1970 was on its way out, and Nixon was two years into his first term, when rock critic Greil Marcus, a founding staffer at Rolling Stone and contributor to many other publications, got called in to watch a debate on The Dick Cavett Show—a debate on art, history, and what really matters, between critic John Simon; actress/singer/dancer Rita Moreno; Yale professor turned best-selling author Erich Segal; and rock and roll's force-gale wind, Little Richard. Marcus had thought of archetypes and myth in rock and roll for about five years at that point (see below), but Little Richard ripped shit up, demanding supplication and even worship, as the only one on that stage who broke the world to demand a new one; the only one whose name will live with true history.

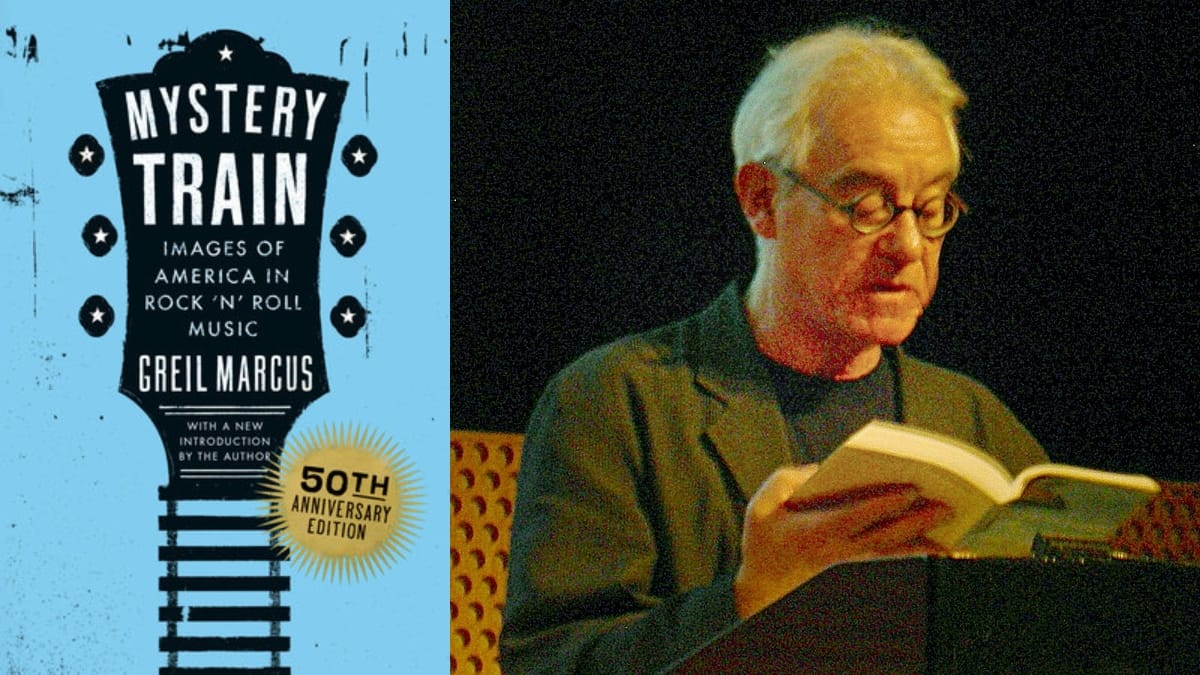

Marcus' book Mystery Train, first published in 1975, revised several times, and now revised one last time for its 50th anniversary, begins (past a few introduction notes, testimonials, and a two-page comic), with Little Richard blowing everyone else away and ends, with the last pages of its shifting "Notes and Discographies" section, with Jerry Lee Lewis debating religion, truth, and obscenity with his nominal boss, Sun Records' Sam Phillips—two more people who broke the world. "Sam's crazy," said Lewis to an interviewer. "It took all of us to screw up the world. We've done it."

But what of all the worlds in between?

Marcus set out to investigate America in terms of the music, but also the resonances behind and between the artists. He started with two "Ancestors": Jack-in-the-box-of-all-trades Harmonica Frank Floyd, the mythical wanderer pasted with clown makeup "who's seen it all, remembers about half of that, and makes the rest up"; and bluesman Robert Johnson, who can travel but can never escape, a netherworld of demons, ghosts, and the Devil, to whom he just may owe his own soul.

A quartet of "Inheritors" follow: The Band, four Ontario musos plus an Arkansas drummer, plumbing the depths of American pleasure, community, fear, shame, and transcendence; Sly Stone pegged to the myth of Stagger Lee, that homicidal Superfly slick dick aiming his pistol through demon eyes; Randy Newman, lord of the unreliable narrator, populating our nation with lovers, failures, dreamers, losers, and the odd psychopath; and finally Elvis, a sweaty heaven-blessed Samson who almost, but not quite, closes the chasms in American society (new vs. old, open vs. closed, sanctified vs. condemned).

The front of the book hardly changes at all; the "Notes and Discographies" at the end change with each new edition, documenting vinyl, CDs, and sometimes other releases, plus debates, arguments, successes, failures, and mysteries, since 1975. Greil Marcus courteously took some questions over email, looking back and coming in for a landing.

Andrew Hamlin: The book kicks off with a debate on The Dick Cavett Show—did you watch Cavett often, or did he just happen to be on? What were your prior impressions of Cavett himself, Rita Moreno, John Simon, Erich Segal, and Little Richard?

Greil Marcus: We lived in a house where every room was open to every other. I was in the living room working on my Ph.D. orals submissions, while my wife and mother-in-law were in the bedroom watching Cavett, which we usually watched all the time. It was noisy, and they kept saying, “You've got to see this.” I kept going in and out and finally stayed, agog.

Friends late of Rolling Stone were trying to start a new magazine and were asking for contributions for a dummy issue to raise money. I spent at least a week reconstructing the Cavett episodes for them. They used it, but the clear story was a rare interview with Groucho Marx that made national news because he said, among other things, that the only hope for America was for someone to assassinate Richard Nixon.

Despite that, the magazine never happened. I later used the material as the opening for my first piece for Creem, a long state of the (rock 'n' roll) nation piece called "Rock-a-Hula, Clarified"—and then for the start of Mystery Train.

My editor said whatever else I wrote, people would stay with the book to see if there was anything else as good. Since then, with the availability of old TV shows, my reconstruction, as I've always thought of it, is not completely accurate. Or all fucked up.

I confess I've never done the simple thing and watched the actual show. I don't care. I had a great time writing it. Probably had a lot to do with why, though I barely passed my orals, I ultimately left grad school and struck out on my own.

Andrew Hamlin: The book obviously traces back to your famous "What is this shit?" review of Dylan's Self-Portrait, 1970. How, and for how long, had those ideas percolated for you? When did you begin to think in terms of archetypes and myths?

Greil Marcus: In the American Studies seminar in 1964–65 that I wrote about in [the book] What Nails It.

Andrew Hamlin: You started the book as Nixon squashed McGovern; you finished as he flew off in the chopper. How did his throne-to-thud arc play against your writing?

Greil Marcus: I think that's all in the book. Or should be. In the sense of high stakes in, say, how the guitar solo at the end of the Band's "King Harvest (Has Surely Come)" turns out.

Andrew Hamlin: You've always praised your editor Bill Whitehead (named on the dedication page of some editions, though not this one) for his crucial role. How did he work with you to define and shape the book?

Greil Marcus: By being a flinty and critical reader, and as committed to the book as I was, if not more so.

Andrew Hamlin: Your working title was "Phonograph Blues" [from the Robert Johnson song]. Why did you change it, and how did you settle on Mystery Train?

Greil Marcus: It was better. No one would be talking about this book now if it had been called Phonograph Blues. Though I'd still like to do a collection with that title.

Andrew Hamlin: If I remember right, you started listening to Robert Johnson in the wake of Altamont [the 1969 festival], the worst day of your life to that point. What do you think you would have done if you hadn't found Robert Johnson?

Greil Marcus: Not this book. Lived a poorer life. Not thought below the surface. Not played "Stones in My Passway" all day long. More than once.

Andrew Hamlin: How did you acquire [Sly and the Family Stone's] There's a Riot Goin' On, and what did you think as you spun it the first time?

Greil Marcus: I bought it at the store and thought, "Every word I've read about this is a lie."

Andrew Hamlin: Had you thought much about Stagger Lee before Riot, or did the album kickstart it?

Greil Marcus: Stagger Lee was always there.

Andrew Hamlin: You refer to George Jackson's prison memoir Soledad Brother as discredited, but also call it a crucial influence for your thinking about Sly Stone and Stagger Lee. How did the book rise and fall? How did it figure alongside the rise and fall of the Black Panthers?

Greil Marcus: Jo Durden-Smith's book Who Killed George Jackson? ripped the skin off the story. I never saw left politics the same after reading him. It was very close to home. He left not a piety or an illusion whole. And he wrote like Ross Macdonald.

Andrew Hamlin: Randy Newman always sings in his characters' voices, you wrote, "except when they are women, but he will manage that someday." Did he ever, and if so, where?

Greil Marcus: I don't think so.

Andrew Hamlin: Your work isn't predicated on knowing musicians, but I confess curiosity. What was Harmonica Frank like, and how did you get to meet him? Did you ever get to watch his act?

Greil Marcus: I never met Harmonica Frank. I don't remember who put me in touch with him—it might have been Greg Shaw of Mojo Navigator and Who Put the Bomp!, who passed me tapes of Frank's records well before there were any reissues, or it might have been Steve LaVere, who despite his seizure of the Robert Johnson estate was always forthcoming with me—but Frank and I talked on the phone, and he sent me any number of eloquent handwritten letters.

Andrew Hamlin: How did the five men in the Band compare and contrast in terms of attitude, aesthetics, and surprises?

Greil Marcus: I did know them. Richard [Manuel] was always sweet, even when bereft. Rick [Danko] was warm. Garth [Hudson] taciturn and generous. Levon [Helm] full of enthusiasm, vehemence, and heart. Robbie [Robertson] and I were friends, in touch in various ways from about 1970 till a few years before he died.

Andrew Hamlin: Randy Newman once quipped that it was hard to work with your face figuratively looking down on him. How has your acquaintance with him gone along?

Greil Marcus: We met for an afternoon up in the Wine Country in 2003. All of that conversation is threaded through the Notes. Other than that, we've never been in touch. He was a nice guy. Subdued. Serious. Open.

Andrew Hamlin: Going through your Elvis "Presliad" again, I'm struck by how Elvis ultimately fails to resolve American contradictions: This banana ever peeled, the zipper pulled. But the ways in which he comes so close and the ways he ultimately fails remain fascinating. Have your fundamental thoughts on Elvis changed at all over 50 years?

Greil Marcus: He's never ceased to fascinate me, or to leave me less than dumbfounded by the depth and singularity of his singing. Of recent literature, I think Preston Lauterbach's Before Elvis, about the Memphis culture that shaped Elvis and from which he drew, has added the most to the story. When Dylan released "Murder Most Foul" and began playing his hydrogen jukebox, calling out for "Mystery Train," it was back on the air, and still sounds like a miracle to me.

Andrew Hamlin: I see plenty of Raymond Chandler in the book, but couldn't find any Dashiell Hammett. Any thoughts about C vs. H?

Greil Marcus: Chandler touches me in a way Hammett doesn't. Always has. I just re-read The Lady in the Lake last week. I love the way he writes, the naturalness of it, the hard stops in the sentences.

Hammett was a completely different kind of man and a completely different writer. The idea that his own government sent this great patriot to prison breaks me whenever I think about it.

Andrew Hamlin: The Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams Sr. discourses caught my eye. Jerry Lee Lewis famously dubbed himself one of only four true singing stylists in history—anointing Rodgers and Williams along with Al Jolson. Your thoughts?

Greil Marcus: I think you have to bring in just a few more. Sinatra. Holiday. Charles. Dylan. You know?

Andrew Hamlin: If I read you right, Charlie Rich left you feeling sympathy for Nixon. Could anything make you feel sympathy for Nixon?

Greil Marcus: Well, he did. For about a minute. But it was a real minute.

Andrew Hamlin: How does Nixon compare and contrast with Trump?

Greil Marcus: People never loved Nixon. People never wanted to be Nixon. Nixon was a sleazy little operator. Trump is a mafia don who, in his own mind and in that of millions, is the rightful king of the world. It's a natural law that every Republican president will make the previous one look good. Trump has run the table.

Andrew Hamlin: Trump recently got a medal from the Richard Nixon Foundation. Do you feel time's circle, or perhaps a manacle, closing?

Greil Marcus: They must have thought it would make them look good. Trump probably threw it away.

Andrew Hamlin: You've lost many folks over 50 years, and this will quite likely be the book's last update. Anything and/or anybody you ended up leaving out this time around, and if so, any regrets?

Greil Marcus: I tried and tried to get an early edition of Robbie Robertson's just-published [memoir] Insomnia for this edition. It was promised over and over, but it didn't happen.

I started a file for the fantasy next edition the day this one appeared in my hands—not two weeks after I'd made the last changes, marking the deaths of Annye C. Anderson, Robert Johnson's stepsister, and Brian Wilson. And Robbie's book is fascinating. He was the most self-aggrandizing person on the planet, and he can make you believe him when he talks.

Andrew Hamlin: And I always feel obliged to ask—what are you listening to now, and how do you feel from it?

Greil Marcus: The new Bob Dylan movie bootleg set Through the Open Window. Constant Bryan Ferry for the Listening To book I'm writing about this music.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments