For Marcus Roberts, the supposed limitations of blindness have never defined what's possible. The Jacksonville-born pianist lost his sight to glaucoma and cataracts at age five, then built one of the most distinguished careers in contemporary jazz. He replaced Kenny Kirkland in Wynton Marsalis's band in the 1980s, performed piano concertos with Seiji Ozawa and Marin Alsop, and released more than twenty albums that privilege the stride and ragtime traditions of Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller over the bebop vocabularies that dominate modern jazz piano. By the time 60 Minutes profiled him in 2014, Roberts had already spent decades redefining accessibility in music as both aesthetic philosophy and practical imperative.

Roberts's latest project may be his most technically ambitious. Through the Doris Duke Foundation's inaugural Performing Arts Technologies Lab, he's leading "Remote Real-time Performance and the Future of Jazz," a project addressing the latency problems that have long frustrated musicians who collaborate and improvise together remotely. The goal is nothing less than enabling jazz musicians in different cities to perform, record, and share music in real time, the kind of spontaneous, reactive improvisation that defines the art form but has remained stubbornly resistant to digital mediation. For Roberts, the stakes extend beyond convenience. Software and hardware accessibility for blind musicians and production staff sits at the project's core, ensuring that new technological solutions don't simply rebuild old barriers in digital form.

The Doris Duke Foundation selected Roberts's proposal from 745 applications spanning 43 states, as part of a cohort of 20 pioneering projects exploring how emerging technologies can transform the making, experiencing, and preservation of the performing arts. His work sits alongside initiatives that use motion capture to document Alaska Native dance, develop AI tools for Black-led arts organizations, and create open-source archiving platforms for marginalized artists. The foundation's president, Sam Gill, framed the Lab's mission plainly: "These aren't just technology projects. They are ambitious proposals to radically innovate in the performing arts: how they are made, how we experience them, and who they are for."

Roberts brings to this work a lifetime of improvising around technological constraints, finding ways to adapt tools that weren't designed for blind musicians. The remote collaboration project represents the latest iteration of that ongoing negotiation between what technology promises and what it actually delivers, particularly for artists whose needs rarely drive product development.

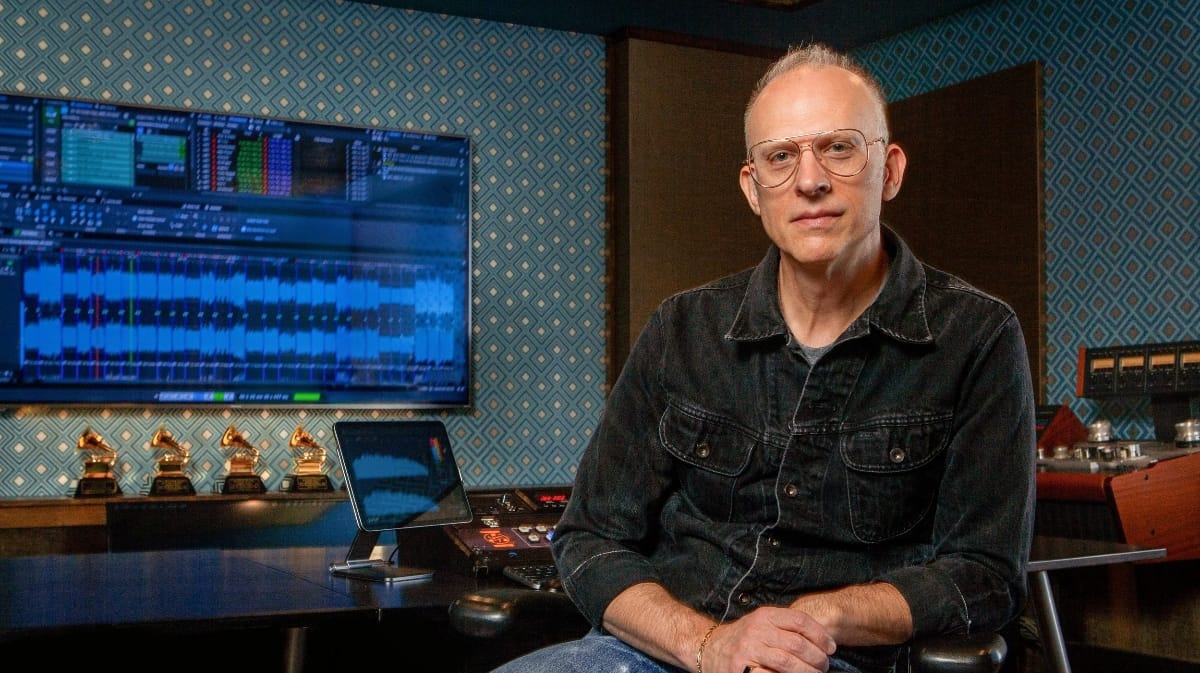

Marcus Roberts was a recent guest on The Tonearm Podcast. He and host Lawrence Peryer discussed how disability has shaped Marcus’s approach to music and technology, the philosophical tensions between organic creation and digital mediation, and why the future of jazz might depend on solving problems most musicians haven’t encountered yet.

Listen to the entire conversation in the audio player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: You’ve talked about this idea that technology can level the playing field for blind musicians and that it comes very naturally to that community because you're often searching for new technology anyway. But I can't help but wonder: are there aspects of being a blind musician that give you an advantage, either in how you hear or in how you process music technologically? I hope it's not too romantic a question.

Marcus Roberts: No, not really. Some of it is romantic. Okay, don't get me wrong. If somebody told me, “Look, Marcus, we've got some new technology, and you can get your sight back, would you rather stay like this or check that out?” The answer is 100 percent, “Yeah, sign me up.”

That being said, we all have issues and struggles that we have to cope with. Everybody has something they're dealing with that they would probably prefer people not necessarily know or not dig too deep into. Obviously, if you see somebody with a cane or a dog, you know they're blind, so you could make judgmental assumptions about them without talking to them or knowing anything about what they do. You can use that to assess their potential, again without even knowing who they are. If you have a condition or a situation that you cannot identify through sight, and it's not to say people are hiding it, but you don't see it. So I think in that sense, there's an unfortunate component to certain disabilities where people can make assumptions about you.

To be honest with you, early in my career, I never wanted to discuss my blindness because I didn't want anybody to think that that had anything to do with what I was capable of doing. But over time, and after decades of being out here doing this, I thought, “Well, you know what, if I talk openly about it, maybe people will find some inspiration in that.” Or maybe talking about the struggles and the things that might be advantageous, that you've forced yourself through working on things day and night, you've turned something that was once a deficiency into an asset, which is kind of what we all want to do.

For example, anytime I'm on the bandstand, I'm not up there to mess around because I can't visually look out and look at the blonde in the third row. You know what I mean? Like, it's music. That's it. I'm up there to play, and I'm listening to the environment that's being created around me and trying to figure out what the piano has to do to make this work, to make this better. How can I make more room so that what somebody else is playing can be heard? These are the things that I tend to think about on the stage. And again, you can carry that into your life. Like my father used to always tell me, “Look, you got two ears. You should listen twice as much as you talk, and you'll learn a lot more by checking out what other people are saying.”

In terms of any advantage, I think you create the advantage through your work ethic. You create the advantage by not looking at yourself as a victim. Instead, see yourself as a resource for improvement through the work you do, and when you need help, don't be afraid to ask for it from people you trust who care about you and have information you don't.

Lawrence: There's a tremendous vulnerability that it sounds like you have to embrace, but like with most forms of vulnerability, if you can embrace it, it opens up a lot of opportunity.

Marcus: Yes, yes.

Lawrence: I want to ask a little bit about your relationship with creative technology and studio technology. Because you used the phrase 'asking for help,' I'm wondering how much you have to advocate or even invent to maintain your creative life. You know, I imagine, like with many tools, accessibility doesn't seem to be at the forefront of product design.

Marcus: No, no, no, no. (Laughter) Being jazz musicians, we improvise for a living. And you find yourself doing that in this type of environment with a vision problem. You find ways to modify something that kind of works, and you fool with it and tamper with it, and you're like, “Oh, actually, if I do this, it works.” A lot of blind engineers that I know, my goodness, the tools that they have found, and a lot of them are free tools, all kinds of tools that they're constantly coming into contact with. They'll teach me about them and say, “Look, if you use this, your voice will sound better. “ And you didn't have to drop like twenty grand for a Fairchild compressor. You know what I mean? Like, a lot of this stuff is now available.

I'll tell you one of the big moments. I was in Japan working with the great Seiji Ozawa, who conducted the Boston Symphony for years. He had a blind violinist with the Saito Kinen Orchestra. This was 1997, and I'll never forget, we were on break. And I wanted to meet this guy because, you know, how this is, it's like any tribe, you want to meet your people. He's a blind guy. First, I wanted to know, how do you even know when to come in? They don't go ‘one, two’ or ‘one, two, three.’ They don't do that. So I was trying to figure out how do you know when to come in with that orchestra? He gave me some explanation that the next guy sitting next to him—I don't know what they do, but they had some kind of system.

But we were talking, and he says to me, “Look, there's a new device that just came out, and you can load Braille documents into it, and you can check your email.” I was like, “What?” I didn't believe it. He showed it to me. It was the Braille Lite M40 from Freedom Scientific. He showed it to me, and I'm not going to lie, that was like a life-changing moment, second only to when I was eight years old and came home from elementary school, and my parents had bought a piano. They didn't tell me, and I bumped into it as I went into the house. At first, I was pissed. I was mad like, “What is this? What's in my way?” And it was a piano.

So, that violinist showed me that device. Since then, I've probably bought five or six of these Braille notetakers. They're basically like our version of an iPad, I guess you might say. They're not cheap, I'll tell you that. They average anywhere between three and five thousand dollars. None of this stuff is cheap. But the revolutionary nature of the technology and what it allows us to do, especially in terms of being literate, because I believe in reading Braille whenever I can. And one of the unfortunate aspects of our community is that our blind children, even with all of this technology that's happened and all the innovation and all the opportunity, the literacy level in the blind community is still 10 percent. It really bothers me, and some of it, of course, is that a lot of kids are priced out of being able to afford this technology. Hopefully, through government and state support, we can get these children the devices they need to learn.

Lawrence: A lot of them are very talented, but my argument is, why do they have to be talented to get a fair chance? There are a lot of ordinary people who do just fine, and they don't have to be Albert Einstein. Or we may never find out what they're capable of.

Marcus: That's exactly right. And I was blessed early, like I learned Braille when I was six and understood somehow, intuitively, how important it was to learn how to read and write. That was my journey, and I was fortunate to get good piano teachers who could really teach me how to play. My first teacher, Hubert Foster, who was also totally blind, he was a genius. I mean, he had a master's in voice, and he knew how to build pianos—just an incredible guy. He made me learn Braille music notation.

Braille has several modes. The first one was actually Braille music. Louis Braille was an organist, and he wanted to play organ music. And now there are three types of Braille music notation. I learned all three of those. There is literally a computer science code. There's a Grade 2 Braille code for the United States, and then they worked on something now called UEB Braille, which is the standard. I grew up doing just US Braille. So it's taken me years to realize, okay, you're going to have to learn this. You have to learn this UEB Braille.

So all of this stretches your mind and imagination. I've been working on the Sibelius notation program for years and years because, you know, as a blind composer, I've got to figure out a way to write my music. Ultimately, if it's a work for a symphony orchestra, these are sighted people. They don't read Braille music. So you've got to give them a score and parts, like what they're used to, and what I tell all my blind students that I have, the ones that I work with, is that their lives will be much simpler if they remove as much of the problems that their disability causes them, if they can remove as much of that from other people's lives as possible.

People will help you. But if they have to help you do stuff for hours and hours all the time, they're going to get tired of it, and people are human, and you're going to have a problem. So you need to do everything you can to make it easy for people to help you. That's very, very important. You need to be very conscious.

Lawrence: I read where you said music has to come from the body, from us. I love that for a lot of obvious reasons. But then technology becomes an interface for accessing and creating music in ways that sighted musicians take for granted. There's this interesting tension between the naturalness of the body and the inorganic nature of technology. How do you think about that?

Marcus: It's really a wonderful, truly complex statement because I actually consider myself, despite my scholarship and willingness and desire to learn as much as I can all the time, a natural musician. For the first four years I played the piano, I couldn't have told you the difference between E-flat and B-flat. But my mother always made me play. She wasn't a trained musician, but she was a great musician because you could feel something when she sang. And she always told me, “I don't feel anything from what you're playing, so you're going to keep playing it until I feel something.” “Yes, ma'am!” And so I learned early from her that the most important thing we have as musicians is to communicate a feeling to people. That's why people are attracted to whatever they're attracted to. They feel something from that.

I think learning that early on is the top thing that I've worked with my students on: why are you playing what you're playing? Like, what are you trying to communicate? What message? I mean, are you communicating sadness? Are you communicating hope? What's the feeling you want people to get from what you're doing?

Technology does sometimes get in the way because if I'm at a computer, I've got all these keyboard commands, and I'm going to play something—okay, well, I've got to press this command to get into Flexi-time, and I've got to set it to quarter notes because I'm primarily going to be playing quarter notes right now. You know what I mean? It interrupts the naturalness of just hearing and playing. But at the same time, if I get it right, it's beautifully notated, and people can read it.

There's a lot of knowledge you need, but the ultimate goal is to hear, feel, and communicate to the public. The first level is self-expression. So when you're teaching young musicians, first you ask, “Do you have something to express?” You teach them how to express. The next level is, “Can you communicate a feeling to people? Can you communicate it clearly, accurately, with good technique, with a good sound, with a good tone, with a knowledge of stylistic influences that you bring to the table?” Then the final level, and the one I'm always looking for with me and my audience, is to reach a state of communion, meaning we all feel this, and their feeling is energizing me to play stuff I never would have played without them.

Lawrence: I love that. There's something else that occurs to me as we're talking, which is, I'm a man of a certain age, and I grew up loving technology and music. I used to think of myself as sort of a techno-optimist, and, well, it's a hard philosophy to still embrace in this era. And I think something like what you're doing reminds me that technology's at its best when it's in the service of a larger human mission and not technology for its own sake and for its own novelty.

Marcus: Amen. I think Dr. King spoke to that. He said something like, you want the human moral compass to always be ahead of the technology, because if you think about it, all technology is automating some natural process. Somebody automates it and makes that possible or accessible to somebody who doesn't have to go through that manual process. Sometimes that can work against you because maybe you don't understand that manual process, and you're kind of skipping through some steps. But I'm okay with that sometimes. And you know what? I don't really need to know the details of it. It works well. It saved me an hour. Thank you.

Like you were just saying, if it enriches your ability to create and if the technology helps provide a naturalness and organicness, I think that's beautiful. Some of my jazz friends hate editing. They think it's false. They think it's fake. They don't believe in it. I'm like, what do you mean? You're just editing something that you actually played. I mean, why would that be cheating?

Lawrence: I mean, if it was good enough for Miles, it's good enough for me. (Laughter)

Marcus: Who are you talking to? Hello? We know Miles had all kinds of crazy editing that was going on on some of those records. Well said.

Lawrence: I read a quote from you about how if AI reaches the intelligence that all the tech prophets say it will, the first thing AI is going to say is, “We don't need you.” Given that and given the sentiment in Dr. King's quote, I'm curious how and if those ideas influence or inform the choices you make about the technology you embrace. What is the technology you resist?

Marcus: It's all experimentation for me. I try things. If they work and make my music organically accessible to people, I'm okay with it. If it gets in my way, slows me down, or makes me feel that what I'm doing is less authentic, I don't want anything to do with it, because for me it's all about authenticity.

But if you go to a restaurant and you know the food's good, what if AI cooked the food? I don't know.

Lawrence: Did they microwave it? (Laughter)

Marcus: I don't know how they did it. Somebody, somewhere, had to make a decision to make the food good, whether they did it all themselves manually or used other processes, because we've always used technology. A car is a technology. A piano is technology. You can’t grow a clarinet or a saxophone on a tree, either. So I think the key with technology is: what's the intent? What's our intention with it? And I think that's where the danger and the glory come from. How are we going to use this tech? Are we going to use this technology to uplift people or exploit them? Are we going to use this technology to inform people or deceive them?

Lawrence: When you look back over the last five or ten years, have there been any technology breakthroughs or tools that you wouldn't have thought were possible? What's excited you?

Marcus: Well, there’s the Braille Sense, and a company in Korea makes it. They have a small but brilliant staff of folks who work on this product. The user interface is very simple. If I want to hear Miles Davis, I type it in there, I hit enter, and boom, it's playing in like three seconds. It's got a podcast app, so a lot of the podcasts that I'm into are there. It's got a fantastic, straightforward YouTube app. It's got a Braille display, and I can read and write on it. So that’s not necessarily something I thought wouldn't be possible, but I didn't think it would be this easy to assemble all these things.

And there's been a lot of progress made with Sibelius; it's still difficult to use, I will say. But I can produce major orchestral works with it. Like I just did an arrangement of James P. Johnson's "Yamekraw" that I recorded with the Cincinnati Symphony in March. I guess we'll put that out sometime next year. But I did all of that. I couldn't have imagined I could do it with this level of professionalism even ten years ago. So those are just some quick examples.

And then in the case of what we call screen readers, which are the software that interprets the screen, computers are completely accessible. So if you want to create a complicated Excel spreadsheet, you can. If you want to write a complex document with all kinds of graphs and tables, you can do it. I mean, all these things are being done at very high levels, and we've got many blind computer programmers, physicists—I would argue that our community is one of the most diversified in the world.

Lawrence: You know, when you were talking about the Braille Sense interface you have and all the different apps available now, I was thinking, “Oh, so now Marcus can waste his time online like the rest of us.” (Laughter)

Marcus: Yeah! I get right into that rabbit hole!

Lawrence: We've finally done it as a society; we can finally waste blind people's time too.

Marcus: Oh, we are the worst! Oh, my goodness.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments