Hunter S. Thompson remains one of America's most mythologized writers, celebrated for his wild persona and Gonzo journalism style that made him a counterculture icon. For decades, readers and critics have focused almost exclusively on his drug-fueled adventures and rebellious image, treating works like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas as touchstones of 1960s rebellion. This narrow view has obscured a more complex truth about Thompson's career and literary legacy.

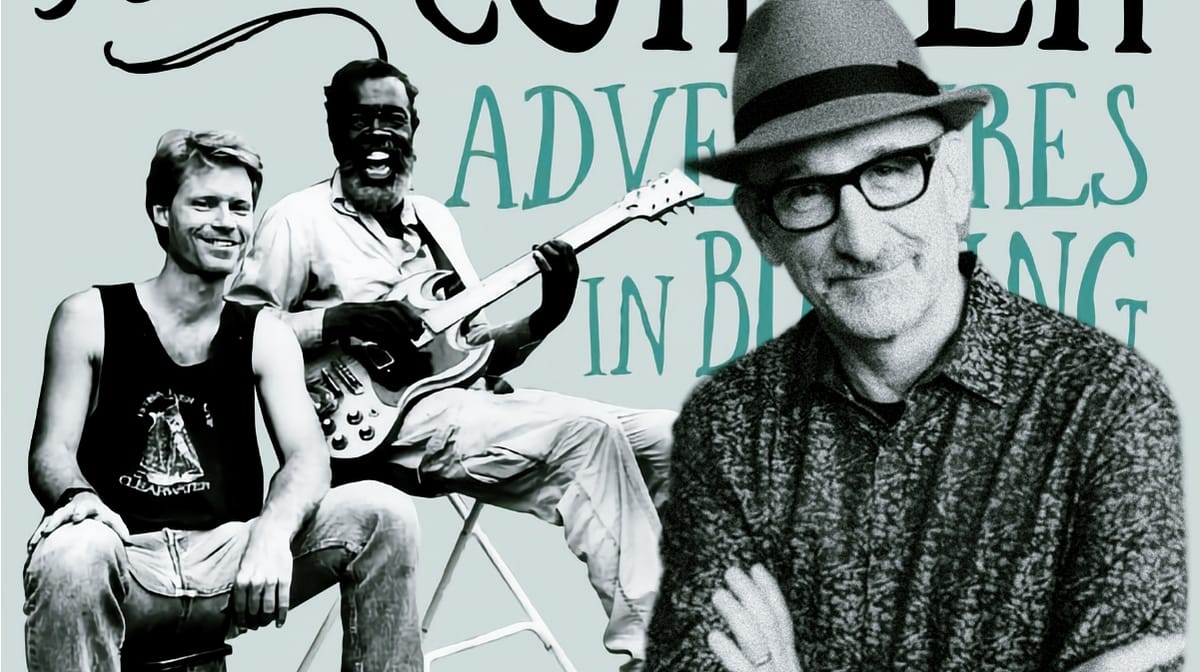

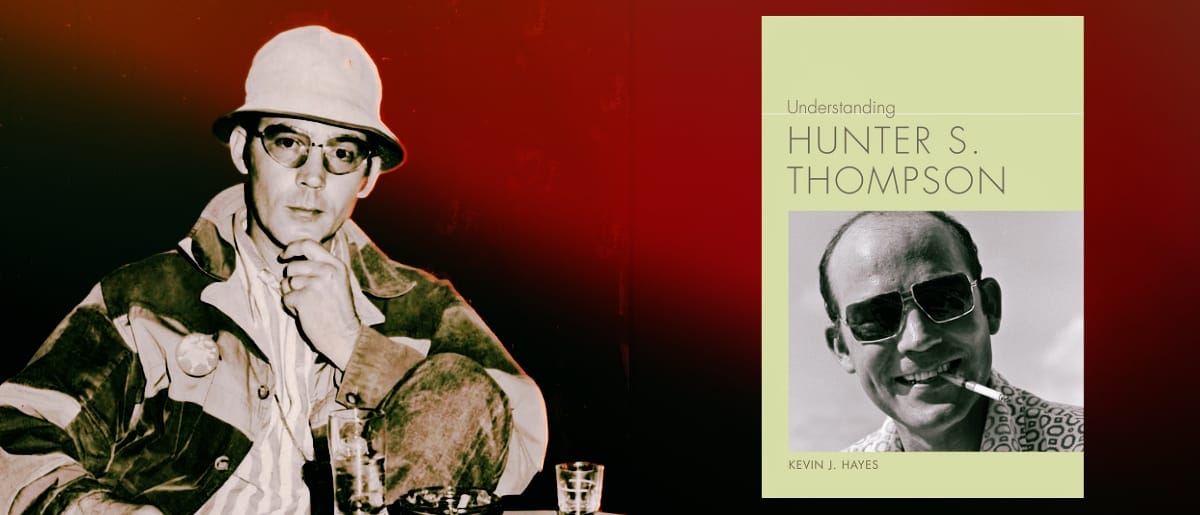

Kevin J. Hayes, author of Understanding Hunter S. Thompson, brings a different perspective to the legend. Hayes argues that Thompson's reputation has been built on a foundation that ignores both his genuine early talent and his profound professional failures. Rather than another celebration of Thompson's outlaw mystique, Hayes offers an unflinching examination of a writer who possessed real gifts but squandered them through self-indulgence and lack of discipline.

Hayes's analysis reveals uncomfortable truths that fans have long overlooked or excused. Thompson's peak creative period lasted roughly four years, from 1970 to 1974, after which he largely coasted on his reputation while missing major assignments and producing increasingly mediocre work. This reassessment forces readers to confront the gap between Thompson's legend and his actual literary output, challenging the romantic narrative that has surrounded him for fifty years.

Lawrence Peryer: Tell me a little bit about your journey to Hunter Thompson, both personally and as a subject for analysis.

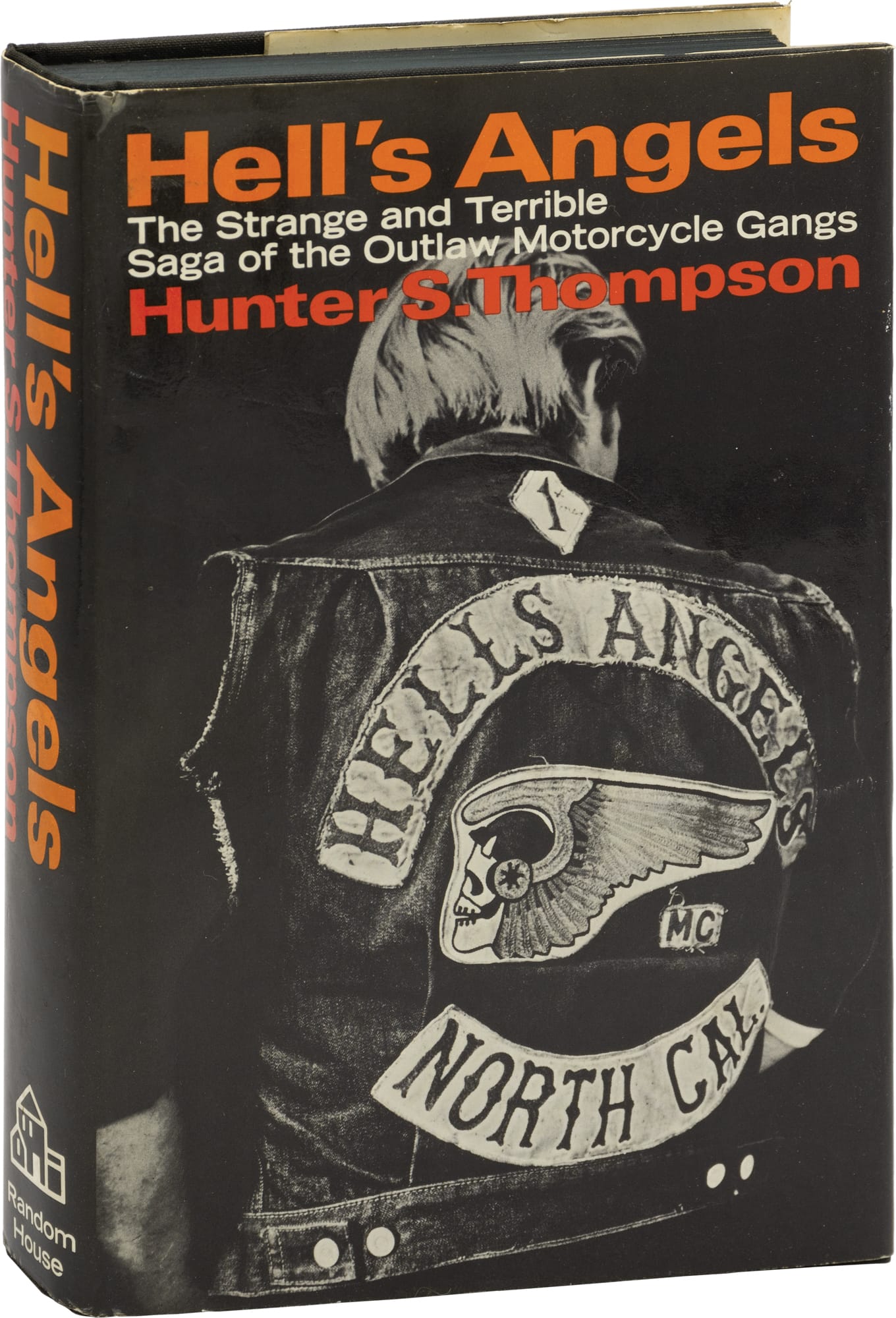

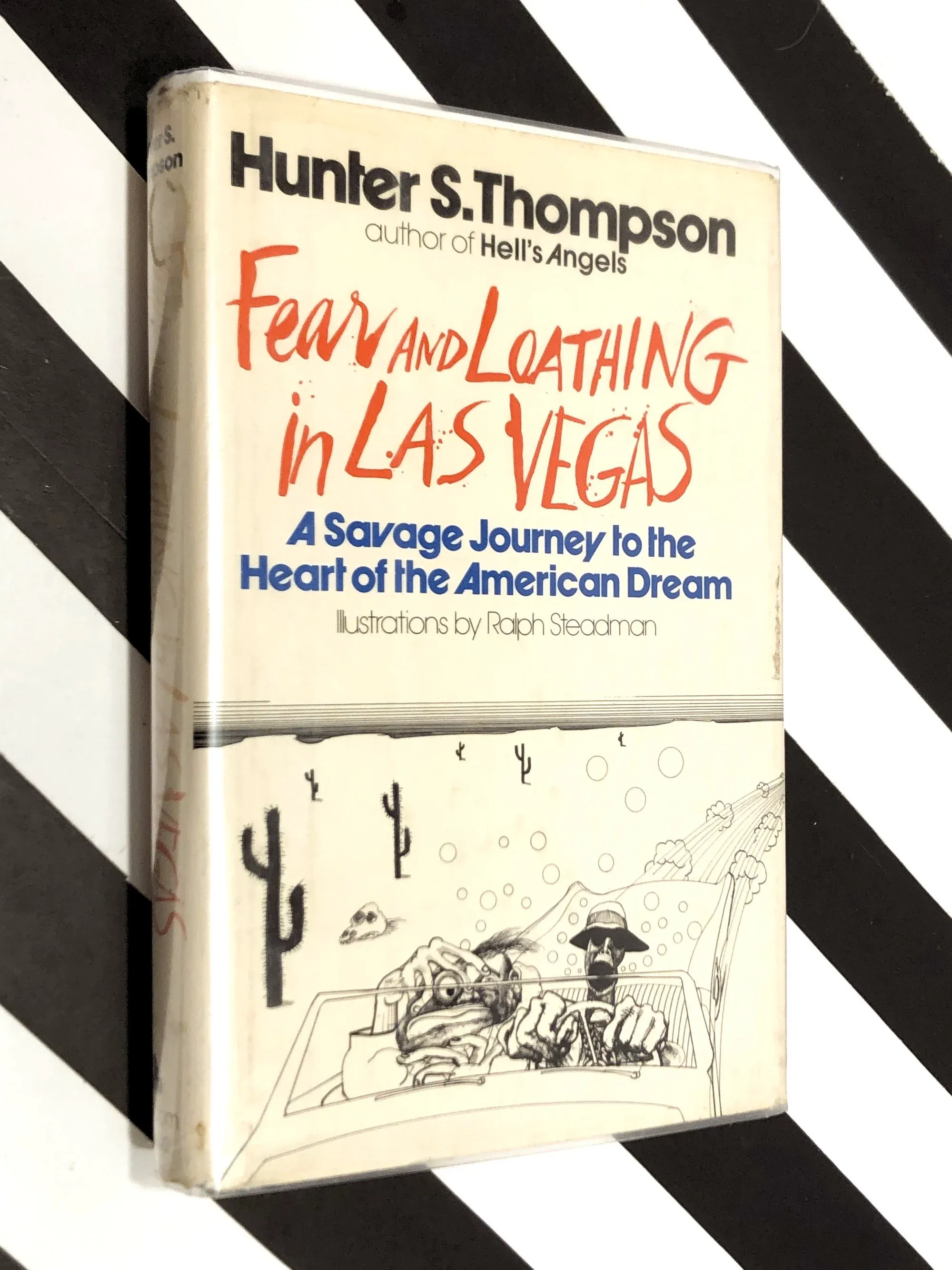

Kevin J. Hayes: I read Hunter Thompson before I ever went to graduate school and got my PhD in English. I first read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in probably the late seventies and just loved it. I thought it was a comic masterpiece. I didn't read anything more of his until later, when I was bicycle touring through Tasmania. I found a copy of his Hell's Angels in a youth hostel, in a take-a-book, leave-a-book shelf.

I took the book and read it, and I enjoyed it, perhaps even more than Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, because it wasn't as funny as that book, but it was much more substantive, I thought. Both of those works impressed me and made me realize that this is a writer who's something special.

I just didn't think much more about them when I went to graduate school. My specialty was early American literature. But something that I put in my book is Thompson's connections with other figures from the South. I make references to Captain John Smith up to Mark Twain and identify links between Thompson and those other writers.

Lawrence: He saw himself in that lineage, too, right? Certainly more than, say, a postmodernist.

Kevin: Yes, I think so. He saw himself as a traditional Southern gentleman and even spoke with a Southern accent. He was born in Kentucky, after all, as I say in my opening sentence. There was a recent book that tried to identify Thompson as a California writer. I appreciated the argument, but I think he still identified more with the South than any other region of the country.

Lawrence: When you look at him in his totality, I don't think you would call him a California writer. I think something that bears mentioning at the outset is the clear-eyed view you take towards him and the contemporary or modern perspective you bring to looking at him. Much like you, I came to him early in life. His work, for many people, was a coming-of-age experience or a rite of passage. The Fear and Loathing work, Hell's Angels, and some of the collections—those were things that fascinated me as a teenager and young adult interested in counterculture and the pirates of our pop culture.

But you force a reexamination, or even more pointedly, to confront and admit to some of the uncomfortable truths about him that were always there but were, for lack of a better way to put it, tolerated, inappropriate, and not something we should celebrate. As a reader, I appreciated your ability to speak about his carelessness with his gift without diminishing what he did accomplish.

Kevin: Like I said, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Hell's Angels both convinced me that he was a special writer. I liked both of those books well enough to propose the project to the press. But I hadn't read much else from him. I had in my home library two of the collections, The Great Shark Hunt and another one that he calls The Gonzo Papers. I had never made it through them because they were anthologies and collections of short pieces, and they had not been able to hold my attention as well as the more unified books.

One thing I decided early on was that I would take a different approach from most of the other books about Thompson. Most of them say, "Okay, he's this Gonzo journalist, and anything that's not Gonzo journalism is not worth looking at." And I thought, "Let's take a different approach. Let's look at some of his other things and see what else he did besides Gonzo journalism or before Gonzo journalism."

One of my most pleasant surprises was reading all the articles he wrote in South America. He traveled all over South America on an adventurous and ambitious journey, writing some wonderful pieces. He did include some of those in The Great Shark Hunt, but not many of them. Most of these haven’t been read or have been read by only a few people since then. I found them to be just wonderful. This is all pre-Gonzo time. It’s very good and entertaining journalism, and I think these are some of his most neglected works, which should be studied.

Lawrence: What were you thinking you were going to set out to do, and did it differ at all from where the process led you?

Kevin: I looked forward to reading some of the Gonzo papers and other works of his that I hadn't studied. I was looking forward to reading the entirety of his works. It turned out to be something of a disappointment because, after Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, I think he just went downhill. He possessed a great natural talent, but he never fully realized or utilized it.

After he established his reputation with Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, he just pretty much skated on his reputation and did awful things. He had an assignment to meet Annie Leibovitz in the Rose Garden for Nixon’s departure from the White House in August 1974. Annie Leibovitz was there with her camera, and Thompson was back at the hotel in the pool watching it on a portable television. It's just so sad. He had a chance to be an eyewitness to history, but he just didn’t feel like it that day and stayed in the pool, relaxing.

Other things too. He went to Vietnam at the end of the war, but he didn’t like it very much. So, he went to Hong Kong, where he missed the fall of Saigon because he was getting his head together. This happens time and time again. He just blows these assignments, these wonderful, well-paying assignments. Rolling Stone was willing to pay him anything to go anywhere. He just blew one assignment after another.

Lawrence: How did analyzing him as a writer and his techniques differ from how you might approach other literary figures? I assume that whenever you're going to look at a new subject, whether it's literary or historical, you're learning a bit about them as a person, as well as how they operate and move through the world. I'm curious about how Thompson may have differed from other subjects you've looked at.

Kevin: Actually, there are some similarities. My primary specialty is early American literature. In the seventeenth, eighteenth centuries, the novel hadn't emerged as a genre. Other literary genres, such as histories and travel narratives, were much more widely respected. Writers in the eighteenth century often incorporated small fictional elements into their travel narratives. Understanding the blend of fiction and nonfiction has been a part of American literature since its inception. I was prepared for studying something that shades into nonfiction, that shades into fiction.

Whereas other people who've looked at Thompson don't have that background, and they see novels as the consummate form of literature. Then they have a hard time fitting Thompson into that genre. People would continually ask him, "Is Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas a novel?" He just always bristled at that question and refused to try and categorize or classify the book.

Lawrence: Outside of what you talked about in his early correspondent days, were there any other personae that revealed surprises to you? Or were there gems that you uncovered that unlocked understanding about him for you?

Kevin: One thing I enjoyed was his letters, or at least the early letters, the first volume of the letters. He was trying out ideas in his private writing before experimenting with them in his public writing. If you compare the South American journalistic writings and the personal letters he was writing at the same time, the personal letters are much freer, much more experimental, much more humorous, and you can see him doing things with his correspondent friends that he wasn't willing to do in his public writings, yet. When he truly had his breakthrough, with the writing of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, is when he recognized how to blend his personal, private voice with his public voice.

Lawrence: What was the impetus for him to allow that breakthrough?

Kevin: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is a rarity in his career because it's one of the few things that he was able to write without being motivated or being pushed by an editor or a publisher to get it done. It's a rare thing that he was able to write on his own, and I think he wrote it as a kind of release valve. For many years, he had been working on a project that his editor, Jim Silverman, had suggested, a book on the American Dream. You read his correspondence, and he just gets angrier and angrier about that American Dream book, that miserable American Dream book that will never end. I think that he wrote Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas to just take a break from the American Dream Book, which he never did write, unless of course you say that Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is his American Dream book, which I think it is.

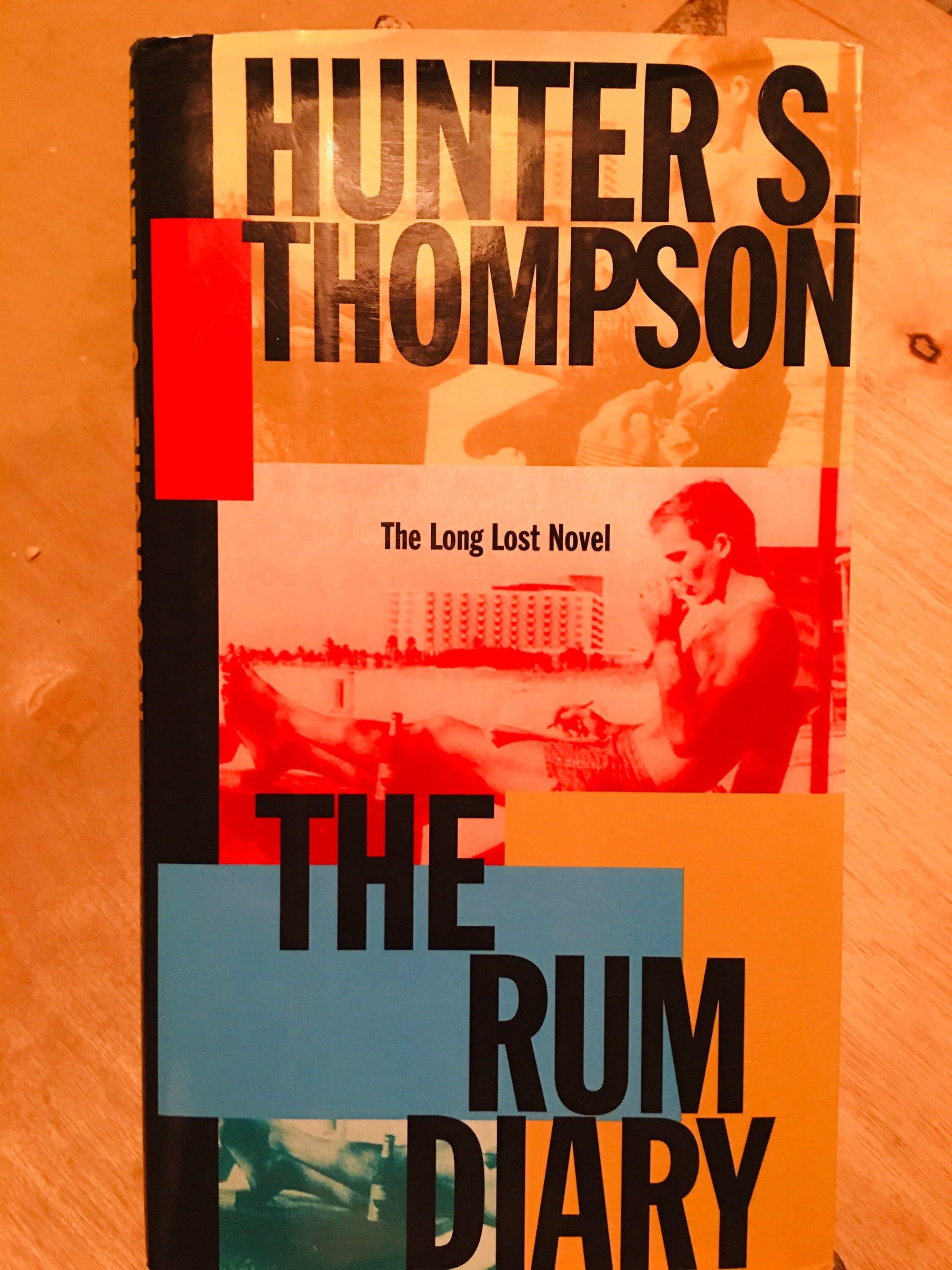

Lawrence: The American Dream book went from being something exciting to him to being this albatross. Can you talk a little bit about that project as well as The Rum Diary? What was it about both of those things that vexed him?

Kevin: He saw the American Dream Book as something akin to the Hell's Angels book: a kind of exposé or social commentary. It was too unfocused. It was going all over the place, and he tried to do research for it. If you look at his correspondence, he has a whole list of magazines that he was reading and subscribing to, to gather all the comments and latest interpretations of the American Dream. But that wasn't his style of working. He was trying to do something that he wasn't particularly suited for. He was fascinated with American culture and the concept of the American dream, but being fascinated with it and being able to pull it together as a tightly focused book are two different things. If he were my student in my freshman comp class, I would say, "Okay, you need a thesis here. You need some focus." He was never able to give it that.

Lawrence: What about The Rum Diary? That's one that pretty much parallels his adult life.

Kevin: I would have liked to see someone edit the whole thing, as it apparently grew to over a thousand pages at its largest point. People kept telling him to trim it down and give it some more focus. It's strange, too, because he always saw the ideal length of a novel as the same length as The Great Gatsby. But for some reason, he couldn't stop expanding The Rum Diary. When it was published, he was not the one who cut it down. His publishers and his editors were the ones who edited the whole thing for him. It's very much a commercial product rather than a literary work as far as I'm concerned.

Lawrence: Outside of his laziness and substance abuse, what was he wrestling with that kept him from doing his work? Why couldn't he wrangle it?

Kevin: I think it reached the point that he just didn't have the discipline to do it anymore. Even as we talk about the discipline, consider how much damage was done to his brain. From the time he was fourteen until the end of his life, he drank every day, all night. If he was awake, he was drinking. You just can't do that without having consequences.

If you look at some of his last writings, like the ones he did for ESPN, the editors say they could hardly use any of his work. They had to give him hints and prompts, and he gave a few sentences here and there that they had to stitch together. It's sad to see that he couldn't even put a thousand words together in the end. Rolling Stone offered him ten thousand dollars for a fifteen-hundred-word column. I've never heard of any freelancer who’s made that kind of money, ten thousand dollars for fifteen hundred words, but he couldn't even get fifteen hundred words together.

He inspired many people to aspire to be journalists like him and emulate the Gonzo style, but the key difference between New Journalism and Gonzo journalism is that there is only one Gonzo journalist. We talk about it as a school of journalism, but there's only one person who has ever done it, and anyone who tries to do it is just a wannabe and can’t be like Hunter Thompson. There's only one Hunter Thompson.

Lawrence: Can you elaborate on that a little bit and tell me the differences between New Journalism and Gonzo journalism?

Kevin: Gonzo journalism is a subset of New Journalism. But one of the key aspects of New Journalism was that you had to immerse yourself in it and spend a considerable amount of time with your subjects, just as Tom Wolfe did with Ken Kesey's Magic Bus. Tom Wolfe became a part of that scene, but he was always the journalist. Tom Wolfe never started using all kinds of drugs and becoming like his subjects, whereas Thompson gradually shaded into that, immersing himself fully in what he was writing about. Certain things, like taking drugs and reporting about taking drugs while you're on the campaign trail, became a part of Gonzo journalism. So he becomes the subject more so than the New Journalists, who are still reporting on something outside themselves.

Lawrence: So it's the complete dissolution of the distinction between subjective and objective.

Kevin: Yeah.

Lawrence: You don't fetishize or give extra real estate to the ’70 to ’74 years. They're upon us in the book, and then they're gone. As a device, it effectively illustrates to the reader just how fleeting his moments of peak lucidity and creative power were.

Kevin: What I didn't want to do was write a biography. However, it's still structured in a rough, chronological way, and I organized it by the different types of hats he wore as a writer. Like I said, in other books about Thompson, they've concentrated almost exclusively on Thompson as a Gonzo journalist. So they highlight the early years. When I got to Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, then we get to the Gonzo papers. It was four volumes in a row that he did, and he grouped them all under the Gonzo papers. To me, when he came up with that label, that was a sign that he wasn't going to change anymore. He wasn't going to try anything different. He had the natural talent to. He could have said, "Okay, Gonzo's played out. I'm going to come up with something different." I just wish that he would've, but he never did.

Lawrence: It's hard not to engage in armchair psychology with him or to think about the roads not taken in his career. What if he had cleaned up and still decided to be a Gonzo journalist, to be just as committed to that immersion in worlds? There are so many different ways an evolution of Hunter Thompson could have played out. Have you ever given much thought to that?

Kevin: As you were talking, what it made me think of is John Cleese. You watch Fawlty Towers and it's so funny, but then there's a lot of anger underneath the characters. Then, later on, I remember seeing something about John Cleese, and he had been to see a therapist, and he was all mellow and he wasn't funny anymore. So, here we have John Cleese, who has worked out his anger issues, but then what he lost was his humor. I'm not sure if a clean Thompson would still be a Gonzo journalist. I guess another comparison would be the chubby comedian. He says, "I can't lose weight because it's part of my persona." Maybe you could lose fifty pounds and still play the chubby comedian. Perhaps if you just didn't drink all day or didn't do all those drugs, you could still play the Gonzo journalist, but he was committed. Once he decided he was going to be a burned-out, drugged-out guy, he did it all day, every day.

Lawrence: Yeah, the closest analog I could think of is probably the most obvious one, which is Keith Richards. Keith Richards has aged in a way that he doesn't strike anyone as somebody who is compromised in who he is. But he didn't take that same path. Not to have an eighty-some-odd-year-old Hunter Thompson and his voice in the world today—that to me is a big loss.

Kevin: Yeah. We need them now more than ever.

Lawrence: A big theme in Thompson's career is this idea that he didn't have that much control over his output. Could you talk a little bit about the people around him that were attempting to keep him going, whether it was because they wanted to keep him relevant, keep the money coming in, or were trying to help him?

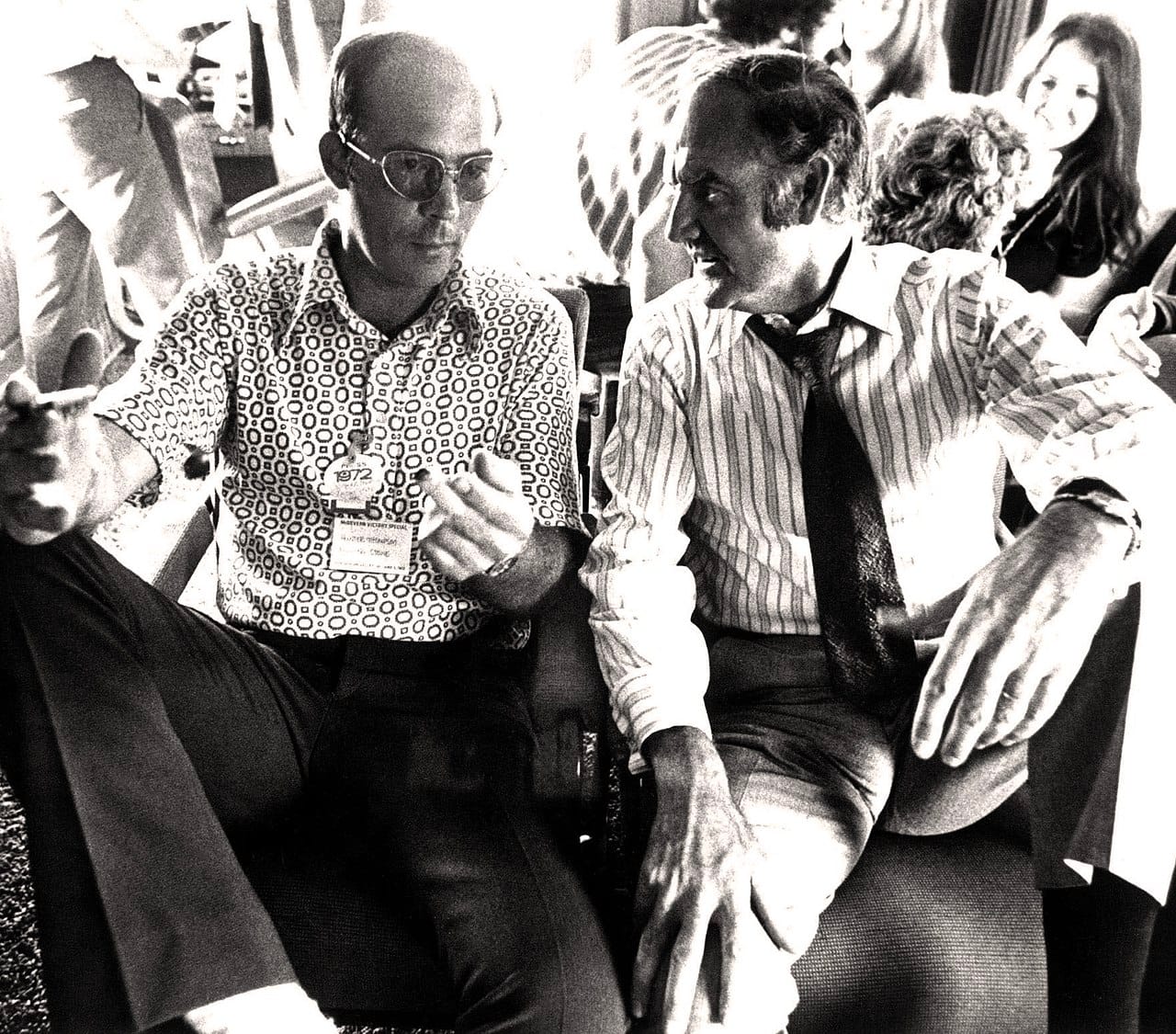

Kevin: He would've written much less than he did if he didn't have these other people around him. He had great fortune when he started writing for Rolling Stone, as Jann Wenner recognized Thompson’s talent and knew how to utilize it to his advantage. His Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail articles, when they appeared in Rolling Stone, really helped to make Rolling Stone and solidify it as not just a rock and roll newspaper, but a serious news journal.

Later, when he wrote a series of articles for the San Francisco Examiner, the Examiner assigned a full-time person to oversee his work and make sure it got completed. I don't think that those are part of the Gonzo papers and are not very good as far as I'm concerned. We just see him repeating the same words and phrases over and over again, without really coming up with anything new. But he was at least coming up with things in a timely fashion because he had this full-time assistant the Examiner paid for. For some reason, he also managed to attract all these young college journalism majors, and they fell in love with him, willing to bend over backwards to help him out.

A lot of his later books were assembled mainly by these helpers who would write down what he said, type it up, and put it in the book. His last couple of books were constructed like that. It was his assistants and later, his assistant, who became his last wife, who assembled those books.

Lawrence: When you talk about his work with the Examiner, that leads me to believe that they knew having the name on the masthead meant something commercially. Why else would you dedicate those resources, not just to overpaying the writer, but to paying the support staff around him? That is the power of his name brand, to say that Hunter Thompson's writing for the San Francisco Examiner. Did it really help them?

Kevin: I think so. I'm going to repeat just what you said. They sure dedicated a lot of resources to it. When you're paying a full-time journalist just to be a helper, that journalist could have written perfectly competent weekly columns himself. But he wouldn't have been Hunter S. Thompson. Maybe he did write some of those columns. I suspect that Hunter S. Thompson may not have written all those Examiner columns. Then perhaps the helper wrote parts of them. I think that his name brand was of immeasurable value to these publications. To go back to my earlier example, why would Rolling Stone be willing to pay ten thousand dollars for a fifteen-hundred-word article?

Lawrence: Do you feel like Thompson is still read? What do you see with students?

Kevin: I think he still has a cult following. If you look at the sales figures on Amazon, his Fear and Loathing and Hell's Angels are still steady sellers and a lot better than any of my books. People are still reading him and buying his books, and I think he still functions as a rite of passage for many young men in their late teens and early twenties. He still has considerable appeal.

We're always drawn to the guy who goes against society, who does what he wants and when he wants, and says to hell with everyone else. That's a kind of a universal archetype, I think.

Lawrence: Now you're associated with him. You're in print with Hunter S. Thompson, part of the legacy. How do you feel about that?

Kevin: I feel fine. I mentioned Thompson in a couple of other books. I wrote a brief history of American literature called A Journey through American Literature, and I used him as part of the introduction to that book. I also wrote a brief biography of Benjamin Franklin a couple of years ago, and I mentioned him in that book as well. In fact, in my opening chapter, I mentioned Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream. That's the subtitle of the ‘Fear and Loathing’ book. My final sentence in the book is, "Benjamin Franklin is the heart of the American Dream." So, I tie together Thompson and Franklin in that book.

Lawrence: Of all the subjects and figures you've written about, Thompson included, which ones do you find yourself coming back to the most, whether as inspirations or as people that you can't shake?

Kevin: Melville. He's still number one in my book.

Lawrence: What accounts for that?

Kevin: Got another hour? (laughter)

Understanding Hunter S. Thompson is available now from USC Press, Bookshop, Powell's, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon.

Check out more like this:

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

The TonearmLawrence Peryer

Comments