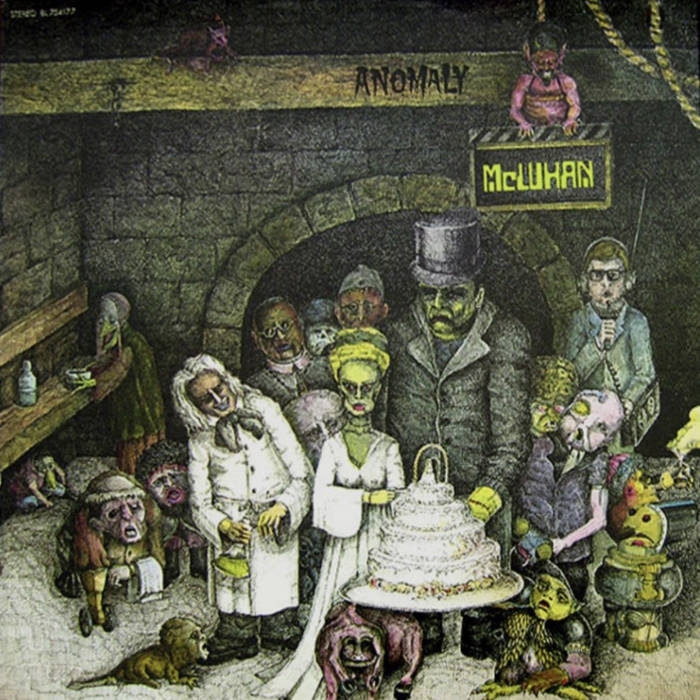

One of the strangest albums of the early 1970s is also one of the unlikeliest. Released on Brunswick Records in 1972, McLuhan's Anomaly is an album full of bizarre musical twists and turns, a sonic excursion that takes the listener on a trip through many styles of music—styles that by all rights don't belong on the same record. But in the hands of a group named after a famous philosopher and media theoretician, somehow it all works.

The four lengthy pieces on Anomaly travel through myriad musical textures. There's vocal pop reminiscent of the Association. There's powerful fusion along the lines of King Crimson or Centipede. There's progressive rock with horns, the likes of which would impress fans of Frank Zappa. There's wild, atonal free jazz à la Albert Ayler. There are snatches of melodies from film and theater. And there are spoken-word passages suggesting an unholy meeting of the Fugs and Firesign Theatre. Sometimes these disparate pieces are crammed into a single song. It's wicked, wickedly funny, and weird. True to its name, Anomaly is like nothing else.

Calling their band McLuhan, the Chicago musicians who made Anomaly held on just long enough to make their sole record, then broke up, leaving behind a fascinating minor masterpiece. Yet few listeners knew of Anomaly's existence, much less heard the music on the record.

But the story wouldn't end there. Decades later, in the Internet era, buzz about this rare and strange album began to circulate. Sensing an opportunity, a label in Europe repressed Anomaly without the group's knowledge or consent. That led to more discussion of the album and its unique charms. Then something even more unlikely happened: most of the original group got back together, playing the music they had recorded in the early seventies. Eventually, the group arranged a limited-run vinyl reissue of the album, and in 2025, Think Like a Key Music licensed Anomaly for its first-ever CD release.

Today, McLuhan include original members Neal Rosner (bass) and Paul Cohn (clarinet, flute, saxophone, and woodwinds) and Tom Tojza (keyboardist on Anomaly). At shows, the band perform Anomaly in its entirety along with new music composed by Rosner in a style that complements the music from the band's all-too-brief early seventies incarnation. Paul Cohn spoke with me about the improbable saga of McLuhan.

Bill Kopp: How did you end up in a group like McLuhan, making this strange music?

Paul Cohn: I started playing clarinet when I was eight years old. My dad bought me a clarinet and got me lessons from a guy down the street named Bob Gordon; he taught me how to read music. I went from there to a Polish wedding band that somebody got me into, and then when I was about twelve or thirteen, I joined a bar mitzvah band called the Sophisticates. Neal, my next-door neighbor, was trained in music and had a tremendous gift. He knocked on our door after we started developing, and he said, "Maybe I can help." We told him, "We need a bass player," so he learned the bass.

A few years later, Neal and I were playing and performing together in this other band called the Seven Seas, doing Burt Bacharach, a lot of that kind of thing. We had a female singer, and the group was rehearsing in my basement at one point.

Dave Wright was a trumpet player; we were both in the band at the University of Illinois at Chicago. I brought him into the group. But there were some disputes going on in that little band. And when the group broke up, Dave said, "I have this idea, if you guys want to work on it." And so we launched this McLuhan thing. We were developing it in rehearsal and then performing it at fraternity parties, college events, and that type of thing.

There was a guitar player at that time named Mark Rabin. He was someone I knew from the South Side of Chicago; I grew up at 100th and Calhoun. He lived the next street over at 100th and Hoxie. I ran into him on campus and he said, "I play guitar." So he joined. But he was breaking his guitar at every performance, emulating Pete Townshend.

And then we got this job, Monday nights at the Wise Fools Pub.

Bill: How did audiences react to McLuhan's music?

Paul: I have memories, especially of Wise Fools Pub. We developed a following there pretty quickly. One of the songs on Anomaly is "Witches Theme and Dance." It's a sarcastic thing that Dave had; it's about the McCarthy era, witch hunts, all things that kind of parallel today. I remember playing that piece, and at the end we speak/sing the lyrics: "If you understand this song, then you might just sing along. And for those who cannot hear us..." I distinctly remember being lit up because of the enthusiasm of the crowd. It was going over very well in that scene.

But we were never promoted. Maybe we would have caught on if we had been promoted, but we did a bad job connecting with promoters. Coming out of Wise Fools Pub could have helped launch us, but we didn't have time on our side.

Bill: How did the band wind up on Brunswick Records?

Paul: There are a few different theories about why Carl Davis of Brunswick came to our performance at Wise Fools Pub and then invited us to do the album. But the one that I think is accurate is this: at that time, my mother was working for some attorneys. One of those people knew someone at Brunswick; maybe they were doing work for them.

Brunswick was mostly soul music: the Chi-Lites, Tyrone Davis, that type of thing. So we didn't fit in there. But they came to the performance and apparently liked us. Bruce Swedien was looking for something a little more expansionary, and so they pushed it through. We got a phone call. Maybe a week later, I was walking down Michigan Avenue to Brunswick Studios.

Bill: How much of the work was composed and arranged before entering the studio?

Paul: Before we started working on the original McLuhan material, we were covering Chicago: "Beginnings," "Make Me Smile," some of that stuff. And then we started evolving this "anything goes" idea that Dave had. We were four or five months in preparation, taking Dave's music, developing it, and then probably another six months of performing it. I think we had one or two gigs at the University of Illinois, where most of us were going to school, and we played a few fraternity parties. Then we got the Monday night gig at Wise Fools Pub; that went on for about six weeks. We were only in the studio for three days and then done.

Bill: The music on Anomaly is wildly eclectic, heading in very different directions several times—even within a single song. Where did that music come from?

Paul: Dave Wright composed most of it, although we developed a lot of it in rehearsal. But he came in with Marshall McLuhan's idea that "the medium is the message," and that idea allowed us to do virtually anything in the studio. There were some limits because we were doing different styles, but we were combining them in ways that we thought were valid because of the theory behind it all. We weren't looking to create something commercial. There's nothing commercial about Anomaly. And we knew it, too.

"A Brief Message from Your Local Media" is the story of McLuhan: there were the stages of man, when man was all together and interacting. And then print came along; it separated everybody. Then there was the assembly line, then radio, then television. And the thing that propels us now is the media; today it's that and the Internet.

Bill: At the time, did you realize that you had created something special in Anomaly?

Paul: I remember Dave calling me up afterward. He asked, "Paul, what did you think?" And I said, "Dave, I don't know if it'll ever go anywhere, but we really put something together. We really launched something."

It was a very quick transition from bar mitzvah music over to fraternities and then to Monday nights at Wise Fools Pub and then the studio. It all happened within no more than fourteen months or so.

Bill: Did you know when you entered the studio that the band was already at its end?

Paul: I was so overwhelmed with the opportunity to go down to 1400 Michigan Avenue and climb those stairs into that studio that it might have been in my head that, "I'm not sure if we're going to be able to stay together." But we didn't know what we could do next to keep the group together. We saw the studio session as an opportunity to put down what we had developed.

Bill: How long did the band hold together after the album was completed?

Paul: I don't believe there were any performances. Not until fifty years later.

Bill: When did McLuhan start performing again?

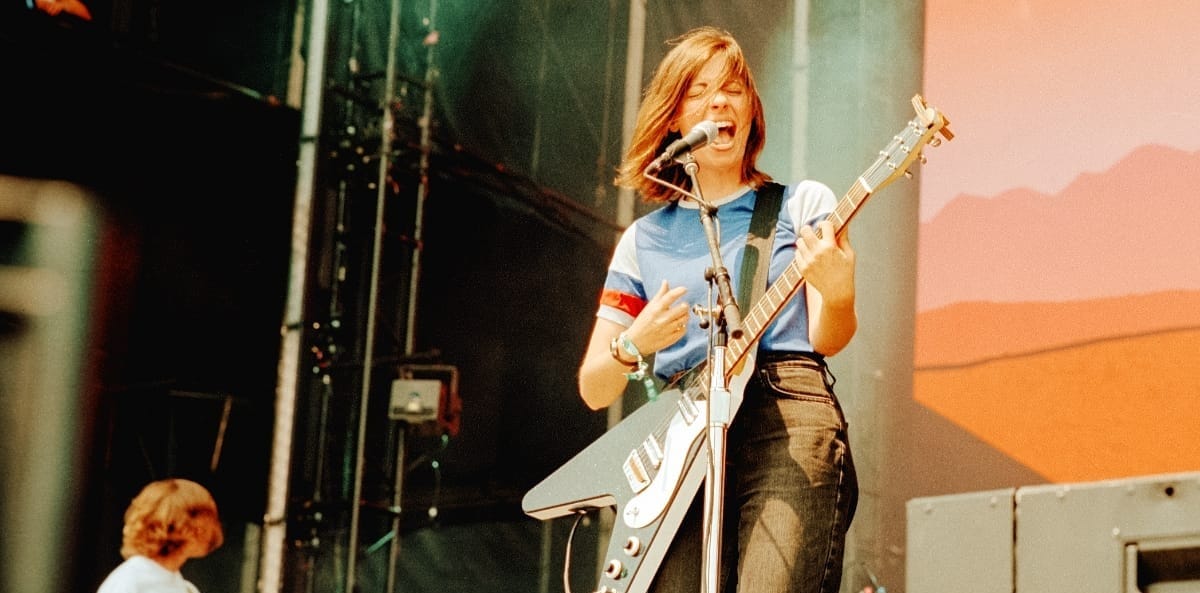

Paul: We started around 2019 or 2020. During the pandemic, we played a couple of times where the guys who didn't have to play horns would wear masks; we dealt with that. But we've been back talking together, rehearsing a little bit, and playing for about five or six years now. Between the eight or ten establishments that have booked us, we've done about thirty-five to forty-five shows in Chicago.

Bill: I recently watched on YouTube a McLuhan performance from the Hideout, from the Chicago Psych Fest X in 2019. You played the whole album start to finish. I went into it thinking, "Well, this will be interesting, but I can't imagine that it's going to sound anything like the album." But it really does.

Paul: Yeah. Now, with the three or four of us still together, I've been able to get transcriptions done. So what we do now is a live performance that's closer to the album than what we did back then.

Bill: When you look back at McLuhan and Anomaly, what are the thoughts that stay with you?

Paul: We shared and developed ideas regarding the medium being the important thing. There were no limits as far as musical styles, and for a short time, we were able to develop that for live performance. It was a moment in time that got us to the studio. And then we all went our separate ways; I went into business, and for many years, though I kept my horns going on the side.

But when I look back on my life—I just turned seventy-five—I don't care that we never made a dime off of it. What we were leaving behind was really significant in terms of the thought process that went into it. In my life, the one artistic thing I'll be leaving behind is this album. It's been heartfelt beauty given to me.

The way it happened in the studio was miraculous, putting us together with an amazing engineer. And it was a great experience. When we left, we knew we were all going different ways, but we had left Anomaly behind.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmBrook Ellingwood

The TonearmBrook Ellingwood

The TonearmChaim O’Brien-Blumenthal

The TonearmChaim O’Brien-Blumenthal

Comments