I have a rule of thumb for placing new and recent compositions into the historical classical tradition, and it has to do with recordings. If a work is from the contemporary era and has one single (debut) recording, it is 'new music,' and once (if) that work gets a second recording, it's part of the repertoire. That is a dividing line that might as well be a chasm, considering how few such compositions get even one recording—but once that second one comes, it's no longer specialized music but something that musicians and ensembles anywhere can pick up and play. An ideal example of this is Music for 18 Musicians, which was at first something so specialized that only Steve Reich and Musicians played and recorded. Then Ensemble Modern released their own recording of it in 1999, Boosey & Hawkes decided to publish a performing score, and it became a part of the repertoire. That's the rule, and I make it.

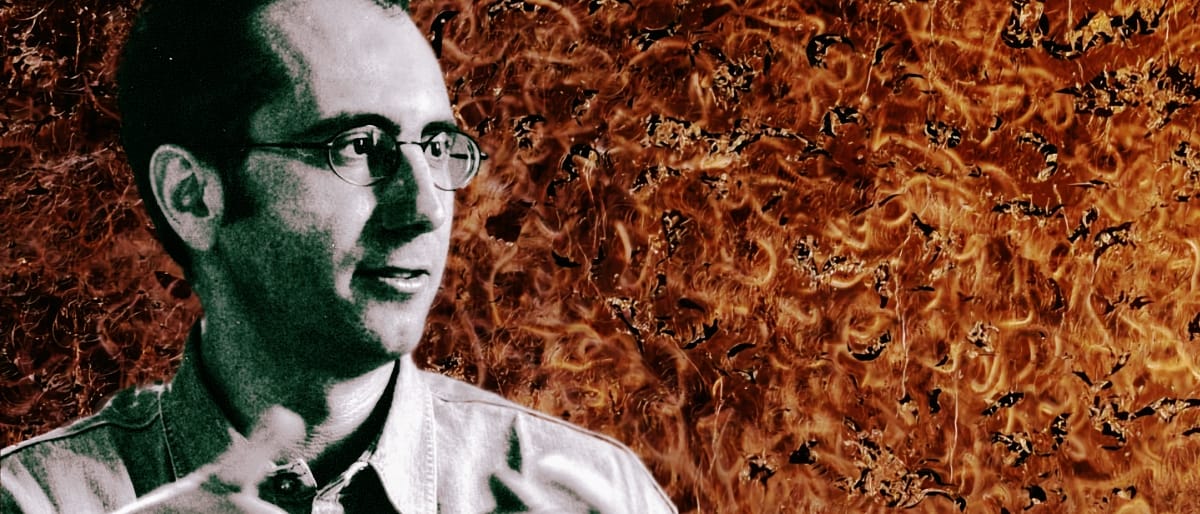

So, welcome to the classical tradition, Fausto Romitelli! The occasion of this was the 2025 release of Fausto Romitelli: An Index of Metals, performed by SMET - Electronic Music School, AltreVoci Ensemble, and soprano Livia Rado, all conducted by Marco Angius, and on the Kairos label. This is actually the third full recording of this work, after a 2005 release from the Ictus Ensemble and one from the Ensemble Miroirs Étendus in 2022. It's an unexpected but avidly welcome step for one of the most original voices in contemporary classical music. This is historically important and also melancholy, as we'll never hear from Romitelli again; he was felled by long-term cancer in 2004, only forty-one years old.

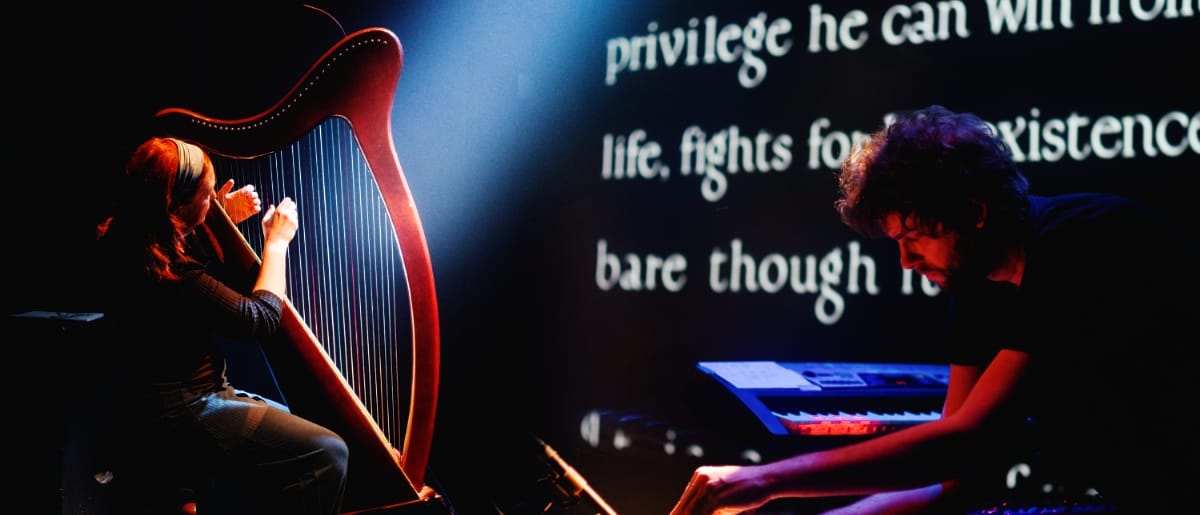

An Index of Metals is scored for a soprano voice and a chamber ensemble that includes a sampler, electric guitar, and bass. Live performances can include visual projections. It's Romitelli's final completed work and is a penetrating example of his aesthetic. As he explained, his goal was "to realize a total, violent and visionarily hallucinatory multisensory experience by immersing the audience in a direct reception of acoustic-visual matter." Romitelli used music and media—sound, text, video—to achieve Rimbaud's "derangement of the senses." As the Kairos liner notes point out, An Index, and Romitelli's other music, make a "secular ritual," where the audience has "the sensation of losing themselves beyond their bodily limits."

This starts immediately with a sound that carves out a space that is 'other,' not the one you started in, in your chair at home or in a theater. It is a direct quote of the opening sound of Pink Floyd's "Shine on You Crazy Diamond," just the opening G minor sonority extended in time, nothing else. The instrumental music opens with the evocative and mysterious vrooming sound of a vinyl album spinning up on a turntable to full speed. We were one place before, now we are in another place. Notes shimmer into being, cycling waves of sound that build in volume and, perhaps, threat. The text from writer Kenka Lekovich, in three "Hallucinations," outlines a journey into the underworld, or to some distant and non-existent region in the mind.

A full performance with projections makes this a video opera, one of the few truly formally and structurally experimental and innovative contemporary operas. But the music by itself has substantial narrative power and force. As the piece goes along, each vocal section rises like an announcement before slowly drifting down, down, down. It feels like the players are trying to escape the slow but inexorable pull of a black hole. There are power chords from the guitar, siren-like swirls from winds and strings. It sounds free, almost chaotic, but it's just as Romitelli put it down on paper. And in sound and cultural place, it has as much to do with psychedelic rock and drug experiences, even rave culture, as what we normally think of as classical music.

This is Romitelli's voice, and some of his other titles show where his head was at: Acid Dreams & Spanish Queens; EnTrance; Cupio Dissolvi; and his equally stunning Professor Bad Trip. An Index of Metals is a superb example of his compositional craft, his ability to take what was in his imagination and express it for the listener. He reached this point through a fairly standard path: music school and studies with other composers, specifically the great Italian modernist and teacher Franco Donatoni and the spectralists Hugues Dufourt and Gérard Grisey. He was importantly inspired by the non-conforming irreverence of György Ligeti, and also spent two years as a research composer at the Institut de recherche et coordination acoustique/musique (IRCAM) in Paris.

Spectralism seems to have shown him a way toward an organic sound, but Romitelli was a non-formalist. He didn't shape music with any clear structural regularity, nor did he spin out overtones and build an architecture out of them, like the spectralists. In his biographical essay on Romitelli, Pierre Rigaudière explains, "Romitelli was drawn to the energy of rock music, although he criticized its lack of harmonic inventiveness, and in particular to the new acoustic horizons being explored in psychedelic rock in the 1960s. To him, these trends in music converged in certain ways with spectral music . . . in terms of the sounding result. Once one has noted how he placed these convergences at the center of his approach, it is easy to understand why the composer could not be satisfied with any simple compromise between the two legacies—such a compromise would resemble a kind of New Age aesthetic more than it would any real 'compositional work.' Romitelli instead felt himself obliged to work toward a kind of deep hybridity."

He found that hybridity. It feels like the hard-earned results of an immersive journey—he did the most difficult thing, which was to spin music out of his mind, with personal intuition, and put it together in a way that feels like it makes sense emotionally, even if we can divide it up into meter, rhythms, four- and eight-bar patterns. There is a taste for the power of pure sound and timbre in his work, and especially for the visceral, vernacular communicative power of rock music. He's one of the very, very few composers, like Erkki-Sven Tüür and Jacob TV, who can convincingly make music that is clearly in the classical tradition and can also feel convincingly like rock. Romitelli's music is as if Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Schumann hung out in the same opium den, at the tail end of both rock and classical form.

Romitelli's personal voice put him at the avant-garde edge, the place where music pushes forward to a point where the larger tradition will eventually reach. But his concept, channeling popular aesthetic, mores, and sensibilities into classical composition, wasn't new. In fact, he was part of the long history of the Western music we've come to call, since Beethoven, "classical." Roughly, it is a notated music written by composers for other musicians and ensembles to play, and, since Beethoven, it has been a musical culture that has looked to the past more often than to the present. That last aspect took generations to develop—audiences eagerly anticipated the next new work from Brahms, Strauss, Stravinsky, etc.—and was codified in an unintended but pernicious confluence of preserving music on audio recordings and the academicization of composition and institutionalization of classical music since World War II. The modern result was a segregation of classical music as something out of the day-to-day mainstream experience of the general public, an audio museum of historical aesthetics and mores, promoted as a respite from the streets.

In the long scheme of things, this has been an ahistorical deviation from both how this music was made and its place in society. The actual history of classical music, the ancient tradition, shows that segregation to be utter, artificial nonsense. In the 15th century, or maybe the 14th, some anonymous musician made a song titled "L'homme armé" that became exceedingly popular in late Medieval Europe. It's a secular song about "The armed man," who "should be feared." Composers from the 15th to early 16th centuries used the original tune as the basis for masses, with famous ones from the most important musicians of the epoch, including Josquin, Palestrina, and Guillaume du Fay.

Again, at the time, none of these composers had any idea what classical music was or would be; they were making new music to be performed for liturgical occasions. They heard music around them and found something in it to use as their own material. Other than the preciousness we assign to music from the distant past, there's nothing unique about this. Since the dawn of music, the medium and the way it has developed through time have been an accumulation of ideas, influences, and possibilities. A musician creates a phrase or lyric; another hears it and responds to it, reworks and recontextualizes it, adds to it, and passes it on to the next musician.

Music is a continuum, not a set of discrete categories. So when a classical composer incorporates music from the metaphorical streets, it's as commonplace as can be. Mozart did it, Beethoven did it, so did Mahler and Stravinsky and Berio and many, many more. It's rare when that doesn't happen. The indie-classical composers made a movement of it earlier this century. Why their music goes down easy and gets books written about it, and why Romitelli is a challenge to even find, has to do with the source of the popular music. And it goes back to form.

Song-based music in regular forms—verse-chorus structures that dominate popular music, identifiable meters, and populist beats made for dancing, or at least bouncing—are the norm. Their appeal is clear, because they are appealing! And they take good musicianship to put together. It's harder to write a good song, to fit words, chords, melody, and rhythm together in a way that works, than to write a good sonata, which has a fairly uncomplicated structure by comparison. But the problem with formal regularity is that it can become a trap, and when composing music that fits the classical tradition, using pop song formats and striving for that appeal is a dangerous trap. Regular form and structure, done too often, lead to regular and predictable music, a short step from the circularity of pop music.

Romitelli may have grounded his music in the popular appeal of rock, but he never chose the most popular style. Taken seriously and extended, psychedelic rock is a path toward what Rigaudière characterizes as the composer's desire "to destabilize the listener's experience of his music." Repetition is ubiquitous in music, especially pop music, and there's repetition in Romitelli's work, but instead of using it to build something in time, he uses repetition that descends in pitch, mood, and quality to model disintegration, loss, even despair. Even though there is text in An Index, the music goes beyond what mere words can capture and gets to Romitelli's personal values in music; he's not reaching for the listener but showing the listener.

"Romitelli was clear about what he perceived as his role as an artist," Rigaudière states. The composer was representing the "world's violence, he was taking a specific stance in that world, one aspect of which was resisting standardization." There's a paradox there, or several: Romitelli was inspired by rock but desired the harmonic complexity of late-20th-century classical compositional tools; he used repetition against standardization, repetition as erosion. It was the creation of something out of nothing to show how something turns into nothing. Still, if Romitelli was showing us something uncomfortable, it has the reassurance of both personal truth and the simple glories of music-making. And he also showed us that the fundamentals of the old ways never go out of style nor lose their values. This is how we get from the past to the future.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmGeorge Grella

The TonearmGeorge Grella

Comments