Sean Imboden discovered the creative drain of being a professional musician during his eight-year tenure as a touring saxophonist for Broadway productions, including the Tony Award-winning brass ensemble Blast! II. Despite appearances on The Tonight Show, recordings with Grammy-winning artists, and a steady income, something was still missing. "After a while, I would kind of dread those 7:00 PM downbeats for the Broadway shows," Imboden recalls. "Even though it was a steady gig and I had everything to be thankful for, I had to sort of look inside and say, 'Okay, what really makes me happy about this music? And can I find a way to live a life where I'm pursuing that?'"

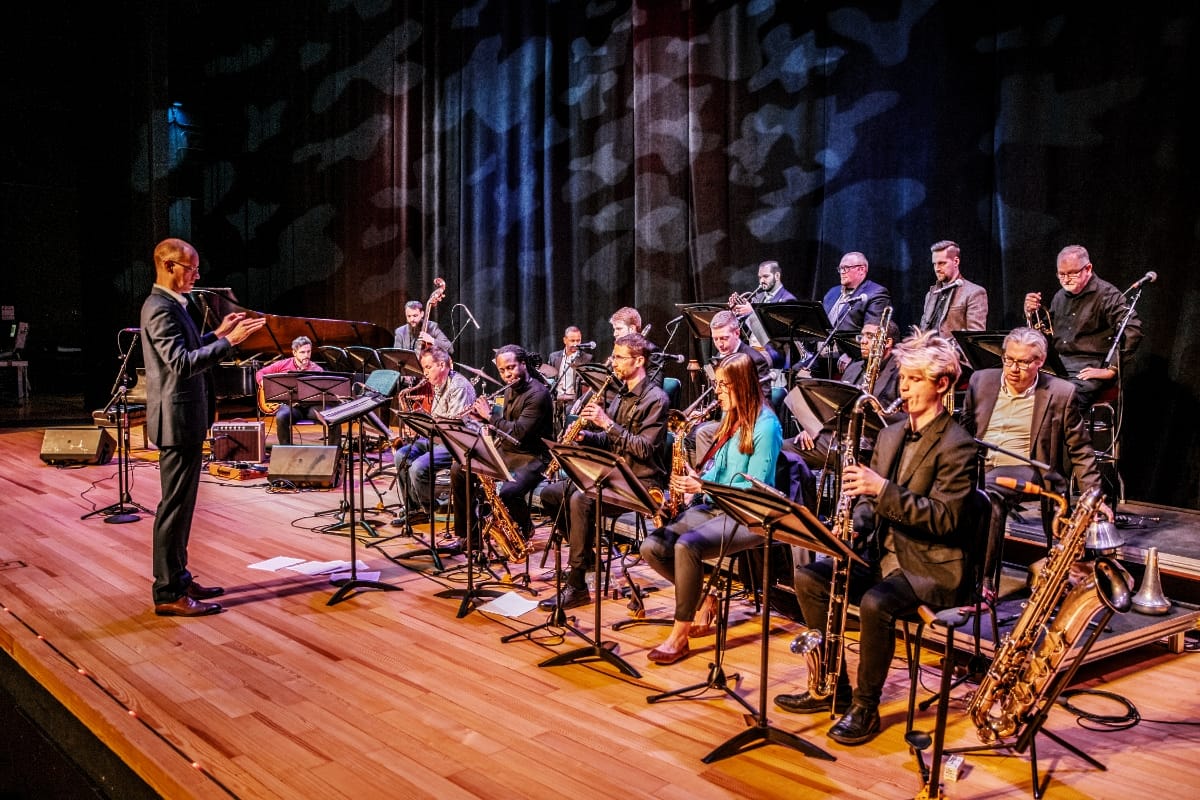

The answer came in 2017 with the formation of the Sean Imboden Large Ensemble, a seventeen-piece modern jazz orchestra that has become a fixture on the Indianapolis new music scene. His latest album, Communal Heart, also captures both the musical and social philosophy that drives his work. The album title reflects his belief that great music demands a genuine connection between musicians, audiences, and the material itself. In turn, the project was funded through a successful Kickstarter campaign, evidence of the devoted community that has coalesced around Imboden's spirited compositions and the ensemble's fiery performances.

Growing up in a musical household prepared Imboden for the realities of professional performance. His father was a woodwind player who played on recording sessions and Broadway shows, while his mother was a freelance violinist. “I remember the middle of dinner, phone rings,” Imboden remembers. “My father’s jumping up, picking up the phone, 'Hello!’ It might be his next paycheck for a gig." This taught Imboden the hustle of musical life, but he grew to realize that artistic fulfillment and financial stability need not be mutually exclusive.

Communal Heart showcases compositions that pulse with autobiographical energy, from the powerhouse opener "Fire Spirit,” which Imboden describes as embodying "a drive so strong it becomes impossible to ignore,” to the forward-looking "Portal Passage," a piece about seeking transformation through creative risk. The album features his core ensemble of Indianapolis-area musicians, including trumpeter John Raymond, guitarist Joel Tucker, and pianist Chris Pitts, alongside veteran mentors Steve Allee and Rich Dole, who served as producers.

Sean Imboden was a recent guest on the Spotlight On podcast. In his conversation with host Lawrence Peryer, he discussed his compositional process, the logistics of leading a large ensemble, and how he has built a sustainable model for creative music outside the traditional industry framework.

You can listen to the entire conversation in the Spotlight On player below. The transcript has been edited for length, flow, and clarity.

Lawrence Peryer: How does a large ensemble differ for you as a leader when putting together a recording project like this?

Sean Imboden: I think one of the tricky things is just trying to zoom out and have a bird's eye view of what we're doing. Because sometimes it's easy to get in my head and be like, "Well, it's all about this song, or it's all about this melody, or we gotta get this groove or feel right, or I have to make sure I'm telling everybody how to play everything exactly right and I need to control everything."

But I think in a lot of ways it's better to say, "Okay, I'm dealing with a group of highly trained, highly creative individuals, and I need just to allow them as much as I can to do their thing." Now, that being said, with a big band, I have to write actual parts for everybody so that it's not total chaos or cacophony when we're performing. So I’ve got to be pretty exact when it comes to "this is the time you play this part, you play this part." But then, remembering that if I sort of give them freedom and let the sparks fly when we're playing live, or maybe even sometimes in the studio, then that can be even way better than something that I can concoct or compose in my head.

When you're writing for seventeen people, you have to sort of say, "Okay, the trombones are doing this now, this is their role. They're doing a background thing. Now they're in the melody role. Now it's all about the drums." You're sort of shaping this form that you want each piece to take, but then leaving those spots open for just circumstance or cool opportunities that you might not think about when you're composing.

Additionally, there are logistical aspects to being a good leader. I want them to have the best opportunity to do well, and that means getting the parts to them early, ensuring the parts are done well, and then getting their feedback on the rehearsal. You know, the hardest one for me is trombones, and I'm always asking the trombones like, "How, on a scale of one to ten, how difficult is this four measures for you guys to play?" Because I want them to enjoy it too.

Lawrence: What is it about the trombone that is particularly challenging for you to compose for?

Sean: As a woodwind player, I'm pretty solid on the saxophones. There are flutes, soprano clarinet, alto, tenor, baritone, and bass clarinet; I play all those instruments, so I'm comfortable there. With the rhythm section, I've always played in bands that have had rhythm sections, so I would always get that in my head. I sort of knew what I wanted, and then in rehearsal, I can hear it and say, "Maybe move to the right, or just hang out on the hi-hat for now."

But trombone—you know, they're in bass clef, which is secondary clef. Saxophones are in treble clef. So when it just comes to purely notating that, I'm not as comfortable reading and then notating the bass clef. Then also when you're maneuvering around on the trombone, different positions can hit certain partials and overtones and harmonics. And all that stuff, I don't really know. I've never played a trombone, but I'm always learning and talking to them. One of the interesting things about it is that most of the trombone notation, when you're writing the actual notes, is typically above the staff, which on a saxophone part would be in the higher register. But that's like in the meat of the trombone register, which is unnatural for me to read and think about as I'm composing.

Often, when I write, I like to double the acoustic bassline with either baritone or bass trombone, or sometimes both. It gives it just a little bit more punch and body on that low end, which I love. You'll notice that on some of the pieces, like the beginning of "Certified Organic," they're playing this line together.

Lawrence: I love the idea that the instrumentalists help you learn how to communicate with them and translate that into something you can put down on paper for them.

Sean: Oh, it's so valuable and it's cool how it lends into the idea of—well, the concept of this first album, the idea of community. That was one of the things I realized: if they notice I’m putting work into this music and they enjoy it, they enjoy playing, and they want to help me make the best arrangements, parts, and compositions possible. They're the ones playing it, you know, they can lend a lot to the outcome that's not just playing the part itself.

And it was funny, my drummer just had a birthday party and as sort of a joke gift, I made this part for him that was four pages of just what we call slash notation, which is just like blank measures with no description, like an early drum part I would've made before I knew what I was doing. Now I make good drum parts for him because he has taught me really what to do. But he was like, "That was the best gift." It reminded us of back when we started the band, and I was learning, and we all had a lot to learn. And so we've enjoyed that experience, and just sticking with it has been valuable.

Lawrence: Where do you compose? Do you write at a piano?

Sean: Most of the time, it is at the piano. I have hundreds of voice memo audio recordings on my phone, where, if I’m out somewhere, a melody, a bassline, or a rhythm might come to me. And a lot of times, I'll just sit down and sing into my phone, maybe ten or twenty seconds of a small idea. Then, often, I’ll sit down weeks or maybe months later and go through these voice memos, picking out the ones that still speak to me or that I feel have potential. And then I'll try to flesh them out at the piano. But a lot of times, yeah, I'll sit at a piano, especially if it's a nice piano that's in tune and has a nice sound. I can be inspired for hours and get lost. And sometimes I need to be careful. I'll even have to set an alarm if I need to leave to go somewhere, or else I'll just forget about my responsibilities.

The saxophone is a great instrument, one of the best, but—and this is one of the things I think about a lot—it lacks the ability to play actual harmony. I think about it as if we're implying harmony when we’re playing saxophone, but we're not actually playing it. Harmony technically is two or more notes played at once. However, playing a harmony instrument like a keyboard or piano, I can delve into the harmony, and I can also think about counterlines.

That's typically how I come up with the initial idea for a song. Once I have the basic idea, I try to expand it and blow it into a full-band arrangement. And that brings into play things like, "Okay, what's more of the style? What do I envision the drums doing? How do I envision the role of each horn section? And who's gonna have the melody when? And where do I want the peak to be?"

One analogy I like is the idea of a sculptor showing up and starting with a huge block of stone. Each day, they come and chip away a little bit more, a little bit at a time. And then the visual that they're trying to create becomes a little bit clearer after days and weeks. They're just chipping away and refining it into the exact thing that they have in their mind. And it was very similar to me, where you have this maybe big block, which is just the initial melody or just the bassline, and then you're chipping away to add elements to get it to sound like what you want it to be.

Lawrence: When you're working on your arrangements and your parts for the other instruments, are you hearing the music orchestrated before you hear it in the room with the players?

Sean: Sometimes I do. One thing that I am trying is not to use digital tools or DAWs as a crutch, although they are very valuable. I heard an interview with Maria Schneider, where she discussed how she never composes on the computer and instead sketches everything out. She's writing everything at the piano. And of course, you can hear chords and multiple layers happening at the piano, but it's not the same as hearing the timbres of the instruments.

But I do use Finale, although Finale is kind of going by the wayside, and there's a new program, Dorico, which is sort of taking over that landscape. Essentially, you can just plug in the notes for each instrument, and then it has a playback option that's pretty good, especially for horns. You hear the trumpets being played along with the saxophones and trombones, and you can add the rhythm section parts if you want, which for me helps a lot in terms of, “Does this arrangement have the clarity that I want? Am I hearing what I need at that certain time? Is there too much going on?" So I do use those, but I am always trying to build the sound of the piece in my head before I hit play on those tools.

Lawrence: Could you tell me about the preparation and logistics for recording sessions like these? We're in an era where it's not like there's a big major label budget that's just waiting to be spent by you. And I can barely organize a conference call with four people, never mind a couple of days of sessions with seventeen people.

Sean: For me, I'm high in what they call openness, which covers the creative aspect. I love sitting down at the piano, just coming up with ideas. I can do that forever. But then the other side of it is the logistics of making this happen—getting the funding together, the scheduling, getting all the musicians on the same page, and getting the rehearsals done beforehand so that we're really sharp in the studio. After that, it’s about getting the mixing and mastering done. This is my first project where I've gone all the way.

It’s about thinking ahead and then being very clear and concise with the details for the band. Right now I'm looking at booking a gig in November or December for the band, and it's like, "Okay, if I can nail down a date, I’ll check with key players in the band first"—lead players of each section and bassist and drummer in the band, making sure they're solid. Then I reach out to the full band in a concise email with the dates, time, and pay. "Here it is, get back to me in a few days," then boom, we book it with the club.

When it comes to the funding aspect, that's a tricky one. Yeah, no label is involved with this. We did get a lot of support from the community. We did a Kickstarter campaign, which helped a bunch. We have had a strong local following here in Indianapolis, where we perform at the Jazz Kitchen, a great club. And what I realized is that coming out of COVID, people were hungry for live performance. And so when we started booking, we began selling out our shows. And I was like, "This could be the springboard into what allows us to make our first album."

I was certainly doing it on the relative cheap side, especially compared to how the big bands in New York City are recording their albums. I mean, I've seen some of their budgets, and it's crazy how they're doing it. But there's a fantastic studio just an hour south of Indianapolis in Bloomington, Indiana, near Indiana University, with an incredible genius audio engineer. He owns the studio, and he's willing to give us a great price. And so with our Kickstarter campaign and then me just saving my pennies on my own, we were able to make it happen.

Lawrence: I'm curious about the producers on this record, Steve Allee and Rich Dole. How did they help you shape and capture the sound you were going after?

Sean: Well, both of those guys have so much experience. Steve Allee, I believe, is in his mid-seventies now, and he's been a professional musician his whole life. He leads his own big band, so he's been doing it for a long time and has a wealth of knowledge. Not about just the nuts and bolts of music, but just about the overall big picture—what do you want this piece to feel like? Where do you want it to go?

I remember a few times in rehearsal, we would play through something, and I would say, "Yeah, this feels good." And I was always checking with Steve, "What do you think? Do you have any feedback on this one?" And often, he would focus on general conceptual aspects, such as, "What's the volume shape that you sort of envision this chart to have?" Some of my charts are like a punch in the face, with high energy throughout, which I enjoyed because I felt that some of the other charts would balance it out. But he would say, "Okay, what about if this section, we even bring it down just a bit. Then, when we come to this big climax here, it'll make it even more powerful." These little shaping things would add so much musicality to the pieces.

It was funny; I didn't even ask Rich Dole to be a producer initially. After we recorded and I had initial mixes, I sent them out to the band and asked, "Anybody who has any feedback, send it my way. I want all of you to chime in if you have any information that you think is valuable." Rich sent me a detailed email with many great ideas. Rich has played in big bands forever. He's done a lot of arranging. He is a well-rounded musician with a wide range of skills. And so he would give me things like, "Oh, I can't hear the proper balance between like the baritone sax and the bass trombone and these four measures here." He is a trombone player, so he's giving me specific things there. So, Rich gave me so much that I was like, "Rich, I'm making you a producer without you even asking for it, because this is so helpful."

Lawrence: I wanted to discuss the overarching theme of Communal Heart. You talked about the Kickstarter campaign, and that certainly had a communal element to it. How do you cultivate a sense of community practically? How do you do that with the band and the audience?

Sean: The way I think about it, a lot of times with jazz, I feel like a lot of our role, specifically as a jazz musician, is to double down on our individuality. When we think about who we consider to be the masters—Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk—true individuals, and they went all the way in on what their singular soul and vision of music to them they thought it was supposed to be. And that's the thing I always stress with my students. And one thing that I try to do with myself is like, "What does my music look and sound like, and how can I double down on that?"

From there, I need to get it so that the musicians in the band, when I send out that email for rehearsal, I want them to be excited to say yes. I don't want it to be the thing where it's like, "Ah, Sean's charts aren't that great." So I was like, "What's in my control then to help them just to say, 'Yes, let's do this right away'?" And one of the big things is I need their parts to make sense. I need the whole picture to make sense. I want the music to be as good as it possibly can be. When I do that, it gets the musicians more on board, and it gets them excited to show up to rehearsal. So, then they get invested in the project; they’re putting in the work, practicing the charts before the gig. They show up to the gig, excited. We put on the best performance that we possibly can. After we do a few of those, we get a bit of a buzz. The word gets out. All of a sudden, as I was saying, after COVID, when we came back, we were getting crowds that I had not anticipated.

And I always think it's funny because some of my music is fairly dissonant, kind of abstract, maybe a little more modern than what the traditional jazz listener wants, but I don't care. As I say, I'm writing it for me. And if I double down on that and it speaks to me, I think it will also speak to a lot of people in the audience, which is what I was noticing. We were getting great responses after some of our concerts.

I just need my audience to be invested, no matter if it's small or big. I need those people to love it. And the way for me to do that is to make sure I'm doing everything I can to love the music that I'm writing, get the musicians involved, then get that crowd on board. Then, you have the two main elements of the community.

When the musicians are in rehearsal, we're joking around. It's like our second family in a way, which is great because we're all learning the music together. We're having fun, we're enjoying it, and then we get excited to play the gig. It's not just a commercial thing—we're showing up, we don't know anybody, we're not just doing it for the paycheck. Not that at all. We're very much invested in and about the music in that sense.

When the crowd comes, they see that we’re invested; they know that we're trying new things. Every time we play, I have new music that we're putting on, too. So they're excited by the surprise of hearing the new sound, something they’ve never heard before. And especially when it comes to the solos, they don't know what's going to happen. And there's always this level of excitement.

Then it’s time to ask, "Hey, do you want to be involved in helping fund this project?" I think we had over 120 backers in the Kickstarter campaign. I think I set the Kickstarter goal for $20,000. I was like, "There's no way we're gonna raise this money." And I was just doing it like a Hail Mary. I didn't think we would get it, but I was blown away by the support that we got. That gives me a lot of confidence in terms of, "Okay, this idea of just trying to double down on my musical vision does sort of touch people and connect with people in ways that I can't imagine until we just perform and see who likes it."

And it's always funny because sometimes after a show, I'll be hanging out with people and ask, "Which song stood out to you? Which one did you like?" And sometimes the answers are not what I would expect. It'll be pieces that I think are more dissonant. They're like, "Well, I just love the energy and the rhythm behind that one." And I'll think, "Oh, okay. Wow, that's great,” because it's not one of the more palatable pieces. So yeah, it's just being open and willing to be yourself and knowing that that will connect with people and not trying to conform when it comes to art. That's a tough stance to take, but I think it pays off, and people enjoy the individuality when they hear it.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments