Some artists spend years chasing the perfect collaboration. Christine Ott and Mathieu Gabry discovered theirs through toy instruments and a meeting that almost didn't happen. But what came from that encounter was Snowdrops, a duo whose approach to sound is at once ancient and futuristic, rooted in improvisation and meticulously crafted.

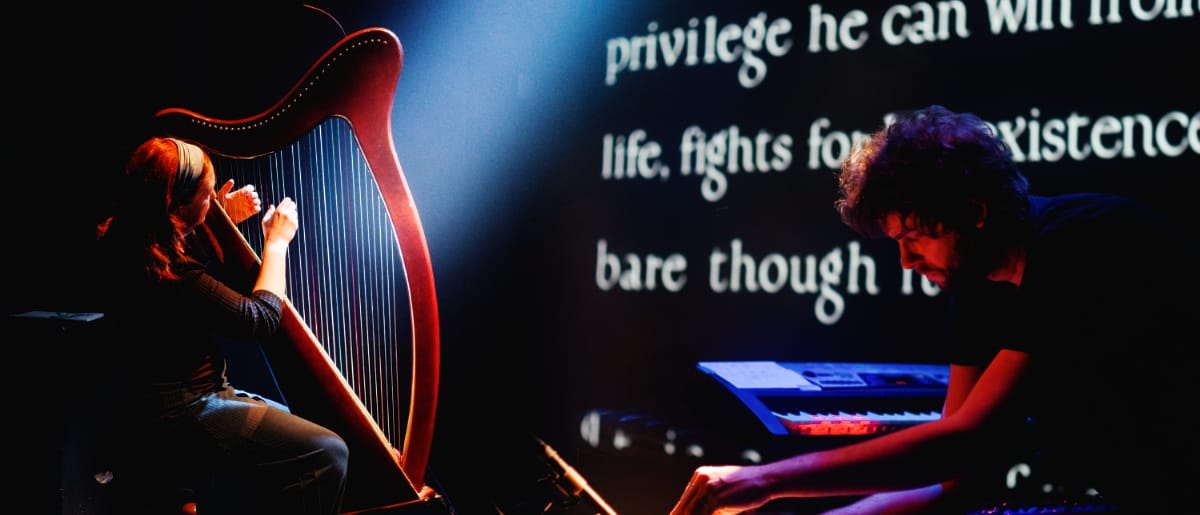

Their latest release, ARAN, completes an ambitious trilogy of live film scores for Robert Flaherty's documentaries, following previous treatments of Nanook of the North and TABU. Recorded in a single take at the intimate Cheval Blanc venue just outside Strasbourg, the album captures Ott and Gabry responding to Flaherty's 1934 portrait of Irish fishing families with an hour-plus score that moves between chamber post-rock, impressionistic piano, and otherworldly electronics. Ott taught herself harp specifically for this project, adding it to her arsenal of piano, ondes Martenot, and theremin. Gabry contributes keyboards and his self-built "drone box," allowing for atmospheric foundations that complement Ott's melodic explorations.

What distinguishes this final installment in their Flaherty trilogy is how Ott and Gabry translate specific visual moments into musical gestures without falling into mimicry or camp. Their score for the young fisherman's precise casting in "The Fishing Line" becomes a series of repetitive loops and harp glissandos, while the hallucinatory shark hunt in "Beneath the Surface" calls forth theremin sounds that echo animal cries. These aren't literal translations but emotional equivalents. It is music that captures the essence of human courage against elemental forces that runs through all of Flaherty's work.

Lawrence Peryer: The two of you formed Snowdrops in 2015 after meeting during a rehearsal session where Christine brought a toy piano and a hand-pumped organ. There's something beautifully unpretentious about that origin story.

Mathieu Gabry: Yes, you're well informed! And yes, perhaps nicely unpretentious, but that's the truth! (laughs) Joking aside, it may be reassuring to think that in today's music world, you don't have to be pretentious to exist.

In any case, yes, that's how we met. I had a band, and Christine came along with these two instruments to try things out. I didn't know her at all; I had no idea about her work or her incredible career as a musician. Perhaps if I had known, I would have been intimidated, and the encounter would never have happened. No, it was just as good that way, and we immediately connected through music and improvisation together.

Christine Ott: The craziest thing is that I almost declined the invitation to this rehearsal.

Lawrence: Christine, you've said that your fascination with the ondes Martenot began visually, with your being drawn to Jean-Marc Morin's "Son-Relief" score before you were enchanted by its sound possibilities. That suggests a synesthetic approach to music-making. How do you think about the relationship between what you see and what you hear when you're composing?

Christine: Yes, it may seem surprising, but I feel that sight and vision are senses that sometimes precede the perception of sound. In this case, Jean-Marc Morin's score had a very distinctive contemporary style, like a true pictorial work that caught my attention and curiosity.

And it's surprising that you mention synesthesia, since Maurice and Ginette Martenot reacted this way, associating sound and color, but that's not the case for me. At the origin of the composition, there is always a sensory and spontaneous musical gesture, and improvisation arises from this intimate, inner feeling in response to the image. It's a bit like baring oneself.’

Lawrence: What drove your decision to learn the harp for this project, and how does its voice interact with the otherworldly qualities of the ondes Martenot?

Christine: The harp is an instrument that fascinates me, terribly complex to play. I had the opportunity to get up close and personal with one during my Music and Cinema workshops, where, during a break, I was finally able to lay my fingers on one. I improvised for the first time, and in the end, a melody came to me, and the piece, "Chasing Harp," found its place on my album Time To Die.

Several months later, something wonderful happened. I went to see one of my best friends, a designer and stylist who had a magnificent harp in her studio. She offered to lend it to me. It was one month before the premiere of ARAN. I took the plunge and very quickly felt which scenes would be suitable for the harp, and those were precisely the scenes where the composition for the film was missing. It was the missing link.

So it would be wrong to talk about learning the harp, as I didn't really have time to learn and practice as I had done for years with the piano and the ondes Martenot. At the premiere, Anne, the harp teacher at the conservatory, was there, and even though she's a friend, I was petrified and afraid of her reaction. But she was wonderful, even though I'm one of the few people who play it left-handed. Once again, my approach to this instrument was sensory and instinctive.

Lawrence: Mathieu, lighting design during the day, musician at night—that's a unique combination of working with ‘light matter’ and ‘sound matter,’ as you've described it. How does your understanding of visual atmosphere inform the way you approach sound design and musical texture?

Mathieu: This is a presentation of myself that may be a bit outdated now, but I've indeed worked in the world of architecture and lighting design. There are some connections between the world of light and our work with Snowdrops, especially when we manipulate different forms of waves, as in the piece "Ligne de Mica" from our last album. But for ARAN, the main connection is more about working on narrative, experience, and dramaturgy. These elements can be found in both scenography and music, particularly in a long piece like ARAN.

I worked for several years in architect Jean Nouvel's lighting design department, and it was quite fascinating to see how his architecture also developed a strong and sensitive sensory experience. It's a bit the same with music, except that the experience is more direct and linear, as we follow the thread of time. But in the case of ARAN, it's still interesting to offer different listening experiences, independently by track, for the entire hour and a quarter, or with the film as a palimpsest.

Lawrence: When you first encountered Robert Flaherty's work, what was there about his visual language or approach to documenting human resilience that made you each think, "I need to create music for this"?

Christine: I was first mesmerized by the use of light and shadow contrasts. Some shots are reminiscent of real paintings. I was also captivated by the editing, which is musical, very rhythmic, and innovative for its time—I think—and for this type of documentary. What attracted me most, and what I find in all three films, is the humanity of the characters he chooses, who are always extremely endearing, human, and whole, in a way, without compromise. The way he films them makes us feel close to them; he creates an intimacy with us. There’s also a close relationship with nature, the sea, or the far north, with the characters always showing incredible courage in facing the raging elements—the storm, but also their destiny—as in TABU, revealing incredible resources. It's a beautiful life lesson for us.

Mathieu: Originally, we imagined this creation as a solo piano piece by Christine. I remember the first stage of creation very well. It was in February 2020, shortly before the world came to a standstill—as we know. We were giving a few performances of Nanook of the North in the large auditorium of the Château des Rohan in Saverne, in Alsace. We had a long break between the two performances. Rather than going out for some fresh air, I had the DVD of ARAN with me and started playing it. Immersed in the big screen and by the waves and lights, she began to improvise naturally on a beautiful Steinway. That was the first step.

Lawrence: Mathieu, tell me about the "half-composed and half-improvised" approach in this work. That's a fascinating balance to strike, especially when creating film scores. How do you maintain spontaneity while serving the narrative demands of Flaherty's imagery?

Mathieu: There are several things about that. Christine and I work by recording live to the image, improvising a lot. So these recordings are the first drafts, the first strokes of pencil, if I can say so. Then we think about it, choose, compare it to the image and refine it, and finally Christine and I ‘compose’ the music.

We arrive at a fairly precise composition, but nothing is completely set in stone. And it's not just a film score; it's a live soundtrack. So often we have to adapt, Christine sometimes has to adjust certain piano motifs to (re)find the synchronicity with the image, and I sometimes have to adjust certain textures on the keyboards depending on where we are playing. Basically, we have a rough outline of our composition, but we have to be even more attentive to each other, the film, the venue, and the audience to convey the original idea, even if it means deviating from the composition. It's sometimes like walking a tightrope.

Christine: I think Mathieu has said it all.

Mathieu: Oh, there's probably a lot more to say! I'm also thinking of certain compositions we have, which exist, have a style of their own, but are often difficult to write down. Often, they come from improvised gestures, which makes them a little more complex to write down and interpret, especially rhythmically. These are not mathematically written, calibrated pieces, but that is often what makes them more human and beautiful in our eyes. I am thinking, for example, of certain pieces for ondes Martenot and piano, a whole repertoire that we owe it to ourselves to write down. "Serpentine," for example.

Lawrence: How do you decide which visual elements deserve a kind of direct musical translation, such as the glissandos and loops in "The Fishing Line,” versus which ones need more abstract treatment?

Christine: It's just instinctive. You do raise a delicate point about setting a film to music, namely, avoiding the pitfall of mimicking or emphasizing what is already in the image. I think it's all a question of balance and finding the right delicate equilibrium between image and music, and I believe that it's up to the music not to weigh the film down. I find that the harp, with its soaring notes, creates space, while Mathieu sets the rhythm for the scene.

Mathieu: "The Fishing Line" is a special piece in ARAN. It's truly a unique scene, a moment in the film that stands apart, somewhat reminiscent of Nanook of the North. The son of the family stands atop the cliffs of ARAN, playfully casting his fishing line with great precision to catch fish. We really wanted to highlight this, especially since it comes after the first third of the film, and it brings a different orchestral feel. Orchestral yet clever. I play on a children's keyboard, whose keys light up when pressed, which I found second-hand for €8. I really like that, reminding me that you don't have to spend a fortune to record some beautiful things. And that fits in perfectly with this scene.

Lawrence: The theremin appears in "Beneath the Surface" during a hallucinatory shark-hunting scene. As a ‘distant cousin’ of the ondes Martenot, how does it extend the electronic vocabulary of this project without simply doubling what the ondes already provides?

Christine: My theremin also has a crazy history. It was a gift from someone unknown at first, a long story . . . too long to tell here. I also play it, without pretension, very humbly, with an unorthodox technique, totally influenced by my playing on the ondes Martenot. I love this incredible way of playing it. It's an instrument of space, and playing it standing up gives me freedom, the freedom to dance in space. But also, for this somewhat brutal scene, the theremin produced sounds that resembled the cries of the animal, the shark hunted by men.

Mathieu: Yes, it's definitely a piece that makes perfect sense on stage, accompanied by the film.

Lawrence: You recorded this at Cheval Blanc in Schiltigheim, the final rehearsal before the premiere, captured in the silence before the audience enters. There's something almost ritualistic about that. Can you talk about the importance of the recording environment's intimacy in capturing the music you wanted?

Christine: Yes, it was a great opportunity to record at one of my favorite venues, Le Cheval Blanc, a lively, intimate, and welcoming concert hall that has supported me in my projects for many years. It was a magical, suspended moment, timeless, completely immersed in the film, and in this utmost intimacy. Thanks to Benoît Burger, my favorite sound engineer, for this ‘live’ recording. So yes, that's what this album is all about. Being in the moment, immersed in the film's intensity, and conveying to the listener the emotion and extreme intimacy felt while watching it. It's a moment of intense sharing.

Mathieu: Yeah, "ritualistic" is a good term, it's really true—this venue is inspiring, a bit magical. We have a very deep story and connection with this place. We had reached the end of a long creative process with ARAN over four years, followed by a fairly long period of fixing and rehearsing this music. So it was a real performance to play this music, to play it in one go. Christine has some quite virtuoso piano parts, particularly in terms of synchronicity with the images (even if you can't see that on the disc). The disc is really a faithful, unadulterated reproduction of that hour and a quarter of music, with its moments of fragility and moments of truth. Like all our concerts, I hope it's always the same and a little different.

Lawrence: ARAN concludes this Flaherty trilogy, but it’s also part of your larger exploration of "ciné-concerts." How has creating live film scores changed your understanding of the relationship between sound and image?

Mathieu: I don't know if my understanding has changed. But in film concerts, we experiment with things and confront them with reality by being on stage. There's something I find quite beautiful about ARAN, which is that we've managed—I think—to offer something quite orchestral with minimal resources, with a little ingenuity, without tapes or artificial things. Everything is played live.

Christine: Perhaps by focusing on the essentials? Also in the orchestration and musical arrangement.

Lawrence: Both of you work across multiple projects: Christine with your solo albums and teaching, Mathieu with Theodore Wild Ride and other collaborations. How do you know when a musical idea belongs to your work together versus your other outlets?

Mathieu: Actually, it's not always easy! (laughs) There is indeed a great deal of overlap between our various projects, whether within our ensemble Snowdrops, or The Cry, or TWR. And I often participate in the production of Christine's albums, either as a kind of producer or simply as an outside observer. When putting together albums or soundtracks, some tracks often get left by the wayside. And sometimes they end up in other forms or in different projects. But we don't mind, the main thing is to get this music out there in the best way we can. To give you a few examples, I'm thinking of "Horizons Fauves," which we initially thought would be on a Snowdrops album, but that finally appears on Christine's Time to Die. Or "Burning Forest," an unreleased Snowdrops track reworked by Christine with Mondkopf and Frederic D Oberland to become "Burning." On The Cry's latest EP, released last month, we play around with this thing, crossing projects . . . We love this idea of a constellation of projects and bands around us.

Lawrence: Do you see these film projects as chapters in a larger artistic statement about humanity's relationship with nature?

Christine: I believe that these are projects that feed off each other and enrich us in different and complementary ways.

Mathieu: Yes, there is definitely that line in our work, whether it's on record, on stage, or in film scores. Well spotted!

Check out more like this:

The TonearmPeter Thomas Webb

The TonearmPeter Thomas Webb

The TonearmWilliam Slyter

The TonearmWilliam Slyter

Comments