Isaac Sherman's work as a filmmaker, composer, and projectionist informs a distinctive sonic practice. Based in Los Angeles, Sherman combines analog and digital synthesizers, samplers, guitars, and vocals to construct music that brings together so much; to narrow it down, we hear experimental pop, kosmische, minimalism, ambient music, and experimental jazz. His filmmaking involves the direct manipulation of celluloid through frame dissection, lens manipulation, and hand-processing —a technique that reflects Sherman's ethos across all his creative pursuits. His art is handcrafted, opaque, and prone to happy accidents.

A Pasture, Its Limits is Sherman's debut album, a collection that draws on this hybridized palette. These songs are swirling collages of sound, existing simultaneously as tactile and ephemeral. Pop fragments are suspended like snapshots between granular textures and recursive loops. Themes of weather, longing, and personal transformation live within the material, evoking the diaristic intimacy of Arthur Russell and the poetic whimsy of Laurie Anderson. Instrumental passages unfold with meditative repetition echoing the melodic minimalism of Terry Riley, Laurie Spiegel, Maman Sani, and Hans-Joachim Roedelius.

The album's sessions span several years and two cities. A Pasture, Its Limits gathers recordings first sketched in Milwaukee and reworked after Sherman's relocation to Los Angeles. This temporal layering creates what Sherman describes as music written during "completely different" periods of listening and inspiration, "living in a different state and just in a very different time in my life." There's also a broader artistic philosophy at work: "Some of the best music is made with the simplest tools... that's when the humanness comes through music when you strip away all the glitz and the glamour of a million different instruments and just focus on one or two things."

Sherman embraces both influence and originality, acknowledging that "we're obviously inspired by what we listen to, whether we're actively listening to it or not." Influences from our pasts can't help but surface in our work. Sherman views this as an inevitable part of making art. His solution involves remaining "true to what feels good to us when we're writing music" while leaving "room for that which maybe doesn't exist yet, as far as you're aware."

In our conversation, Sherman discusses his thoughts on the act of creation, his relationship with both structure and improvisation, and how his background and experiences influence his musical output.

Michael Donaldson: How are you doing?

Isaac Sherman: I am doing good. I feel a little overwhelmed right now. I've been working on this box for all my synthesizers, and I’ve been using my little wood shop, sanding and working on woodworking projects all morning. But I jumped into this project and bit off more than I could chew with a certain deadline, and I'm just sanding my life away today.

Michael: So, a box for a synthesizer?

Isaac: Yeah. It's something to encase 90 percent of my music tools.

Michael: Are there companies that make things like that? You just wanted to make your own because there was a specific thing that was missing or lacking?

Isaac: Yeah, it was a size thing. It allowed me to fit the keyboard controller in there. Most modular Eurorack cases are specifically designed for Eurorack, but the one I’ve made is a hybrid. Everything fits, I don't have to plug or unplug lots of things, and it’s easy to travel with and organized. I want everything together so I don't have to think about it. But I also really love building, so I tend to jump into projects like this.

Michael: That's cool that you're into woodworking. It kind of makes sense—some of the song titles on the album reference nature, or just have almost agricultural terms. There’s "Ocean Park," "Tickle the Roots," and, obviously, "A Pasture, Its Limits." They're not woodworking-related, but they’re also not titles of someone who has their fingers on synthesizers 24/7.

Isaac: That's interesting. I haven't made that connection, but I do like wood and plants. I love being in nature. It helps a lot. So I guess that's a good balance.

The construction of Issac Sherman's wooden synth case.

Michael: Do you do a lot of things in nature in the LA area?

Isaac: I enjoy hiking. I walk around my neighborhood in Highland Park, northeast LA, as often as possible. There's a nice little hill by my house that is usually empty, like there are rarely people up there. And it's a nice place just to go up and escape. The vantage point is truly unique, offering a view of the neighborhood to the south and the mountains to the north, making it a lovely respite spot. I can walk to it from my house.

One thing I like about living in LA is that we're very much in a city, but we’re also pretty close to lots of preserves and state parks, which make it really easy to escape and forget that you live in such a metropolis.

Michael: So, when did you move there from Milwaukee?

Isaac: I moved to LA in late 2020. It was like the middle of the pandemic. I moved here with my partner at the time. She had family here and wanted to be closer to them during the pandemic. We moved in with her sister's family, so we weren't paying rent for a while. It was a relaxing and also awful time. I had visited LA many times and felt like I had a connection to the place, but I never lived here. After almost a year of being here, lockdown restrictions were lifted, and people started going out, shows began happening again, and film screenings resumed. It was fascinating to be here.

Michael: Let’s talk about the album, A Pasture, Its Limits. It's not often I listen to an album and I get so many impressions from it—like references, whether they're intended or not, music that fits within certain lineages. Often, when you listen to a record, there are usually one or two influences that you can pinpoint. But, for a record as cohesive as this, there are so many little reference points floating all through it. That makes it a lot more colorful to listen to than many other things. I wouldn’t say the album is retro or timeless, but rather outside of time. Does that make sense?

Isaac: It does. I'm surprised, shocked, and humbled to hear the word ‘cohesive’ because I worked on this record for several years, and between each song, there were probably like five to ten other tracks that didn't make it to the record. It spans a pretty wide gap of time in a fairly—I don't want to say drastic, but like a wide range of tastes developing. I try to listen to new music as much as possible, and I feel like my tastes are always evolving. Throughout writing this record, my listening habits changed frequently, and those influences found their way into whatever I was working on.

It makes sense that you picked up on there being many different times and styles within this. Honestly, it was a bit hard to put it all together because it didn't feel cohesive. It was like, "This song was written three years ago when I was listening to a completely different catalog of music and being inspired by different things, living in a different state, and just in a very different time in my life." But it was really interesting to put them all together and try to find a way to make them work together.

Michael: You said that your influences changed over time. Were they closely connected, or are we talking like complete one-eighties?

Isaac: I think there's like a coherent lineage that you could draw from what I was listening to a couple of years ago to now, but sometimes it was drastic. There were times when I was listening to lots of singer-songwriter stuff. And then in the past year or so, I've been listening to a lot more ambient experimental jazz music, clearly influenced by LA's ambient music scene. It's infectious. I guess I listen to a lot of instrumental music, and I prefer that because usually I like to go off and thought-drift and think my little thoughts. I can find words distracting.

Michael: Me too. I cannot work to music with words. I just can't do it.

Isaac: A lot of us can relate to that, and that's maybe partly why ambient music has had such a strong resurgence. That and everyone now has access to synthesizers, plugins, and digital audio workstations—anybody can make music. There's a vast collection of people creating minimalist ambient music solely to enhance a space. And I'm no different. I think I've been drawn more and more to music that has a lot of spaciousness to it, and I'm trying to do that more in what I'm writing now. I tried to add more space to this record because, by the time I had written all these songs, mixed them, and put them into their final form, I was craving a lot more space than what I had offered on this record. I was trying to fit it in while still honoring the nature of these songs, which can be quite maximalist, poppy, and full of many things happening all at once.

Michael: Did you set limitations or constraints for yourself when recording the album?

Isaac: Yeah. Honestly, this is something I'm trying to get better at because often I won't set constraints, and I'll just end up getting lost in a sea of different routes or avenues that I could take. I've come to appreciate and recognize the importance of setting constraints and parameters. But yeah, for me it's usually picking a few sounds and saying I can work with these. And I don't make music on a computer. Everything is hardware-based, which for me is mostly about not wanting to be on a computer. But I also struggle to stay focused. If I have a million options for sounds or for how to process something, I can really get lost in the sauce if I'm not careful.

Michael: Oh yeah, it's easy.

Isaac: Yeah. So I really appreciate having this little box that I'm working on with all of my synths. It's like I can work in this space, and that's like the first most basic step for me to set that parameter and work from there.

Michael: When I started making music, I just had a Tascam four-track, a guitar, a microphone, some cheap effects boxes, and a synthesizer. I'll go back and listen to some of the recordings that I made back then on this thing, and it's like, "Holy shit. I was so much more creative then.”

Isaac: Some of the best music is made with the simplest tools, and some of my favorite pieces of music that I've made are usually the pieces that were more playful, maybe just exploring one element of my setup, focusing on one synthesizer. I made a series of recordings with the Yamaha CS01 and a Casio, both through a delay pedal and a looper, and that was it. That was how I got into making music as a solo musician. I played in a rock band for many years on guitar, and then I got into synthesizers. And that allowed me to explore making music on my own, which was always loop-based and just simple. My favorite way to play music is to have a simple setup, focus on maybe one thing at a time. That's when the humanness comes through, when you strip away all the glitz and the glamour of a million different instruments and just focus on one or two things.

Michael: So, how did the songs on this album come together? Did they start simple? Because obviously some of them are quite developed.

Isaac: Everything starts somewhere, and usually, most of these songs, if not all of them, start from just jamming by myself and creating a synth sequence and then building on top of that. Sometimes I build up too much, and I have to pull it back and strip things away. Usually, it begins with just one sound. I think the second song on the record, "Upon Acre," started with a sample of my Juno synth, and it was just this one little sequence that I had going that I added things to.

I was listening to a lot of different artists using the Buchla synth, and I was trying to create as much randomness and chaos as I could in one line. I was doing that on the Elektron Digitakt with staccato, arpeggiated sounds, just building those on top of each other until I felt like I had a nice swirl of sounds. I wanted it to feel like something that was swirling around my head. But yeah, that just started with one sound.

Some of them would start with a drum part or a bass line. The song "Good Hug" began with a bass line that runs throughout the entire song, and it initially started as a brief sketch of a few different synth sounds I had in a sequence. I sat on that for years. And then I came back to it and added some words that I had written as a poem, reciting those on top of the music, and just built it up from there.

Michael: So it's also interesting that you talk about the instrumental music being important or prominent to you, but the striking thing on this album is the vocals.

Isaac: There's a lot of it.

Michael: Yeah. There's a lot more than I think people would expect, but it also adds to that whole flavor of out-of-timeness, I think, especially the way the vocals are effected throughout. How do you approach the vocals on this? Was that a natural thing for you to include in the album?

Isaac: Vocals for me have always been in a bit of a push-pull kind of relationship. I find that I resist adding vocals to my music as much as possible because I value music without vocals. And I like creating music that allows for space to think, not that music with vocals always impedes that. However, despite my attempts to avoid adding vocals, I always hear vocals as the next instrument. And sometimes I try to use my voice in a way that, if it weren’t my voice, it would be some other synthesizer or perhaps a wind instrument—something that has more of an organic, human feel to it that's coming out of us.

The way that I approach vocals is probably a little different for each song. Going back to "Upon Acre" again—it was all synthesizers and that's all I really set out to explore. But I record whenever I'm building something up or improvising on my own, so I have a record of it. I’ll go back and listen, and if there's something that I like, I will pull that out and work on it. The vocals for "Upon Acre" happened because I was just singing gibberish over this synth part, and I had this vocal processor, and I liked the sound that I was getting. More than anything, I was trying to create another lead instrument sound. I wasn’t really singing words, just making consonants and vowel sounds that I felt added to this sea of synthesizers. And that initial vocal take is what made it onto the record. Later, I transcribed the words I thought I was saying and tried to decipher and come up with words from that. And the result is the lyrics that I've decided are what that song is, even though I'm not actually saying those words intentionally, though now, when I play it live, I am.

Michael: Brian Eno, on his vocal albums, would enunciate vowels and nonsense words in his initial vocal takes. But he would then make words out of the vowels that seemed to fit the songs, and then rerecord his take with these words. So I think it's funny that you almost adopted the same method, but you kept the vowels and the enunciations there without the words. The imagined words came after the recorded song. That’s neat.

Isaac: I think most of the time that I am creating vocals for a song, it's usually the same. It's just with my voice over something, probably recording it, going back and listening and picking out melodies that I like, then adopting words and lyrics to that line, trying to fit it in. But sometimes I find that it doesn’t capture that feeling of the original moment. In the case of "Upon Acre," I wanted to preserve that feeling. But yeah, with other songs, these melodies and vocal sounds are born out of the spur of the moment, which I feel like is probably not all that unique. A lot of people do that when they're scatting over the music. When I played in the band that I was in for most of my life, my fellow bandmates and I would come up with vocals by doing that. Sometimes we would make words to fit that melody, and sometimes it would just be, "Let's leave it to just be whatever sounds come out because it's an instrument." It's an instrument, and just because it's coming out of your mouth doesn't mean it has to be a word necessarily.

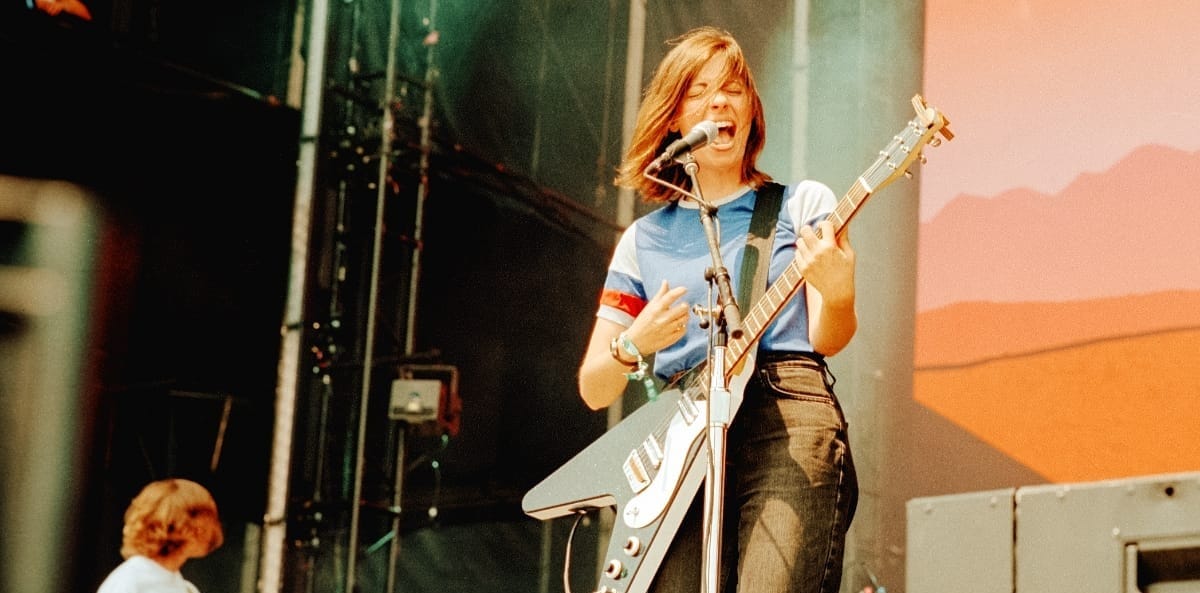

Michael: How much of a role does improvisation play in what you're doing with this record?

Isaac: It's the central role. Everything I write, regardless of how structured it eventually becomes, starts off as an improvisation. This record retains some elements of improvisation, but it’s very structured, a composed collection of songs that have beginnings, middles, and even choruses. But yeah, it all starts as improv. I usually am laying down lines—again, what I do with vocals. If I'm just singing something and I record that take and I like it, I go back and kind of mess with it and maybe transpose or reorder the notes. Eventually, it gets structured, sometimes a little too much for me.

I've been trying to allow more room for what is clearly improvisation and not over-structure things as much because I really like there to be a fluidity. I prefer not to be locked into a BPM, although it’s challenging when I rely on several instruments that need to be sequenced together. I try to leave lots of room for improvising on top of otherwise structured sequences. And to me, that's the most fun part about music is just being playful and playing what feels natural in that moment.

Michael: What happens to these songs live? Do the songs on the album become more improvisational?

Isaac: Sometimes. I'm trying to leave room for improvising on some of them. Some are pretty structured when I play them. Some of them are difficult to play live, so I rely on the sequencing element of all the devices I'm using. For the most part, they'll be predetermined and structured. But I try to leave some room to improvise on top, whether it's vocals or a lead synth line. As much as I love playing shows, playing songs the same way over and over again really sucks the life out of it for me, and I find myself practicing it to death. The way for me to revive that is to leave room for openness. Sometimes a song will be a song, and I'll play it as close to the original version as possible, but as long as the piece that follows is improvised, then I feel like I'm honoring my innermost desire to create music on the spot.

Michael: I appreciate that because it's almost like you're squeezing more out of the song rather than just leaving it in its state. The song's also kind of evolving with you.

Isaac: Especially after moving to LA and becoming entranced with the experimental improv jazz world that's here. It’s so rich.

Michael: Yeah. The jazz scene in LA right now is fascinating.

Isaac: It's incredible. I'm so lucky to be around it and have access to that. You can see many musicians who might not be traditionally described as jazz musicians, but they share a mentality of approaching music as a unique moment that requires us to be aware of the time, space, and the sounds we're making. It's a jazz improv mentality applied to so many different genres and sounds. That has so inspired me, and I’m trying to lean more into my own desires to improvise. I've always loved to improvise, but I haven't always felt comfortable allowing myself to do so in a performance. I always felt pressure to have most of my performances be pretty structured and mostly premeditated. Lately, I've been adding more space to improvise and allow for randomness, and simply being present in the space.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmMichael Donaldson

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

Comments