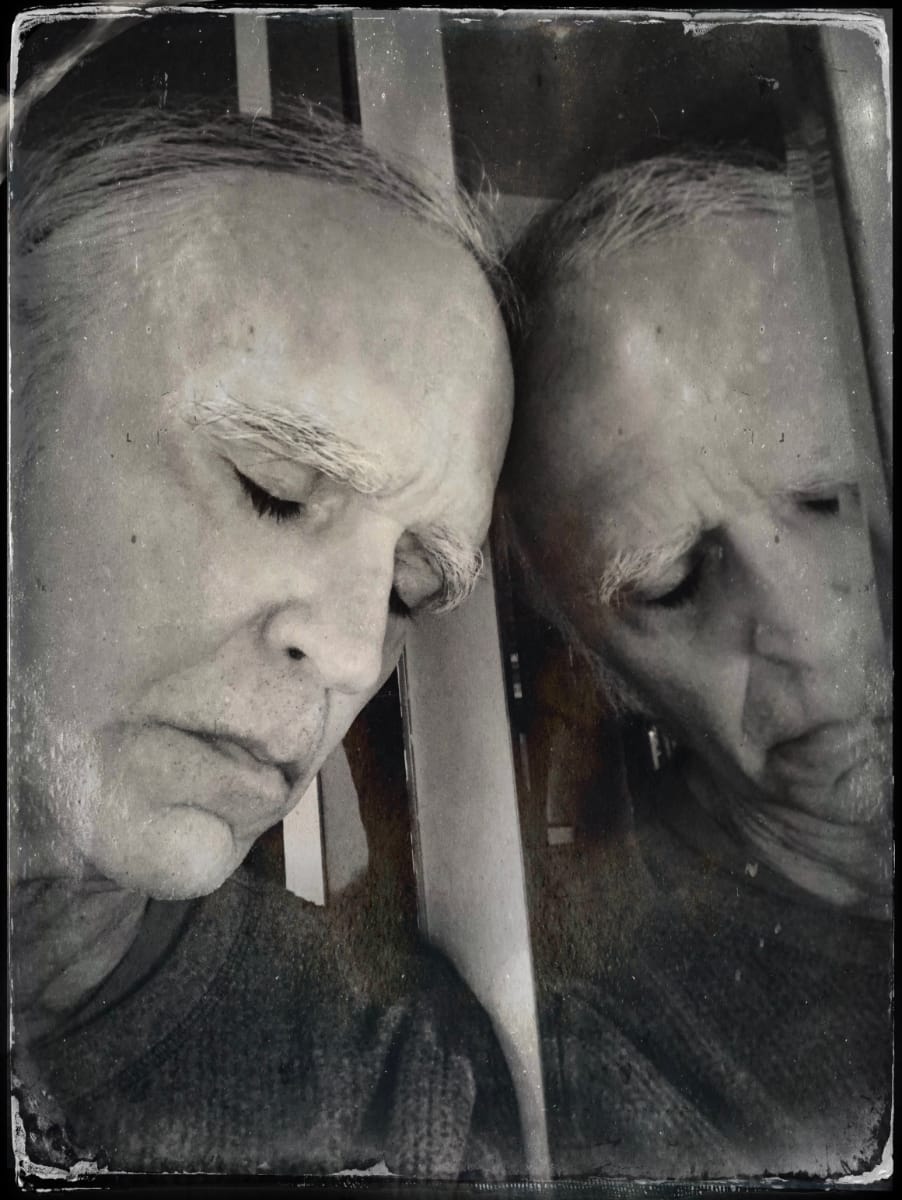

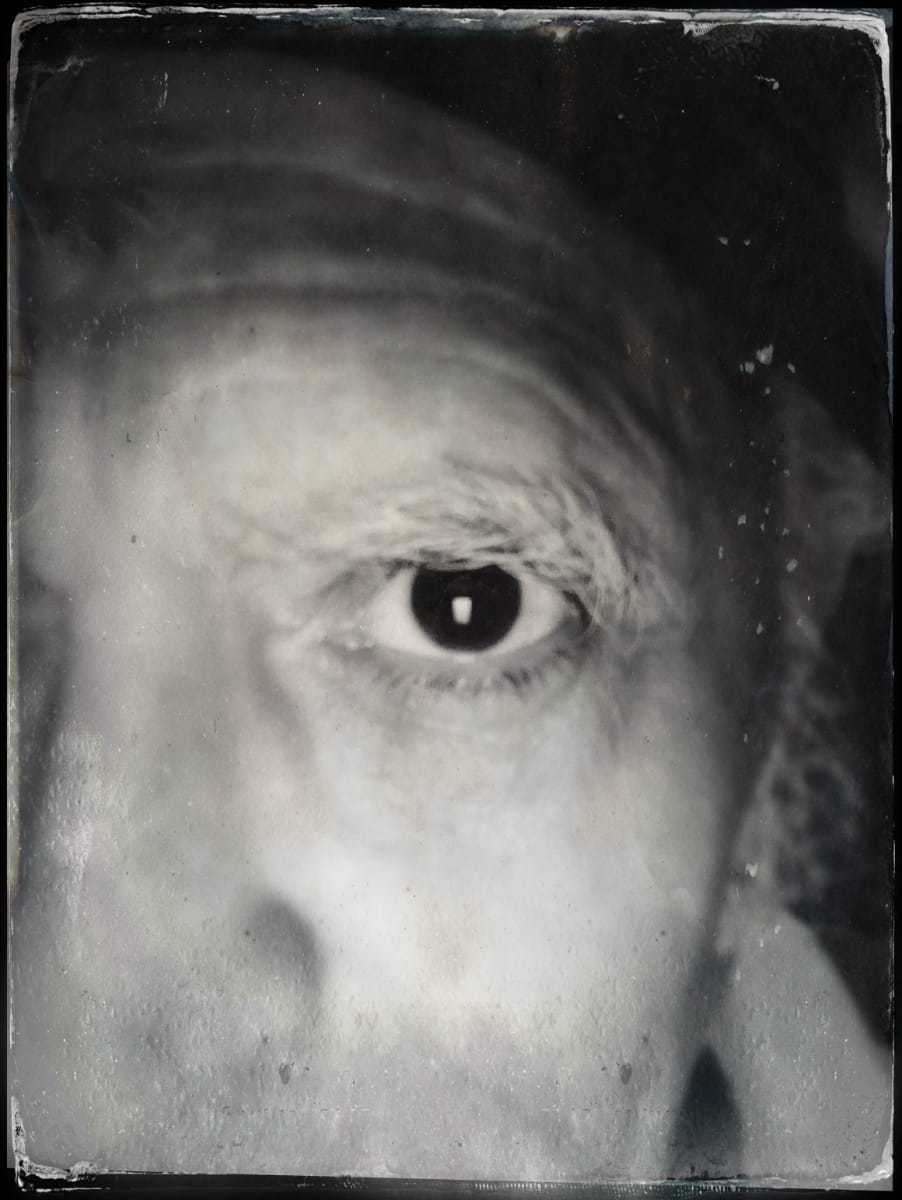

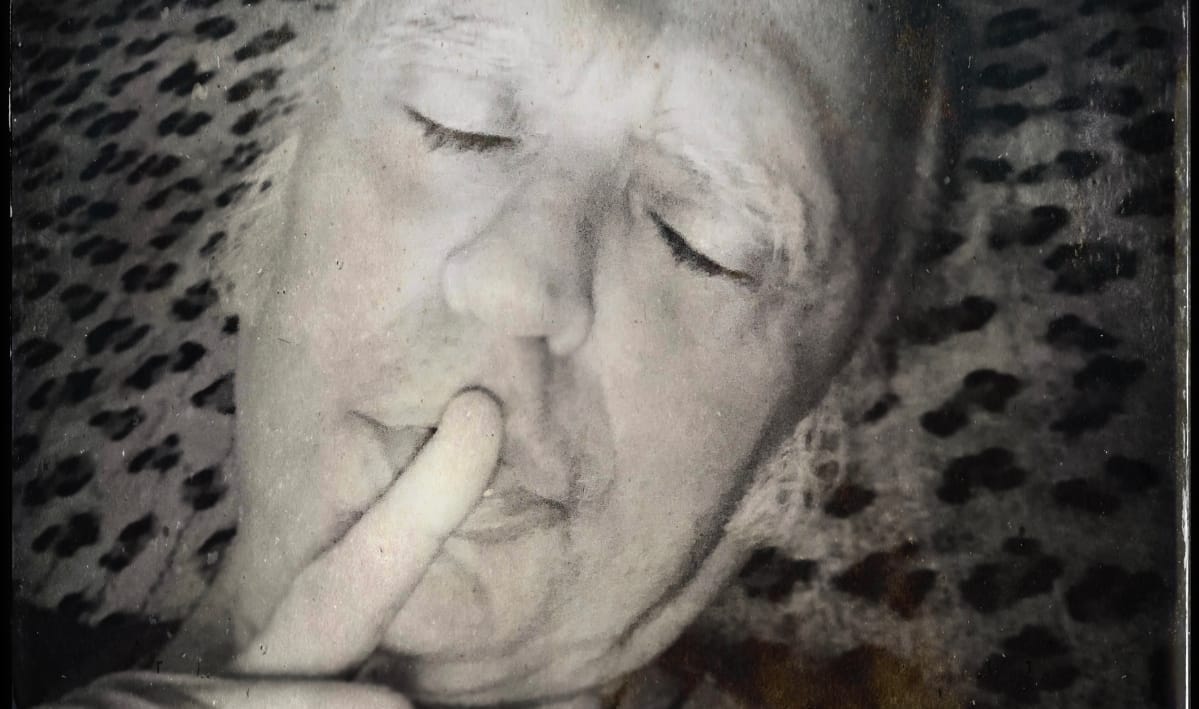

Self-portraits by Kramer

Grella: The Shimmy-Disc catalog you have up on Bandcamp, you've got all those Daniel Johnston recordings up on the page.

Kramer: Yes, thanks to a deal that I made directly with the Daniel Johnston Estate, with whom I remain very close. I mastered all of that material Daniel recorded in his home on cassette in the 1980s, so it's actually listenable now. That was a hell of an experience. I mean, a lot of those cassettes, the left channel was pure tape-hiss, and the right channel had Daniel's voice like a mile away, and the piano up close, or vice versa. So it was a fascinating experience mastering, oh, about 100 hours of that stuff, and it had to be done on a deadline, too, which meant I wasn't able to do anything else for a couple of months.

Can you imagine listening to Daniel Johnston all day, every day, for weeks and weeks and weeks? It had some negative effect on me. Not all of his songs are about speedy motorcycles and friendly ghosts, right? Most of his songs are about the things that scared the shit out of him and everyone else on this planet: evil, mortality, nobody loves us and nobody ever will, etc., etc., etc. So it was harrowing work at times, but now I look back on the process with a lot of love and heaps of gratitude for having been trusted with such an important job, because these are the definitive masters. This is what people will be listening to for years to come. It's such an important archive, and those recordings never sounded better.

Grella: You mentioned Rothko Chapel, listening to that album . . .

Kramer: It changed my life.

Grella: A light bulb went off in my head about the new record, which tickles things in my memory from my own past musical experiences. Even though it's your own thing, it fits into that Rothko Chapel space.

Kramer: Well, it's not the same space, but it's certainly an adjacent space. Was I thinking about Rothko Chapel when I made ...and the crimson moon whispers goodbye? No, I clear my mind. It's a very, very meditative process, solemn. How do I describe this? Eno said something many years ago. As a matter of fact, I think it was one of the Oblique Strategies cards. It said, "Honor your mistakes as though they were hidden intentions."

Grella: The Stravinsky thing, too, where he says there are no mistakes.

Kramer: I didn't know that Stravinsky quote. But what Eno was saying was that, at least in my opinion, there are multiple layers of consciousness. And to tap into them, the deeper they lie. You have this layer just below your consciousness, where you think ideas come from, but most people don't realize there are multiple layers, and very often, a mistake is a hidden intention. So I've found a way to trust myself enough in the performance aspect of recording and composing. I don't sit down and compose; I sit down and improvise, and the works come together. I will perform for 45 minutes, sit and listen once, and then perform again alongside it, or like a shadow, so to speak. And after a couple of weeks, you start stripping things away without trying to do too much choosing. And it really is as simple as what sounds good, what sounds original, what doesn't sound good, what sounds like I've heard before. I don't want to recycle or repeat what's already been done.

As long as I trust the process enough, and I'm in a good state of mind, I find that I can create something that really doesn't sound like anything else. So spiritually, sure, Rothko Chapel, but it wasn't something that was anywhere near the front of my mind while I was recording. But when I was all done with it and had listened all the way through with my wife beside me, I turned to her and said, "I finally got my Rothko Chapel." There's also a little bit of Sinking of the Titanic in there, I think, especially in track four. Again, these things were not intentional, but anytime something like that happens, where the results give me the kind of feeling that I had when I first heard Sinking of the Titanic, which was a volcanic experience for me, just huge, I'm satisfied. I thought, you know, these things give me a place to create something unique, as opposed to rock and roll, where I spent a lot of years because I was having fun.

What can I say? Yeah, I had a band with Don Fleming that I thought was the greatest band in the world. When I played with the Butthole Surfers, I thought I was in the greatest band in the world. Ween too. Same feeling. Even Bongwater was the greatest band in the world, briefly. I don't know what I was thinking.

Grella: Well, you weren't wrong.

Kramer: Well, I was wrong, but I was having fun, and I was also helping an awful lot of people to make records, and that made me feel really good. And I was into feeling good as much as possible at that part of my life.

Grella: When I was a musician playing CBGB and the Knitting Factory, we were all like, "What's Kramer doing on Shimmy-Disc?" Because there was a community of music around you, which was an essential part of the whole Downtown scene.

Kramer: I probably would have achieved none of that without Noise New York. And I bought that studio in 1985 because I thought I was going to die on the road with the Butthole Surfers. This was when they were still driving around in a van with razor wire wrapped around the front. And when I joined the band, they all took the opportunity to do even more drugs, because they now have someone in the band who only smokes pot. And you can drive when you're smoking pot, pretty much, so I was the designated driver, and I just thought, this is untenable. I wanted to be in the studio.

Grella: Talking about the new record, you said that you're a performer, not a composer. But the way you described making music, that's composition.

Kramer: I'm a spontaneous composer. Let me put it that way. I don't write anything down on paper; I simply sit down and begin. It's like breathing, it just happens.

Grella: As a musician making your own music, and especially as a record producer, the recording studio is notation paper for the 20th and 21st centuries. We have this idea that it's locked into writing things down on staff paper, but it's really just taking musical material and working it and reshaping it.

Kramer: Exactly, and the recording studio also makes it possible for people like Eno, who are terrible musicians, to make some of the greatest music in the world. A mixing console is a musical instrument that helps people who don't have musical talent to articulate ideas that may be great. Like great, great ideas. I don't know if Aphex Twin can play an instrument, but he sure does make some of the greatest music I've ever heard.

Grella: There's a difference between being able to play an instrument and being musical. And you're deeply musical because you think in musical terms, and you can form musical ideas. It's just that you use a different way of doing it where the culture at large would say, "That's not musicianship," but it absolutely is.

Kramer: As a kid, I was always the second-best organist in New York State. My parents always had me in the organ competitions, even before my feet could reach the pedals. So I would always get top grades with my right and left hand and zero on the pedals, because I had to do it standing up. So, yeah, I'm a musician, but I'm much more interested in the things that people who don't have that kind of talent are able to make; those are the things that attract me. Accidental things, I can catch in a bottle and preserve, they might be erased if I wasn't there. That's the most important job in the studio.

My current work, it's a genre-less effort, really. I'm not trying to do anything in particular. I'm not setting myself on a path with a destination, and I want the listener to know that. I do call it ambient music, because I have a record label, and if you want to sell something, people want you to tell them what it is. We're not talking about the '90s, when there were music journalists around. You're a dying breed. You listen to music, think about it, and then write about it. Most of the people I know who did that 20 years ago aren't doing it anymore because they have a little bit of self-respect. They used to get paid to do it, and when the money stopped, they said, "I'm not doing this for free." I'm dealing with magazines that don't listen to anything. They just read PR releases, and then they cut and paste.

Grella: What's so intriguing about the new album is that, yes, call it ambient music, but it's the thing where you listen, and you find yourself captured by it; it's producing responses in you that you can't really put a name on. That's the key thing that active listeners are always looking for.

Kramer: It's like Pauline Oliveros' use of reverb, and my use of reverb, and a lot of the great Low and Galaxie 500 recordings, there's something about reverb, you know, it almost makes the present disappear. It's like a reminiscence of the future. You have this sound that you've made, add reverb to it, and the sound somehow magically continues, and it dies away slowly if at all, maybe it morphs into some other kind of sound. I always thought there was a reason that madrigals in centuries past weren't sung out on hilltops. They were sung in churches where the sound would reverberate and do something magical to the nervous system. People would be in a state of ecstatic grace, listening to this music that changed very slowly. It wasn't just about devotion to God. It was something happening in your brain when you hear music that evolves ever so slowly and changes imperceptibly. Music is usually something that comes toward you. Maybe I'm trying to create something that makes you come to the music. I feel like I'm in another world, and that's what I hope the listener will feel.

If you're attending Big Ears 2026, be sure to catch Kramer performing solo and with Pan American.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSteven Garnett

The TonearmSteven Garnett

The TonearmGeorge Grella

The TonearmGeorge Grella

Comments