Joane Hétu has spent more than four decades carving out her territory in Montreal's experimental music scene. The composer, saxophonist, and vocalist emerged in the early 1980s as a founding member of avant-pop groups like Wondeur Brass, Justine, and Les Poules, where she helped forge a distinctly Québécois interpretation of contemporary music. Her approach merged the pluralist ethos of New York's downtown scene with European progressive sensibilities, all while maintaining roots in Quebec's cultural soil.

Since those formative years, Hétu has become one of Canada's most important figures in musique actuelle. She co-founded SuperMusique in 1980 and has served as its artistic co-director since 1998, nurturing generations of experimental musicians through her commitment to inter-generational collaboration. Her own compositional work spans everything from intimate vocal pieces to large ensemble works, consistently exploring the space between composition and improvisation. As founder and longtime president of the DAME record label, she has also played a crucial curatorial role in documenting Canadian experimental music for over three decades.

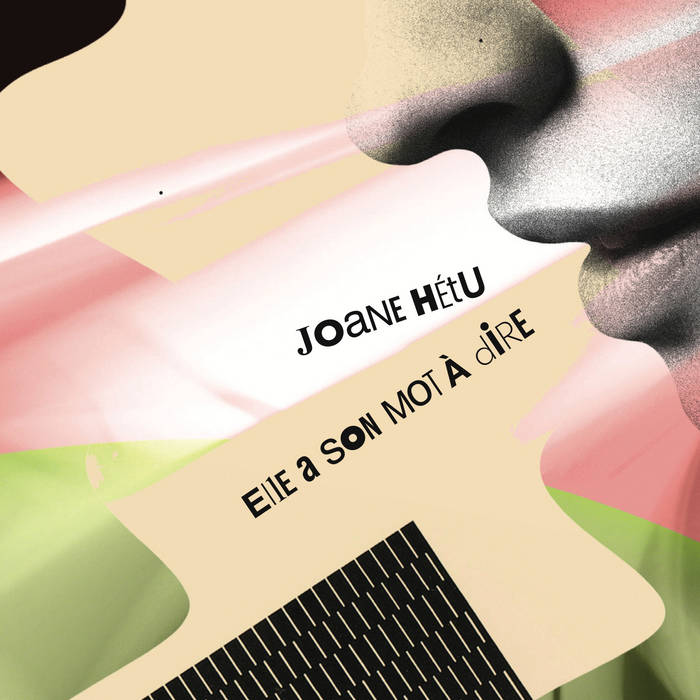

Her latest release, Elle a son mot à dire, captures Hétu leading Ensemble SuperMusique through thirteen of her pieces—most of them new compositions alongside select revisited works from earlier periods. The album demonstrates her continued resistance to artistic pigeon-holing, moving fluidly between ambient textures, quasi-operatic vocal explorations, and abstract instrumental dialogues. At sixty-six, Hétu remains as committed as ever to challenging listeners while maintaining the deep collaborative relationships that have defined her artistic practice.

This interview is translated from the original French.

Lawrence Peryer: In your work with Wondeur Brass, Justine, and Les Poules in the 1980s, you helped create a distinctly Québécois interpretation of experimental music by merging downtown NYC aesthetics with European prog sensibilities. What was that like?

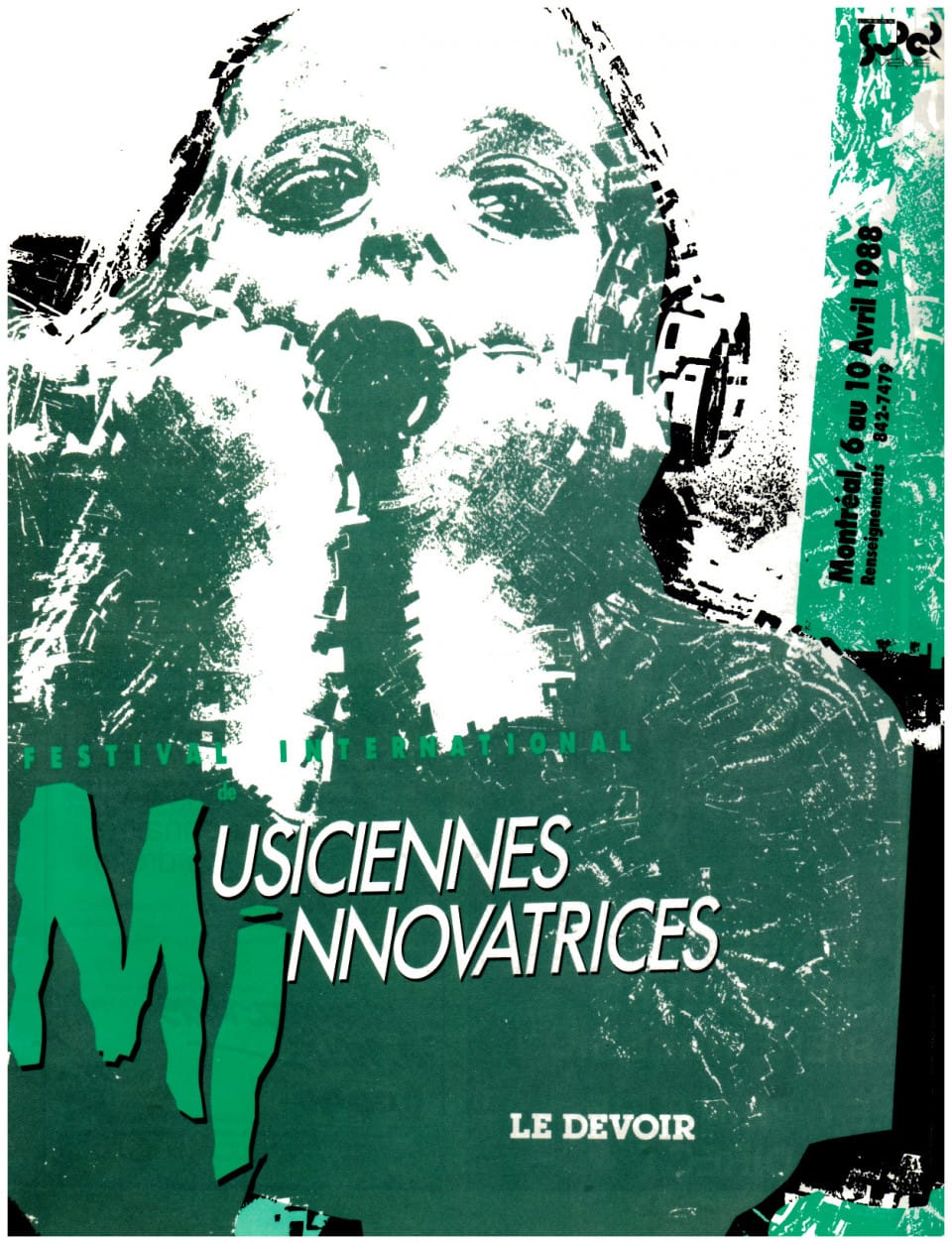

Joane Hétu: I was very young, in my twenties, and this fusion happened quite instinctively, without real premeditation. We were connected to the New York scene—Zeena Parkins, Ikue Mori, and Fred Frith—and through the Recommended Records network, notably with Chris Cutler. With Danielle Palardy Roger and Diane Labrosse, we founded the SuperMusique organization in 1980. In 1988, we organized a Festival of Innovative Women Musicians, entirely devoted to women's groups working in avant-garde music.

Lawrence: What prompted your shift from avant-pop toward deeper exploration of improvisation and composition? And how has the Montreal experimental music scene changed over these four decades?

Joane: Improvisation imposed itself on my approach in the early 1990s. In 1992, Jean Derome and I founded Nous perçons les oreilles, a group exploring both song and radical improvisation. But I never stopped writing or composing. These practices have always coexisted in my musical universe, in a constant state of interaction.

In forty years, the new music scene—contemporary, experimental, or whatever term one prefers—has undergone enormous changes. Today, it brings together artists from the ages of twenty to seventy and unfolds in numerous venues, both in Montreal and in the regions. Despite significant challenges, particularly financial ones, I find it in good health. The audience is faithful, and new curious people venture into it regularly.

Lawrence: Your vocal work employs unconventional techniques alongside traditional instruments. How do you approach the voice as an instrument, and how does this connect to your work with the noise choir JOKER?

Joane: I never learned to sing. My influences include artists such as Tenko, Phil Minton, Jaap Blonk, and Paul Dutton. I learned the saxophone, but I always kept my own way of playing it. I have a deep love for the voice and its noise-making potential. It's visceral and fundamental to me.

What pleases me is this cohabitation between writing and improvisation, the freedom offered to interpreters, and their active engagement in creation. This applies to both my solo work and collective projects, such as JOKER.

Lawrence: In pieces like "Elle n'est pas un animal" and "Mot elle a," there's a fascinating interplay between structure and freedom. How do you balance composition with improvisation?

Joane: I adore this tension between composition and improvisation. I like to see them coexist, respond to each other. Graphic scores allow precisely this encounter. "Elle n'est pas un animal" is a good example: the piece rests on a clear concept, a guiding thread, while integrating random elements and suggested materials. It's improvised but structured. I love it deeply; I was very moved while composing it.

In "Mot elle a," the singer's part is written, while the percussionist's part is improvised from instructions. The piece remains flexible, malleable, depending on the interpretation. For now, I only have one recording, but I hope it will live through other recordings and interpretations. This is, moreover, one of the objectives of open scores: to encourage multiple and living interpretations.

Lawrence: You wear many hats—composer, performer, ensemble leader, label head. And in your work with Ensemble SuperMusique, you've consistently brought together musicians across generations. How do you handle these different roles, and what value do you find in these inter-generational situations?

Joane: I'm a person with multiple functions: artist, cultural worker, manager, choir director (Chorale Joker, founded in 2012), artistic co-director of Ensemble SuperMusique since 1998 with Danielle Palardy Roger. This is, in my view, a characteristic of contemporary music. The composer is often also a performer, improviser, ensemble leader, and manager. I like each of these roles, even if the manager role pleases me a bit less. This balance between functions nourishes me.

Ensemble SuperMusique's mission is to welcome emerging artists, mid-career artists, and major figures alike. This intergenerational cohabitation is a great richness for us. It opens perspectives, stimulates listening, and provokes essential exchanges.

Lawrence: You've explored the concept of "territory" extensively, particularly in La femme territoire ou 21 fragments d'humus. Your winter trilogy also seems to have been a significant creative exploration. How do these thematic works function in your compositional practice?

Joane: La femme territoire ou 21 fragments d'humus is a very important work for me. In it, I take a position, as a woman, on my territory—intimate and collective. I doubted while writing it; I had trouble trusting myself. But today, I'm happy with the path traveled and with this work.

With my trilogy Musique d'hiver, I covered this season musically. I still love winter, but I no longer feel the need to translate it into music. Neither winter nor any other season, for that matter.

Lawrence: Elle a son mot à dire draws from compositions spanning over two decades. How do you see your older pieces in relation to your newest work?

Joane: I don't yet have a global vision of my work. I respond to the call, to the impulse of the moment. I am still, fundamentally, the same composer. I have just as much affection for my pieces from the 1980s as I do for those from the 2000s. I try to keep them alive in me, to maintain them like one does with old plants.

Lawrence: Your work with DAME has helped document an important chapter of Canadian experimental music. What motivated you to take on this curatorial role, and how do you reflect on it now?

Joane: Good question. What pushed me to get into all that? I've always had a passion for sound recording. From 1985, I got involved in Ambiances Magnétiques, then DAME took over. After my daughter's birth in 1990, I was looking for a certain stability, knowing that tours would be more difficult. Naively, I believed that having a record label would offer a form of security. It was quite the opposite. This enterprise cost me a lot in creative time. Looking back, it's perhaps what I regret most: having carried it for so long, for thirty-three years.

Lawrence: How do you see the relationship between artistic innovation and audience accessibility in your work?

Joane: I believe the public has the capacity to welcome innovation. But it needs tools, which are becoming scarce: radio broadcasting, interviews, production support, and venues dedicated to new music. All of this would help contemporary music meet the open ears that exist—I'm certain of it.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments