Swedish composer Amina Hocine transforms hardware store materials into an instrument that defies expectation. Her creation, which she built from PVC pipes, ball valves, and an air compressor, produces sounds that seem impossibly electronic, spreading what she calls 'sound crystals' through space. These frequencies shift and refract depending on the listener’s position to the instrument, creating an acoustic phenomenon more akin to light than conventional music.

The project began at Ställbergs gruva, an abandoned iron mine turned art center, where passing trains sparked an obsession with foghorns and signal sounds. An attempt to control these industrial tones became something far stranger: an organ that breathes, complains, and demands careful attention. Each pipe develops a personality—one pulsates anxiously when starved of air, another grumbles weakly, while a third maintains unwavering stability.

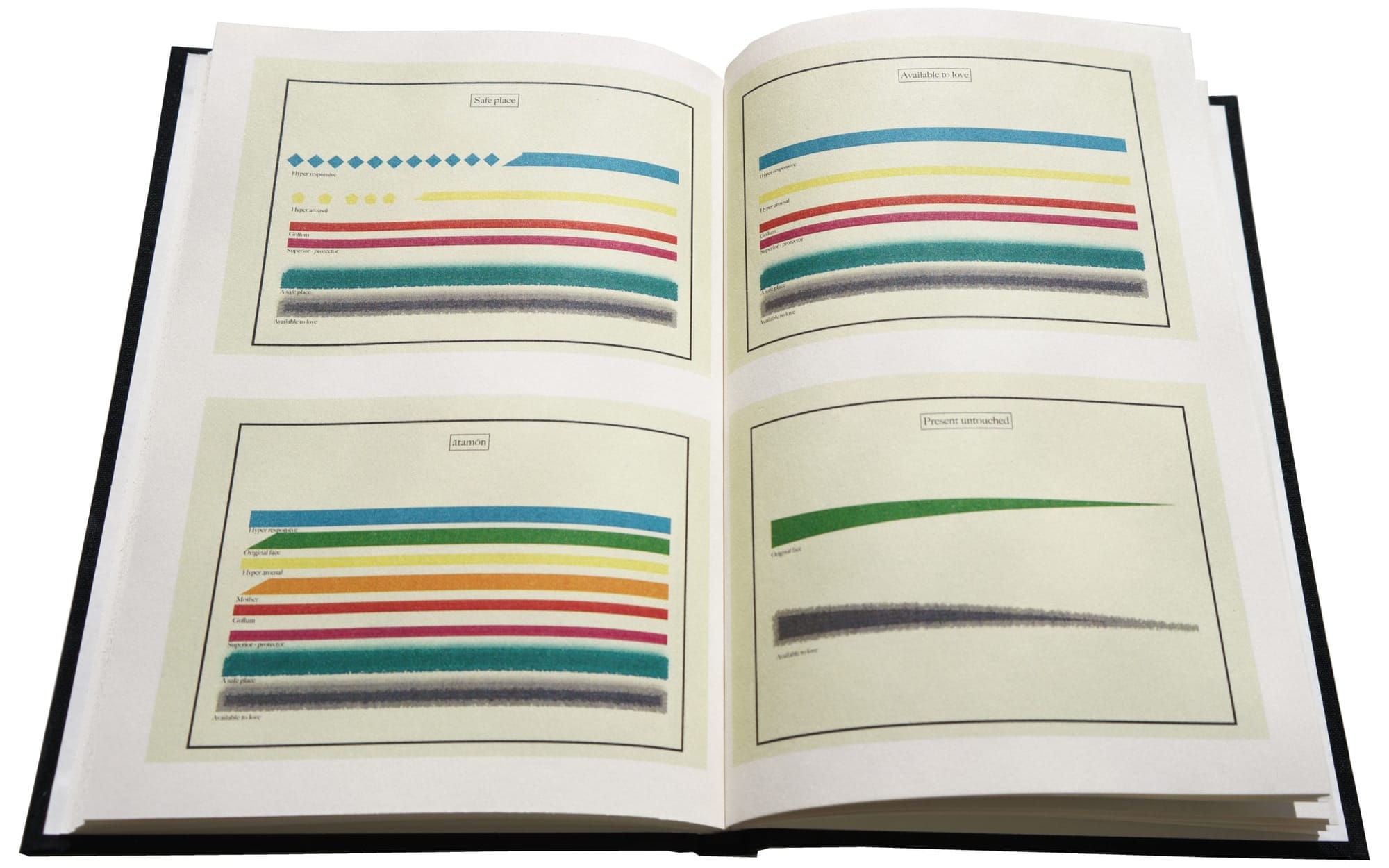

For her album ātamōn, each pipe embodies a psychological archetype drawn from years of spiritual and therapeutic work. The title, pulled from Old High German meaning 'to breathe,' captures how the instrument functions less like a machine and more like a living organism that teaches presence through immediate sonic feedback. When played in the mine's reverberant spaces, the instrument enters into dialogue with its surroundings, creating what Hocine describes as "wordless theatre, where frequencies act out tensions, longings, and contradictions."

Lawrence Peryer: What sparked your fascination with foghorns and signal horns that led to this project? Was there a specific moment or experience that made you think, "I need to understand how to make this"?

Amina: It was while attending a residency at Ställbergs gruva in 2021. It's an old iron mine turned art center (where I ended up recording the album in 2023), and it's situated between two train tracks in a valley. I was captivated by the sound of the train horns, and the idea grew as I was discussing it with my friend and residency collaborative partner Rasmus Persson. I needed to see if it was possible to make an instrument with which I could play this sound that you're usually just exposed to. I have always been fascinated by alarm sounds, foghorns, and sirens. There is a confident melancholy ingrained in the sound.

Lawrence: How did you discover that PVC pipes and HVAC components could produce such haunting, electronic-sounding tones? What surprised you most about these materials?

Amina: The instrument creates a sound that makes what I call ‘sound crystals.' If you just slightly turn or tilt your head, the sound shifts, like turning a prism in sunlight. All of this work has really been like following a thread and seeing where it takes me. A vital part of this instrument is the membrane holder (holding a rubber material working as an oscillator), designed by someone (Benjamin Wand—"better call it art" is the channel name) I found on YouTube, searching 'Foghorn diy.’ It's an open-source 3D-printable membrane holder, designed to be put on a PVC pipe. So following those aisles in the hardware store, the design kind of revealed itself, and also in conversation with Rasmus, who had just renovated the plumbing in his summer house. I said, "I want levers to control the airflow!" And he said, "I know just the thing: Ball valves!"

The biggest surprise was how electronic it sounded and the sound crystals that emerged. I have never experienced that phenomenon as profoundly before. The construction and instrument were a great success from the start. I haven't made many changes to the original idea (though I have made five different versions, each representing its own composition). But I also decided early on that a key part of the instrument's philosophy is 'sound wave surfing,' both in terms of how I play it, following what it wants me to do, but also in terms of not overcontrolling what it is. The weak parts of the instrument have become its strength.

Lawrence: How do conversations with your spiritual advisor translate into actual compositional decisions?

Amina: I need some kind of structure in order to compose, like a skeleton. The spiritual science has been acting as a guidance in finding different skeletons. With ātamōn, it was about not counting out any parts of a human as unnecessary or bad, but simply just a part of the whole. I took the parts that my therapist (another person than the spiritual advisor, but still informed with the spiritual science of Martinus Thomsen) and I had been carving out over a year, and gave each pipe its own role to play. Like Gollum, the shadow creature living in all of us.

Lawrence: You've performed in everything from galleries to abandoned mines. How does a space change your instrument's voice?

Amina: The space is everything, really. My instrument doesn't behave the same way in any two places. At Ställbergs gruva, the reverb is pretty long, and it's almost like the mine itself starts playing with you. In a drier room, I compare the sound to lasers, which is an experience in its own. But in the mine, the sounds return to you altered, ghosted. It taught me to surrender more, to listen with my whole body. That space didn't just reflect the sound—it absorbed and responded to it.

Lawrence: You studied electroacoustic composition formally at the Royal College of Music, but your instrument feels deeply intuitive and personal. How do academic rigor and spiritual exploration interact in your work?

Amina: The academic training gave me a language and tools, but I always knew I needed to move beyond them. My spiritual practice reminds me to stay receptive, to let the unknown have space. It's a bit like composing with one foot in structure and the other in free fall. I often start with intuition or a felt sense, and then use the academic tools to shape, not control. The trick is not letting the intellect drown out the deeper listening.

Lawrence: In ātamōn, each pipe represents a psychological archetype like "The Safe Place" or "Hyperarousal." How do you assign sounds to psychological states? What does a state like hyperarousal sound like through a PVC pipe?

Amina: I started by deciding which tones I wanted and cut the pipes. It was then, when listening to them, that I realized they all had their own personality. Extremely different. Even though the material is the same for all of them, all that differs is height and/or width. When I tried the pipes "Hyperarousal" and "Hyperresponsive," they are quite literally that. When they don't get enough air, they start to pulsate like an alarm! And when I give them more air (more attention), they calm down and the tone stabilizes. "Gollum" has a weak, grumpy, and kind of complaining sound, very sensitive to the airflow as well. "Original face" has a very stable and clear sound. So the process is just listening and assigning roles.

Lawrence: You chose "ātamōn"—Old High German for 'to breathe'—as your title. Why reach back to that particular linguistic root rather than using contemporary language about breath or breathing?

Amina: If I were to use the Swedish term 'att andas,' for me, the connotations are so broad and ordinary that it is hard to really connect to what it is trying to say. It would be the same in English. Things need contrast in order to stand out, and if you are not aware of what a word means, when learning the meaning, you have an opportunity to take it in much deeper.

I thought of how the word 'to breathe' and 'spirit' are often connected, and I thought of 'Ātman,' the Sanskrit term for true and eternal self. When looking around for what spirit and breathing were called in different languages, I stumbled across ātamōn, and it immediately stood out as its own entity. It reminded me of Ātman, but put the word in Europe. A place closer to home for me.

Lawrence: The ātamōn version places eight pipes around the audience rather than keeping them together. How does this change the listening experience? What happens when the instrument surrounds people instead of facing them?

Amina: Well, firstly, it heightens the sound crystals and spatiality and depth of the sound. And the pipes' individuality becomes clear. When they are all together, they serve more as a collective, and it can be hard to differentiate different tones. But when they are spread out, both as a visual and also a sonic cue, each character really stands out as its own entity.

Lawrence: How do you capture the acoustic memory of industrial space? What does that history add to the sound that a purpose-built studio couldn't?

Amina: It's always a privilege to work in a space that wasn't originally meant for art, especially not experimental organ music. I'm drawn to those kinds of places where you feel like you're behind the scenes of something, and this project really thrives on contrast. When you place something odd, like this organ, in a room built for heavy machinery, something shifts. The sound is shaped not just by the acoustics but by the memory of the space. And for the people who've lived near the mine for generations, the sound might trigger memories of work, of machines, of a very different kind of daily life. That recognition opens up new ways of listening. Someone who wouldn't normally attend a concert in a formal hall might feel connected to the piece. The instrument becomes a kind of Trojan horse, with its parts being recognizable, in a familiar place for them, but it carries something deeper and unexpected inside.

Lawrence: When you're playing these archetypes against each other sonically, what are you learning about yourself?

Amina: The whole process of working with this instrument has deeply transformed me. It continually reminds me to let go of control and to breathe, be present, to not perform or judge. Just listen, accept, and respond. In that sense, it's become a perfect mirror for self-inquiry. The instrument resists being controlled; it wants to be listened to. And when it's truly heard, it responds with something magical.

If I'm not present and if I rush or pull a valve too harshly, a pipe can literally scream. It reacts immediately to any forcefulness or inattentiveness. That kind of direct feedback is rare, and it demands a certain quality of presence that I carry with me into other areas of life.

I often find myself referring to my work with the instrument in everyday conversations, about relationships, emotions, or decision-making, because it has genuinely taught me something fundamental. My spiritual teacher often says, "Enlightenment is easy—just drop your opinions." That phrase echoes in this work. You might look at PVC pipes and see something crude or even ugly. But when you really pay attention, when you care for them and give them context, they can become something visually striking, even poetic. I think that's part of what this whole process has been about—redefining value through presence and attention.

Lawrence: You call ātamōn "wordless theatre, where frequencies act out tensions, longings, and contradictions." What's the difference between ātamōn I and II in theatrical terms?

Amina: I have never played ātamōn II live, since the way we recorded it was by walking around the droning instrument super slowly, with handheld recorders. I would, however, really like to try out inviting the audience after a concert to play ātamōn II themselves by walking around the instrument and listening to the shifting sound crystals.

In ātamōn I, what is present is that the instrument is very unpredictable, and I feel almost like a teacher, keeping all the students on track. I really feel like each pipe is a person that I'm listening to and reacting to, to finally balance all of them together.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments