The creative music world has long operated on traditional mentor-protégé relationships, where knowledge flows in one direction from established figures to newcomers. But what happens when two accomplished artists decide that model needs rebuilding from the ground up? That question sparked the creation of Mutual Mentorship for Musicians (M³), an organization that has commissioned ninety-two artists to create forty-six new collaborative works in just five years.

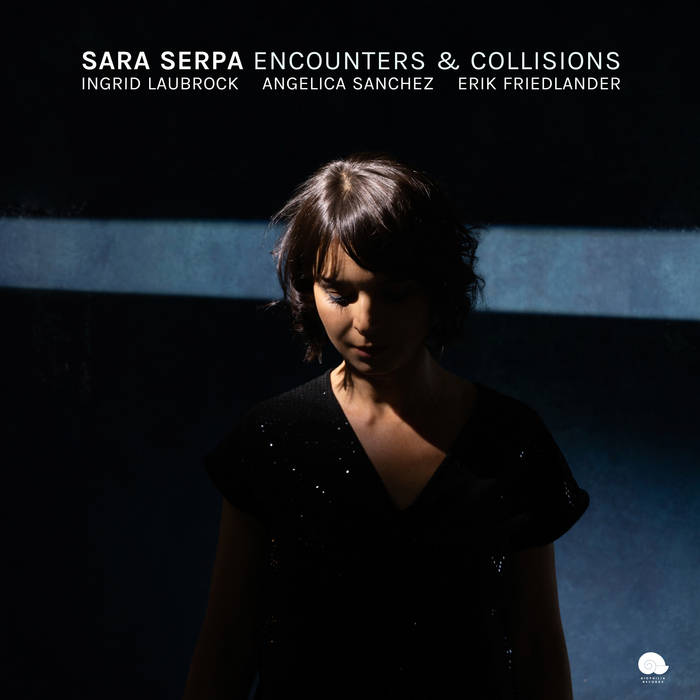

Sara Serpa and Jen Shyu founded M³ during the pandemic lockdown, drawing on their own experiences as women navigating the creative music scene, where they often found themselves the sole female voice in bands and venues. Serpa, a Portuguese vocalist and composer, brings her ethereal sound and background in social work to the organization's structural approach. Shyu, a multilingual performer whose theatrical works incorporate everything from teenage diary entries to East Timorese folk songs, contributes her research into traditional music forms and her Rome Prize–winning artistry.

Their conversation revealed the mechanics behind building an alternative to industry hierarchies. The pairing of artists for co-compositions, the launch of M³ Magazine with its focus on underrepresented contributors, this year's M³ Festival on October 4 at Brooklyn's Roulette Intermedium (featuring Grammy-nominated Becca Stevens and NEA Jazz Master Kenny Barron)—each choice dismantles something while constructing something else. Both artists spoke about teaching as a creative practice, vulnerability as improvisational necessity, and a model where support moves in multiple directions instead of following established power lines.

Lawrence: You both work extensively in what gets called "experimental" or "creative" music. How do you think about accessibility? Do you think about the listener in terms of making challenging work that still connects with audiences?

Sara: I follow what moves me in music and art in general, letting my curiosity guide me. I'm drawn to narratives, and even in the most "experimental" work, I like to imagine a logical sequence. At the same time, I know I can't control how people listen; either they connect with it or they don't. Of course, I love performing for a full room, and I'm inspired by the young generation of musicians I meet in workshops, programs, and universities who share the same passion and curiosity for this music and who are bringing new approaches and perspectives to the scene.

Jen: I would say that transformation is the first thing I think about, and accessibility, the last. This reminds me of sage advice that the late Von Freeman gave me years ago, before he passed: "You have the answer. Learn to translate it." I first go for creating the music that I want to hear and bring into the world that doesn't yet exist, but that honors and is deeply influenced by the things I love and am moved by. I want to reflect and critique what is happening in the world from a personal and an ancestral point of view. I want to sing taboos out loud and bring hidden histories or whispered things into the spotlight (i.e., environmental change affecting our fertility, or narratives of Chinese laborers in Cuba, or narratives of East Timorese women who survived a genocide which wiped out a third of their population). I'm always seeking that new combination of traditions, vibrations, and rhythms that best express what I'm hearing and the intention that I'm setting in my music; there are untold stories and people, especially women and nonbinary people, before thinking about accessibility.

Lawrence: Could you each tell me about how the spontaneous nature of improvisation interacts with the more structured aspects of your pre-composed work, particularly when dealing with personal subject matter? The word "vulnerable" keeps coming up for me.

Sara: For me, the structure gives a frame to hold the emotion, while improvisation allows the unexpected to surface. When the subject matter is personal, that openness can feel very vulnerable—but it's also what makes the music alive and honest.

Jen: I love creating both solely improvised and solely pre-composed music, but my happy place is mixing the two in a seamless way. I try to allow for both extremes to exist as there is so much beauty to organized vibration and time that is known beforehand, and then beauty to that organized vibration and time that is discovered through time. I try to be vulnerable in both extremes and everything in between—to play the music that is pre-composed as if I were improvising it, and vice versa, playing the unknown as if it was known. I love acting improvisation in that way as well and watching the stories unravel. You can only be a great improviser by being both as receptive as possible and willing to "yes and . . ." while also having encyclopedic knowledge and references. That's why this music is infinite.

Lawrence Peryer: Jen, your work often incorporates your own teenage diary entries and deeply personal family history. What's your process for deciding which private experiences are meant to become public art?

Jen: Yes, my work has become more and more personal as time goes on, which really began after my two years living in Indonesia. At first, I was solely exploring my East Timorese and Taiwanese ancestry and researching it through an esoteric lens and manifesting my experiments in my music. But I realized from living in and researching for extended periods of time in Asia, letting go of concerns of career really, and simply living in and serving the communities where I stayed, that tapping into our most personal and honest accounts as human beings gives us automatically a window into the universal and is what connects us all, as varied as our experiences may be. Actually, the one work that dove into my diaries was my recent solo theatrical work, Zero Grasses: Ritual for the Losses, where I drew the lines between the sudden passing of my father, legacy, my own fertility experience, and reflections on sexism and racism in the music industry from my early childhood to the present. If I feel that sharing my personal experiences, be it in grief, love, loss, or struggle, can help others feel less alone and empowered and perhaps open pathways to healing, then I happily transform private to public.

Lawrence: The M³ model emphasizes "mutual mentorship" rather than traditional hierarchical relationships. Can you describe what that looks like in practice? How do you maintain that nonhierarchical dynamic? Am I wrong to think it requires real intentionality?

Sara: You're right; it does take real intentionality. In practice, mutual mentorship means that everyone has something to teach and something to learn, no matter their age or career stage. We create structures where each person's voice is valued equally, whether through shared leadership, rotating roles, or simply making space for listening as much as speaking. The goal is to replace hierarchy with exchange, so the support flows in multiple directions, and to be as open-minded as possible.

Jen: It is the greatest joy to brainstorm these structures that subvert those old unidirectional models of teaching and learning. Whether it's through fostering co-composition between two new collaborators, having our artists moderate and run the meetings in new pairings, and really emphasizing the importance of contributing from whatever place you're at in your experience—all these modes of empowering our artists to own their gifts as well as practice humility and openness are geared toward growth for everyone, including ourselves as co-founders.

Lawrence: M³ has now commissioned ninety-two artists creating forty-six new works in just five years. How do you measure success beyond those numbers? What changes are you seeing in the creative music community?

Sara: Beyond the numbers, success lies in the solidarity and support networks artists build through M³. The larger world hasn't shifted yet, and women and gender-expansive artists still face real obstacles, but knowing you're not alone in these connections helps sustain us. Each year, our Open Call reminds me how many incredible musicians there are worldwide, and I truly wish we could support even more and create more stages for them to share their music.

Jen: It humbles us to see our artists curating festivals and music series, directing new programs in education, producing their own records as well as others', founding record labels, winning awards and receiving prestigious grants, and other festivals and workshops finally curating intentionally more equitable artist lineups and faculty rosters. However, as Sara said, there is so very much work to be done, and the disparities from city to city and country to country are very wide. We all have to learn from each other, and it's wonderful to be in dialogue with programs like Global JazzGirls founded by our M³ Cohort 5 artist Jessica Jones and Lady Got Chops founded by M³ artist Kim Clarke; and JazzCamp for Girls, Next Jazz Legacy, Women in Music, and many other wonderful programs that are changing the lives of underrepresented musicians at the same time as changing the landscape of our music world.

Lawrence: What is the interplay between your teaching practices and your own artistic work?

Sara: My teaching and artistic work are intertwined. I am fascinated by the process and love a practice-based approach. I really believe that is how we learn and improve, and what emerges as we explore and experiment is so incredible. Often, the final product isn't the most important thing; it's how we get there that shapes learning and creativity.

Jen: For me, teaching is not only a way of giving back and passing on all that I've learned, but as an artist, it affords a special opportunity to distill all the wisdom and knowledge that one has absorbed on all levels (in and, most importantly, outside of the classroom) into concepts that can then yield new creations for me. When you're inside a way of creating, sometimes it's only in the process of explaining and breaking it down to students that I realize what I'm doing in the creative process. It's like articulating things that might just come naturally to you or happen instinctively. Teaching is almost a result of one's own research. So it's all fascinating to me, and I love sharing along the way. Then your students take that knowledge and transform it from their unique experience . . . and the cycle continues, unfolding, forming, unforming, and forming anew again.

Lawrence: What were those initial conversations that led to the founding of M³? And how did talking lead to action?

Sara: When the COVID-19 lockdown began in March 2020, Jen and I started talking about how to elevate women and nonbinary musicians in our global community. Having mostly older male mentors ourselves, we saw the need for a model rooted in mutual mentorship and collective support. We drew inspiration from our work with the We Have Voice Collective, LeanIn Circles, MAP Fund's SPA Program, Jennifer Koh's AloneTogether project, and from conversations with artists and mentors like Muhal Richard Abrams, who spoke of "exchange" rather than the hierarchy of "mentorship."

Jen: When Sara and I were forming M³, we built many ideas around the holes in our formative years and education "in the real music world" when we first moved to NYC in our early twenties as female artists writing and performing our own music as well as others' music, and often being the only woman in the bands in which we performed. In terms of emphasizing the word "mutual" in our name, I remember talking with Muhal Richard Abrams at the Ojai Festival directed by Vijay Iyer in June 2017, where Muhal and I each performed on different days. As we parted ways, I thanked him for mentoring so many of us. He corrected me and said, "Now, I don't like how that implies one of us is above the other, like in a hierarchy. I prefer the word 'exchange.' For instance, I want to know more about those Taiwanese folk songs you talk about." I was humbled and surprised. Little did I know that it would be the last time I would see him before he passed away just months later. This was one of many stories that influenced Sara and me in our conception of M³.

So when Sara and I started brainstorming, I had a clear idea of how two artists could mentor each other, "mutually," in pairs. Sara had the great idea of building a group of these pairs, so we decided to start with six pairs, which would each co-compose a work and meet monthly as a group of twelve. We would premiere these six commissions at the end of our time together as a cohort. Our first cohort was very special. They asked for two meetings per month instead of one and wanted six months together instead of just three, and it was a lifeline for many of us in staying creative and connected. Then we thought of having each pair create a video with their co-composition because we realized how important visuals and moving image were during the pandemic and these years that have followed. Now we produce an annual in-person and livestreamed music festival in NYC with all M³ artists as bandleaders; as well as commissioning M³ artists to write essays and poems for an annual anthology; and then awarding our sixty-plus musicians with an annual M³ Luminary Award and $5,000 cash prize (formerly Lifetime Achievement Award). To me, we're building structures that we want to see, much like how Toni Morrison said, "If there's a book that you want to read, but it hasn't been written yet, then you must write it." And on that note, we're launching our first M³ Magazine at next month's festival, featuring all underrepresented contributors, again, producing a thing we've never seen before and want to read.

Sara Serpa - Photo by Carolina Saez / Jen Shyu - Photo by Witjak Widhi Cahya

Lawrence: Sara, how does your background in social work inform your approach to music and mentorship?

Sara: My background in social work taught me how to identify problems and seek solutions, to recognize processes of exclusion and actively address them. It also introduced me to nonprofit collectives—especially in the United States—that advocate for marginalized communities and rely on volunteers and everyday people rather than only experts, which I found deeply inspiring.

Lawrence: What questions are you both asking now in your individual work that you weren't asking five years ago? How has M³ influenced those questions?

Jen: I'm asking now, "Who isn't being heard or listened to or marginalized? How can I address this question through my hiring and own artmaking?"

Sara: My questions now are less about individual expression and more about real change: how to resist conformity, challenge algorithms, and push against systems that limit creativity. M³ has influenced these questions by showing the importance of building networks and structures that support risk-taking and alternative approaches in music.

Lawrence: If M³ accomplishes everything you hope it will, what does the creative music landscape look like in another five years?

Jen: We'll have an even more equitable music world across the globe, though the fight is long.

Sara: If M³ succeeds, the creative music landscape will be more inclusive, collaborative, and supportive, with greater visibility and leadership for women, gender-expansive, and underrepresented artists.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments