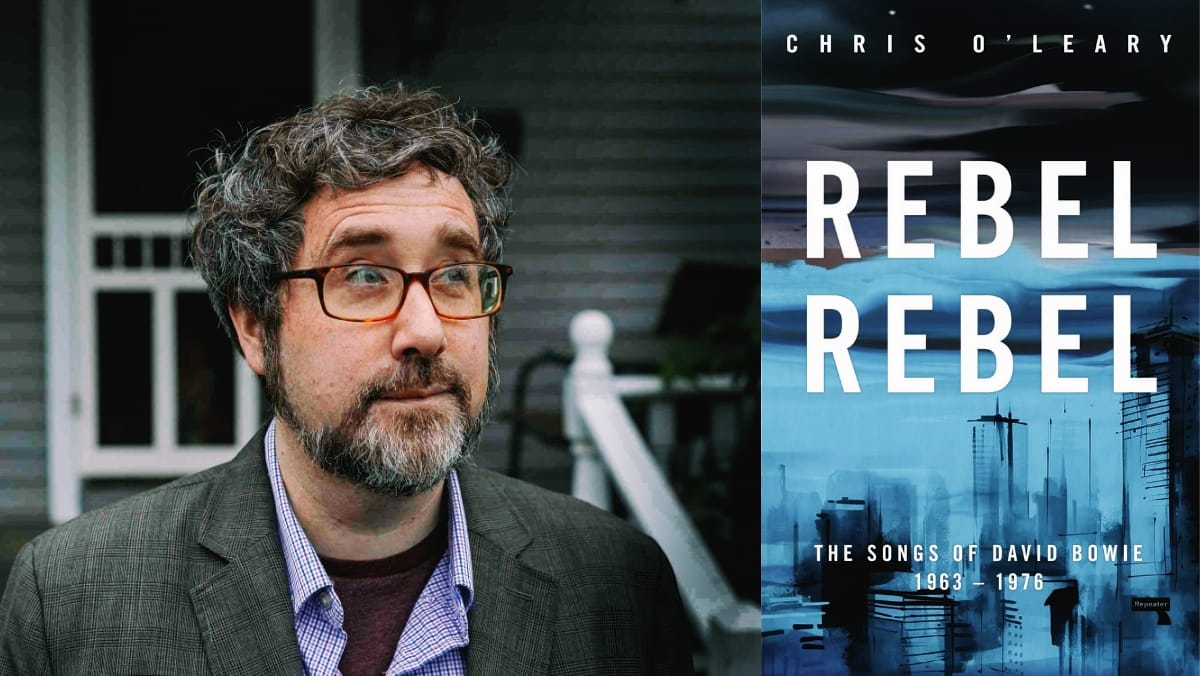

David Bowie recorded roughly 450 songs over half a century. They span cabaret, psychedelia, folk rock, glam, Philadelphia soul, avant-garde instrumentals, and stadium anthems. Chris O'Leary's Rebel Rebel: The Songs of David Bowie, 1963-1976 and its sequel, Ashes to Ashes, examine them chronologically, tracking how Bowie's songwriting shifted from one session to the next. Since their initial publication, these volumes have become standard references for Bowie enthusiasts and music historians.

The new edition, published July 8, 2025, represents a full revision enhanced by a decade's worth of released material. Box sets issued after Bowie's death brought demos and alternate takes into circulation, and bandmates and collaborators published memoirs with firsthand accounts of recording sessions. This expanded archive reveals the stories behind the songs, the pioneering studio techniques, and the cultural context surrounding Bowie’s early work, including his literary influences, cinematic inspirations, and relation to musical contemporaries such as Marc Bolan, Bob Dylan, and Lou Reed.

O'Leary has added entries for over two dozen previously unexamined tracks and revisited every existing chapter with new information about Bowie's recording process, influences, and live performances. The book explores how choices in arrangement, mixing, and production come together to create the final recordings. For enthusiasts fascinated by the birth of Ziggy Stardust and anyone interested in how an artist builds a musical language, Rebel Rebel offers an essential companion to Bowie's formative years.

O'Leary holds an unusual position in the music writing world. He works neither as an academic nor as a conventional critic, but rather as a close listener with a forensic ear. His work examines lyrics alongside bass lines, as well as production choices alongside cultural context. He attends to the mechanics of recorded songs: where instruments sit in the mix, how arrangements build tension, and which takes Bowie chose and why those choices matter. O'Leary writes with technical know-how while remaining accessible. He makes arguments about musical structure that don't require an understanding of music theory.

Chris O’Leary was a recent guest on the Spotlight On podcast. His conversation with host Lawrence Peryer touched upon O'Leary's method and relationship to Bowie's catalog across multiple revisions. He also expresses his concerns about whether the kind of work he does will remain possible and whether the rich corpus of criticism that supported his research will exist for future writers.

You can listen to the full conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, clarity, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: On this occasion of the new updated edition of Rebel Rebel, something I've been wanting to ask you about is this: of all the revelations and all the updating that you had to add from the last decade, were there any items that came across to you as particularly interesting or surprising?

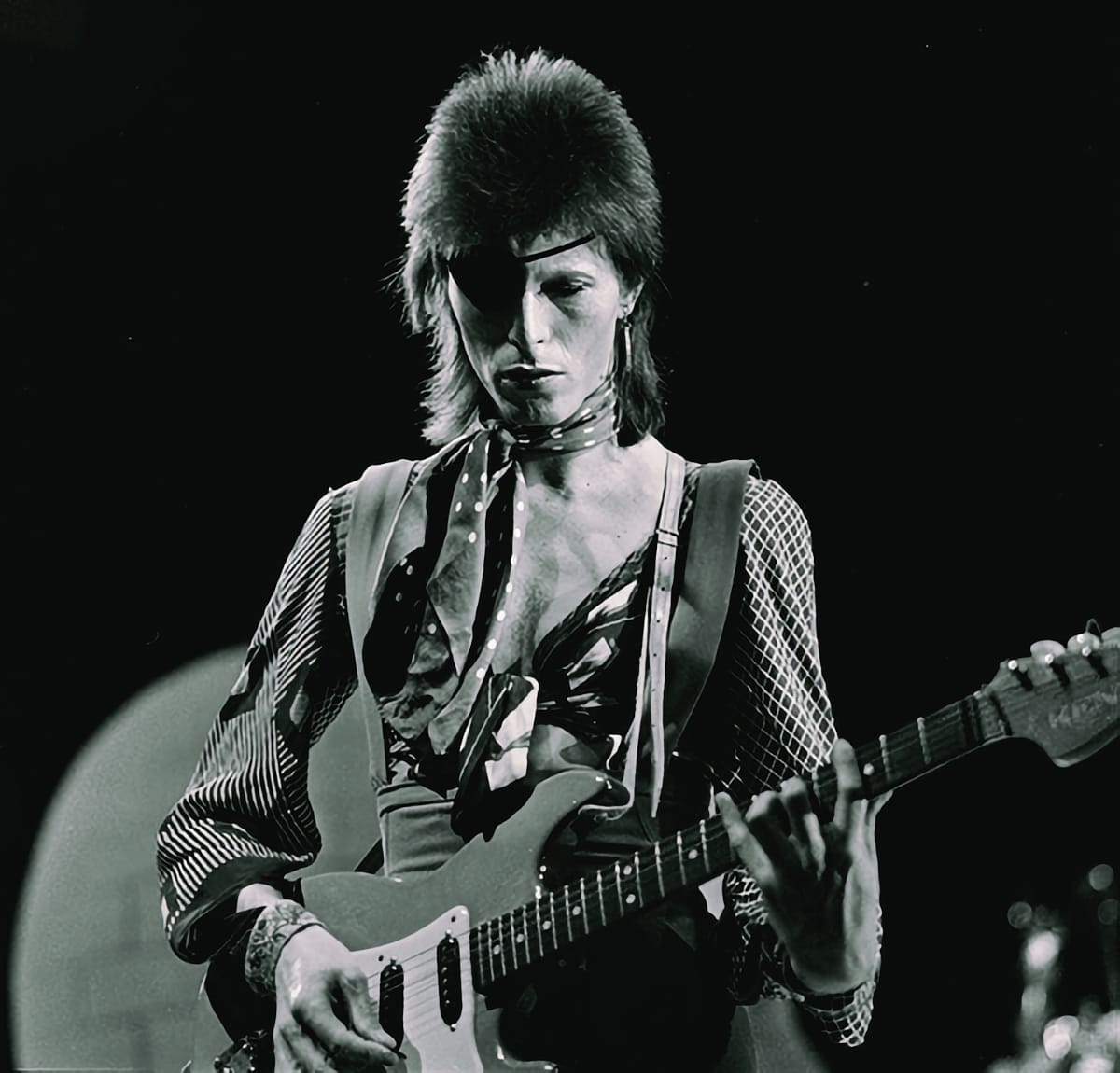

Chris O'Leary: There were a few things. One is my misperception about how much storyline Bowie had done for Ziggy Stardust. I thought that he had kind of made up the story about Ziggy after he made the album. When he was talking to William S. Burroughs in late 1973, discussing ‘black hole jumpers’ and Ziggy as an extraterrestrial messiah figure, it all felt like the stuff he had come up with after he had written most of the songs.

Now, with the release of the demos, particularly the notebooks in the box sets, Rock and Roll Star and Divine Symmetry, you really can see that he spent a lot of time thinking up the book of the play that was never made, the narrative. He really did have this kind of structure in mind, and it changed the album for me. I can see how “Velvet Goldmine,” for example, fits in much better with the storyline now, as there was supposed to be a character called Zip who was Ziggy Stardust's manager. The manager would be singing "Velvet Goldmine" to him. Obviously, you can have your own interpretation of the song any way you want, but it's interesting to be like, "Oh, okay, this was intended as a stage role for this part that was then cut." Maybe that's one reason why he cut the song from the album. I think many fans would argue it probably deserved to be on there more than something like "It Ain't Easy," the Ron Davies cover that was actually recorded during Hunky Dory.

Lawrence: Something that maybe doesn't get mentioned enough in the context of your work, and I'm going to right that wrong, Chris, is—first of all, I really struggle to think about Pushing Ahead of the Dame as a blog. It seems such a small word for such an ambitious and rigorous undertaking, but I don't need to get hung up on the semantics on your behalf if you're okay with it.

Chris: Yeah, it's fine with me.

Lawrence: I actually have come to really think of what you do as, in a way, a predecessor to what Andrew Hickey's doing with the A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs podcast. How did you choose to elevate the blog as a medium? I guess that would be the way I'd say it, because you could have done much less.

Chris: The important thing is that I did not set out to do anything of the scope that it became. I think if that had been the plan from the beginning, it probably would have failed. I think it only survived and grew because my expectations of it were so low. I had started doing—now this will date me—it was called MP3 blogging in 2004. I had thought about writing about music for some time, but I wasn't really connecting with what was popular at the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, so I didn’t have much to say about a lot of the music that was out. It also seemed so daunting to try to break into whatever was out there then.

Suddenly, there was this kind of vogue for do-it-yourself publishing, based on the Blogger platform for the most part, and that's how it started. It was a blog called Locust St., and the idea was to do a song for every year of the twentieth century. Then I realized I didn't really know much about the 1900s or the 1910s, so I thought, "I'm going to start after the war, 1945, which I know a little more about." Then it kind of went on from there, and then I went back to the start of this century. It was not like a huge success by any means, but it had a small readership, and I liked doing it. It was a nice distraction, but I was starting to feel burned out.

So I thought, well, maybe to rejuvenate myself, I’d try another blog thing, with the idea that it’d be a side project and I might abandon it at some point, but it would be nice not to have to think about recreating 1947 or something similar. I had gone through a period where my personal life was in upheaval, and so one of the things I did to ground myself was have lunch with my dog. I had the book Revolution in the Head by Ian MacDonald, which is a song-by-song, chronologically ordered account of the Beatles. So, every day, I would get the MacDonald book and listen to the song while I had a sandwich, and then I would read the entry. I thought, this is a kind of fun way to listen to the Beatles, because I had heard the Beatles ever since I was a child, but I mostly knew them through album sequencing or what have you. But to go through the songs in the order they were made and think about each one over the course of fifteen minutes—I thought it was really a perspective I hadn't had before. I thought, "Boy, that would be fun to do this in a blog format."

When the blog first started, I was going at a really fast clip. There were like three entries a week, which seems absolutely superhuman to me right now. As the year went on, the tension was taken away from the other project I was doing, and the Bowie thing took up more time because I got ambitious with it. But I never had the idea that it was going to be a book or anything. Then it was picked up by Tom Ewing, who runs a blog called Popular, and then it was weirdly picked up by Time magazine, of all things. Time magazine wrote about it, and The Guardian and a few others. More and more people would come, and a good comment section developed. Through that, Tariq Goddard, who was then at a publisher called Zero Books, contacted me and said, "Do you want to turn this into a book?" That's how it started.

It was always a bit haphazard and not really planned out. I consider the books, particularly this revised version of Rebel Rebel, to be my final word on the subject, even though I'm sure I'll disagree with myself at some point in the future. But now there are three different versions of what I thought—three different moments in time as to what I thought of a song like "Cygnet Committee.” If you really wanted to, you could compare the 2009 blog entry to the 2015 book entry to the 2025 book entry, and you might see I have grown up in some ways, or grown down.

Lawrence: Now I know what I'm doing this afternoon. Thanks, Chris. (laughter)

Chris: I do think it came about in this, to use a word for lack of a better one, in an organic way. I did not have a master plan summer of 2009 that this was going to be a two-book series. It was much more slipshod than that.

Lawrence: I think a lot of us have seen projects, whether they're our own or other people's, that start with a flourish and a statement, like, this blog is going to be this. Then after a few weeks, it's in the graveyard of abandoned projects.

Chris: It's hard to keep it up. It's frustrating. I totally get it.

Lawrence: Would you have ever let yourself stop, or did you ever have a conversation with yourself where you were like, "Come hell or high water, I have to do this now?"

Chris: I'm trying to think if there was a moment I hit a wall. I don't think so. There was a time when I was working on revisions for the first version of Rebel Rebel, and at the same time, I was doing new entries, which I believe were for Earthling. So it was this really hard transition between revising the sixties stuff and then having to write new stuff on mid-nineties material. I think I may have put the blog on mini-hiatus then because it was just too much. It was exhausting.

The other time was after Bowie died. There were probably five or six songs left, and I just didn’t have the heart to do it anymore. I just felt like everything had changed, and it felt like a big curtain had suddenly dropped, and the blog had to become something different. It couldn't be what it was. But by the time I was really getting rolling, I felt like I was too much of a completist, and I couldn't be the guy who abandoned the Bowie song-by-song guide before he even hit "Ashes to Ashes." I didn't want that on my gravestone, you know - “He had a good idea, but it didn't work out." So I kept with it, by gum. (laughter)

Lawrence: It's easy to forget how wrapped up everybody was in the power of Blackstar. Then all of a sudden we have it for three days, and this other event completely recasts what the album apparently could have meant, the whole mythology of it being the audio death mask, you know, a really incredible moment. It was one of the few celebrity passings where it felt like the intensity of the emotion took months to die down.

Chris: Yeah, and it was just a strange, dispiriting year because you feel like when everybody had started coming to terms with Bowie, then Prince died. I believe Prince died in April. It felt like a series of shocks kept happening throughout the year. Leonard Cohen’s death at the end of it, and George Michael’s, it was almost like somebody was writing it - a tragedy that year, 2016. I mean, it was just like the wheels really fell off.

Lawrence: And then we had a certain presidential election.

Chris: Yeah, and Brexit happened that summer. It was just everything kind of happened. It feels like a real hinge year.

Lawrence: Could you tell me a little bit about how you listen? I kind of mean it from a process point of view. I have this image of you in a listening room with a chair and a pad and a quill, thoughtfully stroking your chin as you're listening to each track. (laughter)

Chris: When I was doing it, I would know the next album or the next period, listen to it in the background while I was cooking or something to kind of get into it. Then, when it was time to really dig into the song, I think I just put on headphones and listened to it a couple of times. If there were sheet music, I would use that as a basis and then write over it the drum lines, bass lines, and so on. I had this big pile of research by that point. And then kind of searching through, what did Bowie say about this song in various interviews? What were reviewers at the time saying about it? So getting all of that in and then just listening to it four or five times in a row to train myself to be like, "This time I'm going to listen to the bass," or "This time I'm going to listen to what the backing singers are doing."

The thing I really wanted to do from an early point was to make it as much a study of the music as it was of the lyrics. I think, understandably, when people write about music, it's often about the lyrics. What is the person singing? What do the lines mean? What's the imagery? That's very important, and I don’t downplay that. But this is recorded music, and these are people in a studio playing. It's being mixed in a certain way, and choices are being made to arrange things in a certain way, and all that comes together to make the final song.

So, it would be like a day or two of this kind of tedious, back again, first minute, second minute again, just what am I hearing? Then the writing. This was faster back when I was younger. I could do it in a couple of days, and at some point it became, "Oh, this took a week or two weeks." It was never an extremely long time.

Unfortunately, I didn't have a cork-lined or soundproof room with quadraphonic speakers or anything. It mainly was a Discman and headphones, at one point, and then the iPod and my living room speakers. That's pretty much it.

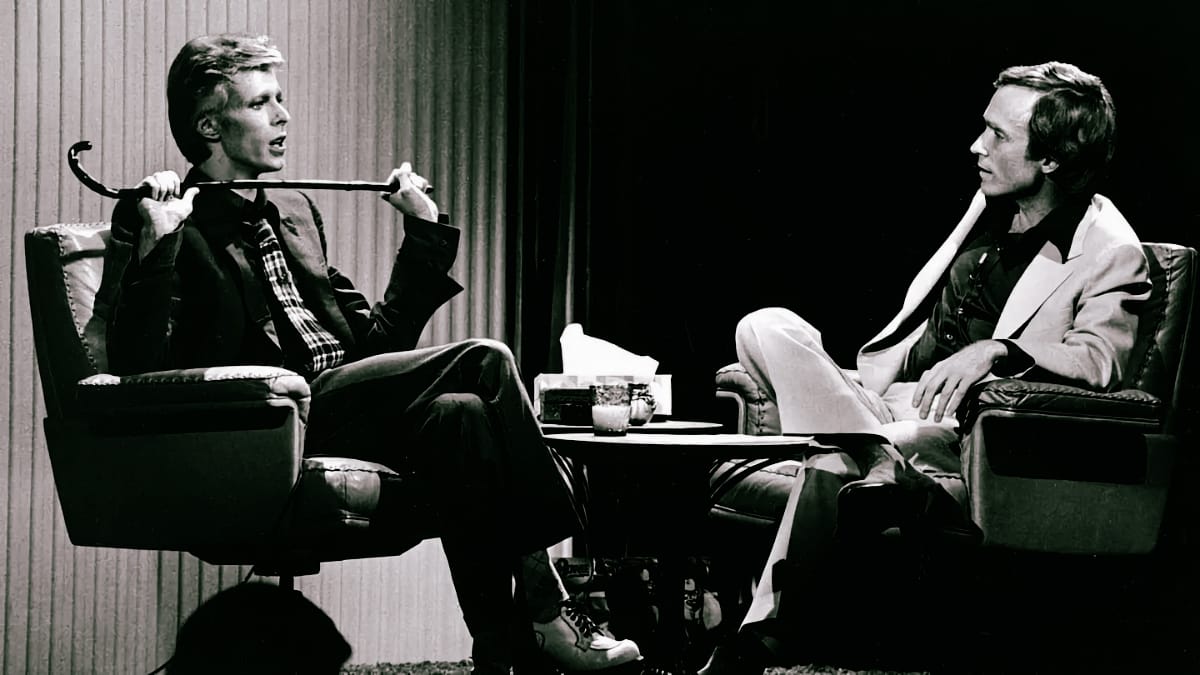

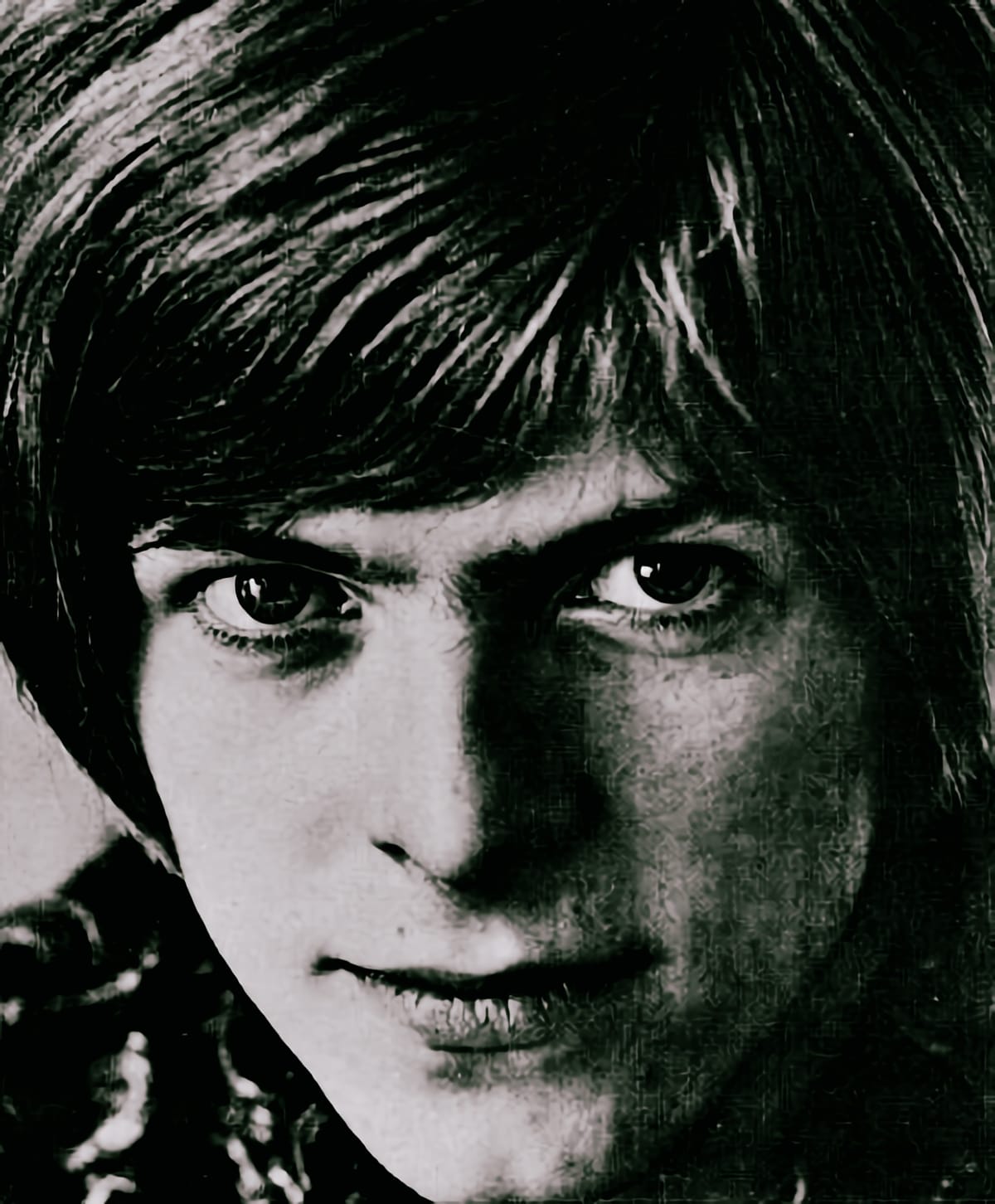

David Bowie publicity photo from 1967 and on Top of the Pops in 1974, both images via Wikimedia Commons.

Lawrence: You work at this nexus of academic study and fan devotion, being rigorous yet having an accessible voice, which seems to be a significant part of your success and your ability for your work to connect with your audience. What lineage do you see yourself in?

Chris: Obviously, there are music writers who I loved when I was first reading rock criticism—Greil Marcus, Jon Savage, Charles Shaar Murray, and people like that. There are writers whose work I will always read when I see something by them, like Nate Patrin, Michelangelo Matos, and Amanda Petrusich. I don't really consider myself a rock critic, or anything like that. What I do is kind of odd, and I was never part of that world. Nor do I remotely think I'm like an academic. I got a bachelor's degree in journalism. That's as far as it went. So, I don't know what I do, really. I don't think I'm aligned with anybody. I do feel a sort of simpatico soul with Andrew Hickey and his podcast. I understand where he's going.

What I did, I don't know if it could be done today. I fear there's a societal push to downplay writing at this point, to make a more visual society, with AI replacing what people, human beings, once wrote. For example, when you go back, writing about Bowie in the seventies, you can expect that if he went on tour or put an album out, that there's going to be dozens of pretty well-written reviews of his concerts and reviews of his records and in-depth interviews with him, whether it's radio people or magazine writers or newspaper writers or fan writers. There's this great corpus of material to use.

Now I wonder—I guess Taylor Swift is not a good example because I still feel like there's just tons of writing about Taylor Swift, but I'm thinking of maybe a second-tier person. I don't know if that infrastructure is there anymore. If it’s the year 2050 and you want to write about, I don't know, Bruno Mars or something, what’s going to be there? Is the stuff going to survive? Or the YouTubes and TikToks and podcasts—is the technology going to be there in thirty years for that stuff even to get played? Will anything be archiving it? Will AI mash it all up, and it becomes this kind of Wikipedia voice, this crap that's all over the internet? I just hope that there's a pushback against that because I think it is a loss. The stuff that I was able to do with somebody like David Bowie, I don't know if somebody's going to be able to do simply because the research, the reference material, is just not going to be as dense. It won’t be as rich.

Lawrence: And it's such an era of publicist control as well that you won't get some of the philosophizing that David would do.

Chris: Yeah. You think of all the interviews, all the great interviews with him, where he's just going off. Pete Townshend is another great example, and Neil Young. They would sometimes say absolutely crazy things, with no filter. It just feels like there's nobody who's famous right now who's doing anything like that because they're scared witless, probably, and rightfully so, because if they said one thing that somebody could take out of context in any way, they're going to get lambasted for it, or the president will call them out in a tweet or something insane. So I understand the wariness and the corporate boilerplate speak that everything seems to be written in right now.

Lawrence: I definitely hear you and relate to what you're saying. But I try to be careful not to let that bleed into me becoming a cranky old man.

Chris: Oh yeah, very much. I do think there’s a great future in podcasting, and I hope that if video is the future, there will be people who are really adept in video who can make video a more archival and rich medium. I just fear in the latter case. You can’t play a CD-ROM from even the late nineties. I do wonder if that stuff will be technically accessible.

Lawrence: Even David Bowie’s website—so much of that stuff's gone, like the little Flash things that were built.

Chris: There's so much from the 2000s. Someone had a good point that it's probably easier to find a primary source from the 1930s than it is from the 2000s right now. At least all the newspapers are on microfilm somewhere. All the alt-weeklies, all the zines. That stuff is incredibly valuable, and I do hope some version of it continues. I feel like it's more of a challenge now.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments