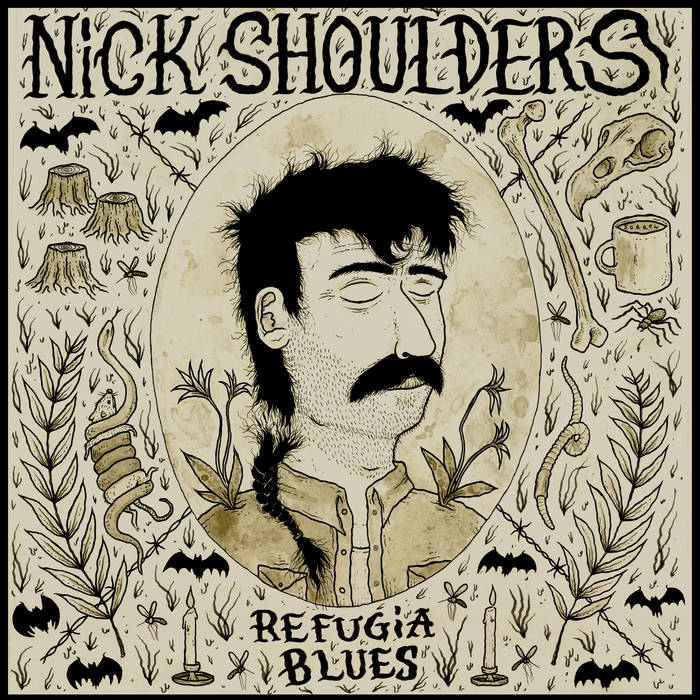

The orchestration of Nick Shoulders' fifth record, Refugia Blues, may be solemn and stripped back, but his message and approach are far from it. The newest offering from the Fayetteville-based singer-songwriter embraces the traditional sounds of his familial roots in the Deep South and Appalachia. He attributes much of his sensibility to the influence of a rural way of life, from his early days developing singing skills by imitating birdcalls to growing to appreciate his ancestral ties to Ozark music. "Being part of this tradition isn't meant to be regressive; it's meant to be liberating," he said in a press release. He loves where he comes from and is proud to tell you so: it's ever-apparent in conversation. At one point, as we spoke, Nick's attention was interrupted by a group of passersby unexpectedly drifting down the creek behind his Arkansas home.

The inspired solo performances on Refugia Blues pull their weight in bringing Shoulders' potent songwriting to the forefront. He wrote, produced, and performed every instrument on the record. "Kind of flawed, often flailing, always trying," he repeats on the toe-tapping, self-aware second track "Bored Fightin." The following song, "Hill Folk," borrows melodically from the traditional country number "Cowpoke." He rallies against the false narratives of working-class southern people and the commodification of country music. Vulnerability is masterfully balanced with intensity in many of Refugia Blues' finer moments.

The duty of weighing a reverence of the past with the reality of the present is not lost on Shoulders. He describes the album as "a Trojan Horse that can be accepted by people who don't hear anything to challenge their sense of comfort and superiority" in a fundamentally imbalanced world.

I spoke with Nick Shoulders about the history of Southern resistance music, his early DIY days in the unique Arkansas music scene, and his journey from a hardcore kid to embracing the traditional music that is in his blood and bones. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Sam Bradley: At what point did you start writing your own songs?

Nick Shoulders: That would have been in 2016 or so. I had a weird split personality before that, where I played string band music and yodeled in the woods as a kid and had all that podunk stuff that was just part of the things I did: playing square dances, busking, and whatnot. I was also in hardcore bands and metal bands. I was writing songs for both of those personalities or versions of music that I participated in, but it was never under my actual name. It never really felt like it was a true representation of what I was, which was somewhere in between those two extremes. So yeah, I wasn't really writing my own songs because I was a teenage drummer. That came later, like in my late 20s.

Sam: Are you still based in the Fayetteville area?

Nick: I'm standing in Fayetteville as we speak. I'm a bit too stubborn to live anywhere else. I've tried, and I'm just not very good at it.

Sam: What can you tell me about the music scene in Arkansas?

Nick: Maybe it's not as unique at first glance, but once you're here, it starts to click. I think we have to be uniquely creative and defiant to make a scene work, because there wasn't even an interstate highway through Northwest Arkansas until 2000. Since I graduated from high school in 2008, this town's about doubled. It's one of the very few small, hip, and growing metros in the United States that has skyrocketed in population, but our creative class has not grown proportionally.

The Walton-backed culture machine of Northwest Arkansas has done everything possible to crush a DIY scene and to force us to interact with their sanctioned venues. There is no mid-sized rock and roll bar that can host a touring band in this city anymore. That just doesn't exist, and so all music is within these Walton-sanctioned spaces, and those events are often poorly attended. Backyard shows are still way more fun and better attended than anything the Walmart apparatus puts on. It's remarkable how hard we have to fight to have anything resembling a scene here.

But on the other side of things, string band music and Arkansas old-time, fiddle and banjo stuff, is endemic to this place, and it's part of the cultural makeup. You can still visit a sorghum pressing site where people harvest cane and press it with mules into molasses, accompanied by the sound of string band music that was first recorded in the 1920s. You're not hearing a theatrical, dramatic reinterpretation. It's actual people who are descended from the same folks who have always been doing it.

We're still battling random city planning decisions where, say, the place where the square dances are hosted suddenly gets its lease terminated. So, it's not perfect. I do see the long-standing continuity of Ozark old-time music having far more of a chance of surviving this in a lot of ways than punk shows in the basement, which is not usually how it goes.

Sam: Do you feel any weight or personal responsibility to help usher in new things there and help the scene in Fayetteville?

Nick: To an extent, I definitely recognize the little teenage me who was drinking on backroads and practicing with metal bands in barns. I want it to be better for the kids. I have been to a couple of heavy shows at a VFW here, and I'm like, "Man, the kids are all right." They are fighting so hard to keep this music, this anger, and this righteous indignation alive. But truth be told, I think what has really kept me here is the cultural continuity with the old-time music and the long-standing traditional music forms in the area.

I can drive a half hour and be in millions of acres of contiguous forest. I can drive 5 minutes from my house and be in clear, cold creek water. Our access to physical common areas, commonly held forest and river systems, translates to having a rich musical commons. Things like fiddle tunes and old ballads predate the commodification of what we now call country music.

Sam: How do you try to continue the 'good' of country music while balancing long-standing traditions?

Nick: I think that my luck in having access to intact green spaces and that desire to protect that mode of existence is there; it's a part of me. For a long time, I rejected traditional music forms because all I had was the commodified radio country of the early 2000s as a reference point. I was embarrassed by the way my grandparents sang. I was embarrassed by some of the skills I had built in the woods, like bird calls and yodels and all that stuff. I thought the avenue for protest was punk and metal music, so in those bands I was yelling what I'm now yodeling.

It took me a long time to understand my own cultural origins and realize that an innate sense of protest and resistance was within me, in my bloodline, and in this place, physically in the trees and the soil. I think many people from this area in the South can research what was hidden from them, tracing their lineage back to resistance movements and rural self-determination. It takes a certain amount of digging to realize what was purposely obscured for the sake of making us easier to control.

There were obviously a lot of problematic or damaging songs in the early days of what was called the hillbilly canon, before it was called country music. But there were also tons of songs of resistance and connection to the land. Taking a basic example from one of the founding people of country music, Sarah Carter recorded "Single Girl Married Girl" in the '20s. It was a bold feminist anthem that turned a lot of the gender stereotypes of that age on their head. The idea that country music has always had this regressive streak or this antagonistically conservative core to it, I fundamentally reject it. I don’t think you see that enter country music until the Civil Rights Movement.

Once it started becoming about cowboys and ranches and not based in the South, you suddenly get all the white supremacist political affiliations that come with that. I think people miss that the reconfiguration of country music was profit-oriented. It was a small percentage of the US as a whole that was scaled up and taken advantage of.

When I started writing these songs, it wasn't so much like, "Oh, I'm going to make leftist country music." I wanted to accurately represent what I love about this music, which is where it came from. When I say that, I mean the cultural, geographic, and demographic crossover that created early country music. A lot of that is inherently pro-working class and more or less anti-ruling class.

When I wrote a lot of the songs on Okay Crawdad, I didn't have a PR engine, and I never sold out a show. I was playing for tips in moldy bars. So there was no grand scheme of what was going to put me on the map. It was more like, "No, I want to sing like my grandparents sang. I want to represent the cultural and geographic experience I'm actually from." I think a byproduct of that inevitably was these threads of resistance. I think that it has far more to do with the fact that this musical family, this musical lineage, has far more resistance baked into it than it does regression. That takes research, and it takes time to figure out, but there was no conscious decision of "I want to stick out of the country crowd by being an outspoken leftist." I want to stick out from the country crowd by not being a poser.

Sam: It's unfortunate that no corner of anything is safe from profit or self-interest, regardless of messaging or slant. It seems like it should just be about being authentic and honoring things that you have respect for.

Nick: Profit-oriented is like a version of self-centered. However, I do want to push back on that too, but in a very gentle and respectful way, because people use the word 'authentic' in connection to country music constantly, which I think gets sticky when you start thinking about who has access to being considered rural. It's usually people who have had the lottery of luck of being born into some sort of circumstance, and they had access to land.

I think authenticity is fine and cool; we should be concerned with people representing themselves accurately. I'm far more interested in continuity. I grew up on a dead-end road surrounded by forest, and I learned to call along with owls, but I also grew up watching Nickelodeon and eating frozen chicken nuggets, like everybody else. The idea that I represent some kind of special fossil of Americana, I think it's stupid. I think it mires us in this really pointless conversation about authenticity. But if we make this more about continuity and continuing aspects of traditional music that predate the genre and predate the commercial product that country music became, then we're talking about something far more vital and far more unique to the person bringing it.

My particular continuity backwards is to Southern Gospel singing traditions, and I just happen to be lucky enough to have my grandpa's fiddle. Both sides of my family sang and played music that would have been considered part of the roots of country music, but never participated in the commercial product that country became.

What I would rather see is like if you're a theater kid from Wichita, Kansas, and you have German ancestry, I would much rather hear you play polkas than hear you fake Ozark string music. I think that is where I hope this idea of continuity takes root, because I think people's actual cultural origins are far more interesting than putting on a cowboy hat and faking a twang.

Sam: Did stripping the sound back create any challenges for you after coming off a record with a more raucous energy?

Nick: Potentially. My first instrument was the drums, and when I started playing traditional music, I was drawn to the older stuff because it has a much harder backbeat. It was all meant to be danced to. A lot of what you hear in my version of country music isn't throwing back to some bygone era just for the sake of doing it. It's like that because the music was mostly played for dance audiences in New Orleans and Arkansas.

I have a heavy rhythmic background in the way I play guitar. I can't play a barre chord. There's no money past the fifth fret. Everything I play is super 'boom-chuck,' super rhythmic. I did find that once it was just me and a guitar, I was expecting it to be a lot more difficult, and I’d think, "Oh man, I'm going to have to fill out all the space. It's not going to feel totally right." Having that rhythmic background made it sound full, even despite lacking other instruments or the classic tropes of a well-rounded, furnished record. I was actually really satisfied with how things went. There were a couple of moments where my buddy Eric, who runs Homestead Recording here in Fayetteville, was linking up two parts of a song, and the timing didn't shift. He's like, "Hey man, I just want you to know not a lot of people can do that. You're just playing by yourself, and the timing is rock solid."

Sam: I'm a big bluegrass guy. There's a similar inner metronome thing. It becomes almost like riding a bike.

Nick: Yeah, you get it then. It's like it just starts to be in your bones at that point.

Sam: Is the tour for this record just you by yourself, or are you with a band?

Nick: I'm on and off with the band. I was doing one-man-band stuff for a stretch this summer. We've already been playing "Dixie Be Damned" as a full band song for the better part of a year. The opportunity to retranslate something that was recorded as a solo performance and rehash it is super fun. That being said, with this record, I wasn't really interested in participating in the average release cycle shenanigans. For example, we didn't have music videos; instead, we recorded me playing the whole record live at Gar Hole Studios. It held no appeal for me to take this stripped-back solo acoustic song and make a real-ass music video for it. The live cuts felt like a much more accurate representation of what these songs sound like.

I feel that, in many ways, the release circuit in the modern music industry is done with this infinite growth delusion. There is this capitalist paradigm that everything is supposed to expand and increase. Part of that is every single release, every single song, every album is meant to garner a new audience and draw in new people. Frankly, with this record, I'm not interested in expanding the variety or number of people who interact with these songs infinitely. I want to make something that I care about for people who already care about these songs. So it's definitely a record made for folks who already give a shit.

Frankly, there was so much that was unenjoyable about pandemic times, but not having to interact with the touring music apparatus and its moneymaking engine was sort of a plus. I still feel guilty every night knowing that someone in the audience is struggling to make rent, but they gave 25 bucks or whatever for that show and maybe even bought merch or drinks. I just know people are struggling and that it is a difficult time to be throwing discretionary dollars towards entertainment. It meant a lot to me, being a 14-year-old, and being able to listen to live records from any band I respected, so I think giving the fulfillment of that on YouTube is the least I can do.

Sam: What is your relationship with touring like generally?

Nick: I feel like all my best travel years happened in an unsanctioned space. I was busking on street corners, living out of my van, playing for tips in little bars. Without sentimentalizing or glorifying what was often hard and involved a lot of struggle, what I traded for prosperity was autonomy. That was really important to me as someone who is fiercely independent and struggles with authority. That style of mobility and connection to my creative outlets was important.

So I'd say I've got a pretty tortured relationship with touring, as I think anyone sane ought to. I feel that if you value your labor, your time, and your sense of self, including your physical, emotional, and mental health, you should be really skeptical of touring. If none of those things compute for you, then you will be easy to take advantage of and exploit.

I have pretty rigid labor standards. I won't tour more than a few days in a row. I won't drive more than four hours before I play. I try not to play more than X amount of shows a year. That has cost me on a lot of fronts. I don't take on debt. I know who I am. I know what my tolerances are. I know what I prefer to do with my time. To sit in a van and earn other people money and contribute to this touring machine that I neither respect nor want to continue—it's just not for me.

Sam: I can imagine people who are young, impressionable, and excited just to play are often taken advantage of in that setting.

Nick: Yeah, and you make a good point about it being age-specific. I think I'm lucky that by the time music started working for me, my body was half used up. Touring hinges on having an able body that is available for profound exploitation and burning up a human being. Like I said, my body is already half burned up, so the same incentives don't work on me.

Sam: I know the sessions for this record took place in January of 2024. As you take stock of yourself, your life today, the world in general, is there anything that you wish you had added or done differently on Refugia Blues? Is there any thought of, "Oh, I wish I had added this song or this line," or is that sort of next album's problem?

Nick: I think there are two parts to my answer. Firstly, I don't write songs the way that people interact with clickbait or with social media. I know a few songwriters who can turn around a song based on every event that happens in a news cycle. That's remarkable, but it's not how I operate; it's not how I want my craft to live. I'm not writing diary entries about the spiral and collapse of the American Empire. I want a lot of these songs to be universally approachable and have a resonance that outlasts the event. A lot of these songs I want to have the same staying power and same impact if somebody were listening to them during the Reconstruction era, or if they're listening to them during the Red Scare, or if they're listening to them during the post–Civil Rights movement era, or if they're listening to them now. I want these themes to be bigger than the individual events that create them.

I had verses in "Dixie Be Damned" that I cut because I thought the song was just too long. In retrospect, I'm like, "You know what, that would have really hit a nerve with a lot of people who are faced with this incredibly difficult circumstance that we're in right now." I wouldn't call it regret so much as lessons for next time.

If there's a Mount Rushmore of country music, I don't want to be a face on it. I want to be just another rock making up the body of that hill. I feel like every one of these records is just another piece of a thing that's way bigger than me, that I'm just grateful to be part of. I want this to speak to people who remember what country music, or traditional music, sounded like before it was so mercilessly commodified. I'm kind of trying to write music from the past, not because I want to live in the past, but because the future I hope to be part of incorporates and honors the ways that things lasted and functioned for countless generations before, well before anyone ever bought a record, you know?

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmSam Bradley

The TonearmSam Bradley

Comments