Ahoy, newsletter fans! Excuse me as I calmly sidle next to you on this lazy Sunday and present this week's edition of the Talk Of The Toneram dispatch. This one is jam-packed (so many links—you're welcome/I'm sorry) and features plenty of unexpected detours derived from a rousing quartet of our recent articles. I'm excited for you to dig in, so I'll end my intro now and invite you to veer inward:

Surface Noise

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

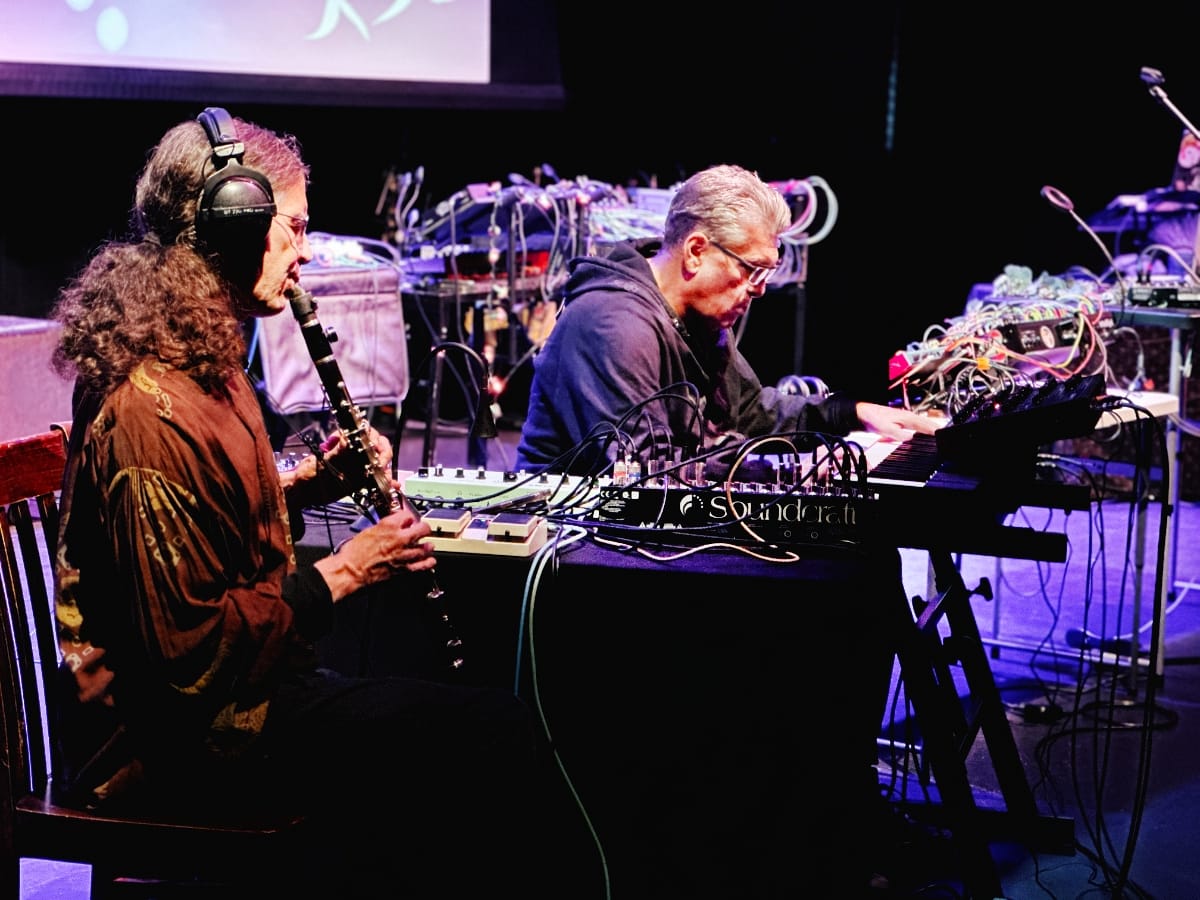

Bob Familiar reads a lot of science fiction, the storylines seeping intentionally into his electronic music. He once even undertook the challenge of translating the vast temporal scales of Cixin Liu's The Three-Body Problem into sound. Of course, electronic music, as a sonic guidepost of new technology, has always accompanied sci-fi, from Louis and Bebe Barron's use of ring modulators in The Forbidden Planet to Delia Derbyshire's classic work at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. And synthesized sound-making often tackles the same questions about time, consciousness, and non-human experience that drive the best speculative literature. Familiar's collaboration with clarinetist Glenn Dickson on All the Light of Our Sphere sits upon this philosophical mantle, filled with unsynchronized loops that independently shift in structure while Dickson improvises melodic narratives.

Things can get heady and dizzying when speculative fiction contemplates the infinite (see The Three-Body Problem, above). But sci-fi-inclined electronic musicians can simulate thinking in geological time or through non-human consciousness in an accessible way, using repetition, generative transformation, and non-linear development. Familiar uses synthesizers and digital processors to explore Kazuo Ishiguro's questions about authentic emotion in artificial beings, synthetically imitating human expression. His Expressive E Osmose keyboard responds to subtle variations in touch, allowing physical gesture to control brightness and texture—a sonic parallel to Klara's struggle for connection despite her artificial nature.

When Familar and Dickson perform, no single rhythm dominates, and sounds interact according to chance and careful listening rather than predetermined hierarchy. If we want, we can think of this technique in terms of speculative fiction's challenge to anthropocentric thinking. Even without cutting-edge technology, chance operations remark upon consciousness, artificial intelligence, and non-human forms of experience. There aren't answers to these questions, but these types of performances invite listeners to witness the asking. In other contexts, this sort of pondering would mostly be academic, theoretical, and, well, boring.

Playback: Shifting Realities — Julius Smack's Starlight as a Dystopian Reverie → Julius Smack also ponders artificial consciousness and speculative futures through synthetic sound, positioning his alter ego as an alien from the future who explores themes of identity and technology. His excellent album Starlight presents a dystopian narrative where AI has decimated civilization and artists survive using technology to process and express human experience.

The TonearmGarrett Schumann

The TonearmGarrett Schumann

Michigan music scene veteran Fred Thomas borrowed a friend's tape machine with ambitious plans for the latest installment in his Dream Erosion series, but the results "actually sucked." Thomas candidly told us the first go at the album sounded like "somebody made it in a week while they were trying to figure out a new piece of equipment." That week of fumbling with unfamiliar gear, however, was fruitful as an exercise in trial and error. Those clumsy experiments became the foundation for Critical Violets, Dream Erosion Pt. VII—Thomas's most compelling electronic work to date.

Behold the learning curve as creative space. There's a specific zone between ignorance and mastery where artists have yet to learn what they're supposed to do with their tools. Hip-hop production was practically founded on this—Marley Marl's SP-1200 memory constraints forced him to chop samples into fragments that became golden-age hip-hop's masterworks. The Roland TB-303's "wrong" bass sounds became acid house precisely because the machine wouldn't behave. Thomas's tape machine episode fits this tradition of studio stumbling, and he recognized the value in his failures and chose to build upon them.

Then there's Thomas's broader philosophy of systematic subtraction—"so much better without the drumkit," he realized, "even better without the bass, so much better without the singing." Stripping away musical elements was an act of strategic unlearning, especially for someone with a background in playing in traditional indie-band trios or quartets. Let's think of John Cale abandoning classical training for electric feedback, or Brian Eno moving from Roxy Music's flamboyant maximalism to ambient abstraction. Thomas's "drumless" Dream Erosion series is a return to productive confusion, tossing aside mastery for an ongoing negotiation with limitation.

Playback: Rhythm and Echo — Adrian Sherwood and Style Scott's Dub Revolution → Dub production techniques distort traditional equipment functions—delay units and reverb machines lead the way rather than being relegated to background treatments. Adrian Sherwood's commitment to using the same Lexicon 224 and AMS units for forty years is no different from a guitarist with the same go-to instrument for his or her musical career. It's also a deliberate refusal to chase technological advancement for its own sake. (PS: Adrian Sherwood has a new solo album on the way!)

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

It's like Aho Ssan and Resina dissolved into their music as they collaborated remotely through video chat. "Sometimes during our improvisations or live performances, we couldn't even distinguish who was playing what," Aho Ssan tells The Tonearm. But hidden within their collaboration, and facilitating this dissolution, was a third participant; the imperfect network itself had become their silent collaborator. Every time Resina's processed cello was digitally and remotely passed from Paris to Warsaw, compression algorithms subtly reshaped her timbres. Packet loss introduced microscopic gaps that became part of the rhythm. Automatic gain control systems responded to their combined dynamics in ways they didn't expect, creating a feedback loop where the technology became a co-producer.

There was a subtle bit of time travel, too. Network latency, typically measured in 20-50 milliseconds, meant they couldn't truly play "together" in the traditional sense. Instead, they were always responding to each other's past while anticipating the future. Resina's bowing techniques had to predict where Aho Ssan's electronics might be heading. Aho Ssan's spectral manipulations responded to cello phrases that had already exited the digital pipeline. The disorienting delay became a crucial parameter in their compositions.

This made the pair's intended "ego death" a spiritual and technological reality. The network had dissolved the boundaries between individual and collective creation, and it's difficult to locate the source of artistic agency. Each participant's internet connection, audio interface, and room acoustics became an uncontrollable part of a collective instrument. Unconsciously, the duo learned to work with the network's shortcomings, surrendering to the compression artifacts and latency delays that brought as much to the album as Resina's "scratchy bowing techniques" or Aho Ssan's granular synthesis.

Playback: Imagination is the Instrument — A Conversation with Josh Johnson → Like Aho Ssan and Resina, Josh Johnson also views his technological tools as a creative partner. He runs his sax through effects pedals, which respond to his input in ways that are unexpected and sometimes self-generated. To Johnson, these surprises and limitations become "access points to creativity."

The TonearmChaim O’Brien-Blumenthal

The TonearmChaim O’Brien-Blumenthal

Cult Liverpool band Half Man Half Biscuit bypassed a potential stepping stone to success when they skipped a television appearance to watch the Tranmere Rovers play. Was this punky contrarianism? Or just part of a four-decade commitment to cultural resistance rooted in post-industrial defiance? Liverpool has always operated as if it existed in its own universe, producing bands that initially puzzled London's tastemakers. The Beatles conquered the world but never stopped being Scousers; Echo & the Bunnymen, too. Half Man Half Biscuit were proudly not from London nor of its mindset, treating cultural legitimacy as something that flows from working-class clubs, not television studios.

This geographic stubbornness found its apotheosis in Manchester's Factory Records, which built an entire counter-infrastructure including The Haçienda, Peter Saville's designs, and independent distribution networks. Then there's fellow Manc Mark E. Smith of The Fall, who made contempt for London part of his artistic persona. Across the Atlantic, Detroit's techno pioneers operated similarly, with Underground Resistance making the city's post-apocalyptic landscape a central part of their sound and politics. Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson created entire genres without acknowledging New York's established scenes. Cultural power was held tight, kept local.

Half Man Half Biscuit's sixteen albums from Merseyside hammer this home with localized references and in-jokes. That's how you build community among insiders, perhaps creating something sustainable that doesn't require geographic validation. It's endurance without expansion (or, in technology brother lingo, growth without scale), and the lads who shook the Wirral understand that sometimes the most punk thing possible is staying exactly where you are.

Playback: Web Web's Blueprint for Spontaneous Kosmische Jazz → Roberto Di Gioia described to The Tonearm how Web Web play by their own, record label-defying rules: "We are not a working band. We see each other once a year, record an album, and everyone goes their own way." There's no expectation of endless touring, promotion, or the churn of 'content'—this German collective has built their entire practice around rejecting the conventional music industry model.

The Hit Parade

- The Northern Irish electronic duo Bicep have ventured into even cooler temperatures with TAKKUUK, an original soundtrack that accompanies an immersive installation exploring Indigenous Arctic communities and climate change. Andy Ferguson and Matthew McBriar's atmospheric production, which can be both beatless and rhythmic, incorporates field recordings from Greenland’s Russell Glacier and Indigenous voices singing in Inuktitut and other languages that are facing extinction alongside the Arctic ice. The pair realized this project with outstanding vocalists, including Katarina Barruk, Andachan, Sebastian Enequist, Tarrak, NUIJA, Niilas, and Silla, all helping us imagine vanishing worlds through sound. Field recordings from Greenland and the vocal talent help the songs flow along beautiful stretches, like drifting waters, though clubbier moments, like “Taarsitillugu,” may not resonate as deeply as the more expansive pieces. Yet the inclusion of Indigenous voices adds distinction to the few DJ-friendly tracks, although these contributions may only elicit curiosity rather than recognition from the dance floor. Or maybe that's part of the point? To their credit, Bicep navigate the collaborations carefully, letting Indigenous voices lead while their production remains respectfully minimal. TAKKUUK opens with "Alit," a glacial tone-setter that articulates the light reflecting off ice sheets through glistening electronics, and the album imagines the majesty of threatened landscapes with a contemplative pace. For me, the closing "Sikorsuit" serves as the album highlight, merging clubby breakbeats (though more of the 'back to mine' variety) with glorious vocals and swelling synth pads, effectively summarizing this project's nature in a single piece. The tone of this track, and TAKKUUK as a whole, is melancholic and triumphant—two moods that might seem at odds but make sense here. As the installation and its accompanying album ask observers to consider their complicity while honoring Arctic resilience, that tone is warranted—and hopefully, the project is eventually somewhat triumphant in realizing its aim. This one deserves a listen.

- Short Bits: Saxophonist and composer Sean Imboden is our guest this week on the Spotlight On podcast, and he tells us all about what it's like leading a 17-piece jazz band. It doesn't sound easy! • Despite this lukewarm review, I'm sort of pining for "the world’s first medieval electronic instrument." • Here's a good series from Drowned In Sound highlighting artists from the Ukrainian music underground. • A great playlist from the New Sounds radio show featuring 'Acoustic Versions of Electronic Music' — alumni of The Tonearm Taylor Deupree and Joseph Branciforte are included. • This is such a beautiful cover version of My Bloody Valentine's "Lose My Breath."

A Shout from the 'Sky

Deep Cuts

Prolific keyboardist Roberto Di Gioia has earned ‘friend of The Tonearm’ status due to his multiple appearances in our universe (as well as being a friendly and engaging guy). In addition to the Web Web interview mentioned in the 'Playback' section above, Roberto joined us on the podcast twice—once with electronic producer Max Herre, and then again with the enigmatic trip hop pioneer Peter Kruder. So it was only a matter of time before I asked him the magic question: What’s something you love that more people should know about?

I love Klaus Voormann, and I think more people should know more about him. He played bass on so many important songs, including "Imagine" (!), "You're So Vain" by Carly Simon, and "The Mighty Quinn" by Manfred Mann's Earth Band. The song that got me into music, and which was always playing on the radio back then, was "My Sweet Lord" by George Harrison. Klaus plays bass on it. He recently told me that he wasn't a bassist at all and had just muddled through all the recordings and sessions. What an incredibly modest man!

He was (and still is) a great graphic designer who also created wonderful graphics/prints of the Beatles. I recently purchased one of his prints, a picture of John Lennon, commemorating the anniversary of John Lennon's death.

In 1966, he created the famous and groundbreaking Beatles album cover for Revolver. He told me the story of when he presented it to them: the Beatles stood in a room, and no one said a word. He wore a black turtleneck sweater and sweated profusely. Then, Paul was the first to say something like, "Pretty good... I like it." Brian Epstein stood at the back by the window and cried. After the mood lightened, Klaus asked Brian why he was crying. Brian replied, "Because this is exactly what I've always been looking for: the connection between this music and the fans."

I also just learned that Klaus Voormann produced TRIO, who were a big part of my high school soundtrack. Da-da-da!

Things That Make You Go Hmmm...

Sign up to receive the Talk Of The Tonearm newsletter in your inbox every Sunday. 💥

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Run-Out Groove

Thank you for reading. I hope you learned as many fun things from this edition as I did putting it together. That's definitely a perk of producing a weekly newsletter like this. I mean, until this weekend, I had no idea how one could shake the Wirral. I love it.

As always, please share this newsletter with a friend who enjoys learning things while listening to cool, nerdy music. You could also post the 'View in browser' link at the top on a social media feed or two. That would really shake my Wirral, har de har har. I'm also eager to hear what you think and if you have any comments about what we're doing at The Tonearm—reply to this email or contact us here.

Oh, crap. It's August. How did that happen? I'd better get a move on. Stay safe, always look for the shady spot, and keep on hanging on. I'll see you again next week. 🚀

Comments