Yesterday, February 6, from the safety of my couch, I saw a video of 2,000 protesters singing outside ICE Headquarters in Minneapolis. I live an easy commute away from Minneapolis and St. Paul, in a small college town where I teach music. Music's part in Minnesota's crosshairs moment has been consistent since the murders began—drummers assembled along the stone arch bridge, then on street corners a few weeks later. Marchers vocalizing contrafacta about Kristi Noem that didn't shy away from the worst words. A friend even invited me to play drums at his studio so he could then blast the recordings at the storm troopers; I went up and did so after running around on campus, dorm to dorm, to see if the ICE agents spotted in town had invaded the college. Given that, it was easy to find the energy to drum. If loudness and polyrhythms can fix all of this, you're welcome.

This particular video is distinctly different from the more assertive efforts I just described. The framing of this performance and its viral transmissions has been, understandably and accurately, that it is fundamentally based on nonviolence, committed to positioning oneself above hatred, above an equal-and-opposite meeting of force with force. You go so low, we still go so high. If this is the face of 'domestic terrorism,' we rational beings concur, maybe we need to distinguish the vocabulary used to describe someone who blows up a federal building from people singing nicely on the street outside a fucking hotel.

"It's OK to change your mind," they sing out. For those who have not been to a Minnesota restaurant when someone else is having a birthday, people here come from a long line of vocal-performance capacities that are fairly staggering, if shockingly casual when publicly deployed. The feeling is "oh, this old thing?" as the harmonies stack.

More on that soon. But first, I meant to write an essay about "A Case of You" by Joni Mitchell, before the federal government invaded the state. It turns out these are related phenomena. I was recommended to listen to a November episode of The Secret Life of Songs that takes up the very same song. I love that this aired in November 2025, that I listened today, and that the contextual work at the beginning of the episode was to say that at this time, in this county, in that Los Angeles neighborhood, we could plausibly argue that singer-songwriters had all but betrayed the promise of making music that makes or is at least concerned with justice, that transforms the world or, at the very least, tries. The argument in rock criticism at the time was that James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, and Graham Nash—and their set—went from changing the world—impossible—to changing themselves—hard—to let's just make some money.

Besides the binary opposition this contextual work establishes—between music that is concerned with others vs. music that is concerned with the musician herself—this setup reminded me that most of how we think and talk and write about music tries to say what it is or what it is like. My orientation is typically neither of those, though they are certainly helpful in many encounters. In the classroom, for example, one can't really get around what this or that piece "reminds me of," sounds like, or, if it's known to be a kind of island or solar flare, what it actually maybe is. ("The first time a Moog played a kick pulse!" "A prototypical New Complexity score." "A ripping solo over 'Giant Steps' changes.")

I find another orientation useful, more interesting, and more accurate: What does this music do? In "A Case of You," I am struck not by the interiority of the concern or the depth of expression made possible by truly maniacal vocal zigzaggery, though those are certainly there and certainly hard to miss. Instead, I have an equally spellbinding and disquieting sense that Joni Mitchell is riffing on an archetypal melody, and that I cannot actually figure out what it is, cannot reconstruct it. The weird ends of phrases that are clearly anticipations, syncopations, delays? Surely they are making those time-blurs in reference to some stable rhetorical thing, but what? The melodic jump-overs, runs, twists, and turns? There is a stock version of where to land in every moment that she chooses not to indulge, but again, I can't really figure out what those safer landings are or where they ought to be.

Enter an on-the-nose explanation that actually, to me, makes emotional, experiential sense: We plumb the infinite vectors of any relationship, smattered across time. We pull at those various strings or look for a coherent story we might tell ourselves. But in the end, the center we seek does not—perhaps cannot—hold. If there is any center, it is just the negative space around which all those swirling impulses orient. For the Star Wars people (hi friends!): How did the Padawan learners find Obi-Wan's lost system? They looked for evidence of gravity. If everything is bending in relation to something, then there must be something there, whether or not we can see it with our eyes (or hear it with our ears). It's cool to be able to do that, just like it's cool to find yourself in the Hollywood Hills. Too bad about the world on fire.

Except, to bring this back to the top: It's OK to change your mind. If you do, it turns out the world around you changes. It sounds incredibly stupid and naive, but it has the virtue of being, in my experience, observably true. The Pali word dukkha might be useful here, as well as its typical (mis)translation: Suffering. "Life is dukkha," as the Dhammapada begins, appears to bear out in the first weeks of 2026, as masked gunmen yank people out of their running cars, or shoot them in their cars, or shoot them multiple times while they're lying on the ground.

Unexpectedly, given the quotidian understanding (to the extent people are running around with any translation of dukkha in their heads), dukkha actually concerns itself with small-s suffering. I learned recently that it describes, specifically and idiosyncratically, an axle that doesn't fit its wheel as well as it might. The cart is still moving, but it's really annoying that something seems, now and again, to be sliding around. Dukkha describes pebble-in-shoe suffering vs. stepping-on-a-land-mine suffering. These are very different affectively and at the level of pain scale, yet they are bound to each other. Connected. In shocking fact, the one causes the other; get the rock out of your own shoe, and it turns out you'll be deeply disinclined to blow someone else's foot off. Not a news flash to say that harm begets harming. But for me, it is actually useful and different to say that the billion ways that half of America seems to be diverging from the other half of America are built on the way all of us are perpetually scratching an itch that will never go away. In fact, we are often engaged in the process of building our lives around how we might most effectively, or righteously, or justifiably scratch our own itches at some other itchy person's expense.

Put that way, the 1970s Laurel Canyon singer-songwriters' inward preoccupations might be re-framed. If you can change your mind, you might say to someone, with words or with a song, something like, "I know the world is this way." For me, for you, for everybody. Here is my subjective account of that, in all its complexity, in all its sensation and tangled history laid bare. The way I say it itself says how it might be different. A new world comes along for the ride.

We are all trying to say to each other how this world seems to be. At the height of any form, the way in which that is articulated is itself, also and already, a tacit imagination of what the world might be instead. In other words: It's OK to change your mind. I could drink a case of you. Like holy wine.

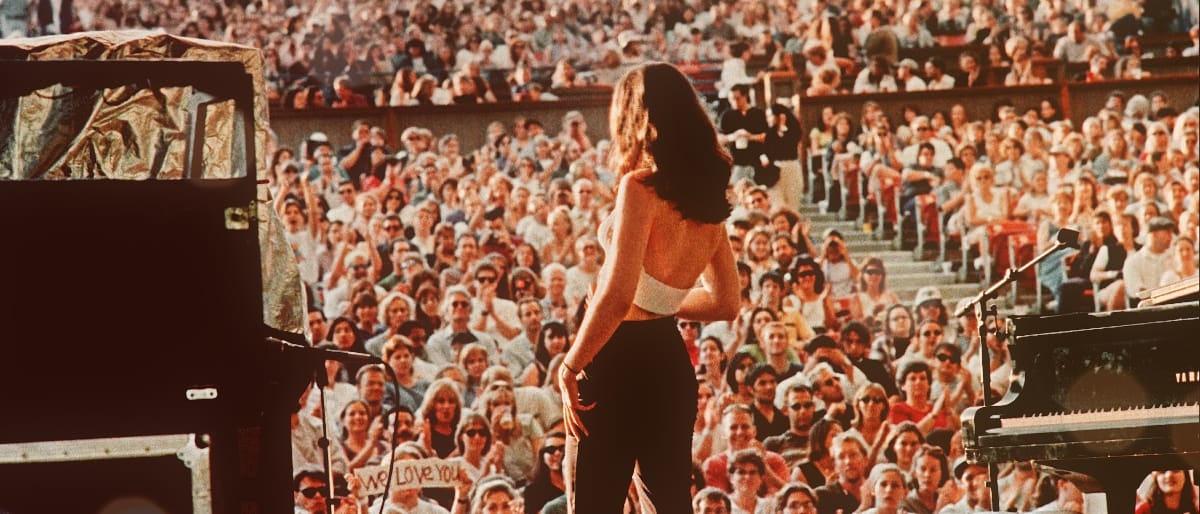

Joni Mitchell's middle-school English teacher told her to write in her own blood because that is the only way the work might be legible to others, at which point they might realize that they are at yet another choice point, that they might walk out of that hotel and take off their masks. And, for those of us singing in the streets, that the fulcrum on which this moment turns is not the miraculous transformation of an enfranchised and malignant narcissism, but rather our collective capacity to honestly say how things are and to hear in that unencumbered, highly subjective telling, the way they might be. Music is like that, and music is that. But music also does something. In Joni Mitchell's case: circles the drain of whatever achievement of miraculous and complicated love bound these two humans to each other in their time together and across their estrangement. In the case of the good and heroic people of Minneapolis: it reveals another choice point, illuminates a fork in a road made of only forks. And just like Joni Mitchell, even after drinking all of that down and writing it in blood: We will still be on our feet. Yes, there is a difference between marching and dancing. And yes: in the still frame before the music starts, it is impossible to tell them apart.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmAnthony David Vernon

The TonearmAnthony David Vernon

Comments