What do William Penn and Jeff Bezos have in common? It's unlikely that question has troubled many minds, but it's the foundation for FARMING (released via Deathbomb Arc), the latest album of a work by composer Ted Hearne. Commissioned and performed by the choral group The Crossing and their director, Donald Nally, it brings together Penn and Bezos via settings of their own words. And it turns out, they are natural companions, especially when it comes to exploiting people and resources for their own gain.

"The idea for the central, returning focus of some of these songs is a conversation between William Penn and Jeff Bezos," says Hearne. "That comes from working with The Crossing and having the premiere happen in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, at a farm one mile from where the Walking Purchase [the agreement between the Penn family and the Lenape people that ceded land to Penn] was signed, and seeing the low-key deification of Penn that still exists in Pennsylvania as a 'good colonist,' the fantasies of benevolence that surround him in terms of, he's nonviolent, and he's a Quaker. He's just trying to get along with everybody. But of course, he's asserting ownership for the land."

Hearne, speaking from his home in Los Angeles, adds, "That reminded me of some of the narratives that propel some big tech guys, the people that are running some of these organizations, and the way that narrative helps them create and sustain certain labor practices. And Bezos seemed like a really good pairing with Penn because of that expansionist philosophy, the way that he positioned himself politically, pre-Trump II. And it was really interesting to start looking at their writings and their speeches and putting these words next to each other. That's something that really got me going."

The title is more than the literal premiere performance site, and there's nothing in the music about sowing, reaping, farm tasks. Unless you think of farmland as a digital space, and listen to The Crossing singing about "farming" digital tokens, wringing music out of engagement-farming tweets, deliver a comforting, upbeat anthem on how "all results" for "H-2A temporary guest worker / reliable seasonal workforce . . . service provider . . . providing seasonal ranch workers." And on a granular level, Hearne points out that some texts "come from these corporations that are dealing in some way with the food business.

"We have a language that's modern and corporate and hyper-pop focused," Hearne points out. "And then we also have this colonial language, you can hear phrases like, 'My God gave me this land,' essentially to do what I want with it, and, you know, they named it 'after my father, Pennsylvania.' That very attitude is related to this idea of, 'I'm a billionaire CEO, and growth is the only goal, profit, I am endowed to create this growth.' That is settler colonialism; that is the same mentality. The music creates these opportunities where these juxtapositions are maybe confusing at first, but that connection is there."

This is political music, and Hearne is one of the premier political composers in the contemporary Western classical tradition. His 2010 album Katrina Ballads is a theatrical song cycle that sets the words of New Orleanians who survived the horrendous flooding from Hurricane Katrina, interview dialogue between Anderson Cooper and Senator Mary Landrieu, and the infamous "Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job." The combination of the banality of the powerful and the tragedies of the powerless is infuriating and heartbreaking. The Source is an electro-acoustic oratorio that uses more source documents to narrate the story of Chelsea Manning, and his first album with The Crossing, Sound from the Bench, has a libretto he put together from the Supreme Court opinion in the Citizens United case, excerpts from Jena Osman's Corporate Relations—poetry about corporate personhood—and words from ventriloquism textbooks.

There is something abrading and acidic about that last detail, like Hearne is the ultimate irony-poisoned cynic, and there's plenty of irony and satire in his pieces, and in FARMING, but his music is something beyond, and outside, of both the qualities. There's no easy scorn or laughs; instead, FARMING is as sincere and guileless as it gets. It's political classical choral music as American vernacular techno-pop. The music works, so the politics work.

Politics ain't pretty. It never has been, at any time in history, anywhere in the world, and certainly not America in 2025. Most of this comes to us through the news and social media, and it is ugly almost all the time. Political art has to contend with this ugliness, not just as subject and source, but as a thing to be somehow rearranged and re-engineered into something else that's not necessarily prettier or more appealing, but that can communicate something that's affecting and meaningful through that. That makes political art a challenge to pull off, on top of the already immense difficulty of the task of being meaningful and affecting, not just as a statement but as art.

There is a lot of art, or music, that says something political and very little of it that can change hearts and minds, move actions, and also works as music, and crucially has a meaning that cannot be misunderstood. Take the Italian song "Bella ciao:" it has roots in the 19th century as a work song for the poor women who labored in the rice paddies of Northern Italy, and then became a left-wing song starting in the mid-1960s, retroactively ascribed to the anti-fascist partisans before and during World War II. Flexible enough for politics to be loaded into it, for it to appear in the Money Heist television show, for Marc Ribot and Tom Waits to record it, for Italian unionists to use it to protest Giorgia Meloni, and for the video game Helldivers 2 to use it ironically in a pro-authoritarian context [now made infamous by Tyler Robinson]. What does "Bella ciao" mean? Apparently, whatever someone singing it wants it to mean.

That's one of the traps of political art. Another is that it's easy to use a medium to frame a slogan, like "corporate exploitation is bad," but doing that doesn't make it art, much less good art. The experience this past summer of a left-wing musical artist name-dropping Luigi Mangione—anti-woke at best—was a deflating case of a performance eviscerated by sloganeering. There's an essential quality that political art needs as a foundation to work, which is a clear moral and ethical vision that then sidesteps any promotion of political systems and instead bears witness to things that are wrong on a fundamental human level, and by working as art, shows the extraordinary counterexamples of creation, collaboration, expression, communication, humanism. Political art that works has values, uses them to judge what's wrong, and to show what could be right.

In music, the great examples are the operas of Mozart and Beethoven and Verdi, "Strange Fruit," "This Land is Your Land," Charles Mingus' "Fables of Faubus," Max Roach's We Insist album, "War Pigs," Fred Rzewski's “Coming Together” and “Attica.” Now, add FARMING to those.

Asked about who he imagines listening to this music, who the audience is, who he might be trying to effect, Hearne says, "I think there's two types, there's the people who are part of making the music, and the huge part of that is The Crossing, who are engaging with a tradition of classical choral music in contemporary music, and composers who are writing in that medium. I think almost, if not always, it's non-religious music, it brings you into this space that's secular, liberal, people that are mostly wealthy and from . . . I mean, The Crossing originated from the suburbs of Philadelphia. Of course, they have national reach, because they're a great choir, but the origin of the piece comes from working with that ensemble—they commissioned it with the idea of writing a piece to be performed on a working farm that deals in some way with 'farming.'"

Hearne was interested in who The Crossing's typical audience might be, "where are they coming from, and what does that world mean to those people? Or what does it mean to bus a bunch of people from the city out into this space?"

There's not just a socio-economic but an aesthetic component to his questions. What do people expect from a choral performance? Hearne is one of the classical composers who comes out of the early 21st-century indie-classical scene, seeing pop and classical styles as inherently malleable and also using modern production technology as something like an instrument itself in his orchestration. That means FARMING is dense with the brightness of auto-tuned and harmonized voices.

But Hearne wasn't only thinking of a classical music audience. "I'm completely fascinated with and interested in making music for an audience that doesn't engage with live music like that at all," he says, "like people who are listening to electronic music, listening to albums. And this movement of people who are making music from their homes, on their own. That digital space, I'm really interested in, a space for incredible sonic innovation."

The political part is "criticism of the world that we're in, which is something that I love about art. So, long answer, I was interested in fusing those audiences, not pitting against each other, but where they can coexist and [then be] integrated into what the music is.

"Sometimes the rhythmic setting might be jarring, or might signal something like that's outside of contemporary pop music. But then sometimes it references an older form of pop setting, all those different degrees of referentiality are a part of the setting."

The sound of all that has a boost from composer William Brittelle, a colleague from the Brooklyn scene, who's becoming an increasingly active and accomplished album producer. "He's an old friend," Hearne says, "and he's been getting more and more into production, on his own work recently, but then also a couple of Roomful of Teeth albums. He's reinventing how to produce with a composer's brain. We spent a good year making the album what it is, because there is so much communicated in the production."

Those details are for the modern ears to get into the classical side of the music. The sonic signifiers of contemporary pop production are something of a hook that reels someone into "the mixture of styles, a hybridity or fluidity," that Hearne "used for its political import, as a means of text setting. We have to look at minimalism and post-minimalism . . . early Glass and Reich incorporated all these ideas from different non-classical styles, but they were writing in this sort of modernist severity. All these post-minimalist offshoots are more easily commercially appropriated, because there's something fun about the music."

Mixing together choral singing, vocal solos, and spoken passages also gives this the feeling that different characters are in the piece, directly addressing the listener. That's pretty much the point, as Hearne says: "The Bezos stuff, some of that is from a statement he gave when he was testifying to Congress. The other texts are all extemporaneous, spoken words. Then there are tweets and stuff like that. When viewed with the music, it creates a super complex persona, or unreliable narrator."

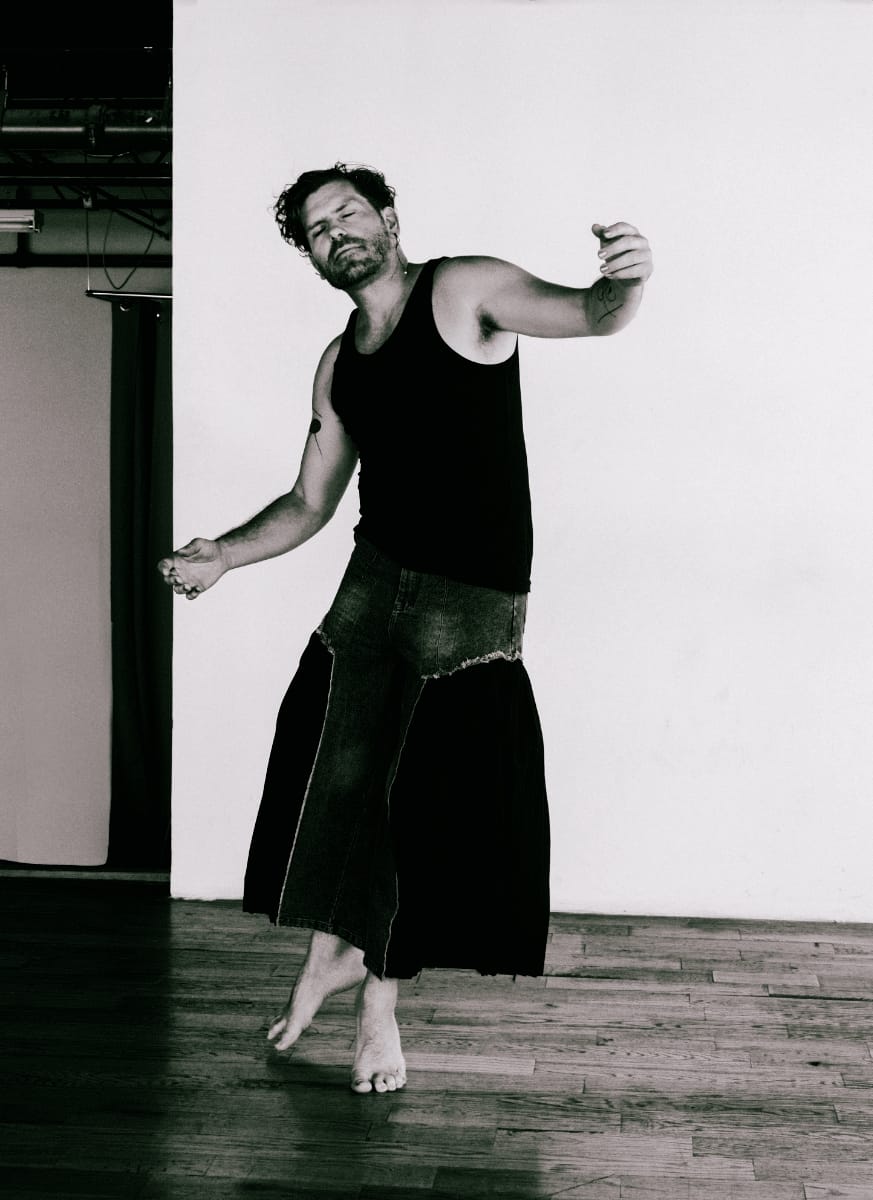

Photos by Dana Scruggs

The existence of this album in America in 2025, and the specificity of William Penn, Pennsylvania, Bucks County, is, in a metaphorical and elusive sense, a statement about the end of the myth of social mobility, that Americans can just move around easily for better opportunities. Any University of Chicago economist will tell us that our problem is that we're not moving to the right places. But they have no idea what that actually means. In a low-key way that is still pervasive across the album, FARMING puts that perspective to music, how seeing people as faceless resources to exploit comforts one in blithe ignorance. By clarifying who these people are and what they think, through their own words, the album is paradoxically uplifting, like it's arming the listener with the tools to fight.

"In the last track ('We're Actively Monitoring'),” Hearne explains, "the text [is] all the tweets that Uber Eats put up following the pandemic, basically over the year they opened their delivery services . . . every tweet where they use the words 'we're doing this, we're doing that.' This is summer 2020, where it's the height of corporations adopting the voice of social justice or something. Everyone is standing in solidarity with these movements, thereby completely obliterating the meaning of what the movement is.

"And then one of the tweets is about freedom of movement, like, 'We're pledging that everyone has the right to freedom of movement.' We're pledging rides and meals. So this is like hashtag-pride. The first hashtag-pride was a protest led by queer and trans people of color. 'Everyone should have the right to move freely, we're pledging to donate,' whatever. It's a PR tweet," promising everything and delivering nothing, with a smile.

"When I read it," he goes on, "I'm like, of course. But then the tweets that it's next to talk about a great mom, and like, a tackle emoji, or whatever. You're not serious people! This isn't real! Freedom of movement is really important. We technically have it. So, why don't you just do it? That's the gig economy, right?" Right, and in that, we're either the ones being farmed or the ones doing the farming.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmArina Korenyu

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments