I've never been to Chicago. I think I know what it would be like, given the inordinate media coverage the city attracts, both good and bad. When I think of this city, my first thoughts are of house music, the Art Ensemble of Chicago/Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), and Chicago blues. At a push, I might think of the musical Chicago or even the seventies soft rock band Chicago at one extreme or, at the other, record labels Thrill Jockey (I do own a Thrill Jockey woollen hat in claret and blue) or International Anthem Recording Company, both labels being based in Chicago.

International Anthem released a mixed CD by Gilles Peterson last summer. He was one of the first UK broadcasters to champion early drum and bass records (like Roni Size's debut) and the music that later evolved into the sound that became known as IDM, with the likes of Aphex Twin and Squarepusher.

So, to join the dots between nineties UK dance culture and Chicago's Lynyn (aka the electronic music project of composer and multi-instrumentalist Conor Mackey), how does a new album sound so fresh with UK references in 2025? Mackey has stated an early influence from the non-Chicago likes of Roni Size (from Bristol, a historic port that has seen international trade over hundreds of years), Aphex Twin (raised in Cornwall, a county in the South West of England mostly known for agriculture and tourism), and Squarepusher (Essex, hotbed of Essex girls and wide boys).

And then make the seismic jump to his Lynyn's debut album, Lexicon, from 2022. DJ Mag has called Conor "One of IDM's next visionaries,” and there's definitely been a bit of an upsurge in tracks infused with DnB/IDM of late, such as WheelUp (Tru-Thoughts), Alexander Flood (Atjazz Record Co.), Berkeley Hunt (Soul Quest Records), to name just three. We even had a Raz & Alfa cover of Aphex Twin's "Windowlicker" this year!

As for Lynyn, beyond these influences, he thinks of sound as a pure object unmoored from physical gesture, existing only as itself. Mackey, who writes functional music informed by neuroscience for BrainFM and plays guitar in the avant-jazz group Monobody, spent years absorbing the propulsive intricacies of the aforementioned UK electronic music stalwarts. More recently, he has pulled the thread toward turn-of-the-millennium minimal dub techno—Pole, Basic Channel, and Jan Jelinek's Loop-Finding-Jazz-Records—integrating vinyl crackle, micro-percussion, and hovering pad layers into his established vocabulary. The result drills down into how clusters of artificial shards lock together, how machine-made fragments cohere into something that breathes and moves.

This is where we come to Lynyn’s follow-up, Ixona, which takes things a little bit further. Released on Sooper Records (another great Chicago label), Mackey may, in turn, be referencing sharply focused Four Tet inclinations, a bit of Floating Points, and a classically trained philosophy into his first love of drum and bass/IDM.

So definitely time we thought to get in on the loop and find out more.

Gerry Hectic: Your music gets tagged as 'forward-thinking IDM', but Ixona pulls from minimal dub techno, drum and bass, acid house—a wide sonic palette. Was there ever a moment when you considered focusing on just one of these directions?

Conor Mackey: My work has always felt, to me, like an attempt to synthesize stylistic elements from all the music that has influenced and shaped me as a musician and composer. Sure, I've definitely thought that maybe focusing on one style would be the 'right' move, but whenever I write highly stylized music, it has never felt very personal, never really felt like my voice. I'd say that the mix of styles is essential, part of the 'working out' and process of discovery of my own expression.

Gerry: How do these directions translate to live performance? Do your sets progress, journey-like, through many different musical styles?

Conor: Yes, that's absolutely how I approach creating live sets. I was classically trained, and the bassoon was my primary instrument during most of my music education. I played in the symphony orchestra throughout middle school, high school, and college, and studied music theory and composition. I love classical and concert music, and it's had a profound impact on the way I think about form. I see a live set as an opportunity to create a large-scale piece that takes the audience through a variety of movements, each linked by interstitial moments. It's a unique chance to play with form and also to reimagine tracks from the album, totally recontextualizing the instrumentation and presentation of that material.

Gerry: You’ve mentioned struggling to figure out what minimalism means for you personally, and that Ixona might be your first step toward more minimal expression. How do you reconcile maximalist tendencies with this pull toward reduction?

Conor: Minimalism and reduction feel like maturity to me. The ability to whittle down excess to get at something eternally true. As I've gotten older, I'm not as enraptured by virtuosity and density as I once was and have found myself enjoying simpler, more direct music. I particularly admire artists who have this sort of direct and focused expression. I'm not sure how I reconcile those maximalist tendencies, but that is the exciting part. The process of giving voice to that pull towards reduction might result in something interesting, something new for me. Hopefully, fanciful ornamentations get sacrificed, and what is left is vital.

Gerry: The press materials describe the album as tracing "the contours of a vivid but unreal place" that can only be reached through the music. This sounds almost like worldbuilding. Do you consciously construct these imaginary spaces, or do they simply appear?

Conor: I think that is just the nature of music. I love Goethe's concept that architecture is frozen music. There's something deeply true in that comparison. Walking through a building, moving through different rooms, noticing how each space has its own character and mood, feels so similar to if you were able to capture the physical essence of music. But, in music, the architecture itself flows around you. The structure changes as time passes. Music is architecture in motion, space that gets reshaped moment by moment while you stand still within it.

Gerry: Track titles like "4m Hiero," "RESton," and "Versilitude" feel like they could be coordinates or technical terms. Are the titles meant to complement the "imaginary other space" concept?

Conor: Absolutely. The fantastic and oftentimes invented titles are part of the sort of 'otherness' that I feel like instrumental electronic music evokes. Most of the time, track titles come up spur of the moment when I'm working on them. Sometimes they are named after a primary synth patch that I hastily created, like "4m Hiero." Other times, they may be corrupted versions of file names.

Gerry: The album's emotional range is striking—from the gentle arpeggios of "RESton" to the trombone-laden "Pad C U." How did the collaboration with Brendan Whalen come about?

Conor: I think we met sort of randomly at a release show party for the Chicago band Ratboys. Had a great chat about music and exchanged numbers. We got together at my friend and fellow Monobody member Steve Marek's studio to record. No plan in mind, just getting together to see what would happen. Brendan is an amazing player, beatmaker, and improviser, and we recorded a bunch of material, and then I quickly edited it down into some different ideas and added some Eurorack percussion, and the tune evolved from there back at my home studio.

Gerry: What draws you to add organic instruments to your electronic productions?

Conor: Organic instruments bring a sense of realism and physicality into an otherwise totally synthetic piece. I don't necessarily think about it like that when I'm writing; usually, it's more that I hear a particular instrument or timbre implied in what I'm working on, and I follow that intuition.

Gerry: Your four-year collaboration with visual artist Owen Blodgett suggests this isn't just aesthetic accompaniment but integral to the Lynyn project.

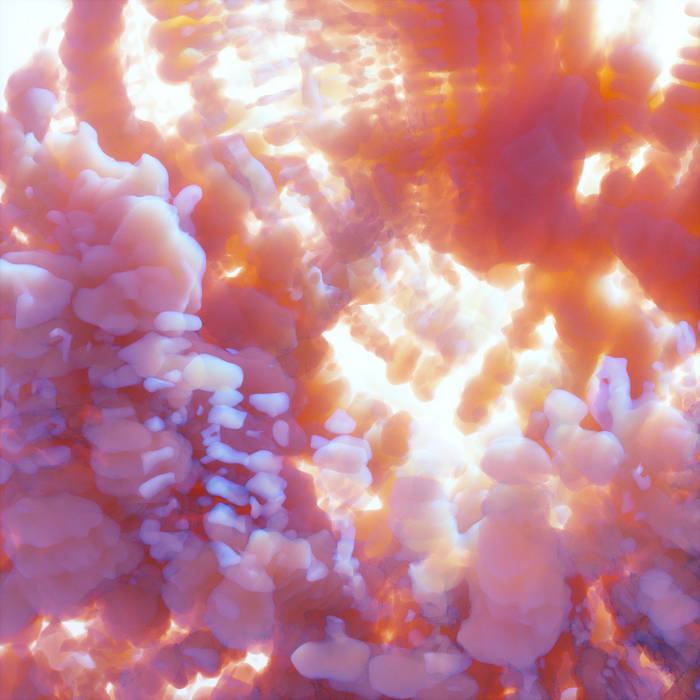

Conor: Yeah, Owen and I almost always perform together, and I think that I've only performed once without his visuals being a component of the live show. Really, we just hit it off when we first met and were fans of each other's work. I think our different approaches are indicative of the timescale of energy that each is trying to capture. With the live visuals, the energy is immediate, and the nature of my music is rhythmically vital. Owen is capturing that in the moment through his visual engine. It's audioreactive, so it takes direct input from different parts of the music and reflects that visually. The album artwork is more about capturing the essence and feeling of the album as a whole, in a static way, outside of the passage of time and sequence of events.

Gerry: Chicago's electronic legacy runs deep beyond house music. Are there any local producers—past or present—whose work resonates with you?

Conor: Certainly, especially in relation to the first question, a major influence on me is the Chicago band Tortoise—a perfect example of a group that was really successful in taking a myriad of stylistic influences and melding them into a unified voice. Their albums don't feel like they are hopping around from one genre to the next; rather, they refract the idiomatic characteristics of a variety of styles into a presentation that feels singular. This has always been a goal in my own work.

Gerry: That's interesting, as the Tortoise track I know best is Derrick Carter’s remix of "In Sarah Mencken, Christ And Beethoven There Were Women And Men.” It’s a prime example of how leftfield can have an injection of club energy, like your track "4m Heiro" which is more dancefloor than some of the album's introspective moments. Do you think about dancefloor functionality when you're recording, or does that just happen?

Conor: I'm not thinking about my tracks in any sort of functional way, really. I think this is simply a byproduct of the fact that much of the electronic music I love is beat-driven and informed by, or influenced by, dance music. The physicality of groove and the integrity of rhythm certainly are of major importance to me, but I never think to make sure my tracks hit on the dancefloor when writing.

Gerry: Your 'day job' involves writing functional music informed by neuroscience principles. Does your scientific understanding of music's effects on the brain influence your artistic work?

Conor: No, it doesn't. It is two totally different modes of writing. One is functional and highly stylized, the other is personal expression and the search for a unique voice manifested. I'm not thinking about neurological responses exactly, but composing music with consideration of how brains react is basically the whole point!

Check out more like this:

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

The TonearmSara Jayne Crow

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

Comments