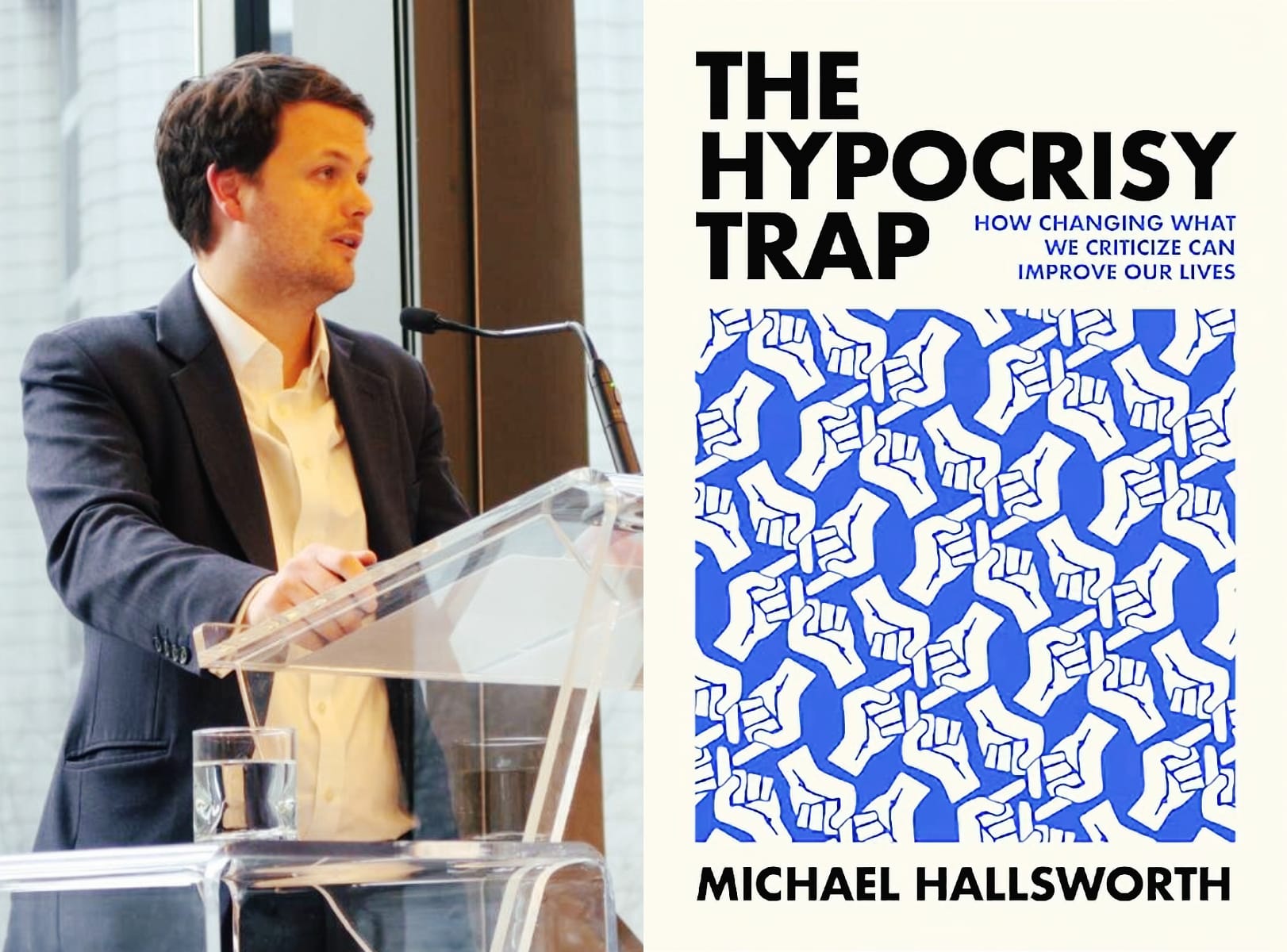

The Behavioral Insights Team was established by the UK Prime Minister in 2010 as the first government institution dedicated to applying behavioral science to policy questions. Michael Hallsworth joined as an early member and now serves as managing director for the Americas. Over eighteen years, he has worked as both a government official and advisor, applying empirical research about human behavior to social purpose goals. His work has appeared in The Lancet, the Journal of Public Economics, and Nature Human Behaviour. He holds a PhD in behavioral economics from Imperial College London, has taught at Columbia University and Princeton University, and serves on the editorial board of the journal Behavioral Public Policy.

Hallsworth's recent book, The Hypocrisy Trap: How Changing What We Criticize Can Improve Our Lives, applies behavioral science to a problem that has intensified in our current political and social climate. The premise is straightforward: accusations of hypocrisy are everywhere, but our attempts to stamp out inconsistency often backfire. The book argues that not all hypocrisy is equal, and that our reflexive condemnation of any gap between words and actions has created what one reviewer calls "a sharp, clear-eyed case for backing off the moral outrage."

The inquiry began with a basic observation. "It was only about fifteen years ago that actually anyone started to ask people what they thought it was," Hallsworth notes about hypocrisy research. The concept originated with Greek theater and was later weaponized by religious authorities, but systematic study of how people actually understand and deploy accusations of hypocrisy is surprisingly recent. This research challenges comfortable assumptions: hypocrisy operates less as a moral category than as a social tool, used to claim status, damage opponents, and enforce group boundaries. Behavioral science shows that exposing hypocrisy, particularly that of authority figures, has long-lasting effects precisely because it undermines trust.

Michael Hallworth was a recent guest on The Tonearm Podcast. Joining host Lawrence Peryer, he discussed how behavioral science illuminates the mechanisms behind accusations of hypocrisy and how societies can preserve meaningful standards without descending into either purity regimes or cynical power plays. Hallsworth also explained why reconsidering our relationship to hypocrisy matters for democratic institutions, organizational trust, and personal relationships.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the audio player below. The transcript has been edited for clarity, length, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: What is behavioral science primarily concerned with? Where might we see behavioral science in action?

Michael Hallsworth: Behavioral science is the structured study of how people behave in real-life situations. We might look at whether a particular message makes you more or less likely to turn up to your doctor's appointment on time. We might look at how the design of a hospital ER encourages people to wait without getting angry or annoyed. How does the design of the physical environment actually ensure you know where to go and that you get a sense you will be seen without waiting too long?

It's about these different factors in the environment, the kinds of messages or inputs we get, and how we react to them. The core insight is that, sometimes, we pay attention to all the information. We weigh up the costs and benefits of acting and choose the best course of action. But quite often, we are using a set of mental shortcuts to navigate the world. What behavioral science tries to do is say that you need to take those mental shortcuts into account when you are designing your hospital and formulating your message. That's what we try to do. We try to help people take those ideas into account to get a realistic sense of why people behave as they do.

Lawrence: Before we jump more specifically into your book, The Hypocrisy Trap, can you tell me a little bit about the work you've been doing thus far in your career? How did your work experience come to shape your understandings around human inconsistency?

Michael: The work I do is focused on social benefits. Rather than the private sector, we've tended to look at issues that affect society as a whole. Quick examples: we did work in San Francisco to say, how do you redesign intersections to minimize dangerous left turns where people are turning into pedestrians crossing? You might also be attempting to influence people in certain ways. I mentioned social norms, but one great example was that we did some work on antibiotics, telling doctors they were outliers in their prescribing. They were prescribing antibiotics much more than people like them in their local area. It turned out that those outliers reduced their antibiotic overprescribing after they found out they were outliers. The information had never been there for them or presented in that way.

There are actually quite a few things from behavioral science that help us be more consistent. I can show these examples from commitment devices, increasing the costs to yourself of not meeting your goals, or things like this idea of induced hypocrisy, where you basically point out to someone gently in private all the ways that they haven't lived up to their public pronouncements, and they go, "Oh wow, I should think about that." It can lead to changes in behavior.

Lawrence: You noted the difference in behavior you get from the subject when you address their hypocrisy privately versus when you publicly shame or name them, which often induces almost a defiant response. I'm curious, what is that mechanism all about?

Michael: The unfortunate situation is that we like calling out hypocrites in public. One reason for that is that it makes us look good ourselves. There's a status thing going on here, and I explain that I think a core driver of the whole hypocrisy trap is the desire for status and the desire to get status by taking down other people who you think are hypocritical.

The problem is that if you do that, we humans have loads of really good defense mechanisms for denying the reality that we've been inconsistent. We try to say it wasn't really an inconsistency for all these reasons. We try to redefine what we've done. We say that maybe I didn't really care about that after all. We go on the attack and say, "But you are inconsistent as well," because we fear losing that kind of status and face you get from a claim to consistency with principles.

Instead, if you talk to people in private, you give them an off-ramp or more of an off-ramp. You don't get that defensiveness so much. You give them the space to think, "Oh, actually, I wasn't very consistent with my public statements here, and what can I do differently?" You get away from that reactance of maybe, "I don't care about it after all," to a space of, "What can I do to actually change to get there in the future?" It's very much bound up with our self-identity and status, and doing it in private removes much of the stakes there.

I can give you some examples. If you talk to people about those who have made public statements saying you shouldn't use your phone while driving, that's more likely to have an impact if you tell people in private and then use technology to point out the inconsistency. It's actually harder when someone is sitting across the table, judging you.

There's another experiment I talk about in France where they asked people to sign a pledge not to use plastic bags in supermarkets. If people did that, they were less likely to use plastic bags. But if they were also asked to think of all the times when they had taken a plastic bag in public, they actually became more likely to take a plastic bag because they thought, "Well, maybe I use them, and maybe I don't really care about this issue."

Lawrence: When talking about calling out hypocrisy as status, there's also this idea of false signals as opposed to just morality at stake. What's the distinction there you are getting at?

Michael: The first thing to say is that we think that hypocrisy is about morality, often about virtue, but it doesn't have to be. The experiments show this. You can be a hypocrite if you are actually concealing your virtues as well. Say you've got an image of yourself as a maverick or rule-breaker. Take a teenager who wants to look like they don't care about authority with their friends, and yet they go home and diligently do their homework. So your status can come through various kinds of claims.

The point then is that a lot of the time, what we don't like is the false signals of consistency that people send about whatever principle or status claim they are making. This is the reason we really don't like hypocrites. Maybe take an example of someone talking about downloading music illegally; this is just one study that was actually done. Two friends are talking about downloading music illegally, and in this experiment, participants saw one of three endings. In one ending, after condemning it, they're told that this person downloads music illegally. In the second ending, they say it's morally wrong to do it, and then they go and do it. In the third ending, they say it's morally wrong, but sometimes I do it anyway, and then they go download music illegally.

The reason they do this experiment is that in the first case, the person gives no judgment or opinion about downloading music illegally. In the second one, they condemn others for doing it. In the third one, they say it's wrong, but that they sometimes do it. It turns out that people obviously judge the second person much more harshly, but the third person is judged no worse than the person who says nothing. The reason is that they've removed this kind of false signal. They've admitted that they may sometimes do it, so they're not claiming to be this signal of consistency.

In case you are wondering about lying and the difference between lying and hypocrisy, not all lies are hypocritical. For example, if I ask, "Did you steal that newspaper?" And you say no, assuming you did, that's a lie, but it's not hypocritical. Whereas if you responded by saying, no, I would never steal a newspaper. People who steal newspapers are wrong, and we should crack down on those people really harshly. You can see it becoming more hypocritical because you start sending a stronger signal that you are not the kind of person who would ever steal a newspaper. That's where the hypocrisy comes in. That's why it's about signals.

Lawrence: It's really the central issue you are sort of wrangling with in the book—this idea of we can't all walk around as scolds and persecuting people any more than we can simply abide by any kind of unguided, unprincipled behavior. I'm curious, could you talk a little bit about the counterproductive repercussions of this constant identifying and going after the hypocrite?

Michael: The book's called The Hypocrisy Trap. When I say that to people, I think the instant reaction is, "Oh, the trap is being hypocritical."

Lawrence: And you've been caught. (laughter)

Michael: Yes, you've trapped me. That's actually not the main thing I mean. As I mentioned earlier, the book does talk about how to be more consistent with our goals, and we use various behavioral science approaches to do that. But actually, the trap is more about what happens when criticisms of hypocrisy get out of control.

Some calling out of hypocrisy is healthy. It protects shared standards, and it preserves trust. In the book, I call this the 'trust machine.' When it's working well, we call out hypocrisy and politicians; for example, they know there's an incentive to tell the truth because if they don't, they'll get called out for being hypocrites, whatever.

At the same time, we know from our own lives that letting go of inconsistency and hypocrisy is necessary and healthy because life involves trade-offs, imperfection, and imperfect steps forward. There's something cold, hard, and inhuman about the drive to eliminate all kinds of hypocrisy. So I talk about another scenario called 'everyday compromises,' which kind of works pretty well. We don't have complete consistency. We decided to make certain trade-offs. People are quite forgiving of each other.

And yet here come the bad things. For a start, if you take the criticisms too far and you say that every kind of inconsistency is punished, you end up with something I call the 'purity regime.' People feel like they can't even voice any principles because they're worried about someone calling out some minor inconsistency, or they have to pretend like they are following everything exactly. There's a good historical analogy here in the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, which Hannah Arendt called a relentless "hunt for hypocrites." So that's when your criticisms go too far.

But then there's a final thing that can happen where you basically end up in a world where no one cares about hypocrisy, where you don't criticize it at all, perhaps because the concept has become exhausted. We have so many accusations that everything is hypocrisy, so nothing is. So what are you going to do about it? I'm a hypocrite. The difference is I'm stronger than you, so I can just do what I want. Are you going to stop me? So what if I'm a hypocrite? I call that world 'brazen power plays,' and that's really a bad world as well, but it's the opposite of the purity regime.

You want to end up in those two good worlds of the 'trust machine' and 'everyday compromises' and avoid the two bad worlds of the 'purity regime' and 'brazen power plays.' You do that by not overusing the accusations of hypocrisy. That can lead to a world where either hypocrisy is everything or it's nothing, and both are very bad places.

Lawrence: Are there any historical examples where the community evolved beyond it? How is stability regained, reestablished, or is it not?

Michael: The way I think about it is that we have to resist the temptation to call out even the slightest inconsistencies as hypocrisy because sometimes, particularly in politics, your accuser has an agenda. Quite often, the accuser wants to look good themselves, and hypocrisy is a really good way of damaging another person. Again, I'm not excusing hypocrisy all the time. I want to make that really clear. I'm not condoning deception, lying, or malign intent. I think there's a ratcheting effect of accusations that we've been seeing, maybe also because of social media, because social media gives you a vastly increased number of traces of someone's behavior and statements, and also gives you a vastly increased number of platforms to make accusations. The two things are kind of related: the accusation and the perceived hypocrisy.

Your question is actually a really good one in terms of how you emerge from the other side. One way to answer is that the 'purity regime' setup is inherently unstable. The Reign of Terror reached a pitch at the end when Robespierre himself was executed. Then everyone just calmed down a bit because they realized you couldn't be completely consistent. It wasn't so much about ideological purity.

Then I think the 'brazen power plays' are just an unproductive world, like a state of nature. Everybody's scrambling for an advantage. It can lead to complete chaos and breakdown because there are no governing institutions or rules. It's just a struggle to get as much as you can with force. But there are advantages to cooperation. I think that's how you get out of it. But I'll tell you, that's the first time anyone's asked me that question. It's a really good one. I hadn't thought about it. How do you exit those bad worlds? They're really hard to exit sometimes because they get locked in.

Lawrence: I really love your identification of that notion of purity as being such a big part of the problem because it's a toxic notion across so many domains. It doesn't leave room for mistakes, compromise, or grace. It winds up excluding so many people who might score eight out of ten on a scorecard—they just don't get to participate anymore. And it treats all infractions equally. There's no difference between a mortal and a minor infraction.

Michael: That's really true, but you also have to be careful with the other side of it. If you become too accustomed to giving yourself a break and sort of saying, "I'm basically a good person; I just failed this time," then you actually open the door to complacency and even cruelty in the end, because you could start ignoring the consequences of your actions. Strategically, I talk about the zealot's view of the world, where it's like you have to be completely consistent, and they would say every evil ignored is an evil you tolerate, and they kind of have a point there. This is why it's so slippery. You can't just say, "Oh, purity is bad," because compromise can be bad as well if it's taken too far.

Lawrence: I feel like this is the central tension of our time, but maybe it's been the central tension of all time. I'm going to do an annoying thing and ask you for some prescription or guidance. Someone reads your book, and it gets them to reflect on their own hypocrisies. How do you counsel them to navigate that gap while still balancing their principles, living a practical life amongst other people?

Michael: I'm going to try to sum this up quickly. One is that there are techniques to become less of a hypocrite, and I mentioned some of them. The second one is anticipating how people will judge your actions. I try to lay out very clearly what really annoys people and ratchets up the sense of hypocrisy. We actually know this from studies, so there's almost a protective thing you can do yourself to try and reduce the risk of being called out as a hypocrite.

But then the final thing is changing the view of hypocrisy, and I have some simple things here. When we see an accusation of hypocrisy, try to think about the real harm involved. You'll see a lot of accusations of some kind of inconsistency, labeled as hypocrisy, because people know it will rile people up. So, think about the person's motivation in making this accusation of hypocrisy, and how substantive the thing going on here is. Because it's often used for very minor things. You should be thinking, "Is hypocrisy the real issue here, or is there something else underneath it? What's the real issue that's getting people annoyed? Do we need to be having this conversation about hypocrisy?"

Hypocrisy is often just laid out to make us angry and get our attention, because it's really good at that. It's the thing a politician can use against their opponent to cause the most damage in a short space of time. So what's going on? Don't just think about the hypocrisy, think about the accusation, because that's part of the whole system as well.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments