Kathy Kennedy describes herself as a community artist, and not only does this come through in her work and politic, but this relationality reveals itself in the way that she shows up as an interviewee. "Where are you, Meredith?" she asks with curiosity when we begin discussing her personal background. I quickly pivot the conversation back to her and Montreal. "Am I doing the right thing?" she asks, regarding her Bandcamp-plus-printed-booklet release model, with palpable interest in my answer. I do my best to provide her with one, but I don't know. She's the expert here, and her knowledge is humblingly vast.

Kennedy tells me she teaches electroacoustics, and it shows. The way that she describes sound and its interactions communicates this interest in how sound behaves, especially where groups of singers are involved. And has she just made music in sterile auditoriums? Of course not. She has brought groups of people into public spaces, aided by boomboxes tuned to the same pirate radio station, to distribute the sound they made together, the kind of statement that takes guts, creativity, and complete conviction. This is just one example; the retrospective of her work, Singing Off the Grid, contains much more.

There's a spiritual connotation to what she does as well, drawing on the influence of Pauline Oliveros, legendary for her pioneering work in 'sonic meditation' and 'deep listening.' Go to Kennedy's humble YouTube channel, and you can see her approach in action: a group of singers, phones and boomboxes in hand, walking through a park, singing the words "here" and "now" as their voices rise around a note.

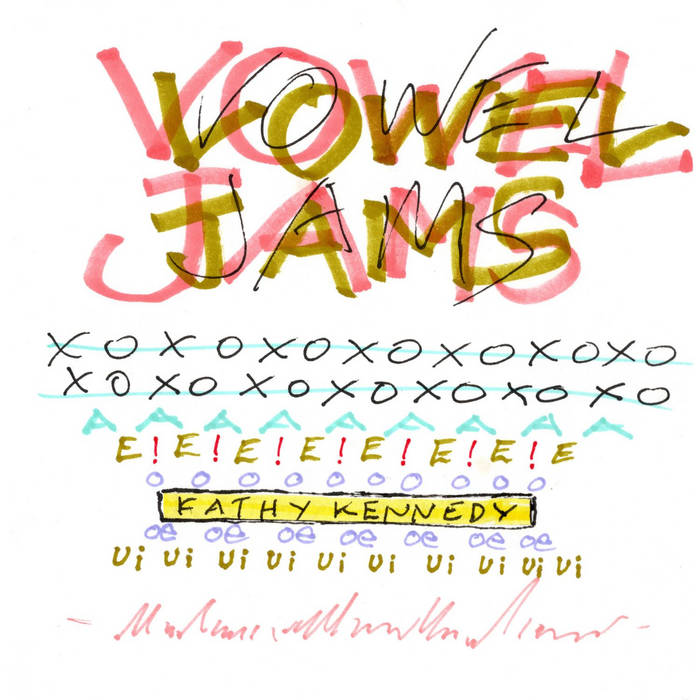

While working with others in this capacity, both her students and members of her choral groups, Ada-X and Choeur Maha, have been the main focus of her career; she has now, after many decades, released an album of her own into the world: Vowel Jams. She incorporates her training in visual art into the booklet that accompanies the download, the various vowels on which she's "jamming" transcribed with a sort of energy translated through Kennedy's use of color and penstrokes. Her understanding of sound as meditation comes through, too, as her vocalizations form complex tapestries of frequencies that vibrate through the listener's unspoken emotional lexicon over the course of the album. See? Despite her extensive knowledge, she's not all authority; there's a play element to her craft—a lightness penetrating its emotional resonance.

Kennedy and I spoke through unsteady virtual channels, eventually turning off our cameras for the bulk of the conversation so as to improve our connection. Her deftness in navigating this technological challenge was, in an odd way, the perfect introduction to this artist who has spent her career exploring the possibilities and limitations of the human voice, often translated through audio/visual systems.

Kathy: Where are you, Meredith?

Meredith: I'm in California. And you are in Montreal? I would love to hear about the scene there and how that has influenced you as an artist.

Kathy: Montreal is such a cool place. It has always been a real incubator for culture, for a variety of reasons. One, because it's one of the cheaper cities to live in. And in the '80s and '90s, it was so cheap. Nobody was encumbered by a job, and everybody sat around in cafes and looked beautiful and talked about poetry and politics and so on. It's also a real hotbed for new media, and has been so for a while. I'm not sure why. And also, Montreal has been a real hotbed for contemporary dance. I think it's because we have two languages and the influx of people from many different countries. It's a port city, as well. There's always been a lot going on in Montreal. It's really the cultural capital of Canada: 'CCC.'

Meredith: It seems like, within Montreal, you've been involved in creating some community-based organizations as well, Ada-X and Choeur Maha.

Kathy: In the '90s, up until very recently, that's been the main thrust of my artistic practice: creating community. And that has somewhat of an effect on the nature of what I make. I've been interested in engaging with the greater public, trying to entice the everyday pedestrian to appreciate contemporary art, so a lot of what I have done has been outside of concert halls, outside of venues—literally outside. I have so much to be thankful for in creating these communities, but it does have certain limitations in terms of individual expression. Many a time, I have not followed my own vision in order to serve the group, and in order to please the biggest public possible, and so with the launch of my retrospective book [Singing Off the Grid], that kind of put a bow on what I've been really committed to doing in the last 20 or 30 years. I said to myself, it's now or never to make the music that just pleases me.

Simultaneously, I've been trying to do these large-scale performative works for the greater public. But at the same time, I've been involved in the underground improv scene for a very small audience. I don't know how that public is going to respond to these pieces [in Vowel Jams], because they're about groove, which has always been an important thing. So I just chose to say, "The hell with it. I'm gonna do what I want to do," and sometimes it's going to sound kind of funky, kind of R&B, maybe pop-ish, with some melody, some sing-along ability. Sometimes I feel like it might displease everybody that I've been trying to approach. And it might please everybody a little bit. Either way, I'm just going to do it.

Meredith: I think that that's refreshing. It seems like everything's for the algorithm now, you know? There's this trying to please everybody and reduce things. So to go against that, I think, is maybe something that we need in this moment.

Kathy: So much so. And the genre thing, I just have no patience or time for fitting into whatever genre the internet bodies need to put me into. I just can't be bothered.

Meredith: "Fostering environments for others to sing in" is part of your practice. You've talked about taking things outside the concert halls, physically. What makes a space an ideal environment for others to sing in?

Kathy: A number of things. The first would be their psychoacoustic properties: whether it's good for singing or not. Outdoor singing is not obvious, because of the—(wait for it, I teach electroacoustics)—because of the coefficient of absorption, which means when there's open space, the sound just flies out. It has nothing to bounce off of. So it's important to choose a space with some walls, so it can kind of catch and reflect the sound. So the first thing is the acoustic properties, and the second thing would be the meaning, the socio-political meaning, of that place. When I do a piece outdoors, it's very much about giving voice to the individual in public space.

Meredith: I love that. And that has some political implications as well?

Kathy: Absolutely.

Meredith: Tell me about that.

Kathy: Well, that's it. Very much so. And I'm also really interested in surrounding an audience and giving them, first of all, a more than stereophonic experience in which they can navigate the sound however they see fit. So the shorthand for that is 'immersion'. I'm really interested in giving an immersive experience. And another really important thing for me about those works is in broadening the aural or sonic horizons. I grew up in a very rural place with a very good listening environment, that is, it was near water and mountains, so there was natural reverberation. Where I grew up was like a natural amphitheater. And when I first moved into the city, I realized we can't hear very far away because of noise pollution and the way buildings buffer and mask sound through urban noise. I've been really interested in acoustic ecology all throughout my practice. So these works I've made over the years are large-scale and usually involve a large physical space. For me, it hopefully opens up people's listening and tunes them into their natural environment, just by being able to connect with sounds that are more than 50 meters away, 50 feet away.

I use pirate radio to connect people by transmitting musical accompaniment and having singers or performers pick it up on boom boxes or other kinds of portable radio they bring. Pirate radio, of course, has all kinds of political overtones. It is literally about taking media into one's own hands.

One of my favorite performances was on International Women's Day. I think it was '93 or '94. My women's choir and I went to a few sites, famous sites of patriarchy in our city. Those were City Hall, Notre-Dame Cathedral, and Hydro-Québec, which had a lot of power in many ways. Twenty or more singers just walked into these buildings playing a soundtrack that was very soothing and calming, with strings and violins, and the women were singing wordless melodies over them. We were, by our definition, infusing these sites of patriarchy with a feminine presence.

What I felt was so beautiful about it was that, with radio, you're all connected. It's not linear. It's not hierarchical. There's no obvious leader. They're just moving in a fluid manner, like a flock of birds or something. And it was really troubling to some of the officials in these spaces to see this. That is what is so interesting: to see these individuals in an allegedly public space making beautiful, personal, intimate sounds. And they wanted to accuse us of disturbing the peace, of course. Everybody could see we were just beautifying the space and, in fact, making everything quieter, because everybody was suddenly intent on listening to these beautiful sounds.

The other thing that I love about pirate radio is that instead of the traditional technology of one loudspeaker system of two speakers on either side that have to be super loud, the power is spread out among the individuals, and no one is loud, but together, just like in the natural world, with animals—like crickets, for example, with many small satellites—you can make even more noise than you can with one very powerful set of speakers. And I think that's just such a beautiful thing.

Meredith: That's so interesting. They were in there accusing you of disturbing the peace when you were bringing the peace. You were embodying the peace.

Kathy: Yeah.

Meredith: So you describe what you do as "vocal composition for personal pleasure"—or at least on this album, maybe. I am curious about the most pleasurable parts of composing this album.

Kathy: I think what I love most about it is that I treated the tracks like a sketchbook, very much like the visual art model, where I just put some new tracks on every other day. And at some point, I had something like 40 tracks, and I'd just take some out, put them back in. Just keep at it, like I would a painting. I don't know if everyone works like that—it doesn't feel like that in the musical world. Certainly, when working with technology, there is a tremendous bias toward being organized. The technology can force you out of flexibility. Being forced, in multi-track apps, to decide on a key, tempo, and all that, is always the challenge for me: not to get locked into what the technology expects me to do. And I think that I managed to break out of that, so I'm really happy with that.

Meredith: That's good. So you were playing against the constrictions of the DAW. Nice.

Kathy: I like that. "The Tyranny of the DAW."

Meredith: Is there anything else that you would like to share?

Kathy: I have a news flash, and you didn't ask because you didn't know, but in the last week, somehow, I have sequestered five fabulous videos to accompany these pieces, because they're not that easy to perform live. I did have an opportunity to perform recently, and thought, "Oh, I'm going to be so boring," but I've sequestered some video work from my fabulous community, and we will put them on the Bandcamp link. They're just great.

Meredith: That's exciting. And you're not releasing physical media other than the book with this. Can you speak a little bit about that decision?

Kathy: What do you think, Meredith? Am I doing the right thing? I just don't have a CD player myself, you know, so I chose not to make a CD. Maybe I should, though.

Meredith: There are a lot of reasons not to, for sure, and it's something that you can always change. You can always go back and release a CD at some point. But I think your approach is interesting.

Kathy: Yeah. If people want a CD from me, I will make it for them.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmJonah Evans

The TonearmJonah Evans

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments