Toronto's jazz scene has watched Harrison Argatoff work backwards for the past five years. While most saxophonists in their late twenties consolidate skills and build reputations, Harrison has been systematically destroying his technique and starting over. The decision has cost him the fluency he spent years developing. It has also made him one of the more interesting voices on his instrument, someone willing to sacrifice short-term gains to invest in long-term understanding.

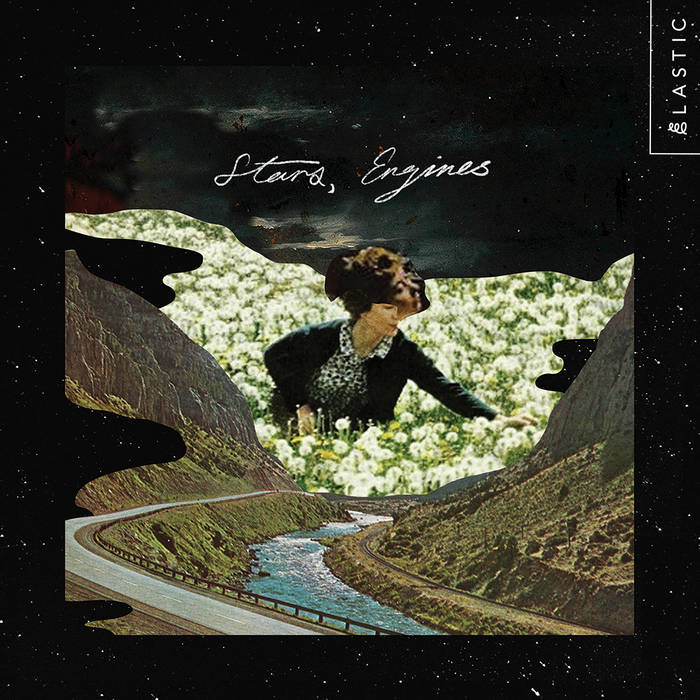

Harrison's album, Stars, Engines, documents what happens when a composer sets constraints for his bandmates and then steps back. His quartet Valley Voice features three musicians—Michael Davidson, Dan Fortin, Ian Wright—whose experience dwarfs his own. He chose these players because they could turn hastily scribbled shapes into rich music, refracting his interest in chamber music's precision through the prism of jazz's requirement for breathing room.

The album title references a moment that probably seems minor to most people: his grandmother woke up at night, looked at the stars, and heard trucks in the valley. Argatoff turned it into a lullaby. The transformation of taking a quiet observation and making it musical without inflating its importance runs through his work. He grew up Doukhobor in British Columbia, studied contemporary dance in Toronto, and teaches saxophone with obsessive attention to embouchure mechanics. Each of these elements feeds directly into how he thinks about sound, structure, and what the saxophone can accomplish.

Lawrence Peryer: You've spent years studying with Wallace Halladay and previously worked with legends like Dave Liebman and Mike Murley. How has your relationship with the saxophone changed as you've moved from studying jazz tradition to developing this more chamber music–influenced compositional voice?

Harrison Argatoff: It’s changed dramatically over the past five years, all thanks to Wallace Halladay's teaching. After I finished my jazz degree in 2018, I started to notice surprisingly large gaps in my understanding of the instrument. One of my most frustrating limitations was that a slow, simple melody, played softly, in tune, and with an even timbre, was unbelievably challenging to execute. This led me to Halladay in 2020.

In our first lesson, I was immediately struck by the unbelievable ease with which he played and the clarity of his technical understanding. His approach was simple: create an embouchure that balances four key elements—lips, tongue, jaw, and airstream—then move your fingers and let physics do all the work. Watching him demonstrate by playing virtuosic exercises with no visible changes to his embouchure immediately hooked me.

With Halladay's support, I painstakingly unlearned, dissected, and reconstructed nearly every habit I had developed since beginning to play as a child. During the first two years with Halladay, I worked exceedingly hard to sound steadily worse, as the restructuring resulted in losing touch with my previous skills. Since then, I've been slowly rebuilding my technique and discovering much more of the saxophone's potential.

Where many of my jazz teachers approached the saxophone with reverence, Halladay is pragmatic. He regards it as a tool, a tube with holes in it, an amplifier. Coming from the world of jazz saxophone, where players constantly adjust their embouchures, I'm continually stunned by the steadiness of great classical players. For anyone curious to see the difference, compare Michael Brecker's 1988 video of “My One and Only Love” with Arno Bornkamp's 1991 rendition of "Fingers" with the Radio Chamber Orchestra. Brecker's chin is constantly moving to facilitate playing in different registers and dynamics, while Bornkamp's face is nearly still throughout. This efficiency has captivated me these past five years.

Lawrence: I have spoken with many artists who have studied in one way or another with Dave Liebman. Could you share a story from your experiences with him?

Harrison: Dave Liebman is an amazing storyteller. Though this quality is apparent throughout his music, I've found it particularly captivating when he speaks. Liebman's presence fills any room, and his voice commands people's attention with its sense of gravity, of matter-of-factness.

My fondest memories of Liebman's teaching are in the stories he told about his life, his philosophies about art, and his relationships with the jazz greats. A story I've heard him tell a few times involves Miles Davis punching him in the stomach to check if he was 'hard' enough to lead his own band. And, though the story itself is interesting, it's Liebman's telling of it that stays with me. He made me feel like I was there alongside him, climbing the stairs of Miles's apartment, feeling the anticipation of Miles's response—pow—the surprise of his attack. It felt like Liebman could plug me into the jazz lineage directly with stories I'd gladly listen to over and over again.

Lawrence: You mention your work as a contemporary dancer, influencing your phrasing and musical momentum. That's not something you hear about often from instrumentalists.

Harrison: My progression in dance over the past ten years has been unexpected. What started in 2016 as an in-class activity eventually led to studying yoga, street dance, the Alexander technique, contact improvisation, and the Axis Syllabus.

Most notable among my teachers is Kathleen Rae, artistic director of Toronto-based dance company REAson d’être dance. Her teaching style shares many similarities with Halladay's—highly detail-oriented, teaching movement with precision that continually challenges me. The dance style Rae teaches is inspired by the Axis Syllabus, a compendium of information about the human body drawn from anatomy and physics, which focuses on functional ways of moving. Similarly to rebuilding my saxophone technique, working with Rae demands a high degree of awareness around subtle body positioning.

Contact improvisation is another practice that has greatly informed my work as a musician. It's a free-form, nonhierarchical partnered dance that highlights physical touch and weight sharing. It was inspired by Steve Paxton's work in the 1970s and stems from his piece "Magnesium," where dancers essentially threw themselves at each other and improvised with ways to recover. Since then, contact improvisation has drawn from a variety of dance styles, martial practices, and theater approaches to create a wide-ranging improvised form. At its core, it's a practice of listening intently with the senses, balancing roles of leading and following, and developing a relationship with gravity and momentum. It makes clear many of the dynamics of group improvisation.

Though my work as a contemporary dancer is limited compared to career dancers, the experiences have opened my eyes to topics like phrasing, gesture, and time feel. This viewpoint has shifted my perspective on saxophone playing, making me realize that my body is also my primary instrument. Playing the saxophone relies entirely on my connection to my body, my ability to move my fingers, diaphragm, lips, tongue, and jaw. And it has increased my awareness of how I present myself physically during a performance—how I stand, how I move, and ultimately how these factors impact an audience.

Harrison Argatoff dancing with Adrian Chuquipiondo, Berkan Gorgun, Samantha Johnston, Mika Lior, Suzanne Liska, and Marina Robinson

Lawrence: Valley Voice features established musicians like Michael Davidson and Dan Fortin. How do you balance your role as leader and composer with the collaborative chemistry that clearly drives the quartet?

Harrison: Michael, Dan, and Ian are all such amazing musicians that I could give them hastily scribbled shapes on leftover napkins and they would turn them into rich, nuanced music. My task as a composer is to decide on certain musical restrictions—form, meter, composed material—and then, as a leader, decide how strictly to adhere to them. My process has a puzzle-solving quality: how can I preserve this composition while creating room for the ensemble? During the creative process for Stars, Engines, I became more aware of the benefits of writing efficiently and simply. The simpler I could convey my ideas, the more energy and freedom we felt.

Beyond musicality, I chose to work with them for their humility and professionalism. Even though there's a notable gap in experience between my bandmates and me, they each used their expertise to support my vision. This let me focus, knowing they would hold my awkward moments and misjudgments with patience and grace.

Lawrence: The album title Stars, Engines comes from a story your grandmother told you about waking up at night to look at the stars while hearing vehicles in the valley below. What was it about that particular image that inspired this music?

Harrison: From its inception in 2019, my vision for Valley Voice has been to reflect imagery and stories from my upbringing in British Columbia—two-lane highways winding through narrow valleys, luscious green evergreens and pale dry grasses, shimmering lakes, and family. These are memories I hold very close to my heart.

Back in the fall of 2022, during a time of frantic composition, my grandmother shared a story about waking up in the middle of the night and looking at the stars from her bedroom window while visiting family in the Kootenay region. Having spent much of my childhood in that area, I was reminded of my own fond memories looking up at the clear night sky. This brought me such warm, tender feelings that I wanted to write something to accompany her in that moment, like a lullaby.

As I worked on the piece, I got curious about what sounds had actually accompanied her, and one came forward: engines. In that narrow valley, a small highway provides a constant trickle of vehicle noise as cars, motorcycles, and semi trucks pass through. And so the title was born: Stars, Engines. This beautifully balances the awe of nature, the connection to family, and the mundane realities of everyday life that surround my childhood memories.

Lawrence: These compositions were developed over two years, including time at Banff with mentorship from John Hollenbeck and Sasha Rapoport. Can you walk me through how a piece like "Wishlow" moves from childhood memory to composed music?

Harrison: Though the majority of my composition for this album occurred between 2020 and 2022, some of the pieces actually started to take shape as far back as 2018. With Hollenbeck, I worked on contemporary composition, focusing on exercises in melody, harmony, texture, and rhythm, while also discussing philosophies about composition and music-making in general. Hollenbeck's view that a piece is never 'finished,' but instead remains alive and available for constant editing, is a philosophy that I've embraced wholeheartedly. With Rapoport, I was studying eighteenth-century counterpoint, working on my figured bass, Baroque chord sequences, and writing basic classical forms like minuets, bourrees, and canons. The cherry on top for this creative period was a Banff residency in November 2021, where I shared many of my new Valley Voice compositions for the first time and gained valuable insights from both peers and mentors.

While each piece on Stars, Engines had its own unique composition process, unfortunately for my marketability, my process doesn't usually involve any direct ties between nonmusical inspiration, like memories or images, and the music itself. For me, new compositions typically start from a musical 'seed,' a particular rhythm, tonality, or melody that inspires me to expand on it. Then, after a piece has taken shape, I make connections between it and nonmusical elements in my life, like feelings, memories, places, and/or people. The outlier on this album is the title track, "Stars, Engines," which, as I've shared, was inspired by a story from my grandmother.

"Wishlow," the first track on Stars, Engines, has one of the longer and windier composition stories from the album. Its path began in 2018 as a large ensemble arrangement of Toronto-based folk musician and songwriter Chris Coole's "Baby Blue." My arrangement revolved around a flowing seven-note motif from Coole's original song, using it to bridge between the verses and more contemporary-sounding interludes. A year later, preparing repertoire for Valley Voice's first performance in 2019, I decided to revise my arrangement of "Baby Blue." As I reworked it, I found myself steadily expanding the interlude sections and shrinking Coole's verses. Eventually, all the verses had disappeared, and I was left with a piece of my own.

The new piece's roiling rhythmic sections and floating motifs started to remind me of the flow of a river, and of childhood memories of the Slocan River in BC. As a child, I would float down sections of the river in a rubber inner tube with my family, floating over both calm regions and churning rapids. The most exciting section came right at the end, a two-hundred-meter stretch called the Wishlow rapids. It is a thrilling experience: slowly approaching the white-capped waves, anticipation rising in step with the sounds of crashing water, until finally swooping, swirling, and racing through them.

Lawrence: For the Toronto Streets Tour, you performed in postal codes, requiring listeners to search with open ears. What draws you to these kinds of vulnerable, site-specific presentations?

Harrison: There were a few key elements that drew me to the Toronto Streets Tour project. In 2019, I played thirty consecutive concerts throughout the city, each advertised by postal code and starting time. Beyond the opportunity to hone a set of original solo music through repeated performance, I was curious to hear the music in vastly different physical spaces. From echoing tunnels to traffic-laden roadsides to wide-open beachfront, the music and my performance of it changed drastically day to day. I was also excited by the prospect of sharing my music and the sound of the saxophone with people who may never have heard it otherwise. The project also explored my relationship with, and understanding of, performance itself. I felt questions arising throughout the month, questions like: what does it mean to perform? What's the relationship between audience and performer? What's the impact of a stage or venue? How do I connect with someone through music, through the saxophone? And as I progressed through the city, I started to feel a sense that I was playing not only for the people, but for the city itself: for the hulking concrete buildings, the asphalt underfoot, the wires strung overhead.

It's also worth noting that, as it was my first time planning this type of project, my impulsivity and excitement led me to schedule it in April, which is usually a chilly month here in Toronto. Managing my body temperature became an unexpectedly crucial factor, especially while holding a cold metal tube the entire time.

Lawrence: You've described growing up Doukhobor in rural British Columbia as foundational to your artistic worldview. I'm curious about the tension between individual creative expression and communal music-making traditions. How do you honor that collective heritage?

Harrison: Yes, I grew up in British Columbia's interior and was part of the Doukhobor community that resides there. For anyone who may not know, the Doukhobors are a small group of diasporic Russians who were offered refuge in Canada's western provinces at the turn of the twentieth century. They fled persecution based on their religious beliefs and broader cultural values, which included pacifism, vegetarianism, communal living, and their unique take on Christianity, where they believed that the divine existed inside each of us. As a result, Doukhobor prayer meetings are powerfully simple. Groups gather in unadorned halls to sing together, worshipping the divine by worshipping each other.

The word "Doukhobor" translates to "Spirit Wrestler," a term which speaks to the group's sense of reflectiveness and willingness to debate challenging moral topics. In Robin Wall Kimmerer's book Braiding Sweetgrass, she speaks beautifully to this type of moral wrestling: "If we are fully awake, a moral question arises as we extinguish the other lives around us on behalf of our own. Whether we are digging for wild leeks or going to the mall, how do we consume in a way that does justice to the lives we take? The need to resolve the inescapable tension between honoring life around us and taking it in order to live is part of being human.”

Musically, the Doukhobors have a rich oral singing tradition, prioritizing a cappella singing over the use of other instruments. But, even though I was surrounded by this culture growing up, I didn't actively engage with it, seeing it as more of a family chore.

And so I feel a pang reading your question's phrase "honor that collective heritage." As I've decided to live away from the community in pursuit of studying and playing Western music, I've lost much of my connection to Doukhobor culture. Though I carry with me many of the core values—vegetarianism, belief in community, pacifism—I long to have a deeper connection with the spiritual and cultural practices themselves. I'm hopeful, however, that my efforts to develop a personal voice may, paradoxically, lead me back towards my heritage. I believe that voice will shine brighter the more connected I am to myself and to my past.

Lawrence: Stars, Engines is your first recording as a leader after several collaborative projects. What questions or musical paths are you most curious to explore next?

Harrison: As a leader, I was surprised by how different the creative process felt. In my previous collaborations, I'd grown accustomed to bouncing ideas back and forth, of dialoguing through both cohesion and friction. With Stars, Engines, I instead drew energy from the freedom of leading the project and seeing my artistic vision come to life. But I also felt a heavier quality to the leadership, of needing to plan everything, write everything, and make all the final decisions.

Before I devote myself to new music, I plan to solidify my understanding of how to play the saxophone from a classical perspective. I've been engaged in a wholesale reconstruction of my technique since 2020, and I plan to continue this work until I reach technical stability. But when I do move on, I hope to continue composing with Valley Voice while deepening the group's cohesion. I'd also like to expand on a duo project with guitarist Ian McGimpsey, with whom I created the album Ontario 559 West back in 2020. Since then, McGimpsey has become an extraordinary pedal steel guitarist, and I'm curious to create new pieces that explore the uncommon meeting of our two instruments. I'm also excited to continue developing my skills as a straight-ahead jazz musician. My love for the genre remains strong, as does the equal parts awe and desire to dance I feel listening to Sonny Rollins's classic album A Night at the Village Vanguard.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments