Music, especially the instrumental and introspective kind, has an uncanny ability to conjure images of physical space, a sort of sensory overlap. However, it’s challenging for those implied images to convey motion without, for instance, a lyrical narrative. Water is a common and useful analogy, as we already use words like "flow" to describe progressions in songs.

With Chaz Underriner's recent album, Moving, running water, in an environmental setting, distinctly provides direction. The waterways of the southern United States, including Blue Springs in Florida and the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana, serve as the primary source of inspiration, as well as the source of occasional field recordings. Sonic elements create ripples that expand outward, colliding with others to form unexpected patterns.

Moving represents five years of composition and collaboration spanning from 2018 to 2023. Initially commissioned by Belgian guitarist Nico Couck following Underriner's well-received Landscape Series: 1 at Gaudeamus Muziekweek 2017, Moving evolved through several iterations and collaborations before emerging as a 50-minute multimedia composition. The work features Couck on electric and pedal steel guitar alongside the acclaimed Ensemble Modelo62, with five video projections and 10.5 surround sound creating an immersive sensory environment.

What began as discrete commissioned pieces—including works for the Wet Ink Ensemble and the Moscow Contemporary Music Ensemble—eventually coalesced into a unified whole that Underriner describes as "modules, blocks of different pieces to arrange and overlap over time." Released on Underriner's newly established Deadland Records, Moving presents a condensed journey through this sonic architecture, with album art by designer Lee Tesche that transforms Underriner's video art into a visual companion to the recording.

At its core, Moving explores phenomena like the wagon wheel effect, acoustic beating, and "multiple simultaneous microtonal compositions"—Underriner's interpretation of Charles Ives's multiple-pieces-at-once aesthetic. The work shifts between sparse, meditative passages and dense, orchestral textures, creating what Underriner calls “a kind of visual” experience through sound. From the majestic resonance of organ stops in "Color Study" to the ambient field recordings of "Swamp," each piece within Moving represents a unique approach to composition and aural visualization while contributing to a cohesive artistic statement.

The album follows performances at Gaudeamus, Orgelpark Amsterdam, and The Hague in 2023, a distillation that preserves his structural vision while offering listeners a new way to engage with his multidimensional art. I spoke with Underriner about the conceptual foundations of Moving, his collaborative process, and the challenges of translating a multimedia performance into a recorded artifact.

Michael Donaldson: This album draws inspiration from specific southern waterscapes, such as Blue Springs in Florida and the Atchafalaya Basin in Louisiana. What drew you to these particular bodies of water?

Chaz Underriner: These are waterways that I've spent time in. Blue Springs is close to my home in central Florida, and it's known for being a refuge for manatees in the winter and for swimming and scuba diving in the summer. I did some underwater and above-ground field recordings for this album in Blue Springs. For both of these waterways, I was attracted to them because they are prominent public resources—natural springs that are protected as a State Park in Florida and the Atchafalaya as an important wetland in Louisiana.

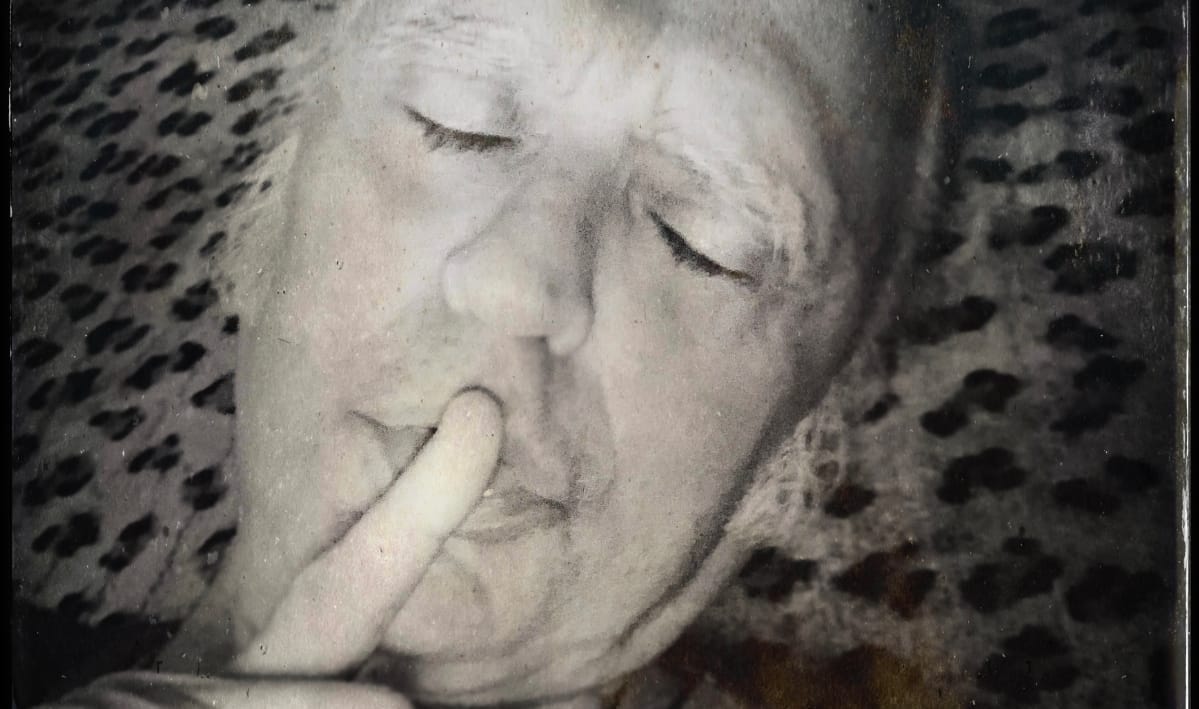

I had the idea to shoot some video in Atchafalaya, inspired by my experience driving on I-10 from Florida to Texas. In Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, there are miles and miles of bridges going over the swamp. I had the idea of going under the bridge and shooting video, traveling underneath it as a sort of hypnotic moving image. A still image from that video is the cover art for the album, and you can see all these high-water lines on the pillars of the bridge from historic floods in the area.

To shoot the video, I hired two Cajun guys, a father and son, to take me out on the wetlands and drive me around. They've done this for visiting photographers, but I think I was the first to specifically shoot the bridge in addition to the swamp. They told me many interesting stories about the bridge and the swamp. There's a story that if you see a ghost walking on the bridge, you'll crash your car and die, for example.

Michael: The album’s title, Moving, operates on multiple levels—referring to physical movement, emotional response, and changing position. How did you explore these various dimensions throughout the album?

Chaz: Moving through landscapes is fascinating to me. I grew up overseas and traveled a lot as a kid, so I always watched different environments pass me by as we drove and flew around. This made a big impression on me. I still have memories of driving past different cities, landing in airports at night, and seeing the city lights, something I've always thought was so stunning. So, I connect an emotional response with moving through spaces themselves.

I always feel like an outsider moving through landscapes; they're never mine. Instead, it feels like a gift to be in the world. In this piece, I was also interested in visual aliasing or the "wagon wheel" effect when things move too fast for a camera to pick up and create different types of strange motion. I recorded sound and video of wheels spinning in my studio and used those recordings in the video art and electronics of the album. This reminds me of riding in a car and spacing out while watching the wheels spin in the cars next to you, something about travel I always thought was hypnotic.

Michael: How do you translate the physical and temporal experiences of natural landscapes into sonic experiences?

Chaz: I translated these spaces into art in an abstract way rather than directly into sound or music. One thing I did with the Blue Springs recording in "Moving for Modelo" was to go from underwater sounds to above-water, then back to underwater throughout the piece, creating a spatial structure for the track. The musical sounds I wrote are more inspired by the vibe of the spaces, especially in the early morning or late at night.

Michael: I’ve been to the Atchafalaya Basin many times myself, and have noticed how it’s simultaneously wild yet deeply shaped by human intervention through flood control systems. Did this tension between the natural and the human-engineered show up in your compositions?

Chaz: Geographer Hildegard Binder Johnson wrote, "Landscapes need the subjectivation of nature," meaning that "landscapes" do not exist without human observation to put a frame around them. Outside of human perception, nature exists on its own terms with its complex systems. So I think the tension between humanity and nature exists even more fundamentally than in human intervention in different ecosystems; it also exists in our perception of nature as an entity in the first place.

For me, creating landscapes is all about subjective experience, since it’s more or less impossible to present nature “as it is.” And blending field recording with composed elements is a way to utilize environmental sounds (in a subjective way) to create a landscape piece of art.

Michael: Many southern waterways exist in a state of environmental precarity due to climate change, pollution, and development. Do you see your compositions as documents of places that might fundamentally change within our lifetimes?

Chaz: All of the waterways I used in the album require preservation efforts to protect them from the effects of climate change and human consumption. For example, Blue Springs is affected by runoff of all the toxic chemicals people use to kill weeds in their yards in central Florida.

I'm not trying to create a data set for researchers to build analyses of different environments in my work, although this is important work in Acoustic Ecology that is useful to scientists. To me, to make art that involves landscapes is to document what is vanishing—we as humans have limited life spans, and the environment itself is affected by our actions. I'm drawn to the Japanese aesthetic of mono no aware, the pathos or emotionality of things, the beauty of the transience of life.

Michael: Also, I should mention that the South has a complex and layered history tied to its waterways—from indigenous relationships with water to colonial trade routes and plantation economies. Do any historical resonances find their way into this work?

Chaz: I think it's interesting that human history occurs in the same places at different times. These waterways in the south have been used for different purposes by different populations throughout history; they've been transformed by human intervention, yet they still exist despite all that. How the world can persist for so many generations of human culture makes me feel awe.

I don't think about any one historical point in my work, but I try to be aware of and imagine the whole history of a place. How many lives has this body of water touched? How much of human history has been supported by this body of water? Can I catch, hold, and perceive these memories? Does the body of water remember us?

Michael: You describe your approach to Moving as working with "modules" or "blocks" that overlap in time. Could you talk about how this modular construction relates to your experience of landscape?

Chaz: My experience of landscapes has a lot to do with moving through them—walking, swimming, driving, riding on a train. Whenever I'm moving through a space outside, I have a collage of thoughts: memories, tactile feelings, small thoughts about my day, my mood, seeing and hearing details in the space. The physical place I'm in and how I move through it affect my mental experience, sort of coloring the collage of my thoughts.

Michael: Is there something about how you move through spaces that inspired this structural method?

Chaz: I think the technique of composing with modules, of different layers that are in dialogue with each other comes from the way my ADD brain works and also has some musical inspirations; the way that electronic music can generate lots of interacting layers in a DAW and the way Stravinsky worked with "cells" of musical ideas in pieces like the Rite of Spring, cutting them all out on small sheets of paper and moving them around on his desk to find interesting combinations. I think our brains always have a multiplicity of thoughts and memories overlapping, so why not compose like that too?

Michael: Regarding the short composition "Zimbelstern," you mention using your written material as a "jumping off point for group improvisation." How do you navigate the balance between your composition and allowing space for a performer’s agency? And what role does chance play in your process?

Chaz: I work with so many fantastic performers that it's a joy to trust them to create something together. I don't use many chance procedures in my work, although much love to John Cage. To me, the balance is slightly adjusting the parameters that performers work under to create an interesting whole.

For "Zimbelstern" on the album, the first interpretation is to play off the score I wrote: a bunch of accelerating and decelerating phrases based on G-F-E-D-C that overlap each other into many layers. Then Ezequiel Menalled (the director of Modelo62) and I started tweaking the prompt—what if we open up the musicians to use different pitches? What if we let them play in different ranges of their instruments, with the order of the pitches, to create different phrases and speeds? In other parts of the piece, we have the musicians approach the same material in different ways.

I love how this gradually opens things up, showing more of the group's personality as a musical entity rather than something strictly controlled by me. Part of my process is to bring ideas to the table with collaborators and then play around and see what we can come up with in the moment.

Michael: What attracted you to the pedal steel guitar for this work?

Chaz: I love the color of the pedal steel guitar. I also love microtonal music, so it's a natural instrument to work with—it's so easy to explore tuning possibilities. If I'm listening to country music, I'm almost exclusively checking out what the pedal steel is doing, and it adds all the flavor and texture for me. I bought the instrument that I composed on and that Nico played from my friend, the composer Christopher Trapani, who also uses many stringed instruments in different microtonal ways.

I think "Swamp" relates quite strongly to roots music, just filtered through my imagination. The kind of crying sound that the pedal steel can make is so guttural, and the bends and slides of the instrument are so expressive. To me, the music is like if a pedal steel player set up his instrument at the edge of the water at 2 a.m. and played his instrument like a kind of prayer.

Michael: You've mentioned being influenced by Claude Debussy's orchestration techniques in "Swamp." Are there other artists who inspired you in unexpected ways?

Chaz: I emulate other composers all the time, and other people rarely hear it (or comment on it), with the possible exception of Morton Feldman's music. I wrote one piece in grad school that directly related to Arcangelo Corelli (one of my favorite composers). But when I told that to one of my professors who knows Corelli quite well, he had no idea that's where I was coming from. All that to say that I'm not sure if other people can hear or see my influences very well since I'm constantly filtering them through my own artistic language.

In this album, I was using techniques from Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, Nissim Schaul, a friend of mine who wrote a piece some years ago that strongly affected me, and the pacing and evolution of Morton Feldman. At this point, these historical techniques come and go as I'm writing. I often use the Renaissance contrapuntal techniques of talea and color, for example.

Michael: There's a rich tradition of artists responding to the American South's waterways—from literature to visual art to music. How do you see your work in relation to this lineage?

Chaz: I'm proud to be an artist from the South who makes more experimental work. There are many, many artists from Texas (where I'm from) who leave for their artistic careers—Robert Rauschenberg and Ornette Coleman come to mind. I think it's great that more avant-garde or whatever you want to call contemporary artists are sticking around the South and making interesting things here. Music and art aren't just from New York.

Visit Chaz Underriner at chazunderriner.com. You can purchase Moving on Bandcamp or Qobuz and listen on your streaming platform of choice.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments