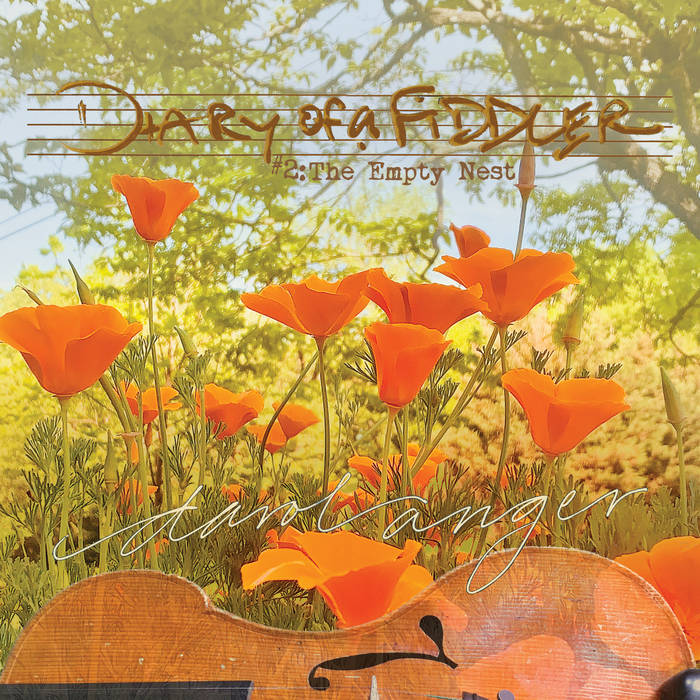

Looking back on one's career and accomplishments with reverence is a sign of a life well lived. Sharing that passion with others is just the cherry on top. Grammy-nominated and legendary acoustic musician Darol Anger shares the fruits of his fiddle mastery with pupils and a new generation of players on Diary of a Fiddler #2: The Empty Nest. With a jaw-dropping guest list, Anger assures listeners that the world of new acoustic fiddle music is in nothing but the best of hands.

The September release of Diary of a Fiddler 2 coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of the David Grisman Quintet recordings, to which Anger contributed his talents and compositions. He credits Grisman with giving him a chance and a job with the group, which is now one of the most legendary outfits in the history of bluegrass and new acoustic music. He has gone on to become a world-renowned instructor of the violin and Professor Emeritus at Berklee College of Music. The record's celebratory attitude is prescient from the very beginning of "Liza Jane Parade," which is a remotely recorded and improv-heavy cacophony of bows and strings featuring twenty-two musicians. It almost feels like a last day of school party, but with fiddle cases and bow rosin in lieu of pizza and sodas.

Guests on the record and students of Anger's are likely found in your favorite contemporary bluegrass bands, such as Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway, Punch Brothers, and Billy Strings. His influence on the world of fiddle players cannot be understated, and that is a fact Diary of a Fiddler 2 will reinforce for many further generations to come.

Darol Anger played fiddle with the Manzanita band on the 1979 Tony Rice record of the same name, which is an album that means more to me than I can put into words. His break on "Old Train" rings throughout my head most days of the week; its ending still gives me goosebumps after hundreds of listens. It was an honor and a privilege to speak with him about the upcoming record, the family nature of the fiddle community, and how he reflects on a lifetime of creating and teaching music. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Sam Bradley: In the spirit of the record, I wanted to ask about your early days first. What was the moment you recall wanting to follow music?

Darol Anger: When I was a kid, we bounced around quite a bit. I was born in Seattle and went to New Jersey for a couple of years, and those were interesting years—'63 and '64. I was ten and eleven, and in those years, of course, the Beatles came in, the Kennedy assassination happened, all that stuff. While I was living on the East Coast, I was exposed to pop radio, and it was really where everything was happening. My teen years were spent in California, then the subsequent twenty-eight years were in the San Francisco Bay Area. That was a good place to be for music at that time—'67 through '77, really. FM stations were incredible at that time.

As far as me wanting to do music, that inspiration at the time was just by the Beatles, you know? It kind of ruined any kind of pure style, really, whatever that means. Styles, of course, always being a combination of two or three other styles.

Despite having started with guitar, I quickly went to violin just because I didn't have a guitar that was physically playable. You know, back in those days, you could get a good guitar, you could probably get a cheap guitar, but you couldn't get a good cheap guitar. Now you can get a great, cheap guitar. Of course, my folks didn't know whether I was going to stick with it or not, so they just got something inexpensive, and it wasn't really playable. But then one night we were in a restaurant and some guy was strolling with a violin, just walking around tables and playing stuff solo. I just thought, "Man, it just looks so cool." He just seemed to be having a great time. I said, "Whoa, man, that looks a lot easier than the guitar. Well, I'll play that."

Even though I was really into music, there wasn't really a fiddle track for where I was living. I didn't even know fiddling existed until about halfway through high school. Of course, by high school, I had already gotten back to electric guitar and was trying to figure out Clapton solos and Jimmy Page stuff. I had already kind of used a little bit of the theoretical knowledge I had gained from studying violin to apply to guitar, which is great because with guitar, it's almost like the map is the territory. You have spacings, dots, and lines to see where you're going. You can look at it and kind of make shapes.

One day, I went to a rock concert—the Youngbloods—because they actually had a violin part in one of the tunes. Opening for the Youngbloods was a band called Seatrain, which featured a guy named Richard Greene. Richard Greene is the kind of brilliant, kind of crazy fiddle player who sort of moved Bill Monroe's music forward. He had been inspired to play himself by Scott Stoneman, who was probably the craziest fiddle player ever. So that put me on a path by thinking, "Oh, well, there are already two hundred guys ahead of me just in my high school on electric guitar, but if I switch to violin, I'll have a niche! Nobody else is doing that," well, at least that I knew of.

Sam: Do you remember the first fiddle tune you learned?

Darol: Yes. I'm embarrassed to say, but it was "Orange Blossom Special." I learned it because Richard Greene played it, you know, in the rock band, and it was amazing. He went on and on and on, and it was in E. He played all these shreddy guitar licks, and it was amazing—that's what I wanted to do. The second tune I learned to play was "Sally Goodin," which is really one of the most basic bedrock fundamentals of fiddling. Between those two, I've landed somewhere in the middle, I guess.

Sam: To flash forward a little bit, something I had written down was how, from the very kickoff of the record, on "Liza Jane," it has this celebratory quality. There's a familial atmosphere to it. Could you touch a little bit on the attitude and overall vibe of the sessions?

Darol: So this project began during COVID, while everybody was stuck at home. I'm going like, “Let's do a project, and I'll just record something and then I'll send it out to everybody and they can overdub on it." As far as the people on the record, I kept thinking how I've got all these kids—well, I think of them as my kids. They're not kids. They're fully grown adults and matured artists. For that opening track, there are twenty-four people playing, so the twenty-second person is going to go like, "There's no more room to play anything. What am I going to do?" So I hit on the Jaco Pastorius thing, right? On that first cut on Word of Mouth, he sent a track around of this abstract thing and had a bunch of people just improvise over it, then he put that out. That was the lead-off track. I thought, okay, I'm going to do the same thing.

Nobody who plays on the track hears anybody else but me, and we're doing the tune in a second line style, right? So it's like a New Orleans parade, trying to have it up and be fun and crazy, everybody can improvise and do whatever they want. We're doing it in E-flat, which is interesting because some of the fiddlers, especially some of the old-time fiddlers, don't want to play an E-flat. I said, "So just tune up a half step. You can play D, do whatever you want, you know?" So that was fun. I just wanted something that grooves like crazy. I think everybody was just happy to have something to do, you know, something to play with. They got to kind of work out their overdub thing at their home. I think it was just kind of an explosion. When I listen to that, I just can't stop laughing. It's just a beautiful thing. Everybody just completely had the room to be themselves, and so you get this fantastic profusion of just gorgeous, incredible sound. Everybody knows everybody on that cut. If we were in the same room together, it would have been great. This is a real community, and I feel like I'm one of the connector points there.

Sam: There are so many collaborators on the record. Did anyone change your outlook on how you envisioned the record from the start?

Darol: I think it's pretty much my vision. Part of the thing with this was that I knew there was going to be a lot of material on here, and I didn't want to pay publishing royalties. So it's all my compositions, except for the "Liza Jane," of course, which is traditional. That worked well because I've been writing music since 1977, and I had a pretty large catalog of things to match up with people. That was part of the joy—trying to match the tune to the person. I had a lot of help from Brittany Haas, who I consider a family member. She helped me out with some of the choices there. One example is that we decided that we were going to adapt this rock and roll tune that I wrote a few years back. Initially, I didn't think that it could be done with two fiddles, but she turned it into something that I think is one of the most effective things on the record. That song is called "I Coulda Told U," which is basically just rock and roll.

I’ve had a pretty intense musical interaction with all of these folks at some level. Often, you know, kind of a teaching thing like at Berklee College of Music. Some of these folks were there for a couple of semesters, so we're used to just playing and improvising together. Even though they sound like these really arranged magical things, it's all improvised. A lot of the endings—almost every ending is completely improvised. We don't really know what we're going to do; let's just do it. All in all, these folks have the ability to really play a lot of accompaniment and make it a much bigger sound.

Sam: How did you get involved with the world of teaching music? I know some musicians can have a complicated relationship with music education, and I was curious how you found that to be a calling?

Darol: Yeah, I mean that's such an interesting thing because you get shaped by ideas of what you don't want to do as much as what you do want to do. I've been inflicted by some pretty bad violin teaching, as well as some pretty great violin teaching. I think that teaching is a whole different skill from performing, and it takes a while. I think what makes a better teacher is having really struggled with the mechanics of trying to play in the first place. If you start off with a lot of talent and everything's working for you, it's much harder to teach because you've never struggled to figure out how to do stuff. I definitely struggled, you know. I feel like one of those people who probably started recording before they really should have—before they were really ready to present a finished project to the world. But be that as it may, that's what happened, and it's fine. I'm feeling more like I do now than I did before.

I started teaching kind of before I was ready to, so it really put me in a mode of panic where I felt like I really had to do something. I did have some amount of background in theory, and I was always interested in it. I had to puzzle a lot of it out for myself, but it wasn't like I was starting from zero. The thing that really made it possible to do that was the music camps, you know, the fiddle camps. Then, just getting hired at Berklee in 2008, I believe, by one of my oldest friends, Matt Glaser, who is also one of the most influential people in this kind of music. It's wonderful just talking to the faculty there. Most people go, "I dread meetings. I especially dread faculty meetings," but these were some of the most educational and exciting experiences that I've had! We're just getting down to like, "Well, what can you teach?" You know, what can be taught? It's easy to work with people who have that kind of ability, and that goes for the students, too.

Sam: It must be a rewarding feeling to have been invited into those circles, and not dreading meetings!

Darol: Absolutely. I feel like every step I've taken in my whole musical life has been so lucky. It seems like I'm probably the luckiest fiddle player ever, so that's been great.

Sam: What are your thoughts on the current state of bluegrass music? Does it feel to you like there are periods of highs and lows, and does the current day fall into either of those categories?

Darol: I think one of the things about this kind of music—meaning acoustic music and roots or string band music—is that bluegrass is sort of one end of it, the high-functioning sort of technical end of it. Then, at the other end, it might be something like old-timey music, which is also quite technical. I mean, all music has a technical side to it. Most of the people who like this and are fans of the people who play this kind of music are musicians. They play an instrument, or they sing, or they do something.

A lot of pop music is sort of about what kind of clothes you're wearing, what you're smoking, or some sexual fantasies or this and that. There's a certain amount of hero worship there. With this music, it's more like the people that are on stage doing the stuff are just sort of doing R&D for the audience. We're just actually doing research and development for them—"Here's something you might want to try," you know, "try playing this with your group and or local jam or something like that. Here's a tune you might want to check out."

It's sort of like the great American hobbies. It's like car clubs where people who work on cars also drive cars. Bluegrass is like any kind of scene where all the people involved are kind of doing it at some level. I think that's why it's so robust—because it's really a community that is about something that is real, in the sense that everybody is interested in doing it. That's kind of an abstract way of saying it, but everybody's involved at sort of a maker level. That's what I love about it. I get off the stage and can go over to the merch table, and I can talk about fiddling—somebody comes up and asks about playing in a funny key, or how you get your fourth finger working properly. With the audience connection, it's mostly just all these kinds of little tweaky, little geeky things. You can geek out with pretty much everybody who comes to the show.

Sam: So you feel it's less insular, just more of a welcoming geeks club? That would certainly be no surprise to me.

Darol: Yeah, I think also the older musicians are respected too—the age thing actually can be to some extent a plus. I’ve known people I’ve respected and admired so much, like Vassar Clements and Byron Berline, who are renowned fiddle players. There are people who were just ten years older than me, people like David Grisman, who gave me my first job playing professionally in front of people. This kind of music will show you the depths of commitment to the music. It's clear to hear that in the way people play.

Sam: You just mentioned working with David Grisman, and I know this record somewhat coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of that group getting together. How did that opportunity present itself, and what sort of lessons did that experience teach you?

Darol: There's an old saying: Luck favors the prepared mind. That definitely worked out in that regard because I was a big fan of David. I had gone to a concert of David's band with Richard Greene, which was sort of the precursor to the David Grisman Quintet before Tony Rice was involved. I actually brought my tape recorder to that particular concert and learned all the repertoire. I learned all the melodies and harmonies and all of Richard's parts, most of his improvised solos, too. When I finally had a chance to meet David, I kind of knew a lot of his repertoire and kind of knew what to do. I was still pretty green and technically had a ways to go with it. I had a love, and I think an understanding, of what the music was supposed to be about. I think David appreciated that a lot. Plus, I kept showing up and wouldn't go away!

Then, of course, David got Tony Rice involved in the project because the material was so good and it was so original. It just used a lot of the skills that a good bluegrass player has to have—pretty technical stuff. The standard that David and Tony set for technical execution and just excitement and the groove—I mean, Tony is a God to so many guitar players. You know, standing next to that guy, you pick up stuff just naturally through your body from getting to stand next to somebody like that. That goes for a lot of amazing fiddle players, too. If you stand next to somebody and you pay attention, you can pick up a lot. It all taught me to pay attention.

Sam: Absolutely. Persistence with a purpose, or maybe persistence with an open mind, makes perfect.

Darol: Oh, that's great, I love that.

Sam: I have to pause to admit, I am one of those guitar players. I am a huge fan of Tony and know you guys worked together many times, those recordings being very near and dear. What about his presence impacted you musically?

Darol: As you can imagine, it was pretty intense. Tony was an intense guy. When you decide to go into the guitar gunslinger contest thing, that is very high pressure. Tony was just trying to make the best music he possibly could. It turned into almost a moral issue, which was really interesting. It certainly straightened my back, you know, as far as just going, "Oh. Okay. Okay, you’ve got to take this seriously." And there's such a thing as taking stuff too seriously, but really being around him and seeing how he did things and how much thought he put into the stuff, it really taught me what to do and what not to do. We were very different people coming from very different backgrounds. A lot of times, I'm just like, "Man, I'm just so glad I'm not a guitar player."

Sam: Well put. I wanted to ask about what you hope people take away from this record. As something with such a personal and celebratory touch, what are you hoping that people feel from this record?

Darol: I hope people just really sense the love and the fun. We're just here to goof around and have a blast. It's like running around screaming sometimes, you know, but sometimes it really makes for just the most beautiful moments. We've taken these songs and are just trying to find the hidden little wildflowers and whatever's out there in the grass. This is what happens when you can just have a good time at a high musical level.

Part of it is the question of why you want to get good at playing the fiddle. Why would you want to do that, you know? Is it to win a prize or get paid more, or something? Or is it just to have a great time playing with your friends?

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmMichael Centrone

The TonearmMichael Centrone

Comments