My discovery of West Virginia Snake Handler Revival "They Shall Take Up Serpents" was not because I was jonesing for Hani Polyphonic Singing in Yunnan, China, or Gyil Music of Ghana's Upper West Region. Nope, though the label Sublime Frequencies has those titles and some 200 more global music wonders, and that's where I learned of this record. Alan and Richard Bishop, brothers and bandmates in the late and very great Sun City Girls, founded the imprint with Hisham Mayet in 2003. This is the label's first American music release, and producer Ian Brennan explained this and more in our mid-November video chat. With Ian's approval, future references to the record will be as Snake Handlers.

As a Christian from the American South, I noticed that in polite circles folks would gently change subjects to cotillion or SEC football if whispers about backwoods churches where supposed snake handling took place were brought up. Please pour me another bourbon, Elizabeth. We say grace, we say ma'am. In other circles, including my time in the Assemblies of God—more as an observer than an enthused participant in American Pentecostal handwaving, dancing, and speaking in tongues—the snake handlers were considered to be fools. Or at least foolish. Keep in mind, Little Richard, Elvis, and Jerry Lee were all brought up in the Assemblies of God. It mattered. Keep a picture of the exit door.

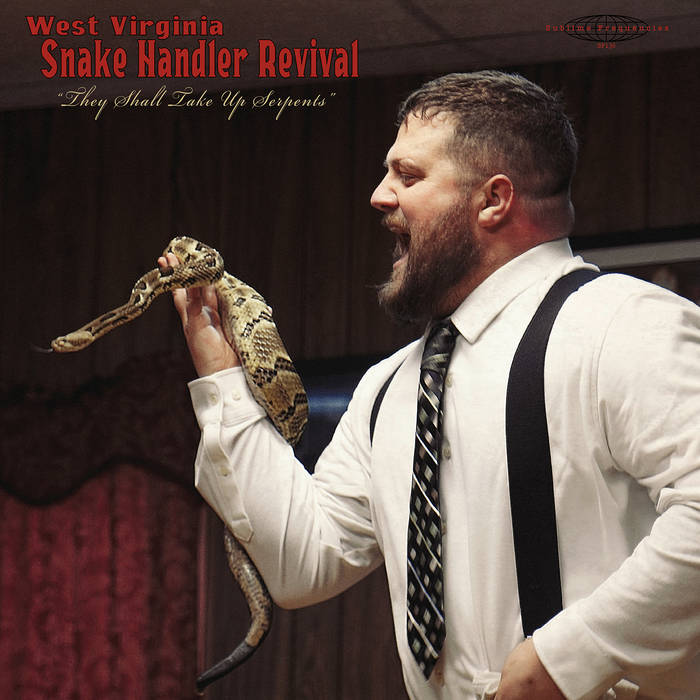

Snake Handlers is an audio-only recording of a remote West Virginia church service led by an exuberant preacher fronting what may be the truest rock and roll music ever. Sit with that hyperbole or raise your hands and stomp your feet. The four-piece band consisting of guitars, bass, and "a bonnet-wearing senior [who] whacked away at a trap kit that dwarfed her" is fire. Purifying fire. Holy Ghost fire. The sort of fire Flannery O'Connor largely extinguished across her stories as that fire was short of the grace she brought to bear in such tales as "The Enduring Chill." A couple of titles from Snake Handlers: "Rock and Roll Was Stolen from God by Satan" and "Don't Worry, It's Just a Snakebite (What Has Happened to This Generation?)."

Snake Handlers defies disengagement. If your listening tastes include bands colliding and collapsing into la historia de la música rock, you like the repetition of the Velvet Underground or The Fall, this record will likely hip-shake existing presumptions concerning freedom.

Here follows my conversation with Ian referencing our brief introductory and adieu emails, edited for clarity and length. But forewarned is forearmed; we did get down into some hollers and up to the hills, and irony wasn't anywhere to be found.

Steven Garnett: You noted in your email to me that your goal is to bring the listener to the musicians, not the other way around. Your discography—more often documenting music outside the US—is abundant proof that you have delivered on your goal and will continue to do so. With Snake Handlers, you brought American music listeners, especially American music listeners, to an underknown American music. You likened it to tracing a line between the Parchman Prison Prayer recording and Africatown, AL, as well. Can you elaborate further on the somewhat recent choice to really lean into American music?

Ian Brennan: I don't know if it's a choice, as oftentimes I have a list of ideas, and some of those things have never been done or gotten to, and other things that are newer happen pretty quickly. In the case of Parchman, the idea had been in the works for many years pre-COVID, but the old administration was not receptive. They said no. Then COVID happened, which obviously made it impossible even if they had said yes. These things take different turns. But we—Marlena Umuhoza Delli, my wife, who does all the video and photos in most cases—we started doing work with disenfranchised people in America and around the world more than almost two decades ago.

After a while, it was like, yes, there are underserved and underrepresented populations in places that are largely ignored by mass media globally, like Comoros or Suriname, or, really, most countries, in most languages. But those marginalized people also exist in the world's biggest economy. That led to working with unhoused and disabled communities os. My sister, Jane, who passed away earlier this year, was developmentally disabled, and we did a record with her community right before COVID.

Coincidentally, with the snake handlers, it was very much about looking at the other side of this coin of tradition. I think people outside the South in America have a lot of exposure to ideas about what the South might be, but obviously deny its complexity. Stereotypes are what is largely fed. There's great diversity in the region, and it's a huge region physically, and it's a very complex region.

I think back to Italy, and how they told me that with traditional music, oftentimes it was clan-based because the tuning would be different for each family. So even if they made the journey down from a mountain valley and went back up to the other mountain valley, which in those days was probably a one-day journey, they couldn't play with the other people because they tuned differently, like by probably a microstep or a half step.

I think Appalachia's maybe the best example of that. Still, reaching this area is not possible a lot of times when it has had heavy snow. When I was returning from the recording itself, the GPS kept turning me onto dirt roads. It was just doing that thing where it [GPS] thought it was better somehow, like it was an eighth of a mile shorter or something. So I was getting increasingly close to maybe not making my flight. These are remote areas.

But for me, with the Snake Handlers record, and I think the Parchman Prison Prayer records, my bias would be that I probably had more sympathy for the Parchman story and for the artists and that tradition. But, after the last election, I really felt it was necessary to try to understand some of the roots of this disenfranchisement. When doing the research, something that I didn't know really was how much snake handling had been made illegal or discouraged, and looked down upon: the white church traditions of the poor whites. It was also seen as being vulgar, almost immoral in some cases, because of its boisterousness, its expressiveness, and its emotionality.

Garnett: You got me thinking. My father is from rural New Hampshire, and my mother is a native of Jacksonville, Florida. Trace both of their lines, and you get to impoverished Scots-Irish people, which I think is what you're talking about with ostensibly what Appalachia is. Books have been written about Appalachian culture and temperament. Just as the music might be raw, these were the people who the town sheriff probably had to haul into jail every Saturday night for drunkenness and bar fights. Not saying my people were that, but maybe a few of them fit the bill.

I think about this sort of primitive—or we call it primitive—turn-of-the-century Holiness experience in the United States, 1915, and the Assemblies of God is emerging in Los Angeles. The Pentecostal movement has legs, and many Black churches, of course, also practiced forms of ecstatic worship.

My next thought is, "Why should the devil have all the good music?" There's something about the freedom in this music and worshiping that is exciting, I think, to anybody who gets to hear it.

Ian: I think that movement in the early twentieth century undoubtedly had something to do with a response to the Industrial Age and the changes. The pastor even says in this case, "This was our music. It was stolen from us. Rock and roll was stolen from us by Satan." It's never going to be that simple, and it's never going to be that clean and cut and dried. The first snake-handling church was in 1922. So that's officially pre–rock and roll. Not obviously roots of rock and roll, but pre–rock and roll. And it makes you wonder. I think the important thing is the complexity of it, that there was this multi-cultural coexistence, even though largely it might have been parallel, going on for hundreds and hundreds of years, really longer than anywhere else in America.

There's something to the music, and I think in a concrete way, in this case, it's something so rare to see even in other parts of the world now, which is to see musicians, meaning people who are virtuosic on an instrument. That's rare outside of the classical realm, where somebody is trained to do that. Seeing two flatpicking guitar players on Telecasters playing their asses off wasn't a big deal when I was a teenager. That was everywhere then. But now it really struck me. I was like, "Wow, you don't see that anymore."

Garnett: What you captured requires technology, but the residents of this neck of the woods are, whether minutes or miles from cell phone towers or America Online, kind of like the Amish or what remains of the Shakers or Mennonites. They seem to live in contradiction. Isolation, perhaps—isolation for which they're grateful in lieu of immersion into modern technocratic memory holing and mass cultural manipulation. These folks seem unlikely to give hot takes or to embrace causes apart from those that benefit their families and community. I think maybe it's coming from the history you already referred to, and from the separation by class and geography. But I wonder if you could detect, while you were recording the service, whether there was something—did you have a metaphysical experience, or was it all business?

Ian: I think it's moving. I feel like listening is so important because that's the only way we have a chance of understanding one another. I think the binary nature of the internet and digital technologies makes people want things to be one way or the other. They want it to be absolute. That's why there's such an intolerance to disagreement. But to understand each other, even if we disagree, is certainly the only realistic goal.

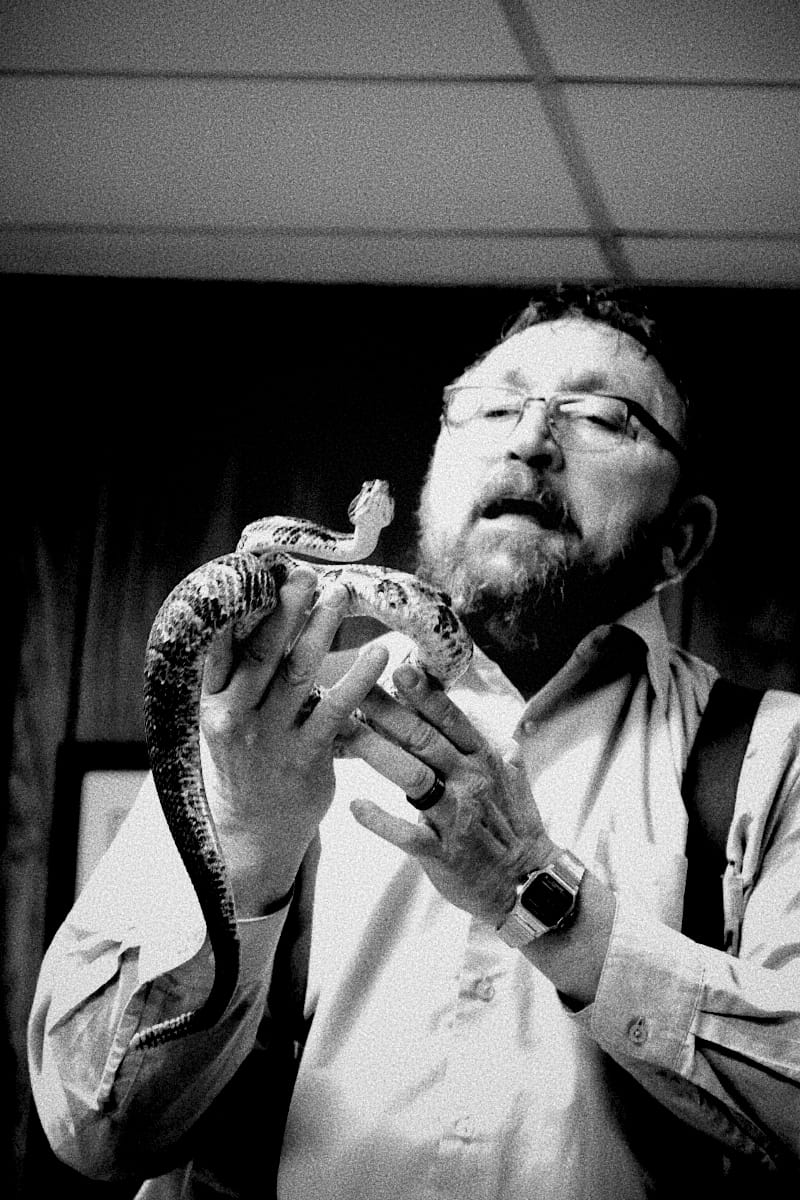

Seeing people that committed, who are putting their lives on the line because of their belief, might seem foolhardy, or however somebody might judge it. I feel like my job is to be nonjudgmental and very much to show people in their best possible light, not to put them on a pedestal, but not to look down on people at all. So this recording is not at all a judgment of the individuals. This document is just a document.

The thing that Sublime Frequencies and I agreed about was that this is trance music. That's what I felt, that they're in a trance. I saw them go into a trance, to another place, another level of consciousness. You can see it's a heightened level of consciousness. And when Sublime Frequencies heard this, they reached that same conclusion.

For me, the kind of parallel, or that correlates to some degree, was that in many ways it was more foreign to me to be there. It was a more foreign place than many places farther away, with people speaking different languages. But because I was seeing something that, in a sense, I thought I knew, there's that dissonance. I had some information about it, but there's a greater complexity there than maybe is afforded.

Photos courtesy of Ian Brennan

Garnett: Knowing that you were a young punk rocker, I get pieces of—going way back—Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, the Cramps, Flat Duo Jets, Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, the same sort of energy bursts forth from Snake Handlers. I've seen some of those performers live where the room went nuts. But maybe not a trance. The trance seems to be part of the divine search that is part and parcel of the snake handlers' service, or maybe not. But like with the Blues Explosion and the Flat Duo Jets, the room was wild. It could have caught fire. But, anyway, since you've lived the punk rock experience, what did you get from the service?

Ian: It had that feeling that I had of danger at only a few shows ever, and those were usually illegal punk rock shows in warehouses when I was a teenager. I think the difference, and this is not to take anything away from anybody, but the people that are imitating or interpreting the blues—it's a very different thing than in this case, where the musicians don't know who the Cramps are, but I think they are what the Cramps wanted to be in many ways. Meaning they're a little scary, and there is a real sense of danger in what they're doing. I think it's about commitment. When you see somebody that committed, there's an intangible element always to those things.

When somebody goes to that place, whether it's an athlete or a musician, what happens? It's very mysterious. Like, why is this person so arresting? And when it's a group playing together, I think it's even more complicated.

So I think of the Replacements. I saw them when Bob Stinson was still alive, and it was probably the best musical performance I've ever seen, and it was the worst musical performance I've ever seen. But it was the realest, and there was a chemistry that was hard to explain. Two brothers playing in this band and these four guys playing together, none of whom was virtuosic, but collectively they created something that is impossible to describe unless you experienced it.

So I think this congregation and what they do collectively is similar. I'm always interested in the voices. I believe the voice is the face of the sound. So before I went, I said to the pastor, "You are a good vocalist." And his response was basically, "Oh, I'm not a singer." And it's like, you may not be a singer, but you're a really good vocalist, which means you're a better singer than most quote-unquote singers, because there's an identity in that voice that you don't hear in most voices.

What I hear in most voices is the layers of influence, like the residuals are still there. I don't hear much of the person in most voices—corporate voices and industrial voices.

Garnett: Yes.

Ian: I do these things because I believe that the process is important and more important than the product. But on top of that, I had the idea that, okay, this is going to be valuable. There's a chance that this will work. In other words, because I know this is a good vocalist, I know that this is somebody who has something really interesting about their voice that will probably translate with pure audio rather than any visuals. And I think it's better in that sense, not to have a film of it. It's better to hear it and really concentrate on that ethereal aspect.

One thing you said that I should have addressed was just the technological aspect. I think the thing that I've seen a lot of, and I think is true in their case as well, is that it's not simply 100 percent or zero percent. It's very complex: people's relationships to technology and the ways they use technology, when they use it, and the benefits of that.

When we're recording in other parts of the world, and somebody's doing an ancient, hundreds-of-years-old music tradition, but they're using their cell phone—it's fascinating to see when it's used, when it's not used. And it's almost never going to be not at all, because increasingly people are required to. With QR codes and everything, it's almost impossible to escape phones now. It's going to be even harder in the future.

Garnett: I'm with you there. I get it.

Ian: So I think that the church folks use technology in a way that benefits them. In this case, they're using a PA. They're using electric guitars. They're using an electric bass guitar. They're using lights inside the church. There's technology being used, and they're getting there in cars. They're not getting there in some buggy.

Garnett: I am wondering about the musical setup. So was it literally a grandmother-aged drummer, two Telecasters through PA amps, and Pastor Chris letting it roll?

Ian: Yeah, and a bass player. Bass player, drummer, two Telecasters. One of them was playing through a Fender Twin. I can't remember what the other one was playing through, probably another Fender Twin. And then a pretty beat-up PA with some wireless mics. That was it. And it was loud, and thus it was very hard to record.

A veteran roots writer from the South wrote to me. I didn't send the record to him, but I guess he found out about it. He said, "I'm really happy about this record because all the recordings I ever heard of this over the years never captured it, were too clean." He wasn't responding to it like it wasn't good. He was saying that it felt raw.

Garnett: I'm thinking in terms of this quest that you have to make sure that those who are just not heard, for whatever the reasons—and probably every reason that you ascribe to them as far as economics and location and who gets to go first—are there some folks that you already have in mind to next record?

Ian: We almost never know who we're going to record. We just have faith that there will be something and somebody to record when we go to locations. And almost always—not always, but almost always—it exceeds our expectations. What happens almost without fail is that the quietest person is the one who is usually concealing the most beautiful material, the most inspired sounds, and is the most reluctant.

Many of the records we've done have been with quote-unquote amateur musicians or nonmusicians, meaning people who don't consider themselves musicians. They've never tried, have never sung publicly, maybe chorally but not solo, never written songs. And some incredible songs have been written, like instant compositions in this way, by some of these individuals that we've worked with. It's stunning.

I've been advocating for global music since I won the Grammy in 2012. I was able to go and talk to the head of awards at the time and express my concerns. I think that there's a lot of work to be done. Unfortunately, there's been little progress. But over the last five years or so, as people's interests shifted a bit with COVID and George Floyd, they've [the Grammys committee] progressed a bit. They wanted to do things, but what they've done largely just continues to create redundancy.

So, again this year, Angélique Kidjo is nominated. Anoushka Shankar is nominated. So we're talking about legacy acts. Nothing against those individuals, but you've got only fifteen or sixteen nations that have ever even won a Grammy globally. It's not true inclusion when you have 206 nations on earth. 75% of African nations have never had an artist nominated. They introduced the new African performance category, and in that category, now, I think there have been sixteen or seventeen nominees in its first three years, because some years they have more than five nominees. And still, only three countries have been represented out of fifty-six in Africa, and none of them for the first time.

It's hard to get real inclusion because there tends to be a focus on the star system. Whether it's global or folk music, people kind of gravitate toward names they know. And it's understandable that they might do that in a consumeristic way, but in a spiritual way, if people are really listening to art and music and seeking out a way to deepen their understanding of the world, I think it benefits us to seek out that which is not easy to find and that which is not necessarily easy to listen to.

I think in the age of streaming, the thing that we're really struggling with so much is that most of the best music ever recorded, most people, if they're honest, don't like it the first time they hear it. They've got to listen to it more than once. They've got to listen to it maybe even twice or three times. In the era where people were buying music, you were forced, like, "I spent this eight bucks or this twelve bucks for this album, so I'm going to try to like it. I'm probably going to listen to this record over and over again." You're not going to listen to it for thirty seconds and make a judgment about an entire catalog of an artist, especially with difficult, challenging music. And you think about something like Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz, where it's one tune, it's almost forty minutes long. That doesn't translate in the streaming era. Ultimately, it's the listeners who lose out. I think everybody loses out, but it's the listeners more than the artists who are losing out because of this.

It's that fake diversity that I think is so problematic. That is detrimental to our spiritual and mental health, not to have diverse sounds. There are no pointed fingers beyond the corporations. The corporations are the ones that are making people passive in this process. And unfortunately, they did it before through scarcity, controlling what you could hear. Now they're doing it through the opposite, through the excess, where there's so much out there, they, again, are largely in control of what most people can hear because no one has the time, and no one can listen to everything that's released when you have over one hundred thousand songs uploaded to Spotify daily. Nobody can listen to that, not even a professional.

It's really like a casino in Las Vegas. The corporations are holding all the cards now. And again, I think it's the listeners who are cheated, because I believe most people want to hear good music, care about stories, and want to see good films. But they don't really have the opportunity or the time to be active in the process, as active as you are or as most diehard music lovers are, which is always a core of people around the world and always will be. But I think the average person is instead subjected to music, to an art, that just isn't as strong and as enriching spiritually as it could be. And that's a bit of a tragedy.

In an email coda, I asked Ian if he'd consider recording a 7:30 a.m. service at my small Episcopal church. My thinking, my pitch, was what I consider to be the treasure of "slow worship." I described a contemplative space, not quite 100 years old, a small but gifted choir and Juilliard educated organist, a homily centering on the Gospel, existing outside of political camps, and the gradual illumination of stained glass as the sun rose. All was presented in contrast to both Snake Handlers and America's (hell, the wide world's) fixation on better, faster, stronger, and I win! His generous response in keeping with his worldview was, "Yes, the slow worship and de-politicized services seem like a very valuable thing in these times. Not certain I would ever be able to document that, given the workload that lies ahead over the coming year-plus. But thank you for bringing it to my attention. I will ponder…" I'm grateful he responded at all. As Pastor Chris sang, "Just a Few More Miles (I've Got No Reason to Quit)."

Check out more like this:

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmSteven Garnett

The TonearmSteven Garnett

Comments