Ahoy, reader! This was not the best weekend for assembling a newsletter with so many distractions, worries, and triumphs (those 'No Kings' attendance numbers are astonishing) to keep me at bay. So I apologize for its lateness, shortness, and lack of recommendations. But there's still plenty to dig into! There are many terrific interviews and pieces in The Tonearm I want to tell you about, and, as usual, they sent my brain spiralling downward through unexpected rabbit holes. Won't you join me? Let's explore:

Surface Noise

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

Charming Disaster's Ellia Bisker and Jeff Morris regularly interrupt a live performance by asking an audience member to choose from their 72-card oracle deck. This adds both audience participation and a touch of randomness to the show as each card represents a song or challenge for Charming Disaster to perform next. But, as the duo appreciates a bit of drama, there is also a sense of tradition and sacred theater embedded in the maneuver.

The idea would have been familiar to Pamela Colman Smith, the artist behind the world's most recognizable tarot deck. Working in London around 1910, Smith incorporated her mystical stage set designs for W.B. Yeats and the 78 cards she illustrated that would become the Rider-Waite tarot. Her tarot cards borrowed directly from her theater work—dramatic lighting, casting shadows, figures posed in theatrical tableaux, and costumes heavy with symbolic meaning. Smith understood that tarot readings and theatrical performances require the same leap of faith from their audiences. Whether you're consulting cards about your future or watching actors pretend to be other people, you must agree to temporarily suspend disbelief and accept that meaning can arise from artifice.

Charming Disaster tap into this same understanding. Their oracle deck performances work precisely because they honor both the mystical and theatrical aspects of card-based divination and refuse to separate entertainment from enchantment. As audience members select cards, they're participating in a collaborative act of storytelling that Smith would recognize. The cards become both script and director, determining what will be performed and, in turn, how the evening's narrative will unfold.

Playback: Parallax Point — BANKERT's Constructed Cosmos → BANKERT speaks of working within "carefully prepared settings" while allowing for improvisation, much like how Charming Disaster create structured frameworks for spontaneous performance. The description of their studio as "a kind of observatory" where "drift and discipline" coexist mirrors the dual nature of divination practices that require both preparation and openness to chance.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Often, as Kinan Azmeh performs "Daraa" for international audiences, its melody, which once united millions of Syrian protesters in the streets, reaches the ears of people who have never heard of the song's namesake. In this southern city, the Syrian uprising began. This disconnection between lived experience and received performance—Azmeh has yet to perform “Daraa” in his home country—raises intriguing questions about how cultural memory travels through exile. Stripped of their immediate political context by unknowing listeners, these melodies don't lose their meaning but find new forms of universality.

This presents what might be called the immigrant artist's essential dilemma. How does one preserve cultural memory while making it accessible to new audiences? Azmeh must honor the original voices while creating music that can function in contexts where those voices would otherwise be unintelligible. Too much preservation and the music becomes an ethnographic artifact; too much translation and it becomes mere exotic decoration.

This transformation accelerates when the piece reaches international concert halls. These venues then become an unusual kind of archive, and the clarinet in "Daraa" a vessel for voices that can no longer speak for themselves. Introducing the song during live performances, Azmeh announces that "the dictator is gone and the melody has survived." He's demonstrating how music can outlast the political circumstances that gave rise to it. The melody that once carried specific demands for freedom now carries a more abstract but no less potent message about resilience and resistance.

Playback: Mauricio Moquillaza Builds a Platform for Peru's Sonic Experimentalists → Mauricio Moquillaza’s creation of Deshumanización reflects the broader challenge of preserving authentic cultural expression while making it accessible to audiences who might view experimental music as "alien." His emphasis on creating "a place for discussion and listening" mirrors the concert hall spaces where cultural memory requires both preservation and interpretation.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Pat Metheny's 1994 album Zero Tolerance for Silence occupies a unique position in the catalog of artistic self-sabotage. Unlike Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music or Neil Young's synthesizer trilogy, which carried traces of their creators' established identities, Metheny's noise album felt like complete ego death. The man who had spent decades perfecting crystalline jazz guitar suddenly sounded as if he were torturing his instrument in a concrete bunker. No melodies. No swing. No recognizable connection to anything in his extensive discography. Just pure, unrelenting sonic brutality.

Arthur Arsenne was twelve years old when his father played him Zero Tolerance for Silence and has spent decades unpacking its implications. That moment inspired Arsenne to embrace the harsh fringes of sound-making, introducing him to artists like Sunn O))), Boris, and Merzbow, and eventually leading him to found his Arsenic Solaris label. His work with Toru—creating what he calls "sonic mille-feuilles" by layering processed guitars until they become unrecognizable—directly connects to techniques Metheny pioneered on Zero Tolerance. Arsenne describes routing eight-string guitars through modular synthesizers or transforming familiar instruments into alien textures as he follows the album’s unlikely influence.

Making music with no commercial expectations, no audience to please, no reputation to maintain, is a liberating thing. Zero Tolerance captures that freedom in its purest form. It’s the sound of an artist with nothing left to lose. That energy translates even decades later, inspiring musicians like Arsenne to embrace similar fearlessness in their work. His Arsenic Solaris label, dedicated to "dark, esoteric, experimental, and radical music," operates in the same spirit of beautiful commercial suicide.

Playback: The Strange Science of Breakcore → The Tonearm’s Anthony David Vernon described the genre of breakcore to us as "antithetical to music as being any sort of science,” while paradoxically being deeply scientific in its chaos. Breakcore’s abandonment of melody and swing in favor of "inhumanly chaotic" drumming and sonic brutality, as well as its embrace of dissociation and psychological expression through sound, is, in this context, its own sort of ego death.

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

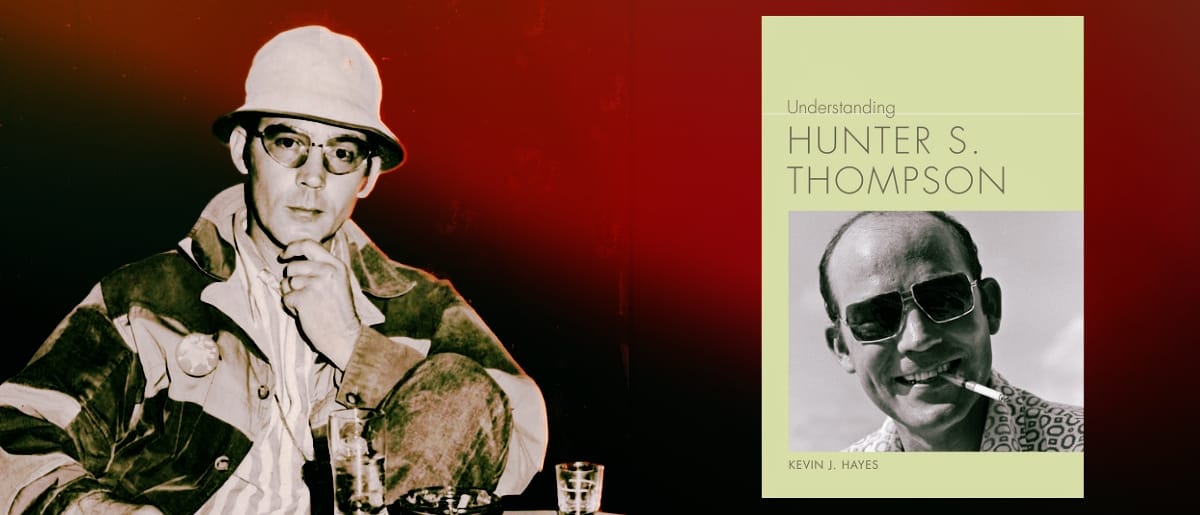

In his book Understanding Hunter S. Thompson, author and scholar Kevin J. Hayes states that there is only one Gonzo journalist, and anyone attempting to follow in Thompson's footsteps becomes "just a wannabe." It's a provocative statement that captures something genuine about Thompson's unique position in literary history. However, it also highlights a broader cultural phenomenon worth examining: how the concept of the "unrepeatable" artist functions as a sophisticated gatekeeping mechanism.

It's true that no one has successfully replicated Thompson's particular alchemy of immersive reporting, literary flair, and personal chaos. But the broader implications of declaring any artistic approach "unrepeatable" deserve scrutiny, as there's a danger of freezing that artistic territory in time. Authenticity, viewed this way, is trapped in a kind of circular logic that Hayes, to his credit, seems aware of even as he participates in it. Thompson is deemed the only "real" Gonzo journalist, not necessarily because his best work is objectively better than anyone’s that followed, but because he was the first. He lived the lifestyle and embodied the chaos he wrote about. But, as Hayes notes, Thompson's actual productive output was remarkably brief—roughly four years of peak creativity followed by decades of decline and missed opportunities. If authenticity were truly about literary quality rather than biographical mythology, wouldn't we want writers to take Thompson's innovations and push them further?

Hayes's background in early American literature may illuminate why Thompson's case feels different to him. As he notes in the interview, his specialty prepared him for "studying something that shades into nonfiction, that shades into fiction"—the kind of hybrid approach that Thompson perfected. Hayes understands how Thompson's work fits into American literary traditions stretching back centuries. This deep historical perspective might make Thompson's particular synthesis seem even more distinctive and unrepeatable. But the authenticity trap doesn’t need to define how we think about artistic inheritance and innovation, even when—perhaps especially when—it involves figures as culturally loaded as Hunter S. Thompson.

Playback: Cry for Revolution — The Transformative Pedal Steel of Susan Alcorn → The late Susan Alcorn shared her experiences with authenticity gatekeeping, in which fellow musicians dismissed her experimental work as inauthentic, claiming she didn't know how to "really" play the instrument. Even for someone as celebrated as Alcorn, authenticity becomes trapped in circular logic where innovation gets dismissed simply because it deviates from the original approach, regardless of artistic merit.

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

Following Brian Wilson's passing this week, three writers at The Tonearm (including me) composed tributes to the Beach Boys' inspirational sound architect. Sara Jayne Crow traced Wilson's complex history, from his early formation of the Pendletones through the commercial peaks of surf music to his decades-long battle with mental illness, abuse, and exploitation—all while seeking the sanctuary he could only find in his music studio. Lawrence Peryer unearthed a deeply personal journal entry from November 2006, written after attending Wilson's Pet Sounds 40th Anniversary Tour. His account captures the emotional impact of witnessing Wilson's vulnerability and grace on stage despite years of trauma and heartbreak. And then I reflected on Pet Sounds' lasting influence and how the album's cute animal-adorned cover convinced my six-year-old self to choose what remains my most meaningful musical discovery.

It was a moving experience to quickly compile this article and express Wilson's enduring legacy as both a troubled genius and an inspirational figure. His music provided refuge for countless listeners, like us, as they navigated their struggles. We'd love to hear your stories and remembrances, too.

Run-Out Groove

Short but sweet, right? We'll make up for the lack of recommendations next week, I promise. I'll give you one now, though: Mary Halvorson's new album About Ghosts is phenomenal, and Halvorson is soaring here as a composer and band leader. I feel like improvisation is at its best when the whole band, rather than one instrument, consistently stands out, and About Ghosts certainly fits that bill.

Please let us know your comments, suggestions, vegan recipes, and more—reply to this email or contact us here. And forward this newsletter to one friend—or one hundred friends, I'm not stopping you—who you think will enjoy it. You can even share a link to it on your social media Sauron of choice.

OK, this was nice. I feel a lot better now. How about you? Stay hydrated as you engage and safely confront the world—it's hot out there. I'll see you next week! 🚀

Comments