Rain Parade rose out of Los Angeles in the early 1980s as one of the most compelling voices in what would later be termed the Paisley Underground—though like most meaningful artistic movements, the participants were too busy making music to worry about labels. Founded by college roommates Matt Piucci and David Roback, along with Steven Roback on bass, the band developed a sound that filtered California's psychedelic heritage through punk's urgency and the intricate guitar interplay of Television. Their 1983 debut, Emergency Third Rail Power Trip, remains what critic Jim DeRogatis called "among the best psychedelic LPs of any era"—a record that picked up where the Byrds' "Eight Miles High" left off and pushed it somewhere darker and more introspective.

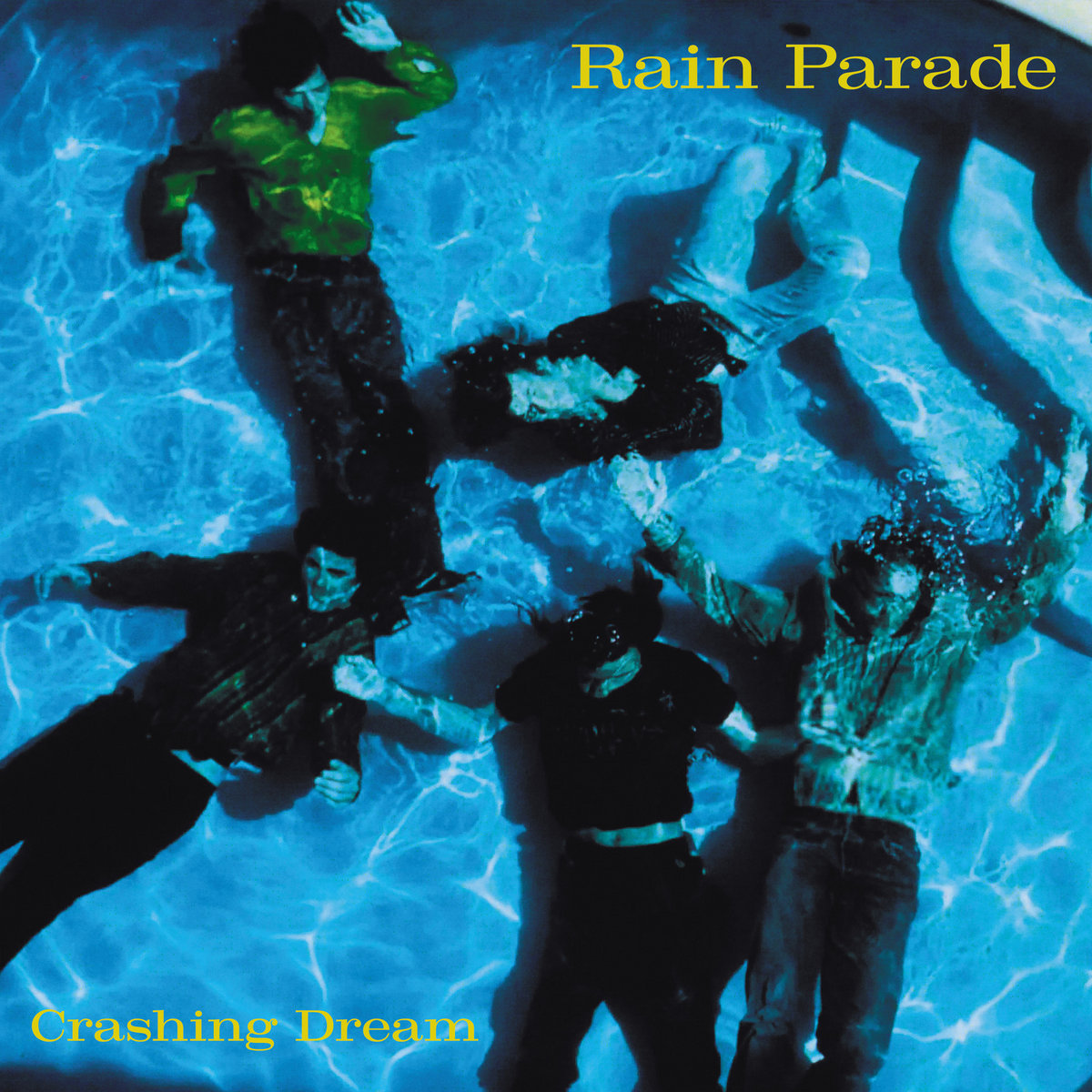

The band took an unexpected turn when David Roback departed after their acclaimed mini-LP, Explosions in the Glass Palace, to form Opal (and later Mazzy Star with Hope Sandoval). Rain Parade regrouped as a quartet, eventually signing to Island Records for what would become their most complex and troubled release: 1985's Crashing Dream. Originally conceived as a double album, the record was trimmed down by label executives who had little understanding of what they'd signed. "It's an old story," Piucci says, "huge label signs band and has no clue what to do with them." The album appeared, disappeared quickly, and became something of a lost artifact.

This month sees the release of a deluxe reissue of Crashing Dream through Label 51 Recordings, run by Bill Hein, the same executive who originally signed Rain Parade to Enigma Records forty years ago. The expanded edition finally presents the album as originally intended: a double LP featuring previously unreleased demos, alternate versions, and live recordings that reveal the full scope of the band's vision during this pivotal period. For Piucci and Steven Roback, who reformed Rain Parade in 2012 and have been steadily active since, the reissue represents both vindication and completion. The band recently released their first new studio album in 38 years, Last Rays of a Dying Sun, proving their creative spark remains undiminished.

Matt Piucci recently joined host Lawrence Peryer on the Spotlight On podcast. They discussed Crashing Dream, the challenges of working with a major label, and how the perspective of four decades has allowed them to finally present these songs as intended. Piucci also reflects on the camaraderie of the supposed Paisley Underground, what sustains Rain Parade after forty years, and how it feels to be making music without the pressures of career ambition—a freedom that has paradoxically led to some of their strongest work.

You can listen to the entire interview in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, flow, and clarity.

Lawrence Peryer: We were brought together to talk about the reissue of Crashing Dream, and I do want to do that, but I'm hoping to maybe use it as a little bit of a launchpad or a framing to talk about what's happening now, too.

Matt Piucci: Oh, that'd be great. I appreciate that very much because it's a dish I made a long time ago. The music, you can keep eating it. Food, unless it's McDonald's, doesn't last.

Lawrence: Well, it's funny you say that because spending a lot of time with the catalog and spending a lot of time with that record recently, I don't think you could necessarily pinpoint when that record was made. When revisiting the catalog, what do you need to do?

Matt: Where to begin? We are heavily involved in the process. First of all, this is out on Label 51 Records, which is run by Bill Hein, who is the guy who signed us 40 years ago to Enigma Records. Crashing Dream was the one that he didn't have, the one that got away. He didn't want to let us go, and we probably should have stayed with him.

For this particular record, we went back to the original. There were some aspects we didn’t particularly like about it. It was a bit rushed, and the producer we got—a nice guy, nothing wrong with him. He just didn't really get us. So there are a few things that we changed. We switched out a version of one song because we had done that with our previous producer, Jim Hill, and we’ve been working with him ever since.

Lawrence: I love the idea of revisiting it with the benefit of hindsight and years, and maybe even addressing things that have always stuck in your craw. That’s a fascinating approach, as opposed to being so ossified about it.

Matt: We certainly could have been a lot more anal. First of all, I don't even know where the hell the multitracks are, but even if we did, we probably wouldn't have done that. We had a couple of songs that bugged us. We slowed one of them down and liked how it sounded better. You know, it's like sausage making—that's why they have doors on kitchens.

Lawrence: Around this time last year, maybe a little later in the year, I talked to Steve Wynn. He was talking about Dream Syndicate forming because they wanted to be the band they weren't hearing. That seems to contrast a little bit with your origin story. It seems like you were just like buds who were simpatico and did the thing. Did you guys have like a rallying cry or a mission?

Matt: Steve's a great dude and a pal. We didn't feel like we were on a mission to do something that wasn't being done. I think that was a bit more subconscious, as I don’t feel that's the way we approach things. I think that, in retrospect, we actually ended up doing something that other people weren't doing. We would play waltz tempos with acoustic guitars in these punk clubs. And people were like, "What the fuck is that?" In that sense, we felt that that was punk. Not that there's anything wrong with punk, but we weren’t doing that. We also loved Chuck Berry and the blues, but we're not going to do that, either. That's not going to be us.

That's very important for any young artist. It's almost what Miles Davis says about how it's what you don't play that's just as important as what you do. And I think he was talking about space, but it's also about the techniques, instrumentation, and everything. Just define your own space in that way.

And we didn't know that until we got out there. We holed up for a year or more before playing, recorded before we even took the stage, and had a single out before our first gig. But I don't recall us thinking, "Nobody's doing this, so we have to." We didn't feel like we were on that kind of mission. And I can dig what Steve says because nobody really sounded like those guys. Steve once said to me that Dream Syndicate were a punk band that played guitar solos. And I'm like, "Yeah, okay,” because they’re a really raw, visceral band. We're maybe more impressionistic.

Lawrence: You know, that early to mid-eighties time to me is so interesting. There’s this idea that it was all synthesizer-heavy European-influenced pop music. But the guitar music never really went away in that era. I think about how George Thorogood was an MTV superstar, or that Dwight Yoakam played in punk clubs. It's all very similar to what I think you're saying there.

Matt: I mean, punk is an ethos more than it is an actual sound. I always thought it was a silly term. There are almost zero American punk bands to me. There are bands like The Clash, The Sex Pistols, and maybe The Damned, and stuff like that. And there’s what came after that's kind of past my time. The bands in New York from the mid-seventies—none of that is punk at all. To me, it's just original songwriting and unique bands who are approaching things differently.

We would listen to that sort of English guitar sound that's all chorusy, and we didn't really like that. A lot of people might say about us that we were kind of “wimpy,” but I never felt like our guitars were wimpy. I mean, there's nothing wrong with pretty music; we liked it and appreciated the introspective approach. However, I never felt like we had wimpy guitar sounds. We like guitars with meat. I guess that's for others to say.

The other bands associated with us, involved at the same time and place—I think those bands, too, have that gritty guitar sound. Even The Three O'Clock—Louis's a nasty guitar player, man. And The Long Ryders, too, or Green On Red, I mean, any of those bands. It's not that watery English kind of sound, which is a little odd because it's funny how things go back and forth. The original rebound of like really gritty American music from the blues. It went over there, and then you got people like John Mayall and that whole group who saw that kind of American music and really got into it, and then it came back here. You know, like obviously Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page and those kinds of guitar players, nasty guitar players.

But then, you know, in the eighties, the guitar coming out of England wasn't that, and maybe because they were rebelling against that being the status quo. The last really nasty guitar player from England would be like Mick Ronson, maybe, who I adore. And then that was kind of old hat to those guys. And then they did this new chorusy thing, and we heard about it, and we went, “Yuck.” We like the grittier stuff.

Lawrence: I think this is a good time to bring up the Paisley Underground. I think less about those types of terms because they're not that interesting to dig into, especially with an artist. I'm more interested in it as a scene. How much of a part of that did you feel you were?

Matt: I think scene is probably a good way of putting it. I think I heard Danny Benair [of The Three O'Clock] say that it wasn't really a genre as much as it was a scene. I once said —and this is true —that all the plumbers in Fontana know each other, too. We were musicians in Los Angeles at a particular time.

There were kindred spirits that we ran with, and it was very supportive. And so when I think of The Bangles and The Three O'Clock and Dream Syndicate, Green On Red and The Long Ryders, and—there are other bands there too. Those were kindred spirits. We felt we were playing the same clubs at the same time. But we also played with the other bands. I guess we were the freshmen, and we played with the seniors like Los Lobos, X, The Blasters, and The Plugz. Tito Larriva [of The Plugz] was a super, super friendly, nice guy, or a guy like Dave Alvin [of The Blasters], who's a sweetheart.

The ones we truly identified with were the people our age. So that is that peer group. Dave Alvin or John Doe, who I don't know, those guys are probably a few years older than we are, and some guys in our scene might be almost that old, but most of us were five to 10 years younger, so that makes sense that we would be in the same position at the same time. So I don't think that term is bad. It's a little silly, but people need labels, and that's kind of the label. Your parents give you a name, you don't—I mean, I guess you can change it, but that's the one you get. It does address proximity and similarity.

Lawrence: It's a good shorthand.

Matt: There's nothing wrong with it.

Lawrence: Where are your best shows right now? Can you still go to the U.K. and see a lot of faces, or do you just go out and do what you do?

Matt: If you talk to Bill at the label, he kind of views Rain Parade like the one that got away. He thinks we should have been bigger than we were. I’m not sure I'd be alive if we were. We may never get 50,000 people to give us $10, but we might be able to get 5,000 people to give us $100. I don’t want to be so crass as to make it about money, but when you're talking about touring, it kind of is. And it's really hard to do now.

So, where I think the Rain Parade people are pretty evenly spread throughout the globe, with perhaps a strong concentration in England. We're never going to draw thousands of people, certainly not now that we're in our sixties, but we have some intensely loyal fans. It's crazy. And the other beautiful thing that makes it rewarding for us is that some of those fans have gone on to be in super cool bands. I mean, when I read the guy from My Bloody Valentine mention us, or when Mani, who's from Stone Roses, tells me how much we meant to them. When we played in Scotland, we met Gerard Love from Teenage Fanclub, and he said the same thing. Then there are bands like Brian Jonestown Massacre, or The Asteroid No. 4, another cool band. That's super, super rewarding.

I’m not sure if it's a career. I had a career, retired from it, and now I'm a musician again, which is kind of fun. But then again, I also feel that many people get caught up in the process of trying to survive, and then they forget what they were there for in the first place. I don't know how a kid does it today. I was lucky enough to be able to—yes—starve, but at least I could jump in a van and play places. There was a way to do that. Gas wasn't so expensive, and there was a network of college radio stations and small clubs that were connected.

And this is before that entire scene, if you will, or that whole network got subsumed into the giant monstrosity of this mono capitalistic thing, where now, you just can't compete. You just can't. I don't know how you even get to bands anymore. There aren't even any bands anymore. If you look at the Billboard Top 200, how many bands are there? Like none. It’s all like individual artists who have been mostly manufactured. I don't know how the young bands do it today. I don't know where they go, where they turn.

Lawrence: I was talking to another artist a while ago about being in New York City in the late seventies and early eighties, being on the Lower East Side. And he said to me that back then, we could afford to starve.

Matt: That's genius. That really is, and that's true of just everything. You listen to a guy like Don DeLillo, a brilliant writer who could afford an apartment for $ 50 and sit there to write without worrying about it. You can't do that now. I mean, my son and his fiancée make great money, but they can't afford a house. It's crazy. It's a function of where we are as a society, and it's sad. And we don't celebrate weirdos anymore like we used to. I think that's part of what's going on today with our current zeitgeist.

Lawrence: Only some weirdos seem to get celebrated.

Matt: Well, the wrong weirdos. It's a particular brand of weirdo. My wife and I were just in Europe, and we visited the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, which is beautiful. I mean, it's a block of concrete with a bunch of chairs in it. [The Dadaists] are the original weirdos, right? Where is that today? They came up with something on their own and were able to do it. They could afford to starve, as you say. Anyway, now I'm complaining.

Lawrence: You mentioned that you had a career and now play music for fun. Are you able to enjoy it more now? Is it freer of aspiration, allowing you to be more in the moment?

Matt: Well, sure, I mean, I'm not a kid anymore, so I think that you either get super weird as you get older or you get more comfortable or you just get more comfortable being super weird. I did the job. I had a career and a family. It is cool to sit back and look at that. And then this legacy is also kind of part of that. It's kind of like the family that I raised, and now I get to enjoy it. You know, there are the bullshit aspects of the music business, but it still comes back to the joy of collaborative art. That’s what really gets me to work with my songwriting partners and make something out of nothing. You get a blank sheet of paper, and there's nothing there. Putting something on it is fun, rewarding, and cool.

Yeah, it's not the same thing as it used to be in the sense that there was a little more—not desperation, but that you're going to do all you can do. It's kind of like the fine wine, if you will. There's something good about the raw keg, but there's also something about that wine that has really sat around for a while and has gotten complicated and complex, and there's a lot going on. I think I just appreciate that more. I'm not sure that's the best metaphor, but… You know, look, dude, we're still here and some of us didn't make it, so—amen.

If, when we started 10 or maybe even 15 years ago, when we started doing this again, had we shown up and played for nobody, then perhaps I wouldn't feel the same way. It wasn't like screaming crowds, but we were stunned by how happy people were to see us. Okay, so we're playing in Newcastle, and this kid comes up to me. He's probably in his twenties, and he started crying, and he said, "I just wanted to tell you that I’d listen to your music with my father. He died recently, but when we would get together, that’s one of the things we did together. He turned me onto your music, and I came to see you, and I really like what you guys are doing now." And of course I lost it. I mean, damn, when you hear stuff like that, it's just—how can you not want to do it? It's beautiful. It's really humbling, flattering, and rewarding. And that is an external thing, but it sure helps. It helps you get through whatever nonsense is associated with the business.

I don't really like this word, but I'll use it. We feel blessed. I'm not a religious person, but we feel lucky that we have been able to do things that people really appreciated and that we can continue to do. And yeah, there's not a million of them, and some of them are going by the wayside, as is true of everything. But we're digging it. We're happy. We look forward to making our next record. We're working on it now. We enjoy the puzzle, figuring out what palette to pull out and what the next color is, that kind of thing. So it's still rewarding, and we hope that other people enjoy it.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments