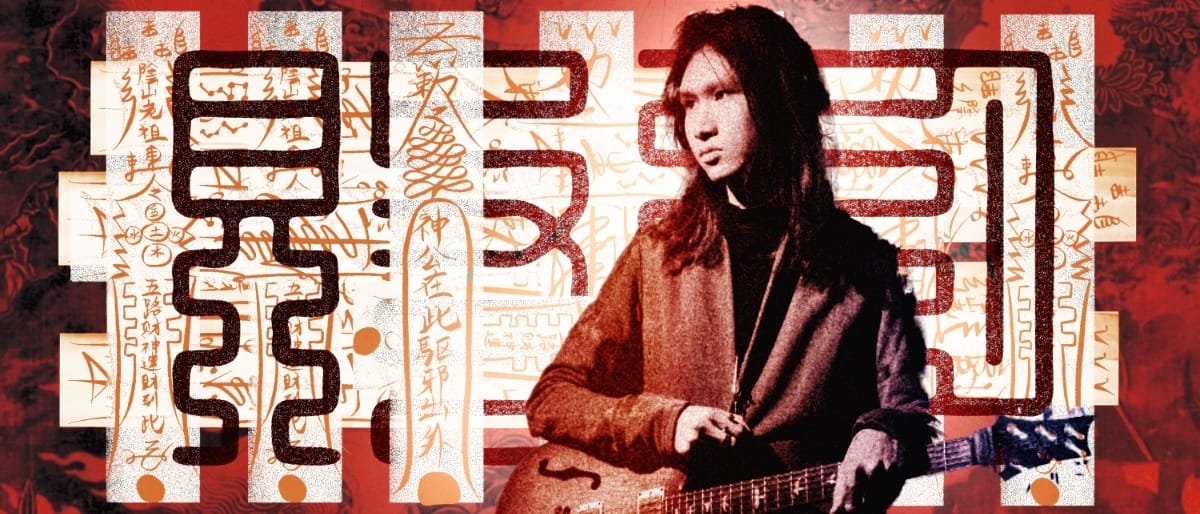

Most heavy music gets its weight from volume and distortion, but Lingyuan Yang found a different way. His quarter-tone guitar creates an unsettling heaviness through the friction between microtonal intervals and conventional piano tuning. This technique generates ferocity through harmonic complexity rather than sheer force, reflecting his generation’s relationship to musical tradition. Yang, born in 2001, grew up with access to music from around the world, absorbing influences from Chinese traditional music, metal, and classical composition with equal facility. After studying with experimental music luminaries like Peter Evans, Eric Wubbels, and Anna Webber at The New School, Yang developed a compositional voice that honors his cultural background while prioritizing experimentation.

These influences come together on Cursed Month, Yang's debut album recorded just before he left New York for graduate studies in the Netherlands. The timing wasn't accidental—Yang wanted to document the musical chemistry he'd developed over three years of workshopping with pianist Shinya Lin and drummer Asher Herzog, feeling that their collective exploration had reached its peak intensity. The album's title draws from Chinese astrology, where each zodiac animal corresponds to an inauspicious month for birth, times that ‘teem with violent youthful fervour.' For Yang, this concept of 'cursed time' works as a framework and a metaphor for the risky path of experimental music. Choosing to reject mainstream expectations requires what he calls "intense, sometimes chaotic drive."

The album's release on Chaospace Records adds significance to Yang's story. The label emerged from recognition that Asian artists in New York's experimental scene were scattered and isolated, lacking the mentorship networks that other communities took for granted. Yang's connection to this initiative mirrors similar experimental music movements as artists hone their craft while building the infrastructure to support voices that might otherwise remain unheard. Cursed Month captures the sound of a generation finding new ways to honor their backgrounds and transform the music around them.

Lawrence Peryer: Cursed Month marks your debut release as a leader, recorded just before you left New York for the Netherlands. Why did you need to document this particular music at that moment?

Lingyuan: There was a real sense of urgency because I knew I was about to leave the New York scene, which had shaped so much of my musical identity. The trio and I had been workshopping and revising this music continuously between 2021 and 2024, gradually pushing the material to its limits. By the time I was preparing to leave, the chemistry felt electric, and the pieces had reached a level of precision and intensity we wanted to capture. Recording Cursed Month wasn't just about making an album—it was about preserving a snapshot of years of collective exploration at a crucial turning point in my artistic life.

Lawrence: How did you first connect with Shinya Lin and Asher Herzog, and what made you know this was the right trio for these compositions?

Lingyuan: I first met Shinya through our mutual mentor, Peter Evans. After a session together, I was amazed by Shinya's ferocious improvisational style and his ability to sight-read incredibly complex material with ease. It immediately felt like a perfect match for the kind of music I was writing. I met Asher through a Chaospace-organized concert called Controlled Chaotic, where we each played different sets. We were impressed by each other's playing and felt a strong artistic connection. From there, it was clear that the three of us shared a similar intensity and approach, which made this trio the right vehicle for these compositions.

Lawrence: What specific qualities in each of their playing styles made them essential for realizing these pieces, and how did you develop the trio's unique role distribution?

Lingyuan: Asher has his own band, Porcelain Vivisection, which plays in a punk and hardcore style, and he's also active in the improvised music scene. He can deliver aggressive riffs while improvising seamlessly within complex rhythms, which makes him a perfect fit for this trio. In many sections, I needed him to play intense, precise rhythms in very tricky spots—for example, in "Ritual Fire," he has to perform blast beats through rapidly shifting meters, such as 15/16 to 7/16 to 5/8. That kind of control and ferocity is extremely demanding.

During the writing and rehearsal process, we discovered that letting Shinya's piano handle much of the low-end created a powerful, grounded foundation, while it freed me up on guitar to focus on percussive attacks and microtonal lines. This distribution allowed each instrument to occupy its own space without competing sonically. I've always loved the piano's low register—its rich overtones and metallic timbre felt perfectly suited to the mood of the music we were creating. Through workshops and experimenting with different textures, we realized that having the piano carry the bass opened up the overall sound, giving more room for the guitar's unconventional harmonies and rhythmic gestures to cut through clearly.

Lawrence: How does the concept of ‘cursed time’ that the album title refers to connect to your experience as a young experimental artist?

Lingyuan: In some traditions and superstitions, 'cursed time' is seen as unsettling and unlucky, and people might even seek out shamans to try to change their fate. Through this album, I wanted to express that sense of unease and instability through music instead. As a young artist, choosing to reject mainstream music and dedicate myself to boundary-pushing work is a risky path. The concept of 'cursed time' felt like a fitting metaphor for the instability and uncertainty that comes with that choice. It reflects the intense, sometimes chaotic drive required to pursue experimental music outside of what most audiences expect or find comfortable.

Lawrence: Like many of your generation, you have a wide and varied range of musical interests. How has this affected your experimentation with new forms while honoring Chinese cultural elements?

Lingyuan: I grew up listening to all kinds of music, from classical to metal, and that wide exposure early on made me comfortable moving across genres and combining different sonic ideas. I've also always been drawn to Chinese traditional music and culture. Even though this album doesn't directly incorporate traditional Chinese instruments or melodies, its concept is deeply rooted in Chinese culture: I used the idea of the Chinese zodiac and its associated fortune-telling as the thematic inspiration for the compositions. This approach let me explore something new musically while still honoring a cultural perspective that feels personal and meaningful to me.

Lawrence: Quarter-tone guitar sits at the heart of your sound, yet you avoid the overdriven tones typically associated with heavy music. Can you walk me through your thinking about using microtonality for intensity rather than distortion?

Lingyuan: When combining 24-EDO—or quarter-tone tuning—with a piano tuned in 12-TET, the notes outside the standard twelve pitches often create a strong sense of tension and unease. Quarter-tones also appear in the natural harmonic series, like the eleventh harmonic, and I sometimes use quarter-tones derived from these natural overtones, while other times I deliberately use quarter-tones outside the harmonic series to create a sense of tension and release.

As for distortion, I'm not a guitarist who prefers overdriven tones. I believe heaviness comes from the playing itself, not just the sound. Using a clean tone makes the quarter-tone harmonies much clearer, which enhances the tension created by these microtonal intervals. It allows the harmonic complexity to really speak, adding intensity without relying on distortion.

Lawrence: Your work with JACK Quartet employs Just Intonation, while this trio explores quarter-tones. How do you understand different tuning systems as compositional tools, and what draws you to work outside twelve-tone equal temperament?

Lingyuan: My two string quartet works were each based on distinct concepts of microtonality. The Heart of Ge'Nyen was composed around the spectral analysis of a cello snap-pizzicato, and the entire piece unfolds using the harmonic series derived from that single sound. Interference focuses on the fourteenth and fifteenth harmonics and their integer multiples in the harmonic series. Since both pieces are grounded in harmonics, using Just Intonation came naturally as it allowed me to precisely align the pitches with the natural overtone relationships.

In contrast, for this trio, I used quarter-tones to increase tension and enrich the harmonic palette in a way that felt right for the material. I'm drawn to microtonality because I find the harmonic possibilities of twelve-tone equal temperament increasingly limiting. Exploring microtonal tunings opens up new expressive colors, lets me create more fluid and unexpected harmonic relationships, and gives me tools to evoke sensations of tension, ambiguity, and release that aren't possible within conventional tuning.

Lawrence: How did your mentors at The New School—particularly Eric Wubbels, Anna Webber, and Peter Evans—influence your thinking about what music could be, and how did your collaboration with Joe Morris from a different generation add to that foundation?

Lingyuan: Each of my mentors had their distinct approach, and I tried to absorb their guidance and synthesize it into my own musical language. For instance, with Eric and Anna, my focus was mainly on composition, especially exploring microtonality and the theory behind just intonation, which fundamentally expanded how I thought about harmony and pitch relationships. With Peter, our work centered more on improvisation, and I learned a lot from his fearless, exploratory mindset and the way he approaches spontaneous music-making as a dynamic, living process.

Joe Morris was incredibly supportive of me, especially when I first started experimenting with adding unusual electronics to my guitar playing. He encouraged me to explore those ideas, many of which eventually developed into the effects I use on this album. Joe is also a wonderful teacher—he has a deep understanding of improvised music and an open-minded approach that makes you feel free to take risks. He was really my introduction to improvised music; we would often improvise together for an hour straight, and through those sessions, I learned so much about listening, reacting, and staying present in the moment. Working with someone from a different generation who has such a wealth of experience helped me grow tremendously as an artist.

Lawrence: Can you describe your approach to live electronics and how your compositional process evolved during the development of these pieces?

Lingyuan: All of my live electronics are created using Ableton and Max. In some sections of the compositions, I wrote detailed parameters into the score—for example, applying ring modulation to the piano or creating feedback textures that involve the entire band's sound. But most of the time, I use electronics improvisationally to shape and expand my guitar sound in real time. I also use them to add rhythmic elements by controlling LFOs or triggering effects, which helps me create richer textures and more dynamic interplay within the trio.

I actually wrote out all seven pieces quite early on. Each one was based around a specific compositional technique I learned from studying Brian Ferneyhough, using generated numerical sequences to create rhythmic structures, which is how most of the rhythmic material across these pieces came to life. Over time, through continuous workshops with the musicians, I kept refining the details of each piece, adjusting the phrasing, dynamics, and timing to better fit the trio's chemistry.

Lawrence: Chaospace Records, which releases this album, encourages Asian artists through mentorship. How has working within this community influenced your art?

Lingyuan: Chaospace has contributed a lot to the presence of Asian artists in New York's new music scene, where we're often underrepresented and scattered. By organizing events and creating opportunities for us to meet and collaborate, Chaospace helped build a sense of community among Asian musicians and artists. Asian artists also face many unique challenges, and being part of this collective made me feel less isolated. It gave me a support network and a space to share ideas, which has been really important for my artistic growth.

Lawrence: You hold a BFA from The New School and are about to pursue composition studies at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague. What draws you to formal European conservatory training, and do you think you'll find dramatic differences in how microtonality is taught there versus your experiences in New York?

Lingyuan: I wanted to explore the European new music scene, which has always interested me. Many of the composers who have influenced my thinking, like Iannis Xenakis, Helmut Lachenmann, and Gérard Grisey, come from this tradition, and I felt studying in Europe would give me a chance to engage with these ideas more closely. I also chose the Royal Conservatoire The Hague because it has a strong program in electronic music, and I wanted to further develop my electronic music skills alongside my compositional work. I'm excited about the rigorous academic environment, which I think will help me learn new things and expand my musical perspective.

Based on my time in New York and my studies with different composers, I've already seen how individual musicians have very personal views on microtonality. For example, when I studied with Chris Otto, he preferred not to simplify Just Intonation notation, believing in maintaining full accuracy. In contrast, Eric Wubbels suggested that I could adapt and replace complex accidentals as needed for practical reasons. I'm curious to see how European composers and teachers approach these questions and what new possibilities their perspectives might open up for my own work.

Lawrence: Your piece "Yin-Yang" for wind and string quartet premiered this past April. How does writing for these more traditional chamber ensembles relate to your work with the electric trio?

Lingyuan: "Yin-Yang" is a piece where I explored harmonies created by combining the harmonic series and the subharmonic series. Writing for a traditional chamber ensemble like a wind and string quartet required me to think carefully about each instrument's characteristics and playability, which meant I spent a lot of time on orchestration and balancing the ensemble. In contrast, working with the electric trio gives me the freedom to realize more wild compositional ideas and exaggerated electronic sounds without worrying as much about traditional instrumental limitations. Each setting challenges me in different ways and lets me develop different aspects of my musical voice.

Lawrence: With Cursed Month now complete, what's the next project?

Lingyuan: I'm currently working on a new piece that I'm really excited to bring to life. For this project, I've written several different Just Intonation tuning systems, each creating harmonies that feel almost otherworldly. There will also be a greater emphasis on electronics, and, of course, improvisation will remain an important part of the music. I'm eager to keep exploring how these elements can interact in unexpected ways and push my sound even further.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmChaz Underriner

Comments