Busy and vital as ever at age eighty-three, John McLaughlin is currently overseeing two new album releases. Montreux Jazz Festival 2022 is a 2CD+Blu-Ray document of the virtuoso guitarist with his longtime band, the 4th Dimension. On thrilling, fiery tracks like "Kiki," the quintet—McLaughlin plus Étienne M'Bappé on bass, keyboardist/drummer extraordinaire Gary Husband, pianist Jany McPherson, and drummer Nicolas Viccaro—wipes away any perceived lines between blues, jazz, and fusion. The set features twelve tunes, ten of which are McLaughlin originals. Also featured is a transcendent reading of Pharoah Sanders's sublime "The Creator Has a Master Plan."

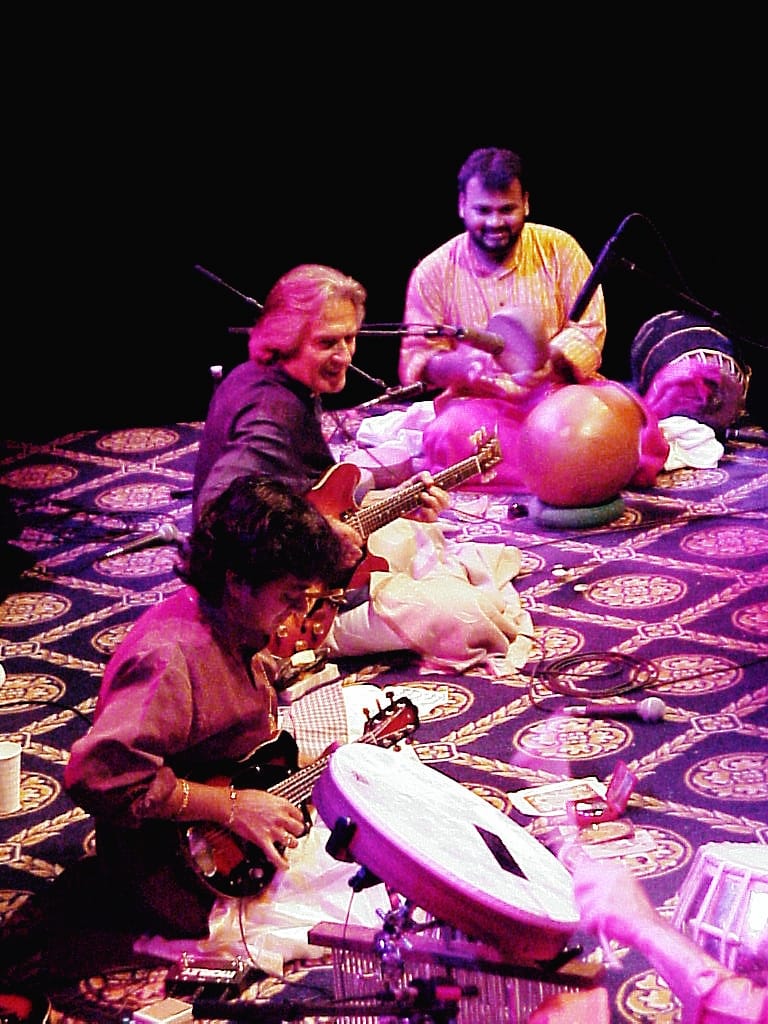

McLaughlin seems to have a master plan all his own as well. In the early seventies, and alongside two other major endeavors—a thriving solo career and leading the groundbreaking Mahavishnu Orchestra—he launched Shakti, one of the first-ever 'world fusion' groups. Seamlessly combining Eastern and Western musical sensibilities, the ensemble featured McLaughlin alongside some of India's most revered traditional musicians. Their sonic synthesis yielded several acclaimed tours and three albums released during that decade.

Inevitably—owing to the busy schedules of the involved parties—Shakti was an intermittent project. After a lengthy hiatus, McLaughlin and Shakti mainstay Zakir Hussain reactivated the group in 2023, earning a Grammy Award for This Moment. Hussain died in December 2024; shortly thereafter, McLaughlin announced that Shakti was done. But Mind Explosion, a recording drawn from the group's triumphant fiftieth anniversary tour, serves as an exclamation point at the end of the Shakti saga. It's also meant as a tribute to Hussain, McLaughlin's longtime partner in that musical endeavor.

Though he's a willing, lively, and engaging interviewee, John McLaughlin has taken part in comparatively few interviews focusing on Shakti. So the opportunity to speak with him about that group was a treat indeed.

Bill Kopp: What was your first exposure to Indian music?

John McLaughlin: Oh, my; we're going to go back to the sixties! Probably it was one of the Beatles’ tunes where George Harrison was playing sitar. But then around 1967, I heard a South Indian veena player called S. Balachander; he just blew my mind. And this also coincided with the psychedelic period; we were all tripping ... legally, of course. And it coincided with my desire to discover something about the meaning of life, as they say.

But from that point, hearing Balachander and the South Indian school, which he was part of, was more than fascinating. It just grew. I moved to the U.S. at the beginning of ’69, and by the time I got to New York, I had already started to look for a teacher to teach me Indian theory. Either North or South; I didn't care. And it was that summer that I got to meet Zakir Hussain for the first time. And the rest is history, really.

Bill: What was the inspiration to launch Shakti?

John: Because they were amazing players. The Indian musical system, whether North or South, is linear; they don't have harmony, but they have among their musicians some of the most unbelievable improvisers. And that's the key word, because other than jazz, they're the only other school that improvises rhythmically.

And that coincided with a very curious phenomenon in 1958 when Miles [Davis] came out with the new modal system of playing. When I heard that for the first time was on Milestones; that came out in fifty-eight. I would have been sixteen, and I knew that this school was for me. The great thing about the modal school is that it's also linear. Coltrane made his own version of that with "Impressions." He took the structure right out of Miles's book.

We in the West use harmony. But what changed for me was that I saw everything—even harmony—in linear terms, and that was a big change for me. Instead of seeing it vertically like a chord, I just saw a chord like the same notes of a scale, or whatever mode played simultaneously. So that loosened everything up for me.

But the thing is, the Indian players are not only master improvisers, they're master improvisers in very odd time signatures, which has been my personal fetish since I was very young. And this continues to this day; I can't help it. Especially if I'm using a harmonic structure, [I enjoy] the challenge of playing in, say, five or fifteen or eleven or whatever, with not just a rhythm—that rhythmical restraint—but the harmonic restraints.

It goes back to this quote of Stravinsky I read. He said [paraphrased], "The more restraints I put on myself, the freer I become." I think this is where discipline comes in. Because in the end, I'm a firm believer that perfect discipline will lead to perfect freedom; that's the way I see it.

Bill: You talk about the linear nature, the commonality between the two forms, jazz and Indian music. When you put Shakti together, did you find that you had to make any concessions to either approach to make them work together?

John: No; it fell right into place. Because at that time—and it's continued to this day in the development of Indian music—Indian musicians were as fascinated about Western music as I was about their music. Especially people like Zakir Hussain or L. Shankar, the violinist whom I met at Wesleyan University, where I was studying veena with Dr. Ramanathan.

Part of my goal as a Western musician was to be able to move to a certain degree harmonically. I was playing notes that were not in that specific raga they were playing, but they were the right notes, whereby I could enhance a solo by bringing in another kind of color behind their solo. The Indian musicians really liked that, where I would [add] another color. Even though they were playing the same raga, it sounded differently because of the fundamental.

And this developed to the ultimate point when a few years ago [2020] I made an album with Shankar Mahadevan and Zakir called Is That So? For years, I'd been wanting to do this experiment; that was part of my goal playing. I would ask Shankar Mahadevan to sing me an improvisation or ghazal, some devotional traditional tune. I started with one minute and thirty seconds with the tambura on a separate track, so I knew what his tonality would be. I heard it, then I threw it away. And then I began harmonizing, orchestrating what he was singing.

And of course, he heard it and he freaked and said, "John, we have to absolutely do this." It was over a year's work putting it all together, but this is a milestone in my life because it's exactly what you were talking about. And I think if you listen to that—even if you just listen to the first tune, "Kabir," [which is about] a beautiful human being—you'll get it; you'll know exactly what I'm speaking about.

Bill: Mind Explosion is in part a celebration of Zakir Hussain. In what way do you think that this new live album celebrates his life and artistry?

John: I think because he loved to play. Zakir would do classical concerts. Just like Shankar Mahadevan, who joined the band in 2000 and only about six, seven years later became absolutely famous; I think he's done over two hundred million sales in India. For both of them, Shakti occupied a very special place in their hearts. They were building bridges to me, as I hoped I would build bridges to them.

And through the music, I became much more aware of this fabulous culture that is India, the musical culture in particular. But also, I became quite involved in the metaphysical side of India, which they've been addressing for at least four thousand years. Because in the 1960s, you know, we were all looking for answers to these great existential questions. And we ended up, most of us, looking east in general and to India in particular, because they've got the answers. It's as simple as that.

Bill: How has your involvement in Shakti informed your approach to your other work outside that group?

John: Oh, indisputably. It's impossible for me to separate my influences. Sometimes I'll play something, some R&B, which I love. I still love to play rhythm and blues, but somewhere I know India is in there.

My mother had tried to teach me violin, which I hated. I hated my sound, so she let me study piano, which I did from six to eleven. I was very fortunate in having elder brothers who took my musical education upon themselves, having seen the passion that I had for the guitar at eleven years old. From that point, the guitar came into the house, and they took over.

And they, in their infinite wisdom, introduced me immediately to the Mississippi blues. And that went between Muddy Waters, Lead Belly, Bill Broonzy, and Son House. [When I was] fourteen, they decided they were going to introduce me to flamenco music, which marked me forever. And it's because of that I found a brother musician in the flamenco world, Paco [de Lucia].

And all of these influence [me]. And don't forget, I'm a Western musician; I started playing Mozart and Bach. These influences are behind the fact that I ended up doing two pieces for guitar and orchestra, and other orchestral things that I've not even recorded. But that's part of my musical life, and I love it. I'm a real mixture. Fusion is my middle name, without wanting it to be so.

I think I'm just extremely fortunate—privileged, even—to have had these marvelous musical experiences with people like Zakir Hussain, Shankar Mahadevan, and Selvaganesh. In fact, there will be, in December, another memorial for Zakir where we will all be with lots of Indian musicians. It would be the anniversary of Zakir's passing. We'll be on stage and there'll be a light where Zakir sits, and his tabla. We'll have Selvaganesh, the mridangam and kanjira. And we'll have for every tune, a second percussion player sitting next to Selvaganesh, because we play with two percussionists, North and South.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments