Ahoy, loyal reader! This is Michael, your host (formally known as your 'ghost host' IYKYK), guiding you down the trails and overgrown paths of this particular Zone we call the Talk Of The Tonearm newsletter. Unlike the Stalker's Zone, this newsletter is not a "maze of traps." Instead, it's a plethora of links and discovery. I couldn't be more excited for you to dig in, so away we go:

Surface Noise

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

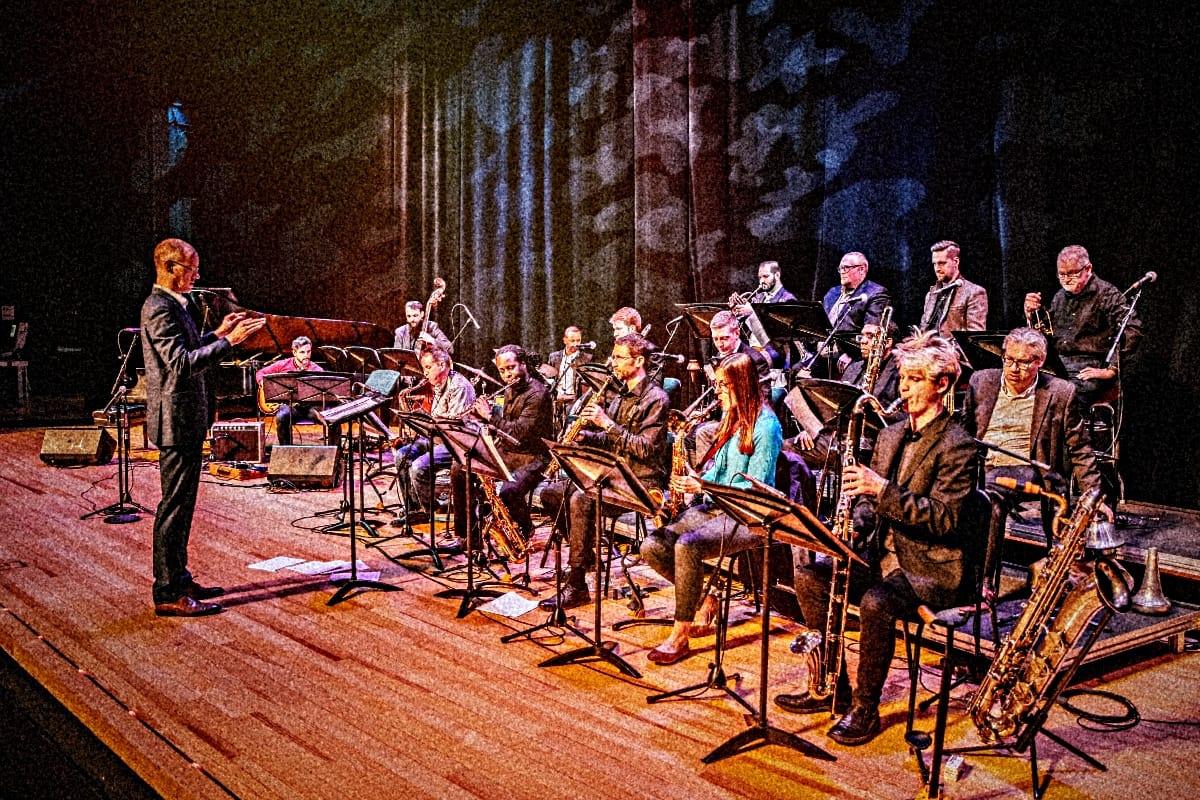

There's the usual narrative of American jazz: serious players move to New York, endure the struggle, and either make it or burn out trying. But saxophonist Sean Imboden left New York and a comfortable career path on Broadway to join the jazz community in Indianapolis. There, Imboden set up a thriving seventeen-piece ensemble and successfully crowdfunded his debut album, Communal Heart. His story signals the broader counter-migration reshaping American jazz as musicians abandon New York's oversaturated scene for cities where the competition isn't as fierce and the cost of living isn't as expensive.

Distance from jazz's institutional centers also brings aesthetic freedom. In our interview, Imboden admits his compositions are "fairly dissonant, kind of abstract, maybe a little more modern than what the traditional jazz listener wants"—but crucially, he doesn't care. Five hundred miles from the Village Vanguard, he can write what excites him rather than what might impress a fickle and often jaded cosmopolitan audience. Will moves like this inspire the return of distinct regional scenes, most recently found with indie rock in the '80s and hip hop in the '90s? Let me put my own cards on the table: I strongly believe that artists grow in much more interesting ways when they focus on a smaller local community as their primary audience.

But let's get back to the economics. Imboden's $20,000 Kickstarter goal would be laughable in most coastal cities, especially for recording and maintaining a seventeen-piece band. However, in Indianapolis: result! Imboden and musicians like him create mini-ecosystems where the venues are community anchors, crowdfunding replaces label support, and local audiences come along for the ride. The great jazz migration is reversing, and American music grows richer for it.

Playback: Daniel Fortin Finds New Voices on 'Cannon' → Daniel Fortin, a jazz bassist from Peterborough, Ontario, discusses how growing up in a smaller arts community gave him opportunities that he wouldn't have found in a larger city. He says that learning opportunities with seasoned musicians came to him because there weren't many jazz bass players in town. That's an important part of Fortin's story, which brings him to where he is today.

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

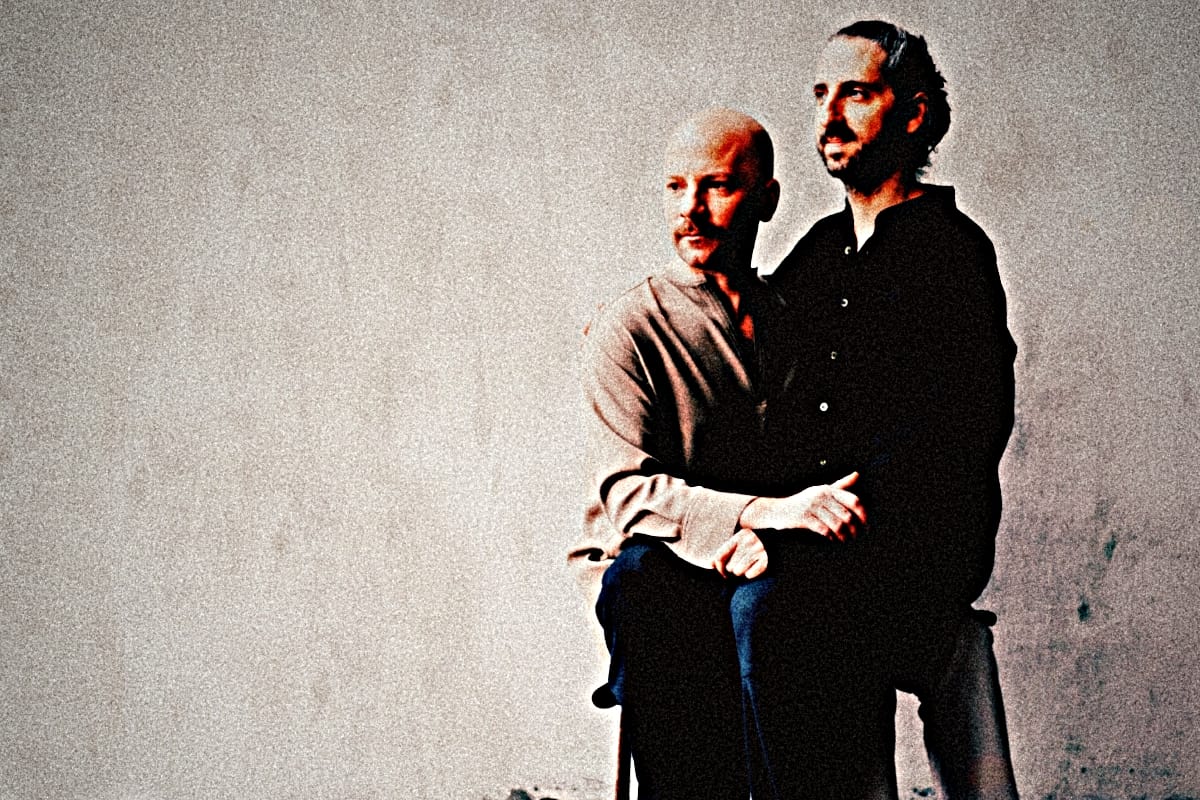

In their interview with The Tonearm, James Holden and Wacław Zimpel mention each studying with different members of the Guinia family—Holden with Mahmoud and his son Houssam, Zimpel with Mokhtar. Holden and Zimpel understand the spiritual implications of the Gnawa musical tradition, but it's easy to see how the Moroccan masters might need to adapt these ancient aspects across cultural lines. Samir LanGus of Innov Gnawa spoke of this process while describing work with British producer Bonobo: "He wanted us to change the lyrics because that song originally speaks of God and His Prophet... He plays his music in clubs and all of that, so [the original lyrics were] not appropriate, so we put different words." The essence remains intact, but the religious language gets stripped away, allowing sacred frequencies to slip past cultural customs.

This particular translation is more common than you might think; many Western artists have studied with various Guinia family members. Mahmoud alone worked with Bill Laswell, Pharoah Sanders, Carlos Santana, Peter Brötzmann, Floating Points, and, allegedly, Jimi Hendrix. Each received varying degrees of access to handed-down techniques intended to heal via trance states. You could say there's an invisible network of initiated Western musicians who carry Gnawa DNA in their work, often without audiences recognizing the source. Holden's feeling "liberated to try things I'd never tried before" and Zimpel's description of "turning off the analytical mind and just following the stream of music" suggest they're applying methods absorbed from their respective teachers.

We could consider the version of Gnawa healing that reaches London studios to be an authorized bootleg. The music maintains the essential spiritual operating system while removing elements that could be misunderstood or misappropriated. Holden and Zimpel's process of creating one track per day with "complete surrender to the moment" might even mirror traditional Gnawa healing ceremonies, the music unfolding organically according to spiritual need. Thus, the Guinias' tradition of musical healing reaches anyone who needs it, regardless of their relationship to the original religious framework.

Playback: Aho Ssan and Resina Learn to Disappear Completely → Aho Ssan and Resina describe surrendering their individuality to access deeper collaborative states, much like Holden and Zimpel's descriptions of turning off the analytical mind. Aho Ssan discusses explicitly how this process connects to navigating multiple layers of imposed identity as a Black artist in France, suggesting a parallel form of cultural translation.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

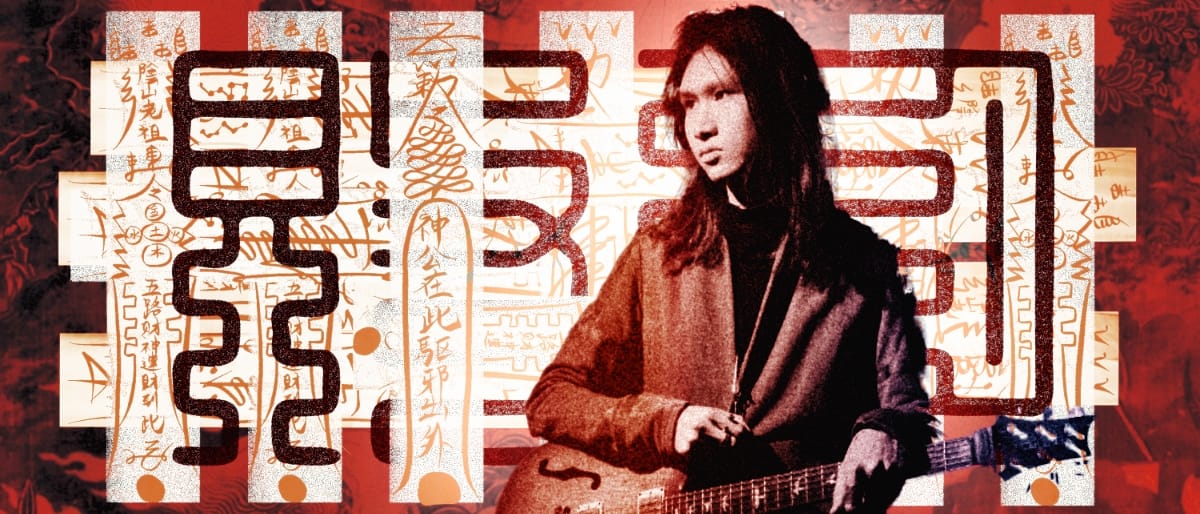

Here's another tale of handing down and translating a complicated musical tradition. Lingyuan Yang learned to use "generated numerical sequences" on his album Cursed Month by studying 'New Complexity' composer Brian Ferneyhough. These compositional methods are like a hermetic ritual, incorporating rhythmic values, pitch classes, and dynamic markings derived from interlocking numerical relationships that bypass conscious control. Yang adopted these techniques for pieces like "Ritual Fire," where drummer Asher Herzog navigates blast beats through rapidly shifting meters, ranging from 15/16 to 7/16 to 5/8. These complexities can access primal intensities by favoring something visceral and unconscious over rational composition, something Yang is aware of.

Again, we're quoting esoteric traditions, whether intentionally or not. Medieval masters, such as the French poet and composer Guillaume de Machaut, embedded sacred numbers into their masses, believing that mathematical ratios could invoke a divine presence. Renaissance theorists, such as Marsilio Ficino, treated composition as a form of magic, writing extensively about music's numerical connections to cosmic harmonies. The Enlightenment drove these ideas underground, but they resurged through figures like Iannis Xenakis—whom Yang cites as an influence—who used mathematical functions to generate his music. Yang's combination of Ferneyhough's systematic complexity with shamanic themes makes this connection even clearer. Cursed Month draws from Chinese zodiac fortune-telling, its title referring to those inauspicious months where people might "seek out shamans to try to change their fate." Mathematical composition becomes technological shamanism, algorithmic generation as modern divination.

Yang's quarter-tone guitar work introduces another hermetic dimension. His microtonal intervals create "friction" and "unease," rhyming with the acoustic tensions historically associated with supernatural power. Pythagoras believed specific ratios could induce altered consciousness, and Yang's non-tempered intervals remind me of similar psychoacoustic ambitions. His forthcoming work promises "Just Intonation tuning systems,” creating "almost otherworldly" harmonies—thus, the systematic calculation of ratios that produce transcendent effects. Is experimental music the modern grimoire?

Playback: Chicago's Sons of Ra Turn Jazz Into Heavy Weather → Sons of Ra's use of blast beats within carefully calculated odd meters (referencing Miles Davis and Tony Williams as "guiding principles") further demonstrates how complexity can bring about intensity. And the band's method of "arranging around drones" is their version of Yang's numerical sequences, providing compositional frameworks that bypass conscious control.

The TonearmAnthony David Vernon

The TonearmAnthony David Vernon

Anthony David Vernon's argument that hip-hop should embrace anti-fascist resistance hinges on a provocative concept: "rebellious loving." This phrase captures how hip-hop's political power extends far beyond simple opposition. Hip-hop, as a unifying culture, doesn't just resist through anger—it resists through a particular form of militant tenderness that fascism cannot comprehend or co-opt. If you look, you might find this paradox laid out in plain sight across modern hip-hop. One example is Kendrick Lamar delivering vulnerable insights over harsh sonic textures, like his voice cracking with rage on "The Blacker the Berry" while expressing the psychological baggage placed on so many Black men. The aggressive delivery doesn't mask the vulnerability. It amplifies it.

Vernon identifies this dynamic through Lil Darkie's question: "Why won't you choose to-to love everybody/Bitch, how many times are you gonna ignore the signs in people's rhymes?" The aggression serves the love, not the other way around. We can see hip-hop's harsh language as a form of accountability culture, spoken by artists who refuse to let their communities slide into complacency or self-destruction. Even the diss track, which appears to be pure destruction, often expresses community care. It's as if artists call each other out to maintain standards, with even the harshest critiques containing implicit respect. The message is that we care enough to fight for authenticity.

Fascism can't replicate or co-opt this dynamic because its ideology requires enemies to remain enemies. Hip-hop's tradition allows for adversaries to become collaborators and verbal violence to partially disguise mutual respect. Vernon suggests that hip-hop's weapon against fascism is "the mic, not to change the minds of fascists, but to convince the people to be blatantly against fascism." Perhaps the power runs deeper: hip-hop's practice of aggressive love offers the warmth of accountability and community care where fascism produces only the cold comfort of hatred.

Playback: Wayne Horvitz and the 'One Essential Arc' → Wayne Horvitz's emphasis on "creative friction" and collaborative dialogue echoes hip-hop's ability to turn conflict into community building. His method of pushing classical musicians into "uncharted waters" reminds me of the same militant tenderness that Vernon identifies—using confrontation as a tool for growth and connection.

The Hit Parade

- Martin Thompson's latest full-length as Bit Cloudy arrives with teeth bared and fists clenched. Over ten tracks of brooding electronic aggression, U.S. Nadir is an instrumental protest album and Thompson's sonic exorcism of his anxiety and frustration over America's political turbulence. Recorded swiftly in early 2025 from Thompson's East London living room, the album crackles with immediacy—anger and confusion crystallized into dissonant frequencies. However, U.S. Nadir proves less abrasive than its subject matter might suggest, though distortion, glitch, and fragmented beats indeed abound. Thompson allows brightness to pierce the electronic storm through synthesizer tones and guitar lines that resist relegating a nation's fate to utter hopelessness. The album also leans toward the '90s era of Aphex Twin-like digital excitement through its breakbeats and bass drones. "Troll, Grifter, Scammer, War Profiteer" is a title that perhaps sums up this project, though the track itself unfolds as slinky electronic dance music with disorienting sounds of protest (or anguish?) mixed beneath syncopated rhythms. "Bad Bad Faith, Bad Bad Actors" showcases Thompson's inventive sound-play through rhythmic handclaps that fade in and out with almost joyful abandon while the building blocks of cinematic tension increasingly crowd the stereo field. And “Discourse Inferno" wins the clever title award. Its death disco includes looped breakbeats and staccato synth sequences, as Blade Runner-esque lead lines zap over our similarly futuristic dystopia. Album standout "Stars & Bars Petrol Tank" features one of the set's most modern-sounding rhythm tracks, heaping tonal drama atop melodies that drone into distant reverb, perhaps imagining where this all ends up. It's a dark one, but Bit Cloudy's command of melody and artful treatments appeals beyond the necessity of like-minded political statements. (Check out an interview with Martin Thompson AKA Bit Cloudy on The Tonearm.)

- Toronto's Avi C. Engel is often associated with folk music, but their music exists somewhere else entirely. The evidence is in Mote, an album comprised of eight wanderings that exist within their own peculiar home turf. Built around voice and acoustic guitar yet embellished with the likes of haunting gudok lines, these compositions feel more like poetic meditations than mere songcraft. Engel's voice floats within the arrangements rather than accompanying them, and the occasional self-harmonizing, such as on the waltzing "Rip Van Winkle,” possesses an inherent magic that delights the eardrums. There's a solo intimacy to what Engel paints on Mote that's accented rather than interrupted by delicate layers. For example, the percussion stays non-existent or minimized, often just beats against the hollow guitar body. Anthéne's Brad Deschamps adds rising atmospherics to the mesmerizing "Ogre's Banquet," a sparkling display of patience and constraint that typifies the album's careful approach, and collaborators Tsinder Ash and Liz Dimo contribute clarinet and atmospheric guitar work. The additions dissolve seamlessly into Engel's vision. The album's visual representation—a nebula-like creature of Engel's own photographic manipulation—captures the dual nature of the organic and the otherworldly. Avi C. Engel possesses a rare ability to create mystery without pretense and songs that seem like small ceremonies, intimate yet universal in their quiet reach and moving portrayals. (Check out an interview with Avi C. Engel on The Tonearm.)

- Short Bits: Merlin CEO and Creative Leadership host Jeremy Sirota turned the tables on Spotlight On's Lawrence Peryer, putting him in the interview seat on the latest episode of the Spotlight On podcast. I think this is a must-listen: LP (and Jeremy, too) drop multiple wisdom bombs about creativity, the music industry, and making one's way through a professional career with an artist's mindset. • Thanks to the Enzian Theater, I finally experienced the awe of seeing Stalker on the big screen. That means it's time to revisit this excellent article on 'the weird history of the Soviet ANS synthesizer.' • An essay I posted to our Bluesky feed, which generated a lot of comments: How 80s bands toured in an unconnected world • Here's a gift link to a terrific article in the New York Times about the history of the ECM New Series. • I can't stop listening to the latest Midnight Radio mix, and I'm honored that my prompt inspired James to put it together.

A Shout from the 'Sky

Deep Cuts

Being among our featured artists this week, James Holden and Wacław Zimpel were asked this commonly perplexing question: What’s something you love that more people should know about?

James Holden:

Oh, this is hard. Can I have two? The musician Motion Sickness of Time Travel, who Gemma and I love—she has a really nice sensibility, witchy, magical, transcendent music, very real and place-y. And the concept of anarchism, because a lot of smart people have a wrongheaded idea of what that means, and they're missing out: there's nothing more beautiful and true than "we belong to no one; all we have is each other!”

Wacław Zimpel

Yeah, really hard one. I met young artist Tomin Perea-Chamblee a couple of weeks ago in New York, and he gave me his album A Willed and Conscious Balance, which I love! Also, the fact that Tomin is playing alto clarinet is even more special to me, because there are a handful of people playing this wonderful instrument. And another thing: The Penguin Book of Polish Short Stories—an anthology of short stories of great Polish writers translated into English. My favorite one is "The Isles" by Dorota Masłowska, which is part of her book Magical Wound.

Justified & Up-To-The-Minute

Talk Of The Tonearm is the newsletter you're looking for, appearing in your email inbox every Sunday sometime after 3 AM eternal.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Run-Out Groove

Folks, if you ever get the opportunity to see Stalker projected on a large screen, do not pass it up. Get there early, even if you have to stand in the sun for 15 minutes like we did, and grab the best seat in the house. What a thing that movie is. As Thomas, my uninitiated friend who I convinced to join me, said: Wowzers.

Thanks for making it to the end of this week's Talk Of The Tonearm newsletter. I'm so happy you could join us on this lazy Sunday. Here's the thing: you probably have a friend who enjoys this kind of stuff, this wild music, these references to Soviet philosophical sci-fi from the late '70s, and so on—please forward the newsletter to them. I bet they'd like it. You can also share the 'View in browser' link at the top on your social media maelstrom to even greater appreciation. Let me hear from you, too. Just reply to this email or contact me here. I read it all and respond as well, unless your name is Quentin, in which case I'll likely ignore you (long story).

Have a wonderful tail end of your weekend. Maybe make a tasty dinner for your friends and loved ones. I've found that to be an enjoyable Sunday thing to do. It sets a good tone for the week ahead, which, no doubt, will once again prove challenging. I know we can make it through, and next week we shall meet again. I'll see you then! 🚀

Comments