When first announced, new technology can be seen as a double-edged sword of two extremes. On one hand, it's an overpromised solution to cure any problem one has, or it can wholly be blamed for the downfall of the human race. These sentiments are observed satirically in Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu's 1959 comedy film Good Morning, where he explores encroaching technology in post-war Japan. At times, he approaches it with a childlike sense of wonder, whilst under the surface, there lurk fears about the future of Westernization. Focusing his lens on the subject of television—and, to a lesser extent, other new tech like dishwashers—Ozu illustrates how consumerism affects a culture, as well as providing a touchstone for modern-day viewers to examine their own fears of progress.

Ozu doesn't waste time and delves into his theming in Good Morning immediately. From the first shot, he lingers on power lines before we see students barely visible, walking on a hill far in the background. They're not easily seen because the community housing development where the children live obstructs the viewer's line of sight. Perspective is played with often in Good Morning, and here it is used to connect key themes of the film in an instant: communication/technology (the powerlines and village) and the future of the country (children).

After these establishing shots, we are whisked into Japanese rural life from multiple perspectives. First, we see boys challenging themselves to pass gas on command after being pushed on the forehead with an index finger, then we see two women gossiping back and forth about where the local women's club dues have ended up. In both of these interactions, the washing machine becomes a key figure. With the boys, one of them tries too hard to fart and defecates in his pants by accident. His mother (Mrs. Haraguchi, played by Haruko Sugimura) expresses to her child that, although she's glad to have a washing machine, she didn't get it just to wash the boy's underwear and pants. This same Mrs. Haraguchi also seems responsible for the missing dues that the other women are gossiping about. Because washing machines are expensive, the women presume Haraguchi must have embezzled the funds from their dues to purchase it. Though all of these interactions are presented as relatively light-hearted, they also convey contrasting fears of technology. Those who adopt early are often seen as rich or as having done so through ill-gotten means, and they also use their new inventions sparingly, as if fearing they will overtake their lives.

However, the washing machine is a side character in Good Morning, with much more screen time given to its main star, the TV. Two children of the Hayashi family—older Minoru Hayashi (Koji Shitara) and younger Isamu Hayashi (Masahiko Shimazu)—beg their parents for a TV set after frequently visiting their neighbors who have one. They even sometimes skip their English lessons, much to their parents' dismay. Conflict ensues when the parents outright refuse to buy one for their children. They have two major reasons—one comes up after their outright refusal, and the second comes later in the film. First, their bohemian neighbors are strange and seemingly a bad influence, as they wear pajamas all day, and the wife is a cabaret singer. The logic here—if they're a bad influence and own a TV, it can't be worth getting one. Second, later in the film, the Hayashi family father expresses something he read to others as a reason for not wanting to adopt the new medium—"TV will create 100 million idiots."

Regardless of these reasons, the children do not take their parents' refusal easily, and they act out by throwing temper tantrums before being scolded by their father. After this, the two commit to silence and hunger strikes to force their parents to rethink the decision. Seeing these children struggle to get "the new cool thing" feels ultimately universal: in every new age, there is some seemingly new technology that children want and parents are apprehensive about. Whether they be video games (like the Nintendo, Sony PlayStation, or beyond) or even modern-day smartphones, there is always a weighted cost parents have to balance between doing what's right for their kids, while also trying not to isolate their children from their peers.

This struggle between children and their parents in this rural area of Japan illustrates a consumerist culture in its infancy. When this film was set and released in 1959, Japan was just beginning a period referred to as the "Japanese economic miracle," a bubble in which the country's national income recovered to pre-war levels. This flow of money created new "needs" such as recreation and entertainment. This is where inventions that weren't particularly asked for, like the TV, come in. Though Ozu was unable to foresee future issues, such as what happens when there are no more needs to be created—a vital problem of late-stage capitalism—he documents its beginning in a way that feels unintentionally like a time capsule. The cycle begins slowly when consumers like the Hayashi family feel pressure to opt in to questionable technologies like the TV, and it speeds up when more are created or a new update arrives. Eventually, the cycle consumes itself much like an ouroboros.

Themes of communication and politeness run countercurrent to this consumerist documentation. One of the first hints of this comes from the film's title: Good Morning. Several times throughout the film, pleasantries are exchanged between peers within the village. Though shown to be important for keeping up appearances, these expressions are also often portrayed as empty and meaningless. A particularly poignant example of this involves an unrequited romantic relationship between Keiji Sada (Heiichiro Fukui) and Setsuko Arita (Yoshiko Kuga). It never develops because both repeat substanceless variations about the weather to fill the silence rather than say anything important. Other times, these vapid exchanges are more directly expressed when the young Isamu Hayashi repetitively says the English words "I love you" as a sort of goodbye. Older brother Minoru Hayashi builds upon these concepts when, during a tantrum, he exclaims how these pleasantries have become useless and unimportant, as they are utilized just to fill the silence. And even if one keeps up appearances, the gossiping women throughout the film illustrate that backstabbing talk may be happening behind closed doors, or being polite may even cost you in multiple ways, such as when door-to-door salesmen weaponize it to gently nudge people into buying their wares because of the culture's fear of being perceived as rude.

Ozu highlights these expressions throughout the film, ironically conflating them with Japanese fears of the newest technology: the TV. People like Keitaro Hayashi (Chishū Ryū), the Hayashi father, rail against TV because they believe it is vapid and lacking in substance, yet they are also often proponents of maintaining social decorum by regularly using empty phrases. This is why characters like Minoru call them out on this seemingly pointless behavior. What's the difference, Minoru poses, between engaging in senseless entertainment or meaningless repetitive dialogue daily? If one is completely acceptable, why isn't the other?

There's another key aspect of politeness highlighted in Good Morning that relates to the TV as well—maintaining a sense of quiet. Illustrated best in the Hayashi family, when the children scream, complain, and act out, it is a key point that the father builds on in his argument when he scolds Minoru. He expresses that a boy his age should be quieter and less talkative. Though Minoru obeys, it's through malicious compliance: he says nothing and coerces his brother into doing the same.

When connecting these communication aspects with technology, viewers can see how Ozu illustrates another key reason the television is such a direct threat to Japanese culture: its loudness. Unlike more silent activities such as reading, the television demands one's attention, similarly to how Minoru demands it through temper tantrums. Through its loudness, it also interrupts, as neighbors do in the film, whether to return a borrowed item or to accidentally wander into the wrong house after a night of drinking. If the Hayashi parents give in and buy a TV set, they are inviting a permanent interruption into their home.

However, Ozu also shows that maintaining silence doesn't necessarily create a more polite society. The two children, in trying to be more silent like their father asks, completely snub one of the neighbors by not greeting her, leading to a slew of miscommunications and fears. Then, there's a point later where the parents need to supply their children with lunch money, but due to the children's silent strike, it becomes an ineffective game of charades as both Isamu and Minoru are unable to communicate their needs.

Then, there's another example that runs concurrently with communication and politeness: self-isolation. Although the TV can bring people together, as seen earlier in the film when the Hayashi sons go to watch it, it can also eventually pull a community apart. This is because if each family adopts the technology, they separate themselves from the larger community. Though the community is currently bustling in Good Morning, it's easy to see a future where all the families have their own TV sets and the only interactions happen between those watching. It becomes ironic—beyond the TV's primary goal of entertainment, it was sold as a method to help users connect with events happening around the world. However, the widespread adoption of this technology isolates each person from the community closest to them.

In our modern day, social media and smartphones have similarly affected local communities. Both were sold as ways to connect us to the modern world, but they have further isolated us into bubbles of communities that only agree with us. Equally, they suck us in and away from those we are often currently spending time with. As we retreat into our curated, hyper-specific worlds of algorithmic intent, we lose a sense of our former relationship and of space for a digital, impermanent universe. Then, additionally, they become a fear-riddled decision parents must make—when does one allow their children to succumb to this reality? Even if they choose to delay, how long will it be before they are exposed anyway?

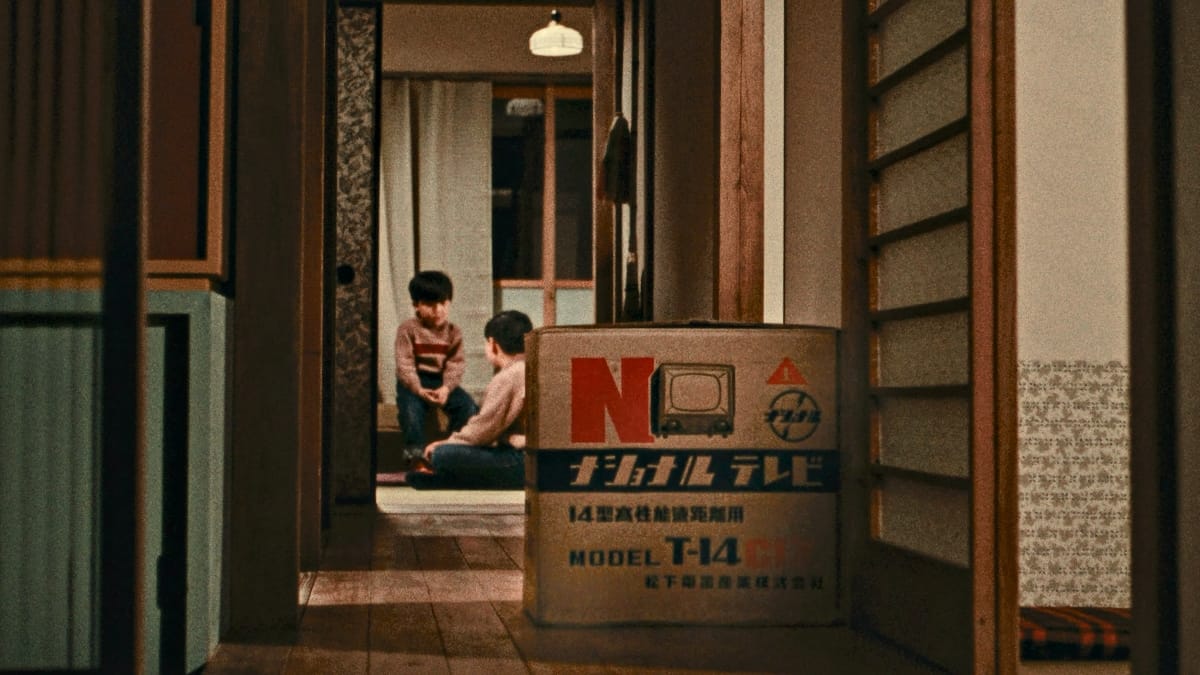

This last question comes to a head near the end of Good Morning when the Hayashi children run away. They are eventually found outside a station watching television, illustrating that if parents try to bar their children from adopting a technology, children will still find a way to get their fix, even to dangerous degrees. Though nothing actually happens to the children from their attempts to watch TV in Good Morning, there is still the underlying subtext that their running away could have. Because of these reasons, the Hayashi parents give in and buy their children a TV. As the two break their silent strike and scream with glee, their father stops them briefly and tells them they are getting too loud. However, the younger Hayashi son, Isamu, subverts this when he says that his father is joking, and his face gives him away. Here, we see the front of Eastern silence dissolve into modern technology and Westernization. Though a joyful scene, the TV is never unboxed upon the film's exit, as it sits in the middle of the hallway.

Specifically, this shot of the TV sitting there unboxed is purposeful. It looms, like how its future looms over the end of the film. Like the Japanese people, Ozu doesn't know the TV's eventual impact. This scene between the Hayashi children and their father illustrates the breakdown of barriers between parents and their children. Similarly, it represents the eradication of separations between East and West, isolationist countries and globalization, and a pre-consumerist world with an all-encompassing one. Though in 2025 viewers of Good Morning have a more concrete understanding of how television has impacted their daily lives, noting that it hasn't destroyed or saved the human race, they will still find similarities with newer technologies such as the internet, smartphones, and, of course, AI. Each of these has been predicted to have one of two similar outcomes: a panacea for the human race or the eventual expression of its destruction. Or perhaps in time, they will become a third option similar to the Hayashi TV—a backdrop element of our world, replaced by newer (and maybe more threatening) technology.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmWilliam Slyter

The TonearmWilliam Slyter

Comments