The string quartet has been a central instrumentation for expression by composers throughout Western music history. From the contributions of Haydn's restrained style, the mysterious late Beethoven quartets, the rhythmic grooves of Bartók, the ultra-expressivity of Shostakovich, the sound explorations of Lachenmann, the hours-long late pieces by Morton Feldman, the compelling work of Caroline Shaw, the iconic "Many, Many Cadences" by Sky Macklay, and the ghostly String Quartet No. 2 by Jürg Frey, the string quartet has been a primary medium for composers to showcase their perspectives for hundreds of years. How does one write a string quartet given the weight of so much history? I composed one string quartet in 2012 as a graduate student, and I'm still more or less terrified of them.

Kory Reeder's work Homestead (2024) is a nearly hour-long contribution to the subgenre of the string quartet, composed for Simon Reynell and Apartment House. Referencing the classical and romantic-era sonatas for string quartet, the work is split into four movements:

I. Hymns: from a dog-eared book found in an unmarked box

II. Sonata: from preserved quilts and fabrics

Interlude: Pax Americana

III. Rondo: from several fragile plate negatives

IV. Waltz: from a handwritten fragment

The movement titles deviate from classical-era quartets in their order and content. Usually, a sonata movement is first, followed by a slow movement, then a scherzo, waltz, or rondo, and finally a faster movement. However, it can be difficult (though not impossible) to find the traditional structures in Reeder's composition. The result is a highly individual work that pays homage to the history of the medium.

The first movement of Homestead ("Hymns") alternates solo instrumental sustained tones with interjections of expressive tonal chords (diatonic "white key" chords, seventh chords, ninth chords, quartal and quintal chords). This creates a shifting blend of colors as if passing moments between stable harmonies in a hymn are slowed down and left to develop on their own. There are quite open-sounding harmonies that don't so much progress as rotate, like a moving object throwing off different qualities of natural light. There is a really clever use of held chords that have instruments alternating their bowing, creating a sense of movement within musical stasis.

The second movement ("Sonata") does not sound like a sonata on first listening, but upon detailed examination, one can find a sonata-type structure at work in the music. There is a slow drive in this movement, a faster tempo than the first movement that still has a reflective mood. The harmonies and phrasing remind me a bit of the tradition of early American Shape Note/Sacred Harp singing, colors passing quickly into a kaleidoscopic, multilayered texture.

The interlude ("Pax Americana") for solo plucked cello sounds, quite on purpose, like someone strumming the instrument on their porch at night, which is how the movement was composed by Reeder. The movement is mainly focused on a G9 chord stacked in fifths (F-G-D-A) in the middle-low range of the instrument. There are compelling rhythmic variations and notated silences between playing, similar to the compositional techniques of Morton Feldman.

The third movement ("Rondo") mostly sounds like it's concerned with harmony and resonance, with chords bowed together as an ensemble, subtly contrasting with more sparse harmonies of duos and trios. The fourth movement ("Waltz") contains some of the most sensitive and unified performing by Apartment House—a showcase of their ensemble musicality. We have a gently moving waltz mixed with the static chords from earlier movements (especially the first and third). It feels like moving in and out of a dance with multiple melodic lines and counterpoint coming together into a woven texture.

The album is a sonic image of its inspiration, the sensation of wandering the wide-open spaces of the Nebraska plains. Reeder has been unphased by the significant literature of past string quartets and strikes out on his own, quiet and deliberate. Kory Reeder spoke with me from his home in Denton, Texas, where he was recovering from multiple tours. We discussed the distorted legacy of Western art music and his creative process for the work.

Writing a Lot of Music

Chaz Underriner: You are a very prolific composer. I count that you've written 163 pieces since 2014 [14.8 pieces per year on average], and that's just the pieces listed on your website currently. There may be others that aren't there.

Kory Reeder: I'm a real big believer in thinking about pieces having relationships and writing in series. If you read my dissertation, I have a huge section on writing in series, and the Wandelweiser collective is important for that because some of these composers have collected series of pieces.

Antoine Beuger has his pieces for increasing the size of ensembles like octets all the way up to twenty players, and all these pieces are quite similar in how they work. They have variations in technique, and they're not exactly the same piece, but they share a core conceptual value of an iterative process, of doing something again and again.

The Wandelweiser collective is probably the only cohesive group of composers, even if their aesthetics are slightly different, that all kind of share that and will try doing like a series of things over and over. I've always been interested in visual art, and I think Feldman's music is clearly heard as an influence in mine, especially when I was an undergrad. His relationship to visual art was always super interesting, either just socially or as a friendship, or more direct things. I read this pretty wild paper about how the piece Rothko Chapel is very similar to the building in its formal design. One thing I kept seeing with my interest in visual art is directly mapping concepts or formalizing how the construction works between music and a piece—it always felt okay, I did that, and that's the end of it.

But with visual art, there's this iterative process of doing things again or having a very clear visual aesthetic or a very clear visual relationship that's iterative. So like we mentioned Agnes Martin—these grids—or Mark Rothko: it's a Rothko when you see it, just based on the identity of the thing itself.

All of these pieces stand alone, but they're related to each other as a series of relationships. Like my Grid series of pieces, I have a dedicated section for the grid pieces because there are so many of them. It was a fruitful way of investigating a bunch of ideas in an accessible and ready-to-go way.

I've been interested in improvisation scores and experimental music practices, but I'm still so attached to harmony. So I was trying to find these ways of interacting with a super open way of making music that still has the harmonic palette that I like, trying different ways of accessing that and getting into that. So my grid series is like these networks of pitches that you can move in any direction, and then scores that kind of give the invocation of how you access the material. Some of them are declarative.

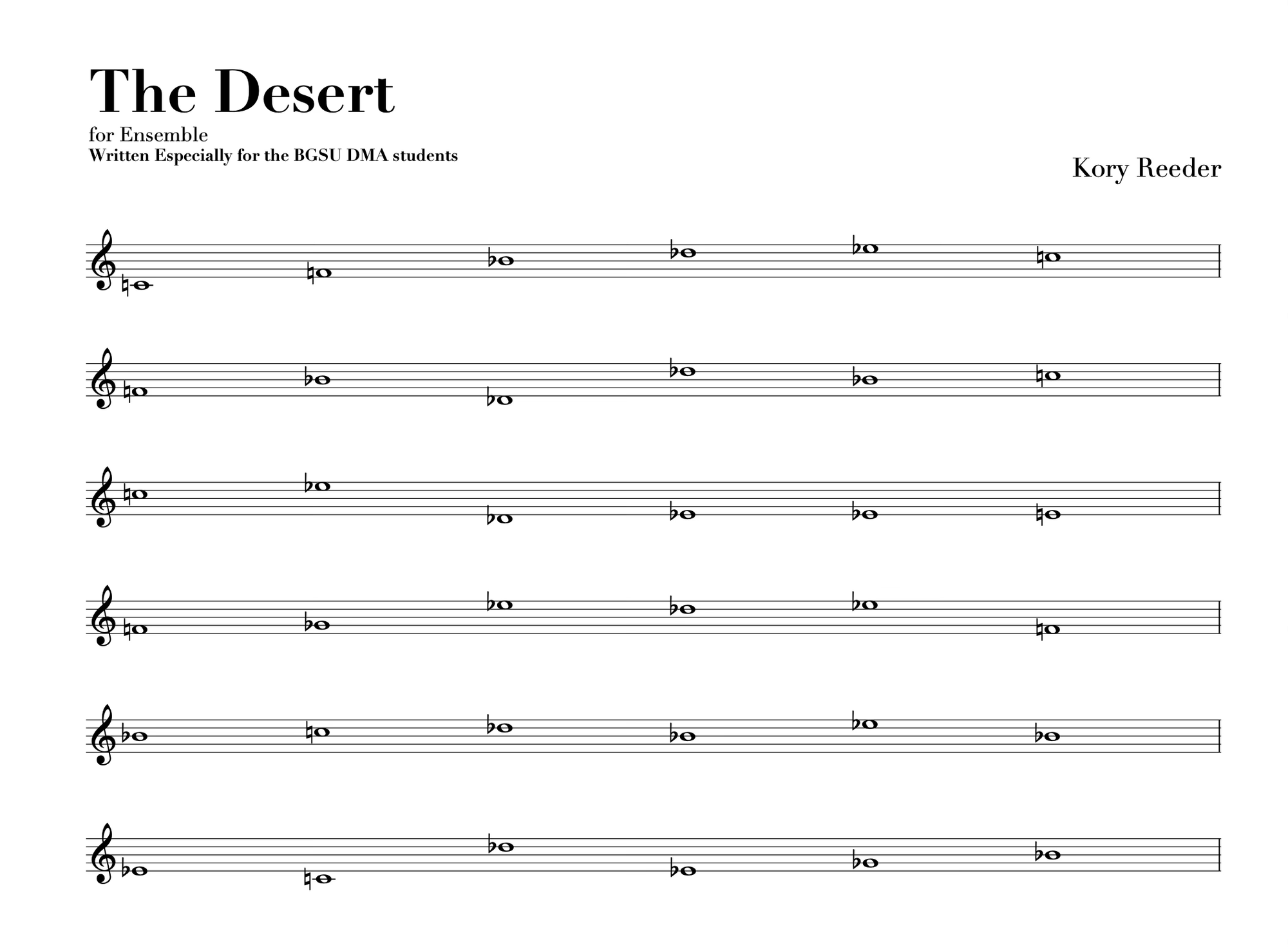

This piece, "The Desert,” has two groups of performers: attackers and sustainers. So you can think about piano and violin in a really broad sense. Then they have their own rules. So if you're a sustainer, you're doing long tones. And if you're an attacker, you're playing small, fragmented gestures that are very declarative, and that's much more explicitly described of what you do.

But then, as that series developed, I got increasingly into poetry and poetic prose scoring. So some of the text for the later pieces in that series is quite poetically open, quite implied rather than explicitly notated. But that helped me generate a ton of music because it's like capturing an aura of a piece rather than just dictating the idea in your mind and letting it flow.

So I wouldn't be sitting there grinding out this idea of a piece that I had in my mind. I was finding a way of accessing that same aesthetic, that kind of hazy sense of what the piece is, rather than trying to recreate it in explicit notation—in writing a fully notated score. A piece like Homestead is completely notated. How can I access that sound world in a way that embraces the free improv that I'm interested in with poetic text scoring, but still has the harmonic attachment that makes it sound like a piece by me? And doing that iterative, serialized, series-based composition produced a ton of different pieces quickly.

So my catalog is honestly a little bloated in that sense, because I took that idea of series—these are related pieces—and expanded it into a bunch of different things. So there are concepts, there are ideas, there are direct quotations in several pieces where I'm redeploying ideas in a lot of different ways.

Relationship with Recordings

Kory: That's the benefit of being at a place like UNT for doctoral studies and having access to a billion performers. If I had an idea or wanted to try something, I could record it immediately instead of waiting for a student recital or something like that—just do it myself. A lot of these pieces have never been performed live, but we recorded them. I'm not particularly precious about that either. More people are going to listen to a piece on my Bandcamp page than are ever going to see us live. Especially in the twenty-first century, that's how I discover music.

I'm from the middle of Nebraska. I'm probably never going to see a Klaus Lang piece live at a show that I'm not involved in in some way. But that didn't change the fact that he's a super important composer to me. Or the entire Wandelweiser catalog or everything on Another Timbre—it's some of the most important music in my life that I'll probably never see or hear performed, but that has no change in my ability to engage with it and interact with it. Especially millennials of a certain age downloading shit off Limewire is how we interacted with a lot of the music that we really like. That doesn't take away from the importance and value of a live show. But I figured that if nobody’s going to be at these concerts anyway, I have the ability to do high-quality recordings, or at least passable recordings, of things that I can do myself, and more people will be able to engage and listen to it anyway.

Chaz: So the relationship to recordings is as definitive objects that are an idealized representation of the piece, recognizing the potential of it in a defined way as opposed to live performance? That's a relatively new practice—people composing for albums or recordings rather than live performance. I relate to that too, because when I fell in love with music, it was listening to stuff on the bus on the way to school.

Kory: The contemporary classical music world is very strange. I'm not even convinced that many people in the contemporary music world even listen to this music on their own time. Are you actually into this? Or is this just your performance practice? Which is fine, but then it enters a somewhat archaic mode with how people learn about this music and how they’re educated within academia to engage with it. This places so much emphasis on the recital mode of presentation—and especially the academic ivory tower kind of recital mode—that it neglects various other modes of engaging with the material.

A lot of times with recordings—I run a record label (Sawyer Editions)—I know what these numbers look like. Not a ton of people in the grand scheme of things are listening to contemporary classical music on their own time. And not understanding that you can have a house show, you can play at a gallery, you can play at a bar, and that does not diminish the value of any of this. But it can operate in several different modes. I think the way classical music is a death cult frames that in a very archaic sense of "this happens here on this stage" rather than in your headphones or at a bar or anything like that.

There's a hagiography of everything, and then people are trying to make their own hagiography because that's what they've been taught about the artists that they love. I didn't come from that background. I came from a punk and DIY background where you cut a record and put it on the internet, and maybe twenty people would listen to it, but at least those twenty people weren't your friends at the house show.

Chaz: Your mode of production and connecting with audiences is outside of this formalized framework of the recital of classical music? Presentation, dissemination, etc.?

Kory: Yeah.

Chaz: That's what I'm curious about with Homestead. How does that work for you when you're composing for an ensemble like a string quartet and you're composing for an ensemble like Apartment House that plays at really prominent classical music venues like Wigmore Hall in London?

Kory: More than anything, I wasn't even thinking about that. I was thinking about I'm writing this album for the label Another Timbre. I'm writing for an album, so the live performance isn't crucial. It just happens that the way I write is very performable live.

So, it’s not as if I’m going to write it in a way that can never be played live. The way I think about it is: How does this work as a record? How does it work as an album? And in the same way, how does it work as a live piece?

It was written for this release, and that's what Simon Reynell pitched it as. He emailed me asking if I had string chamber music and if I'd be interested in doing another album. Another Timbre is my favorite label, and Apartment House is my favorite ensemble. I just asked him, "What if we just did something new for a new album?" And he was into it. So what do I want it to be? And I went traditional with it for a myriad of reasons, but fundamentally, I was like, "Okay, it's going to be an album, so I have about seventy-five minutes. That's how long this can be. How do I want to break that up? How do I want to deal with it?"

Just having that initial framing was one way of doing it. And then the other was, "Okay, this is going to be an album, and I want it to be a single, unified artistic statement." I don’t want it to be a compilation of random pieces. I don't want it to be just "here's all my string quartets." Simon and I talked about string chamber music, especially string trios. Jürg Frey had just put out his String Trio on Another Timbre, and it was coming off the heels of that, even though these albums were released two years apart. Jürg had written this forty-five-minute-long string trio. So I think it just had it in my mind, and because we were talking about string chamber music, I just started thinking about string quartets. There's this weird aura around string quartets.

I had a professor back in the day—not Tony Anthony Donofrio—who was talking about how there's a lot of pressure with string quartets because every great composer has a great string quartet, which I think is part of the death cult that I mentioned earlier. I don't think that's peer pressure from dead people. Just because every great composer has a great string quartet, that doesn't mean your first string quartet needs to be anything special. At this point, I think Homestead is my seventh string quartet, sixth or seventh. So I'm over that shit and I don't care about that.

However, I was interested in the concept of a string quartet as a flag in the ground, marking "this is something that I'm doing right now." Rather than thinking about it as "this is the best piece I'm ever going to write," I wanted to try more traditional things because I was, at the time, starting to teach form, analysis, counterpoint, and ear training. So I was revisiting a lot of stuff that I didn't care about before and thinking as an adult, "What can I do within this kind of space?" So the whole string quartet in four movements, whatever. What can I do with that that would be interesting?

Peer Pressure from Dead People

Chaz: I'm curious about this peer pressure from dead people thing. One time, I was talking with the composer Emily Koh, and she mentioned basically that it's a waste of time. Why would I use my mental energy and my personal working time to compare myself to a dead person or the work that came before me? To her, it just didn't seem useful to be in that headspace.

I feel like you're saying something similar, but I'm curious if you could unpack the "peer pressure from dead people" a little more, because in a medium like acoustic music composition, it's kind of a given?

Kory: So when I call it a death cult, obviously that's a little bit tongue in cheek, of course, but it comes from the hagiography of especially Germanic composers like Beethoven, Mozart, et cetera, who are touted as monolithic figures that have transcended their human quality into titanic demigods, or whatever Greek or Roman mythical metaphor you want to throw at it. A Herculean quality.

It goes into the academic zone where so many of us learn about this stuff—how much attention is given to this handful of composers that we are immensely preoccupied with talking about and performing and engaging with on levels that we're not going to with other people. It's easy for a culture to get railroaded into a pretty repetitive cycle. And then with 250 years of that happening, the cultural inertia is really intense.

Chaz: And you have people trying to rewrite a new version of a Beethoven quartet or whatever...

Kory: And that's been a thing for 150 years, or 250 years—people having the pressure of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Mahler didn't even call his a ninth symphony because of this. I hear stories like that, and I just think they're ridiculous. There's this cultural perception of what writing a symphony is that changed with Beethoven, and so much so that it paralyzed some people from getting close to a ninth symphony.

It’s really weird and makes me uncomfortable because it treats people like they’re not people anymore, while also putting a level of pressure on your work that I think is arbitrary. Especially in 2025, it feels almost immature in a way. It's naïve and almost arrogant because our space in the culture at large right now is very small. Nobody gives a shit what we composers are doing in the grand scheme of things, especially in America. You can take that and have some doom and gloom, and that can be horrifying.

It's like the National Endowment for the Arts right now, to get political. That stuff is horrifying. But as far as what that means for what we can make and how we can frame our sense of our creativity, I don't look at that and get scared. I do for the National Endowment for the Arts, but I'm talking about the peer pressure from dead people. I look at that and it doesn't freak me out. I find it liberating because it's like, "Who cares if in the grand scheme of things, not a ton of people are particularly concerned with the tradition that this music comes from? Then why should I be?"

Especially in the internet age, and especially after John Cage, you can do whatever you want, and there's a way for people to find a context for it. Just look up the most obscure tags you can find on Bandcamp, and you can find some pretty wild shit. But you can still have a context of where this comes from and understand that this is part of a bigger ecosystem and a bigger cultural context and sphere.

Even if it's super niche, there's probably a subreddit for it. There is a community for it, and a group of people who are interested in it. So that opens up a lot of possibilities for being able to explore and try a ton of different things without having to be particularly freaked out about alienating people.

Even if you're doing some crazy, unethical, not good stuff, people can look at it and be like, oh, it's like GG Allin. Or there's a relationship that can be built because we have access to all this history and material, and with the internet, we can research and learn more. Like "I've never heard of 'blackened hardcore,' what does that mean?" And then go down the tagging rabbit hole of finding out there's an entire aesthetic world that's like that, which I find exciting. Because then you can try things without worrying that they’ll be completely out of left field.

So when it comes to writing my string quartet, for example, feeling this peer pressure from dead people, you don't have to feel that because that's not real anyway. Then, if you're making music that you truly love and care about, you’re probably not doing something so original and left-field that nobody else will understand what you're trying to do. I just don't think that's going to happen.

So that means when you have an idea that you find really exciting, you can go all the way to the end of it without having to necessarily be worried about it living up to a certain standard other than the one that you are affirming for yourself. So, rather than being like, "you can do whatever you want" in thinking about it in a super nihilistic way, you have to do the Albert Camus thing and push past nihilism to get to the absurdist existentialism of it. It isn't a loss of values in a culture; it's a reaffirming of the values for myself.

I think that's exciting because then you can start taking from a bunch of different things and trying a bunch of other things. Rather than devaluing all of them in a postmodern sense, you're doing this metamodern reconciliation of "I want to write this string quartet in a super traditional way" because I've never done that. And I want to do that within my own kind of aesthetic with a more experimental take. These things can live together, and it's probably not going to be as radically weird as you think it is. It’s probably not going to be super alienating because if that concept is resonating with you and the thing that you’re interested in is resonating with you, then you’re affirming that value. You've reconciled these two points, even if it's just within yourself, within a concept or something.

But I don't think we need to be afraid of releasing that stuff into the world. If you're critically engaging with your creative practice and you find something that works—"I really like this"—there's probably going to be other people who really like it too.

Visit Kory Reeder at koryreeder.com and follow him on Bluesky, Instagram, Facebook, and SoundCloud. Purchase Homestead from Another Timbre or Bandcamp.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmChaz Underriner

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments