As New England Conservatory prepares to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Gunther Schuller's birth on November 22, three musicians who knew him in different capacities, including his son George Schuller, former Contemporary Musical Arts Chair and Department Advisor Hankus Netsky, and Jazz Studies chair Ken Schaphorst, reflect on the composer, educator, and visionary who transformed American music education.

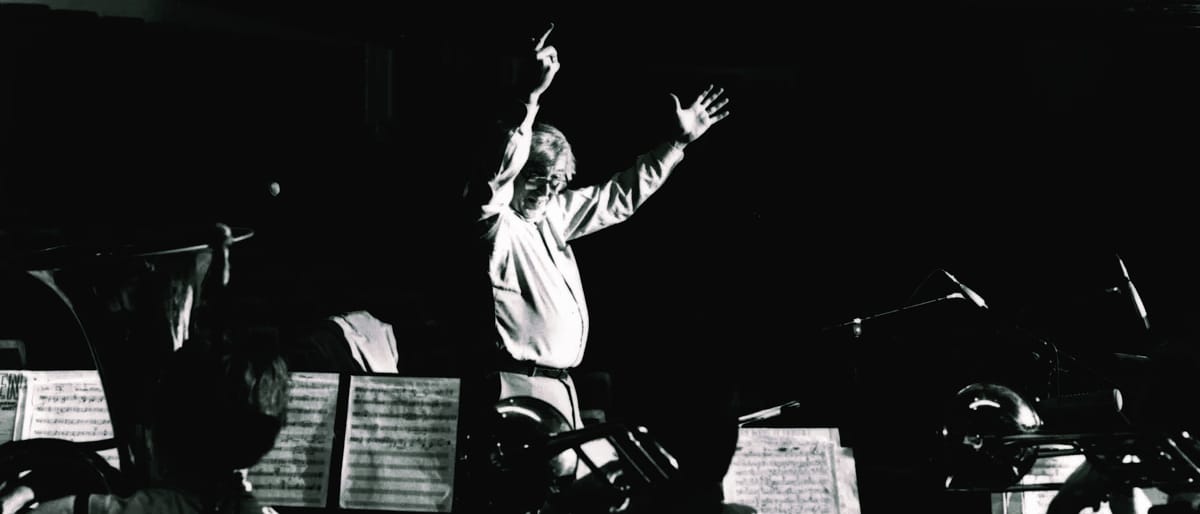

Gunther Schuller became president of New England Conservatory in 1967. Within months, he established the first fully accredited jazz studies program at an American conservatory, enshrining the music he called "Third Stream" (that is, music combining classical and jazz techniques) into mainstream music academia. The MacArthur Fellow, Pulitzer Prize winner, composer, conductor, and French horn player who had recorded with Miles Davis at 24, believed conservatory training needed to include music from everywhere, not just Europe.

This polyglot belief manifested in Schuller's faculty recruiting. The Contemporary Musical Arts program at NEC now includes musicians from Central Asia, the Middle East, China, and Haiti. Jazz students study European harmony and global improvisational practices. Faculty positions go to working artists making new music. Teaching klezmer next to Bach seemed radical in 1967. Now it describes how the school functions.

November 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of Schuller's birth. George Schuller, a drummer and bandleader who graduated from NEC in 1982, grew up as Gunther's son in a house where music played constantly and nobody worried about categories. Ken Schaphorst chairs the Jazz Studies department Schuller founded and reflects on what it meant for an established classical musician to give jazz institutional legitimacy when most conservatories dismissed it as entertainment. Hankus Netsky, Former Chair and Department Advisor of Contemporary Musical Arts, recalls how Schuller supported his research into Eastern European Jewish music when other institutions pretended those traditions didn't exist. They discuss work ethic, institutional memory, and who decides which music matters.

Lawrence Peryer: George, growing up as the son of such an influential figure, how did you experience the difference between Gunther Schuller, the public innovator, and your father at home? Did his musical philosophies extend to his approach to family life?

George Schuller: I believe we had a fairly normal family life—nothing too hectic, not a lot of drama, moved once (New York to Boston), and spent one year in Berlin during the mid-1960s. We allowed time to do a fair amount of family things, like the occasional ski trip to Vermont, brought back living conch shells from the Bahamas, crossed through Checkpoint Charlie to visit our East German relatives, sang carols on Christmas Eve with our Newton Centre neighbors, and packed the family station wagon full to spend every summer at Tanglewood for two decades. And obviously, music happened to be the predominant backdrop for almost every waking hour.

In hindsight, home probably felt more normal than one would think—either that or I didn't know better. For sure, Gunther led a busy life, traveled much, and was often consumed by his role as a kind of multifaceted ambassador to all things music and the arts. But I somehow may have taken all of that for granted and went about my daily teen activities as if nothing was out of place. Of course, my mother kept things quietly tethered, safe and sound.

The fact that family life was intertwined with Gunther's mode of operation was perhaps emblematic of the plurality and democratic values he instilled in my brother and me. He always championed and consistently advocated for the unheralded musician while battling certain conglomerates of the industrial music complex, which I won't get into here.

Lawrence: That work ethic seems to have been foundational. How did it influence your own path as a musician?

George: Growing up in that environment may have subconsciously prepared me for a life in music. But if it wasn't music per se, then I suppose it would've been some other creative mode of interest. As a result, there were many paths to choose from. I was just happy to settle on a few of them while a life in jazz emerged as my primary avenue.

I think it was his work ethic that influenced me the most, which was unmatched and kind of crazy. My mother was super supportive and mostly tolerant of that ethic (and the pace of it all), while at times it did challenge the homestead, but we all somehow lived to tell the tale.

Lawrence: Ken, when Schuller established the first fully accredited jazz studies program at a conservatory in 1967, what resistance did he face, and how did he convince the classical establishment that jazz belonged in formal music education?

Ken Schaphorst: By 1967, Schuller had established himself as an eminent classical performer, conductor, and composer. He was also extremely passionate and articulate in making his case for jazz's artistic and cultural relevance. It was his status within the classical community and the force of his personality and perspective that won over the establishment.

Lawrence: Many composers have attempted to blend jazz and classical music, but Schuller's Third Stream concept went deeper than simple fusion. What made it fundamentally different?

Ken: It was the depth of Schuller's knowledge and love of both jazz and classical traditions that made his fusion unique. His working relationship with jazz artists such as Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, and Charles Mingus gave him credibility and insight into that music. And he grew up in the classical world. There has always been a tendency in music education to focus on one style or tradition. But Schuller felt strongly that students should be free to develop their own artistic vision and to explore multiple musical traditions, just as he did himself.

Hankus Netsky: You can't really look at a genre like klezmer without looking across all sorts of musical and geographical boundaries. There are the boundaries within the worlds of Eastern European Jewish musical culture—liturgical traditions, Hasidic music, Yiddish folk song, Jewish art music, and the music of the Yiddish theatre. Then you also need to consider the larger cultural context of Eastern Europe and, later, in the U.S., the world of maqam that influences klezmer's modal language, as well as Ukrainian, Romanian, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, and Roma influences, and the overall social context of music in Jewish society.

It's really intrinsically parallel to the hybrid cultures that Schuller foregrounded. For example, you can't look at ragtime pieces without also considering the influence of military marches on their form and harmonic structures, and you can't look at the development of Black improvisational musics without also considering the worlds of African rhythms combined with the structures of European harmony.

Lawrence: Hankus, you mentioned that both Gunther and Ran Blake encouraged you to go deeply into Eastern European Jewish music. How did Schuller's vision influence your mindset to preserving and reimagining those traditions?

Hankus: As for reimagining, most of the models for that have come from musicians with extensive knowledge of performance practices outside the Jewish community, most prominently from Black improvisational musical genres from which we and our predecessors took their inspiration—klezmer swing, klezmer ragtime, klezmer ‘free jazz,’ and so on—but also from other genres, including bluegrass and rock. Both Gunther and Ran Blake encouraged me to go deeply into the traditions of Eastern European Jewish music. Gunther saw parallels within the resurgence of these traditions in his own work and definitely became a fan. Ran Blake, the founding chair of our program, actually incorporated klezmer and Yiddish repertoire into his own work and created some of the most interesting reimaginings within the genre.

Lawrence: To what extent do you see your work as preserving versus expanding klezmer music?

Hankus: I think that my creative work is much less informed by preservation than it is by the kind of innovation that is intrinsic to the music itself. I listen to early klezmer recordings and hear the musicians exploring every groove and style that comes their way—ragtime, tango, foxtrot, bolero, Latin, swing, bebop, and so on. The genre only seems to turn inward on itself once it's cut off from the vibrant culture that created it. It's my goal to make sure that it stays vibrant by embracing the culture of the living musicians who are seeking to innovate within it, that it constantly absorbs from the vibrant musical cultures that surround it, rather than attempting to become some sort of period-based museum piece.

In terms of preservation, my work in reviving Dave Tarras's legacy and creating a comprehensive archive of Eastern European Jewish music is all focused on documenting a world that once existed, but I'm not necessarily aiming to recreate it exactly as it was. However, I do feel a responsibility to accurately represent the stylistic languages of this music, in much the same way that someone who may improvise over chord changes to a standard understands the underlying stylistics and structures of that language. My goal is to engage the tradition, but take it somewhere new.

Lawrence: Ken, you mentioned Schuller as "the ultimate musical polyglot." Can you walk us through a specific example of how he facilitated collaboration between musicians from different traditions who had never worked together before?

Ken: In 1957, Schuller organized the Brandeis Festival for the Arts around the theme of Third Stream Music. He commissioned three classical composers, including Milton Babbitt, Harold Shapero, and Schuller himself. He also commissioned three jazz composers: Jimmy Giuffre, Charles Mingus, and George Russell. Several of those commissioned pieces are now considered landmarks, including Russell's "All About Rosie," which will be performed by Fred Hersch and the NEC Jazz Orchestra on November 20.

Lawrence: As someone who now leads the department Schuller founded, what specific teaching methodologies or philosophical ideas of his do you still employ?

Ken: One of the things that stood out in Schuller's vision of a Jazz Studies Department was his interest in hiring artists who were actively involved in creating innovative music. This approach continues to this day, with many of the most prominent jazz artists teaching at NEC, including Donny McCaslin, Jason Moran, and Nasheet Waits. Students are motivated when they are surrounded by artists doing the kind of work that they aspire to themselves.

Hankus: Gunther's vision of creating "the complete musician" still permeates the department. We still insist that our students hone their aural skills to a very high level, acquire a diverse repertoire, explore the process of channeling their creative imagination, look at their own life's journey, open themselves to diverse global influences, get out of their comfort zones, acquire traditional European musicological and theoretical skills, and emerge as unique composers, performers, and improvisers. What has changed are some of the tools we use. For example, founding chair Ran Blake's book, The Primacy of the Ear, has become an essential guide for teaching our students about musical creativity, and NEC has sought out our faculty to teach students to master contemporary production techniques and to compose using Digital Audio Workstations.

Lawrence: How did Schuller's philosophy address the gap between formal education and the practical demands of professional music-making?

Hankus: Schuller was very critical of traditional conservatories. He couldn't fathom why they kept their pedagogy limited to the world of European concert music, while so much music of great artistic merit was being created outside it. I still feel strongly that the pedagogy we've developed using his philosophy needs to be foundational to training contemporary musicians, and I hope NEC will embrace more of that philosophy in training all of their students in the future. The education I received at NEC in the 1970s prepared me for everything I've encountered in my musical career over the past 47 years. Focusing only on European repertoire would have only prepared me for some sort of nineteenth-century career as a European concert musician. Heaven help musicians trying to sustain careers like that in the twenty-first century.

Ken: Schuller always encouraged creative artists to be true to themselves. Given the varied music young musicians are exposed to today through the internet and social media, that broad range inevitably manifests in their work. It would be disingenuous for students to reject part of their own experience.

Lawrence: George, you've worked with many musicians who knew your father professionally. How did they describe his working or collaborative style?

George: He was known as a force of nature—unrelenting in some ways, with high expectations for the work that needed to be accomplished. But I think they all knew that and welcomed his passion and work ethic. At the same time, he was thoughtful, compassionate, and understanding of the parameters and level of talent he was working with. Yet, he found ways to pull everybody's creative chain to another level when required.

Not sure if this answers your question, but I think the fact that he was instinctually a multitasker, music and otherwise—that was something I probably noticed and later took to heart. It most likely became the template for my own career as a musician, bandleader, composer, arranger, producer, archivist, and so on. But I'll add that not many could keep up with Gunther's kind of pace for what he achieved in his lifetime.

Lawrence: Looking at the musical landscape today—the genre-blending, the global influences, the breakdown of traditional categories—how much of what we take for granted can be traced back to the groundwork your father laid?

George: Actually, it really started in earnest in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He was a lone island at first, surrounded by his classical freelancers and Met Opera colleagues. Eventually, he found like-minded, forward-thinking musicians, especially on the jazz side, who were coming to terms with the advances of certain twentieth-century compositional practices. It reinforced his belief that there was a pathway to bringing the two streams together.

As exciting as those heady 1950s were, most of those experiments may have fallen short of their appointed goals and caused a bit of controversy among the stodgy traditionalists and critics alike, but gained ground slowly so that by the 1990s, it exploded into all sorts of directions (aka ‘world music’ and the like). But it would be naïve to think that he alone was responsible. There were other forces at work, marinating and subtly percolating throughout the first half of the twentieth century, that laid some of the groundwork for the eventual détente of disparate musical minds.

Lawrence: What specific elements of Schuller's approach do you most want current students to understand and carry forward?

Hankus: All of them. The concert we're producing at NEC on November 18, honoring Ran Blake's ninetieth birthday and Gunther Schuller's centennial, will feature two compositions based on Gunther's "Magic Tone Row." A piece that I arranged features a native Yiddish speaker from our department and requires the instrumental soloists to be fluent in traditional Jewish cantorial improvisation. Another one contrasts the percussion background of virtuosic soloists drawing on Chinese, Haitian, and Persian rhythmic traditions. There's an original Americana song, a well-known Haitian song, students channeling the innovative musical languages of Ornette Coleman (really a Schuller discovery) and NEC graduate Cecil Taylor. There are selections that originated with Jelly Roll Morton, Charles Ives, Billie Holiday, and Sweet Honey in the Rock, and our emeritus chair, Ran Blake, who turned 90 this past year, a reimagining of a piece originally composed by twelfth-century German composer Hildegarde Von Bingen, in addition to selections that reach across and innovate within multiple traditional genres. I'm pretty sure that it's just as Gunther would have wanted it.

Lawrence: George, is there one specific memory of your father that captures something essential about his outlook on music or life that shaped who you became?

George: I think it was his work ethic that influenced me the most, which was unmatched and kind of crazy. My mother was super supportive and mostly tolerant of that ethic (and the pace of it all), while at times it did challenge the homestead, but we all somehow lived to tell the tale. And to this day and beyond, let's honor his tremendous creative output by giving him one huge musical hug as he turns 100. Happy birthday, Dad.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments