A clarinetist and an electronic musician walk into a bar—that sounds like the set-up for a pretty good joke, right? Instead, this unlikely pairing means serious business, as Glenn Dickson and Bob Familiar demonstrate on their extraordinary debut collaborative album, All the Light of Our Sphere. The nine-track collection represents a deep collaboration between two musicians who share a philosophy of improvised music that moves, develops, and tells narrative-like stories.

Dickson brings decades of experience as a cutting-edge klezmer artist, having led the acclaimed avant-klezmer band Naftule's Dream and recorded for labels including Tzadik, Innova, and Rykodisc. His 2022 solo ambient album Wider Than the Sky established him as a practitioner of clarinet-based soundscapes, drawing comparisons to Eno’s Ambient series of recordings. Bob Familiar, meanwhile, has been a fixture in the Boston music scene since the early 1980s, serving as a synth player for bands The Dark, November Group, and Death in Venice before focusing on solo electronic compositions. Across 22 albums, Familiar transformed complex stories into immersive soundscapes inspired by works ranging from Cixin Liu's The Three-Body Problem to Kazuo Ishiguro's Klara and the Sun.

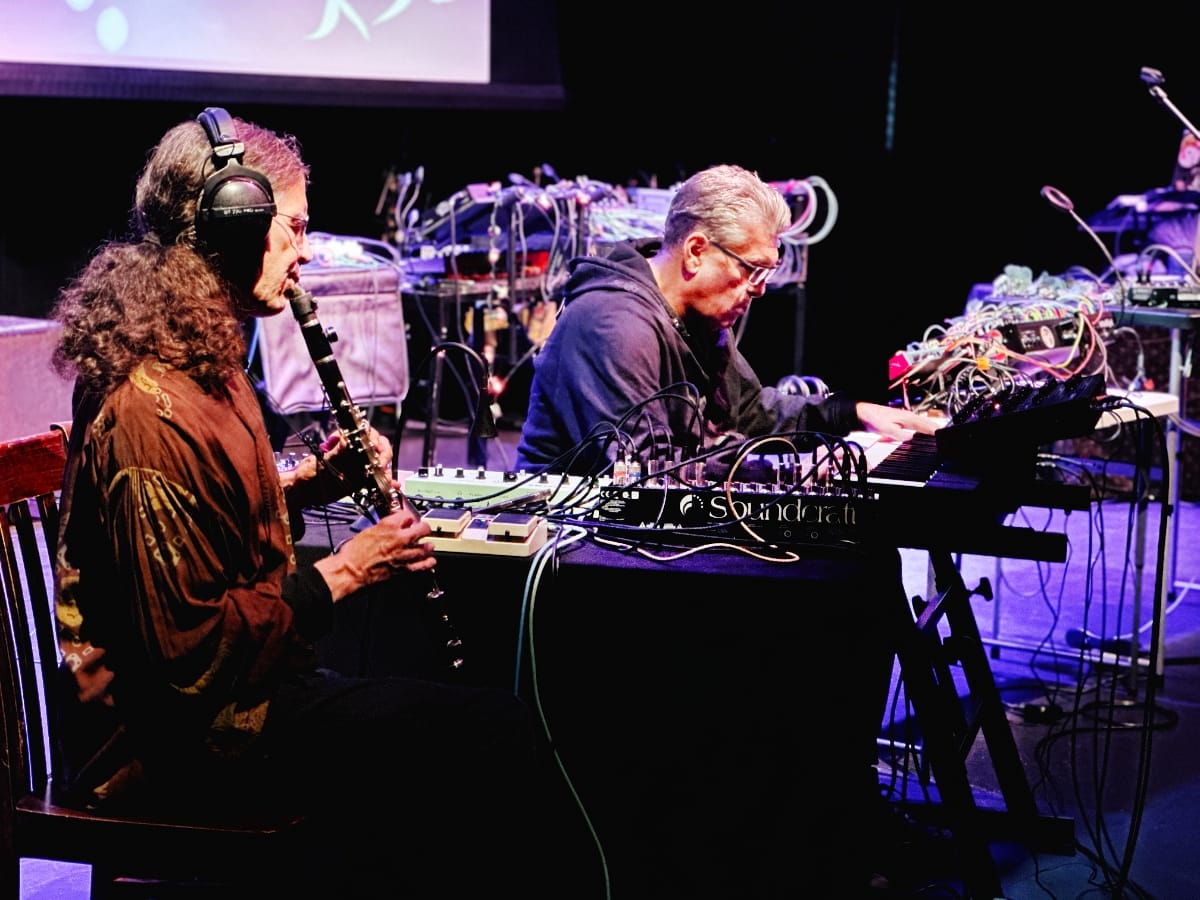

Their collaboration began in 2024 when both performed separate sets at an electronic music concert. Despite their different instrumental backgrounds, they recognized a mutual fascination with evolving loops and motif development. "It's an experiment. Everything's an experiment every time we get together," Familiar says. Both artists reject the static nature of much ambient and electronic music, instead incorporating melodic development, tonal modulation, and what Familiar calls "compelling story arcs." The resulting All the Light of Our Sphere layers clarinet and synthesizers to achieve what press materials describe as "a lush, orchestral sound that's also human and intimate." The album’s compositions are meditative, gorgeous, and diverse, from the watchful defiance of "When Fortune Laid the Trojans Low" to the tender resolution of "And Even Yours is Mine."

Host Lawrence Peryer recently spoke with Glenn Dickson and Bob Familiar on the Spotlight On podcast. They discussed the technical and philosophical foundations of their collaboration, the role of narrative in improvised music, and how two musicians from disparate musical backgrounds found common ground in their commitment to electronically textured improvisation.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for clarity, length, and flow.

Lawrence Peryer: Tell me a little bit about the origin story of the collaboration, specifically about the night that you and Bob met, and what it was about what he was doing that caught your attention.

Glenn Dickson: Well, we met at an electronic music concert. We were both on the bill—I played earlier, and then I heard him play. What he was doing was developing and moving forward, as opposed to many electronic things, which are somewhat stagnant in a certain way.

He was using loop processors that evolve rather than just stay in one place, which is what I also do. I don't just make a loop and stick on it. I'm constantly evolving, fading out old loops and bringing in new material. So the music evolves and has a story going on, as Bob likes to say. It goes from one place to the next.

After he played and we were hanging out, Bob came over and said, “We're doing similar sorts of things. Why don't we get together and play?" So that's what we did.

Bob Familiar: It was exciting to hear another musician who I felt was living in the same world I was. We were using different approaches—I was using synthesizers, while Glenn was using a clarinet—yet we were using loopers in a very similar way, creating these evolving textures and landscapes and then playing over them. It just seemed like it was ripe ground for digging in and seeing what we could do together and how that would sound.

Lawrence: You mentioned using loops. Do you mind lifting the hood a little bit and talking about when you're creating the loops to keep the music moving—are you doing that in real time?

Glenn: Well, for starters, I don't use an actual looper. I use a delay. I use long, long delays, so it sort of acts like a looper, but you can fade things out and bring new things in.

Everything we do, and I can speak for Bob too, we input things live in the spur of the moment. We deal with it live for our performances. And for these recordings that we did, there was nothing prerecorded, nothing added afterwards, actually. So what you hear is what we did in the moment.

I've been doing this for a while and have a pretty good sense of what I want to happen, how to make things happen, and how to correct things if they go awry or need to be changed. So it comes from experience.

Lawrence: The delay unit and any other sort of gear that you might be employing in the moment—you also have to have proficiency with those as instruments, it would seem.

Glenn: Oh yeah, and Bob's setup is more complicated than mine. You have to be used to working with it in the spur of the moment. You can't sit there and think, "Okay, what do I do now?" It's like, bam, you know, and you're playing and you're doing it while you're playing and making music out of it. So it's an extension of the instrument to a large degree.

Lawrence: Another element that comes up is the concept of narrative and structure. Could you tell me a little bit about the literary inspirations and sources that you draw on for creating improvised, story-based music?

Bob: I read a lot. I'm a hardcore science fiction fan, so I read a lot of science fiction or things where you're just on the boundary of more traditional literature. I enjoy that. That inspires me to take some chances and try to evolve my playing, so that it has some structure yet changes over time.

Technically, none of this is synchronized—we’re using loopers that are unsynchronized. As I input ideas into these, that’s another musician I’m essentially working with. So it's almost like another character in the story. So, I think, "Okay, what’s a motif now that might blend nicely with that and find some space to fit it in?" And all of a sudden, there are just these ideas floating over one another.

As Glenn and I were playing together, what thrilled me was that Glenn is such an amazing player. The way he structures his melodies is so beautiful. So, we’re both creating these underlying motifs that layer and float over one another, and they're not necessarily in time. So that changes itself, or that foundation is shifting, and Glenn is playing these beautiful melodies over top.

From the story perspective, that's where my ear saw the arc. It's really in the effort of mixing this, tapping into Glenn's playing, and just the way he evolves his melodies. That's where, for me and the way I listen to it, it's like, "Wow, that's where this whole story arc is coming from.”

Lawrence: Glenn, are you thinking narratively as you're improvising?

Glenn: I was just wondering about that. I'm thinking, "Okay, I just did this. What's gonna sound good next?" (laughter)

Bob: And he's very good at it. He chooses wisely.

Glenn: I'm just going along and thinking, "Here's where I am. Where do I want to go from here?" And when I listen back, I'm sort of surprised that it sounds coherent. I get into a zone where I’m just playing and making things happen, but I’m not necessarily conscious of it.

Part of my brain is like, "Okay, is this going on too long or should I bring something new in here?" There are a lot of things going on in your mind while you're playing something like this. That's why it's essential to have control over your technology, so it’s intuitive, allowing you to focus on your work without needing to engage another part of your brain with the technology. You're making choices, and they happen automatically because you know how it all works.

Bob: It just takes a tremendous amount of patience, I think, on both our parts. I'm listening to what Glenn is doing. I'm listening to what I've just generated. So now all of that activity is going on, and I’m being patient as that evolves, just not to start piling on top.

There'll be many times when we're performing live now that I might not do anything for a minute, a minute and a half, two minutes, because everything is there. It's like if I added anything, it would ruin it. I'm gonna let this ride. And then, when that starts to settle down, I'll bring in a new idea. So, I think patience is really critical to this kind of music on both our parts.

Glenn: We’re dealing with things that aren't synchronized, and also Bob's loops are generating sounds that are new and evolving algorithmically on their own. To a certain extent, you have to always listen to how things are evolving with the loops and the ideas that are already happening, and be careful not to overload the system. Be aware of everything that's happening.

Lawrence: You mentioned that there are no overdubs on All the Light of Our Sphere, and my understanding is that there weren't things like timers or click tracks. Could you talk about the philosophical or practical considerations that go into some of the constraints you chose to impose on your process?

Glenn: For me, playing the clarinet is a big choice. It allows for a certain expression, at least for me, having played for a long time. Additionally, on my end, the electronics are very simple, and I've explored them fairly deeply. So I feel comfortable in that.

And it is a limitation. I tend to limit myself technically to things that I can fully understand, rather than getting too advanced. I want to keep it entirely within my control.

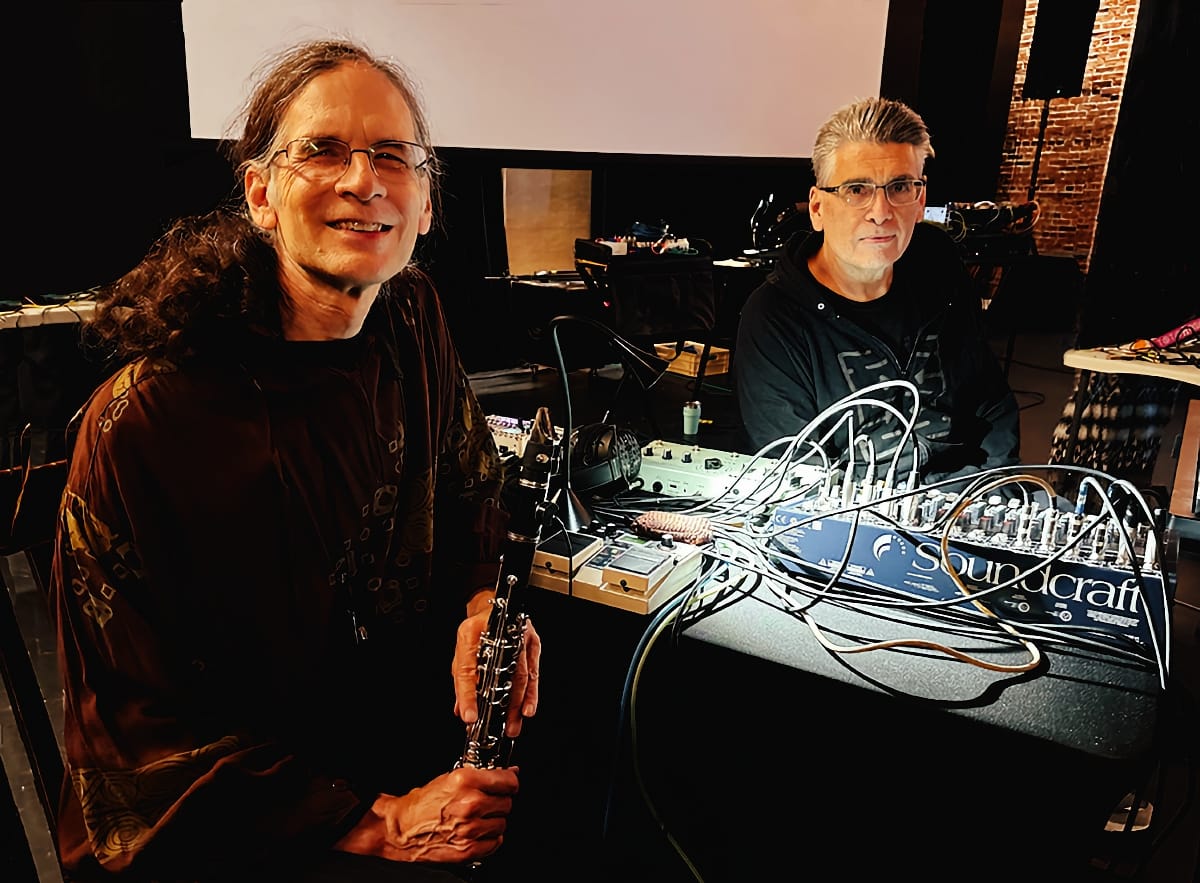

Bob: You mentioned a lot of the choices we made. I've got a lot of instruments. I have learned throughout the years of doing this that if I try to go, "I'm gonna use all five of these, these are my favorites, I'm gonna do it all," then nothing gets done. So I pare it down. Playing with Glenn, what I envisioned was that a Rhodes piano would work well with the clarinet.

That was one choice that went through its own looper and its own set of effects. But the other instrument is the Expressive E Osmose. This is a new type of instrument from Expressive E, where technology has been integrated into the keys themselves, allowing the keyboard player to be very expressive. There are multiple stages, as you press the key down, that are programmable. The key can also move left and right, and this movement can be programmed. So doing things like having a sound that might start clicky, but then speed up, and I can control the speeding up and the slowing down, or even more simply, just the brightness on a pad, and bring that brightness in and bring it out. But I’m controlling that through the way I play, rather than turning knobs or post-processing, or anything like that. So it allows me to be expressive in the moment.

And those were sort of the constraints. I said, "I don't want anything synchronized. We're not using a drum machine. We're not synchronizing the three loopers that we were using. We're just going to let them float free and allow ourselves to be expressive through the instruments we're playing."

Glenn: One more thing: it sounds like when you say, "Okay, I'm not gonna use a click track," that opens things up, and maybe too much. But for us, it's part of what removes the limit, which doesn't need to be there. Or that limit boxes you in to a certain extent. By not having everything synchronized, things float around, which gives them a more atmospheric feel and removes the boxes that a constant click creates.

Bob: And that's hard. That makes the playing and the performing harder. You have to be, as I said, very patient, and you have to listen well so that you’re not clashing; you introduce ideas gently and purposefully, as the moment arrives when "Okay, now's the time to bring this in."

You have to work hard at that when you're not using the tools in the studio to allow you to say, "Oh, you know what, we can go back. I can just clip that out and we can overdub a new part right in there." That's a great thing to be able to do, and I've done a lot of that in the studio. But for this, it just felt like, let's challenge ourselves in this way and see what happens.

Lawrence: How did you go from these studio sessions to finding the actual compositions within them?

Bob: We played together, I think it was April of 2024, and I believe by May or June, we were in my home studio here, and we just set up, started rolling, recording after getting levels, and we just started playing. We ended up playing for like two hours the first time. Recorded everything.

I went back and pulled out some parts, then shared them with Glenn. I said, "Hey, this is sounding pretty good." We made another scheduled get-together. We got together four times. We had about eight hours of material after all of that. All improvised, but at the end, what was cool was to find these moments that just felt like compositions.

I was like, "Wow, this is cool." The way that this evolved, if we start here and we end here, as Glenn pointed out, there's a story arc. There's a beginning, there's a middle, there's an end. Beautiful melodies, beautiful changes. So we concurred and ended up with about nine tracks in the end.

Glenn: Well, one thing that just occurred to me as we were talking about this is, you know, Miles Davis used the same process when he was doing In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. They were just jamming in the studio, and then they cut it all up and made tunes out of 'em. So it's sort of a similar process.

Lawrence: Tell me about the title track, "All the Light of Our Sphere." It’s both the album title and a track on the album.

Bob: I think what's important to know is how the names of the tracks were chosen. I'll let Glenn tell that story.

Glenn: So I often do this or have done this before. I look through poetry books and pull out lines that I like or little phrases. "Oh, I love this for this." And so I just pulled off a translation of Dante’s Inferno. I was going through and pulling out little phrases that I liked. I made a whole list.

Then I listened to the tracks and said, "Oh, this one goes with this one, this goes with this. This feels like this." So I just sort of matched them up that way. I liked the sound of the words, and I thought the feeling matched the sound of the music.

As far as using that one for the title track, I just liked the expression and the luminous quality of it. It goes with the cover photo on the CD. It just felt like the right phrase to sum up what we were doing. It's not that that particular track summed up musically what we're doing, but I wanted to have a title that sort of expressed what the album was about.

To me, the titles, especially on instrumental tracks, give the listener a direction or a feeling that's helpful, maybe, for a listener to have. And so they're not necessary. We didn't talk about the titles before we played. We just played.

A lot of electronic music concerts have visual components to them, where visual artists are doing moving visuals while you're playing. And that's not necessary either, but it helps some listeners focus on the music or create a vibe that helps them get into the journey, so to speak.

Bob: I thought that the titles that Glenn chose were just perfect because the music itself is very poetic. And having the titles drawn from great poetry, I was like, I was all in on that. (laughter)

Lawrence: Bob, I'm curious about some of the broader work you do in the electronic music world. It's such a deep vein. Could you talk about the tradition and where this project might fit within the universe of electronic music?

Bob: What drew me to electronic music is I loved that it seemed to bridge engineering and art. And I always liked being in that space. So I went to school as an engineer, but I've been a musician my whole life.

And when electronic musicians get together, we're talking as much about our gear and who manufactured it, as well as what technology is used. Such as it’s based on Bob Moog's design, or this is a Buchla design. It's an ARP, or whatever it is. So the personalities, the engineers who created the instruments, are the rock stars, I think, in that world as much as the people who even play the instruments. That's kind of the tradition for me.

Then you get drawn into not only commercial music or jazz where these instruments are being used, but also, because of the engineering aspect of it, you find yourself drawn into the very experimental side that is so critical, I think, to electronic music and the influence it has had from the classical composers who adopted electronics in the forties, fifties, and sixties and started to compose pieces just for electronics.

I would be remiss if I didn't mention Brian Eno. When I was at Berklee in the late 1970s, I felt somewhat alone, as I was the one listening to Brian Eno, while everyone else was listening to Asia and Steely Dan. But I was like, I'm gonna put on Before and After Science or Another Green World. That to me was exciting, and that was the direction I wanted to go in.

And of course, there’s the work he did with Robert Fripp. I was always a fan of King Crimson, and the looping machine I use is based on the work that Eno and Fripp did when they were connecting tape machines. So that is undoubtedly in my roots.

Lawrence: Listening to you, one gets a sense for the versatility of those instruments. They show up in so many contexts. But you are doing that as well, Glenn, with an instrument that comes from its own specific tradition. Did you always know the clarinet was this versatile of an instrument?

Glenn: From the time I was in college, probably. I went to New England Conservatory and heard a lot of the clarinet being used in a lot of different ways there. Just being exposed to all the klezmer and the Balkan and the Turkish music, and then also early jazz—the fluidity of their pitch and tone that they were using. I began to realize that the clarinet was capable of many things.

To be honest, I also came out of Robert Fripp. When I was a kid, I went to see him play during his Frippertronics tours, which featured two tape decks and everything, and that just blew my mind. And it wasn't for like another twenty years that the equipment sort of evolved, that I could do it on a clarinet, a similar kind of thing using just a pedal and a pickup mic. As soon as that happened, I was like, "Yeah, I'm gonna do this." That was a formative experience for me, hearing Robert Fripp and that musical technique. It didn't matter that he used a guitar.

As far as evolving, I'm starting to explore. I love the clarinet sound too, and I didn't want to mess with it too much, but I’m starting to experiment with the sound a bit now, using distortion pedals and guitar pedals on it more, just to vary it, for musical variation and certain situations. I’m trying to make it something that makes sense to me or that I imagine, rather than just doing things randomly. (laughter)

Check out more like this:

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmGarrett Schumann

The TonearmGarrett Schumann

Comments