Surprise! It's a midweek appearance of our Talk Of The Tonearm newsletter. This is the place where I aim to dissect the stories that recently appeared on our online catalog of "unexpected music and culture." It's a fun job, but somebody's gotta do it. There's a lot of amazing stuff to get into (and I need to get this newsletter out), so I'll just jump into it:

Surface Noise

Casey MQ talks a lot about hauntings in Arina Korenyu's profile of the thoughtful musician. Some of these hauntings are figurative—"feeling less alone, cuz all my friends are ghosts," he sings at one point—but Casey also references depictions of literal ghosts with his song "Casper." That's Casper the Friendly Ghost, a character that turned the typical idea of a ghost on its head. Casper rejects haunting and terrifying; he's friendly. Casper accepts and perhaps even relishes his position. Casey cleverly employs this as a metaphor: "I loved the idea of talking about friends through that lens—mixing the childlike quality of the story with the maturity of the concept. It's about that feeling of disappearance, which I think you can only truly understand with time."

The character of Casper can be seen as a spirit of cultural resistance against dominant narratives about death, loss, and the afterlife. Rather than being defined by the tragedy of death or existing to frighten the living, Casper seeks connection and community. He's also a mainstream icon ripe for countercultural recontextualization. Casey's adoption of the friendly ghost metaphor connects to how underground scenes (like electronic music communities) often embrace and recontextualize mainstream symbols from the artists' childhoods. Casper is a spectral presence in popular culture—not fully embraced by the mainstream but persistent and influential as a cultural memory.

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Playback: This reminds me of author Erik Davis and his fascination with the historical record of acid blotter art. Of course, blotter art regularly adopted the images of mainstream cultural signposts, from Snoopy to Mr. Bill. I'm sure there's Casper blotter paper out there somewhere. Oh, and I must also mention this song about Casper the Friendly Ghost.

It was a thrill for Sylvie Courvoisier and Mary Halvorson to join us on The Tonearm for a revealing conversation about their duo album Bone Bells. An especially interesting part of the conversation touches on the role of guitar and piano treatments—effect pedals for Mary, prepared piano for Mary—play in performance and composition. Mary states: "I might play an effect on a piece one night and not play it the next night. But in many cases, I think my effects and Sylvie's prepared piano will kind of become part of the composition. Like we'll choose moments for it, and often that will be how we play it." Mary even refers to these effects as the band's "third person."

Prepared piano is a fascinating technique—it's an approach that transforms the familiar sound of the piano into entirely new sonic territory. This involves directly plucking or hammering the strings inside a piano, sometimes with specific objects (screws, bolts, rubber, coins) placed at precise positions between specific strings. The preparation becomes as deliberate as choosing which notes to play.

Though mostly associated with 20th-century John Cage compositions, the prepared piano is making a comeback. For example, Nils Frahm's breakthrough 2011 album Felt was created by placing felt on the piano hammers to create a distinctive, intimate sound that has become his signature. And then there's Volker Bertelmann, known as Hauschka, who takes prepared piano in a dramatically different direction. He employs a curious array of objects, including "super-magnets, art erasers, rubber tubing, Tic-Tac boxes, ping-pong balls, duct tape, aluminum foil, leather straps, marbles, and vibrating sex toys" to radically transform the piano's timbre.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Playback: On The Tonearm, LP profiled a Munich trio that's so enamored with the prepared piano technique that the band goes by the name Prepared. Their terrific album Module owes both to Steve Reich and Germany's infamous nightclub scene.

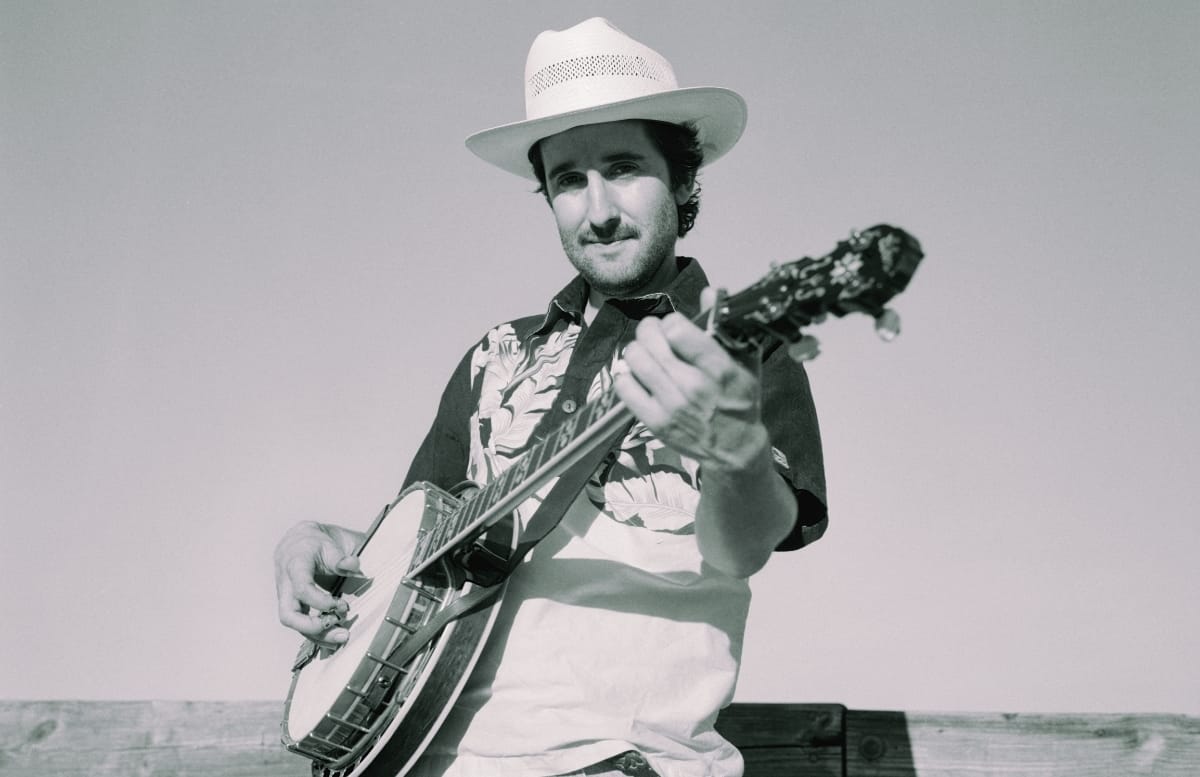

This week, there’s a terrific interview with bluegrass historian and banjoist Max Wareham, courtesy of contributor Sam Bradley. Max previously published a biography of Rudy Lyle, "the unsung hero of the five-string banjo," and has followed that with his own album, the wonderfully named DAGGOMIT!. Max's main instrument is a banjo created in 1927, which makes it just a hair under 100 years old. "The one thing that draws me to playing an old instrument is that it is way older than I am, and it's going to live longer than I will, too," Max says. "I'll probably have this instrument my whole life, and there'll come a day when I'm not here anymore, but the instrument still is."

Max is also a budding archaeologist (as if he needed more on his CV), and vintage instruments are purported to possess a sort of "tone archaeology." As the wood ages in Max's nearly 100-year-old banjo, its cellular structure crystallizes—lignin (the complex polymer that gives wood its rigidity) gradually transforms through oxidation, while resins within the wood harden and distribute differently throughout the grain. These molecular changes create acoustic properties that newer instruments, regardless of craftsmanship, simply cannot possess. There is an elusive "pre-war tone" that keeps bluegrass musicians hauling irreplaceable antiques to performances despite fears of road wear and baggage claim mishaps.

Of course, there's always the possibility that this vintage tone is in musicians' heads rather than their ears. Blind listening tests comparing century-old instruments to modern high-end replicas often yield mixed results, with listeners sometimes unable to consistently identify which instrument is of rare vintage. This doesn't invalidate the experience of players like Max, who find inspiration in knowing their instrument carries a century of musical history within its wooden body.

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

Playback: In an earlier piece, Sam Bradley spoke with Portland musician James Cook of Captain's Audio Project about his 1931 National Tenor Resonator guitar, likewise an important part of James's sound and creative inspiration.

We featured Calgary saxophonist Daniel Pelton and his powerful work with Violins of Hope. Daniel honored the humanity of Holocaust victims and survivors by transforming numerical tattoos from concentration camp prisoners into musical progressions. The resulting composition was then performed on recovered historical instruments originally played in the concentration camps. Daniel explains: "[The] instrument collection once belonged to victims of the Holocaust, victims of World War II, most of them Jewish, but some instruments with uncertain histories that were just found in the rubble of camps." The Daniel Pelton Collective album Violins of Hope documents the performance and composition.

Like the changes to an instrument over time that affect its "tone archaeology," there's a quality of a vintage instrument serving as a silent witness. When Pelton chooses to employ the instruments from the Violins of Hope collection, he's engaging in a physical dialogue with history. The players' fingers touch the same surfaces that Holocaust victims touched. The instruments' memories aren't stored acoustically but through the power of physical continuity and shared human connection across time. Beyond appreciating the music, we witness a moment when the past is physically present. Memory becomes tangible through objects that connect one human being to another across decades.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Playback: In our interview with the late Susan Alcorn, she also explored how instruments carry cultural memories across generations and discussed her relationship with musical instruments in almost spiritual terms.

The Hit Parade

- The legacy and influence of Arthur Russell live on. Richard King is the author of Travels Over Feeling: Arthur Russell – A Life, a book that collects the extensive ephemera found in Russell’s New York Public Library archive, along with pieces from the personal collections of those closest to him. The Tonearm is psyched to host Richard for a livestream conversation hosted by Spotlight On's Lawrence Peryer. The best part is that you're invited! Join us for this celebration and examination of Arthur Russell on April 22, 2 PM ET and 11 AM PT. It's a free event, but please register in advance. We'll see you there.

- A new music recommendation from LP: Gustavo Cortiñas's The Crisis Knows No Borders puts intricate drum patterns beneath open-form compositions with environmental themes. The Chicago-based drummer creates dynamic musical spaces where Mark Feldman's violin brings exploratory textures against Jon Irabagon's brutish saxophone lines. The ensemble works with striking restraint on "The Man of Flesh and Bone," while "Sea Levels Rising" builds from spare, ECM-like atmospherics to dense collective improvisation. It gets intense. The record is the kind of mix of structured sections and free exploration that draws me in. A representative case is the track "Skepticism," where Miller's guitar effects create electronic textures beneath Cortiñas's polyrhythmic foundation. While overtly conceptual in its environmental messaging, the album succeeds musically through its anything-but-typical instrumental combinations and Cortiñas's compositional approach. The quartet moves fluidly between jazz idioms and contemporary classical influences, especially in the album's contemplative final track, “Meditations on the End of Times.” (LP)

- I listen to far too many podcasts. This week I enjoyed Search Engine's investigation on how a Russian rapper got misidentified as the band Cake on Spotify (it's frustrating how little the digital distributors care about these mixups), an episode of In Our Time on pollination that gave me more than a few "WTF?" moments, and an interview with the regularly enlightening Brian Eno on Life with Machines. The latter ends with an incredibly hokey bit with something called "Blair," but Brian remains a good sport.

Deep Cuts

Prolific saxophonist Noah Preminger was our guest on last week's episode of the Spotlight On podcast. In the course of the interview, he dropped a few outstanding artist recommendations:

Steve Lehman has done a couple of records that have him working with a rapper that I think are really awesome. Just really forward-thinking, amazing compositions. The playing is killing on it. Really love those albums.

Another is an alto player named Godwin Louis. He's got a record called Global that he released a couple of years ago. Godwin is Haitian, now living in Connecticut. I think Godwin's been to every single country in Africa, just on an unbelievable exploration of world music. And you hear it in his writing and his playing. As an improviser, Godwin is unbelievable, and he's a great saxophone player, too. It'll lift your spirits listening to his music.

I'll also recommend is Ches Smith, the drummer. He had a record with We All Break called Path of Seven Colors. It's got Miguel Zenón on it. Matt Mitchell's on it. Great band. It might have Haitian percussionists and singers if I'm getting that correct. Incredible compositions, and I'm a big Miguel Zenón fan.

Run-Out Groove

Pretty cool, right? As always, thank you so much for being a supporter of The Tonearm and a subscriber to this sometimes chaotic newsletter. If you'd like to share this with a friend—just one will do—then we'll perform impressive backflips within the hidden chambers of The Tonearm HQ. Letting friends know about us is the best way to show your appreciation for what we do.

Thank you again, and I'll see you next week! 🚀

Comments