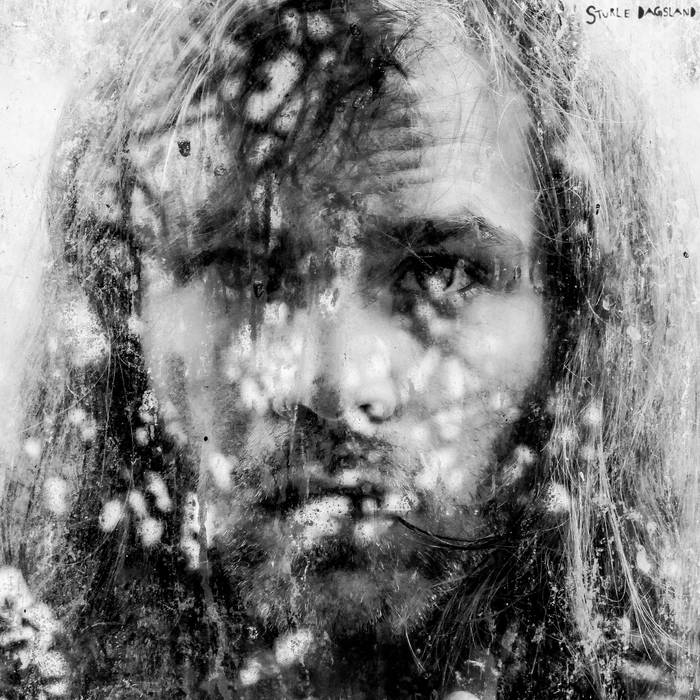

Sturle Dagsland is one of Norway's most acclaimed and genre-defying artists, known for his wild, captivating performances and astonishing vocal range. Sturle and Sjur are siblings based in Stavanger, Norway, and the creative force behind the project. They fuse Sámi folk influences and instruments from around the world—Nordic folk staples like nyckelharpa and goat horns alongside Chinese guzheng, West African kora, Hungarian cimbalom, and waterphone—with modern recording techniques and an experimental ethos. From performing alongside halling dancers to recording with choirs of sled dogs, their work is as adventurous as it is deeply rooted in heritage.

Sturle Dagsland released their self-titled debut in early 2021, earning one of the prestigious Edvard Awards for best Norwegian album of the year. Their long-awaited second album, Dreams and Conjurations, mixes avant-garde pop, screaming metal, folk music, and immersive electronic soundscapes. In this interview, Sturle and Sjur Dagsland discuss the traditions, personal rituals, and experiences that inspire their compositions, their approach to foreign instruments, and what it's like to collaborate as siblings.

Arina Korenyu: Your music blends traditional influences with modern experimental sounds. Do you see yourself as being more rooted in the past or more oriented toward the future?

Sturle Dagsland: I think it's really a mix of both. We've always been fascinated by folk and traditional music from around the world, and that definitely plays a big role in what we do. At the same time, we're very interested in new technology—exploring different recording techniques, experimenting with modern approaches, and pushing boundaries.

So, it's difficult to say we lean entirely one way or the other. It feels more like a symbiotic relationship, where the past and the future work together in what we create.

Arina: For those of us outside of Norway, could you share a little about the Norwegian traditions that inspire your sound?

Sturle: Yeah, so we draw a lot from Norwegian folk music, and in some parts of my singing, I incorporate my own interpretation of those traditional vocal styles. It's not a strict imitation but more of a personal way of carrying that sound forward.

For example, we've experimented with something similar to kulning, which is a traditional way shepherds in the mountains would call out—yelling across the landscape to gather and guide their sheep. You can hear echoes of that in some of our songs, like "Whispering Forest, Echoing Mountains." It's a kind of vocal tradition that we've tried to bring into our music.

We've also used a lot of Nordic instruments. One of them is the Swedish nyckelharpa—it's a bit like a fiddle, but instead of just strings, you press keys, and there are sympathetic resonance strings underneath that create this rich, layered sound. Another is the Norwegian goat horn, which has a fascinating story behind it.

I actually got mine from a master craftsman in Norway who's well-known in the folk music world. I just sent him a message, not really expecting a reply, since I had read there was a two-year waiting list. But then, out of the blue, he wrote back: "Yes, I have a goat for you."

That's because he not only makes the horns—he also tends the goats himself. When a goat reaches the right size and the horn is in perfect condition, it can be used to make an instrument. From what I've seen, the goats live good lives until then. So, quite literally, the music we play carries a very real connection to the animals and the land.

In that way, it's not just about instruments, but also about traditions. For example, one of our songs is called "Hallingen," named after the Norwegian folk dance. It's like Norwegian breakdance. Dancers spin, flip into different positions, and jump as high as they can to try to kick a hat off a stick.

A few years ago, we were invited to perform at a museum opening with a halling dancer. For that occasion, we created a piece in the right halling tempo so it could work for the dance. Later, a well-known Norwegian fiddle player challenged us to keep exploring this idea, reminding us that as long as we stayed true to the tempo, it could still 'belong' to the halling tradition—even if no traditional dancer would call it a pure halling.

The song grew from there. It's not a traditional halling, but it carries the energy, rhythm, and spirit of one. We also drew on our Sámi heritage—our family is from the north of Norway, and Sámi traditions are an important part of our identity. Elements of Sámi vocal style and rhythm found their way into the music, blending with the Norwegian folk inspiration to create something new.

Arina: "The Ritual" was inspired by a ritual you once participated in. Can you tell us about that experience?

Sturle: A close friend of mine had been struggling for years with both psychological and physical issues. He had tried everything—from hospital treatments and traditional therapy to more spiritual approaches—without finding relief. Eventually, he came across a medical study in Norway based on a real scientific method: transplanting healthy gut bacteria from one person to another. The idea is that if you take the flora from someone in perfect health, it can reset and take over your own.

He participated in a hospital study but didn't know whether he'd received the real treatment or a placebo. He asked himself which friend might be healthy enough to help. Because I don't drink alcohol or use drugs, he thought of me. He even showed me a list of the 'ideal donor' traits—basically Michael Jordan at eighteen, in perfect shape.

I agreed, but only after thorough testing. My sample was sent to a laboratory abroad within twelve hours, frozen, to ensure it was safe and free of diseases. Once everything was cleared, I helped him with the medical part. But he also asked for something else: a spiritual ritual to accompany the procedure. He believed he needed healing on both a physical and spiritual level. I loved him and wanted to support him, so I agreed. He gave me full freedom to create a ceremony.

We met at midnight. He began by confessing everything that had been weighing on him, to clear his mind. Then the ritual began. I blew a cow horn and told him that until I blew it again, he would follow everything I said, like entering a state of hypnosis.

I moved into a kind of performance mode, using throat singing, deep guttural sounds, and drumming. He stripped completely, and I brought out symbolic elements I had prepared: I mixed a few drops of his blood with mine, added tears from a friend, bones, 'to help him grow out of the hell he'd been in,' and feathers 'to give him wings.' Each element had its own meaning, woven into a long speech and ritual.

Arina: Your album features many different moods—from the haunting ambience of "Windharp" to the joyful energy of "Whispering Forest, Echoing Mountains." Do you see the album as a kind of narrative or more as a collection of distinct visions?

Sturle: For us, every song has its own vision, but at the same time, the whole album is connected. It has many moods, and that's intentional—because life itself isn't just one mood. It would feel unnatural, and even a bit dishonest, to limit ourselves to a single feeling or a single genre.

We're not the kind of band that just plays one thing, like straight rock and roll. Instead, we allow ourselves to move through different emotions and atmospheres. Still, there's a red thread running through all the songs. It's like reading a book: each track is its own chapter, a different episode or adventure, but all of them are tied together by the same underlying intention.

Arina: You've recorded in places as unusual as abandoned ships, remote villages, and stormy clocktowers. Do you feel the environment imprints something onto the music?

Sjur Dagsland: Yeah, some of the songs were written in this really beautiful water tower in Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin. The place has this amazing long reverb, and it just inspires you to play differently. When we're jamming there, something kind of magical happens—the space affects the way we play, and we end up doing things we probably wouldn't do anywhere else.

Sturle: We travel a lot and tour a lot, and if we're in an interesting location, we'll sometimes spend a few extra days just to see if we can capture the sound of the place. That could be the ambience, or we might record something specific right there.

For example, this wasn't for the current album, but for our last one, we were in Greenland in a small village with sled dogs—about two hundred dogs from different packs. We went into the middle of the village and set up microphones so that all the dogs could become, in a way, a choir. I was in the center, making different sounds, seeing how they would react.

At first, it was just howling, but after a while, they started responding to what I was doing. I ended up feeling like the conductor of a two-hundred-dog choir, almost like I became the alpha. When I started howling, they howled. When I acted more like a dog and suddenly stopped, complete silence fell over all of them. It was a really magical moment—recording it, but also just experiencing that connection between the animalistic and the human voice.

Also, for this album, one of the songs [“Whispering Forest, Echoing Mountains”] came from a trip we took while touring in China. We were just walking around the narrow streets near the Forbidden City in Beijing when we met this old, half-blind man. He really liked us and invited us to his home. There, he showed us guzheng—a traditional Chinese instrument. It wasn't the same one I later bought in China, but that experience inspired one of the instruments we used most on this album.

He had never been outside China, but he told us he'd dreamed of the Norwegian mountains and really wanted to share that dream with us through his music. We ended up jamming with him all night, and his family even brought us dinner.

A couple of years later, when we went back through our recordings, we realized that experience could become a song. Even though the final track wasn't recorded there, that night and that connection with him was the inspiration.

Arina: In today's conversations about cultural appropriation, how do you approach using instruments like the West African kora or the Chinese guzheng into your music?

Sturle: When you meet an instrument maker, they're usually really happy to see their instruments being played. Most of the ones I know want their traditions to live on; they want their instruments and music to be spread around the world. They're especially happy when musicians actually use the instruments, not just hang them on a wall.

Sometimes, skeptical people will ask if you are a musician, and when they see that, they're fine with it. For me, it's about using the instruments in new ways. For example, the way I use the guzheng doesn't really sound traditional at all—I just explore it in all sorts of ways.

It's the same approach we take with all of our instruments: it's about having fun, experimenting, and spreading the joy of music.

Arina: Do you have any advice for the person who wants to become a multi-instrumentalist as well, on how to approach an instrument that's completely unfamiliar?

Sturle: It's not like we're masters of every instrument. We play a lot of different things, but the approach we take is simple: you don't need to be the world's best at everything. You can just have a playful approach. There's nothing wrong with not being technically perfect—you can still find ways to use an instrument in your own way. For us, it's just natural to keep expanding and exploring different instruments.

Sjur: Once you know one or two or three instruments, it becomes much easier to learn another. You start to listen more closely—to the timbre, the acoustics, the typical phrasing, and how the instrument is usually used. That awareness makes it much easier to pick up something new.

Arina: Is there any instrument that is still on your bucket list?

Sturle: Yeah, I have a few, especially the expensive ones (laughter). I've been talking to an Italian church organ maker—he makes these really beautiful portable organs in his spare time. Back around the 1300s, it became a small trend to make these little organs you could carry around and play classical music on.

They use an air blower and usually have about two octaves. You can carry the portative organ with its pipes, and they sound wonderful. The only problem is they're expensive and not very easy to travel with, so I could probably only use one if I were traveling by car. We usually travel a lot by train, so it would be pretty difficult to bring it along.

Arina: Your voice is such a central force. How do you protect it? Is there a discipline in how you prepare yourself before performing?

Sturle: I try to stay healthy. I eat well, stay in shape, and do a lot of yoga. On top of that, I always do vocal warm-ups. It's really about constantly trying to expand the voice and stay in shape—kind of like training for a marathon or any other sport.

Sjur: Yeah, I was just thinking about the exercises—it's really a twenty-four-seven thing. Sleeping in the same hotel room as my brother, you have to deal with a lot, including waking up in the morning with vocal warm-ups . . . but he has to deal with my snoring, so it is all fine.

Arina: How is it spending so much time together and creating music as siblings? Can it also be a source of tension sometimes?

Sjur: Yeah, in some ways it's easier to get along with your brother, because you can have those big discussions and then just forget about them afterward.

Sturle: I think after we stopped living together, the tensions were less.

Sjur: We used to have a studio in a very small room, which was also my bedroom. Sturle would sleep in the bed, and I slept on the floor. We were sleeping, eating, and working all in that same space, and it was pretty intense. Fortunately, now we live separately.

Sturle: Now we only live on the same street.

Arina: Do you always perform as a duo, or are you planning to expand with other musicians or collaborators for the upcoming tour?

Sturle: Usually, in the last few years, we've only performed as a duo—unless it's a special occasion where we collaborate with a dancer, visual artist, or something like that.

We have done shows with up to five people, and that usually means inviting friends like us—people who play different instruments and are willing to challenge themselves by using things they're not used to. But most of the time, it's just the two of us. We bring whatever we can carry and try to make the best of it.

Arina: Looking beyond Dreams and Conjurations, what dreams or directions do you see for your music in the coming years?

Sturle: We're going on a tour in Europe in October and November, and next year we'll do more shows in Europe, plus trips to Japan, Korea, Mexico, and Brazil.

Looking ahead, we'd love to collaborate with a fantastic director to make a musical. That would be really fun—but it would need to be a big production, like hundreds of millions. I'd do the voices for all the different characters, kind of like Muppets, and sing in lots of different styles. It would be this surreal, fairytale-like mix—something really imaginative and playful.

Sjur: I would be on a flying carpet.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments